Jessica Laser in The Paris Review:

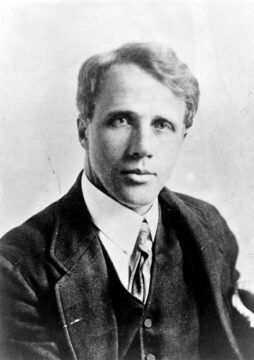

Though he is most often associated with New England, Robert Frost (1874–1963) was born in San Francisco. He dropped out of both Dartmouth and Harvard, taught school like his mother did before him, and became a farmer, the sleeping-in kind, since he wrote at night. He didn’t publish a book of poems until he was thirty-nine, but went on to win four Pulitzers. By the end of his life, he could fill a stadium for a reading. Frost is still well known, occasionally even beloved, but is significantly more known than he is read. When he is included in a university poetry course, it is often as an example of the conservative poetics from which his more provocative, difficult modernist contemporaries (T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound) sought to depart. A few years ago, I set out to write a dissertation on Frost, hoping that sustained focus on his work might allow me to discover a critical language for talking about accessible poems, the kind anybody could read. My research kept turning up interpretations of Frost’s poems that were smart, even beautiful, but were missing something. It was not until I found the journalist Adam Plunkett’s work that I was able to see what that was. “We misunderstand him,” Plunkett wrote of Frost in a 2014 piece for The New Republic, “when, in studying him, we disregard our unstudied reactions.”

Though he is most often associated with New England, Robert Frost (1874–1963) was born in San Francisco. He dropped out of both Dartmouth and Harvard, taught school like his mother did before him, and became a farmer, the sleeping-in kind, since he wrote at night. He didn’t publish a book of poems until he was thirty-nine, but went on to win four Pulitzers. By the end of his life, he could fill a stadium for a reading. Frost is still well known, occasionally even beloved, but is significantly more known than he is read. When he is included in a university poetry course, it is often as an example of the conservative poetics from which his more provocative, difficult modernist contemporaries (T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound) sought to depart. A few years ago, I set out to write a dissertation on Frost, hoping that sustained focus on his work might allow me to discover a critical language for talking about accessible poems, the kind anybody could read. My research kept turning up interpretations of Frost’s poems that were smart, even beautiful, but were missing something. It was not until I found the journalist Adam Plunkett’s work that I was able to see what that was. “We misunderstand him,” Plunkett wrote of Frost in a 2014 piece for The New Republic, “when, in studying him, we disregard our unstudied reactions.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

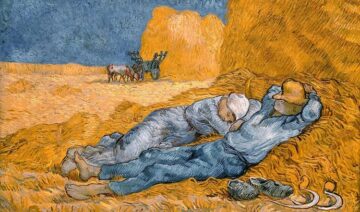

The Russian novelist Ivan Goncharov once said of writers, “And to write and write, like a wheel or a machine, tomorrow, the day after, on holidays; summer will come—and he must still be writing. When is he to stop and rest? Unfortunate man?” Goncharov was born in 1812 and died in 1891, so I am clearly not the model for the writer he was talking about—even though, my prolificacy having often been commented upon, I could otherwise well be. The eponymous hero of his novel Oblomov feels the same way about another character in the book who loves travel, and a second one who enjoys a lively social life, and a third who works hard in the hope of promotion. All of them are viewed by Oblomov as absurdly out of synch with life’s real purpose. This purpose, as Oblomov sees it, is to lie abed doing nothing all the days of one’s life. If rest may be said to have a champion, it is Oblomov, a gentleman by birth for whom “life was divided, in his opinion, into two halves: one consisted of work and boredom—these words were for him synonymous—the other of rest and peaceful good-humor.” Rest, unrelenting rest, is the name of Oblomov’s game.

The Russian novelist Ivan Goncharov once said of writers, “And to write and write, like a wheel or a machine, tomorrow, the day after, on holidays; summer will come—and he must still be writing. When is he to stop and rest? Unfortunate man?” Goncharov was born in 1812 and died in 1891, so I am clearly not the model for the writer he was talking about—even though, my prolificacy having often been commented upon, I could otherwise well be. The eponymous hero of his novel Oblomov feels the same way about another character in the book who loves travel, and a second one who enjoys a lively social life, and a third who works hard in the hope of promotion. All of them are viewed by Oblomov as absurdly out of synch with life’s real purpose. This purpose, as Oblomov sees it, is to lie abed doing nothing all the days of one’s life. If rest may be said to have a champion, it is Oblomov, a gentleman by birth for whom “life was divided, in his opinion, into two halves: one consisted of work and boredom—these words were for him synonymous—the other of rest and peaceful good-humor.” Rest, unrelenting rest, is the name of Oblomov’s game. On February 18, in his inaugural

On February 18, in his inaugural  Consider a pencil lying on your desk. Try to spin it around so that it points once in every direction, but make sure it sweeps over as little of the desk’s surface as possible. You might twirl the pencil about its middle, tracing out a circle. But if you slide it in clever ways, you can do much better.

Consider a pencil lying on your desk. Try to spin it around so that it points once in every direction, but make sure it sweeps over as little of the desk’s surface as possible. You might twirl the pencil about its middle, tracing out a circle. But if you slide it in clever ways, you can do much better. Early one morning in the pit of his fifty-eighth winter — having won a Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Award, and a $10,000 grant from the newly founded National Endowment for the Arts, having dined with the President at the White House, having nurtured the dreams of a generation of poets as a teacher and mentor and unabashed lavisher with praise, and having finally quit drinking — John Berryman jumped from the Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis to his death, slain by the meaning confluence of biochemistry and trauma that can leave even the strongest of minds “so undone.”

Early one morning in the pit of his fifty-eighth winter — having won a Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Award, and a $10,000 grant from the newly founded National Endowment for the Arts, having dined with the President at the White House, having nurtured the dreams of a generation of poets as a teacher and mentor and unabashed lavisher with praise, and having finally quit drinking — John Berryman jumped from the Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis to his death, slain by the meaning confluence of biochemistry and trauma that can leave even the strongest of minds “so undone.” This is a highly readable biography of the Berlin architect who founded the Bauhaus in Germany in the 1920s, by a British design historian. The Bauhaus was arguably the most significant innovation in design education since the Renaissance, as it replaced the then-standard imitation of classical and other historical forms in architecture with the now universal idea that design should be based on function and the economical provision of everyday needs. Although often considered dangerously radical in Germany in the 1920s, after World War II, Bauhaus design approaches spread widely, until they again began to be questioned by postmodernists in the 1970s. By the 1980s, architectural tastes had begun to shift toward an expensive neo-traditionalism. This biography does not address the low opinion many had of Gropius in that era, and it probably will not change some widespread perceptions of Gropius and modern architecture that have taken hold since his death in 1969. It does offer a readable and largely sympathetic account of the complicated personal history of this centrally important modern design educator and mentor.

This is a highly readable biography of the Berlin architect who founded the Bauhaus in Germany in the 1920s, by a British design historian. The Bauhaus was arguably the most significant innovation in design education since the Renaissance, as it replaced the then-standard imitation of classical and other historical forms in architecture with the now universal idea that design should be based on function and the economical provision of everyday needs. Although often considered dangerously radical in Germany in the 1920s, after World War II, Bauhaus design approaches spread widely, until they again began to be questioned by postmodernists in the 1970s. By the 1980s, architectural tastes had begun to shift toward an expensive neo-traditionalism. This biography does not address the low opinion many had of Gropius in that era, and it probably will not change some widespread perceptions of Gropius and modern architecture that have taken hold since his death in 1969. It does offer a readable and largely sympathetic account of the complicated personal history of this centrally important modern design educator and mentor. Sly and the Family Stone achieved unprecedented success in the late Sixties, with number one records, a star turn at Woodstock, a cover on Rolling Stone magazine. Sly was not just a musical genius but a progressive mastermind, insisting that the band be multi-racial and made up of both men and women. Everything about them embodied the notion of inclusivity, of reaching towards a better world in which – without wanting to sound too blandly idealistic – all people could get along together. In a song like “Everyday People”, he made the impossible sound easy.

Sly and the Family Stone achieved unprecedented success in the late Sixties, with number one records, a star turn at Woodstock, a cover on Rolling Stone magazine. Sly was not just a musical genius but a progressive mastermind, insisting that the band be multi-racial and made up of both men and women. Everything about them embodied the notion of inclusivity, of reaching towards a better world in which – without wanting to sound too blandly idealistic – all people could get along together. In a song like “Everyday People”, he made the impossible sound easy. It’s a first date. The drink in your hand is mostly ice. You’ve talked about your jobs, your days, your dogs. The conversation lulls, and you can feel the question coming. “So,” the person across the table asks, “what do you do for fun?”

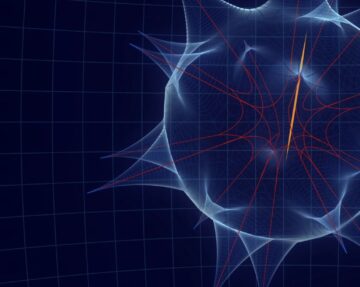

It’s a first date. The drink in your hand is mostly ice. You’ve talked about your jobs, your days, your dogs. The conversation lulls, and you can feel the question coming. “So,” the person across the table asks, “what do you do for fun?” If the world of Severance was real, your “innie” would be reading this article at work, oblivious to the fact that your “outie” intends to spend the evening scouring the internet for these very answers. While the Severance procedure—surgical implantation of a chip into the brain to create separate conscious agents with access to separate streams of memory and experience—is purely fictional at present, another brain-splitting surgical procedure, called a corpus callosotomy, is entirely real and has been in use since the 1940s. Instead of separating work life and personal life, this procedure separates the right and left hemispheres of the brain by severing the major line of communication between them, a thick bundle of nerves called the

If the world of Severance was real, your “innie” would be reading this article at work, oblivious to the fact that your “outie” intends to spend the evening scouring the internet for these very answers. While the Severance procedure—surgical implantation of a chip into the brain to create separate conscious agents with access to separate streams of memory and experience—is purely fictional at present, another brain-splitting surgical procedure, called a corpus callosotomy, is entirely real and has been in use since the 1940s. Instead of separating work life and personal life, this procedure separates the right and left hemispheres of the brain by severing the major line of communication between them, a thick bundle of nerves called the  I had been on my way out for a smoke, and had stopped to hold the heavy bronzed steel and glass door for a woman whose long gray ponytail and colorful mismatched knitwear looked pleasingly hippie-ish.

I had been on my way out for a smoke, and had stopped to hold the heavy bronzed steel and glass door for a woman whose long gray ponytail and colorful mismatched knitwear looked pleasingly hippie-ish. Even chatbots get the blues. According to a

Even chatbots get the blues. According to a

The new study,

The new study,  Wearable devices

Wearable devices