Reed McConnell at Cabinet Magazine:

Wilhelm Rumpf is a naughty boy, and Schoolmaster Heinzerling isn’t having it. When Dr. Heinzerling walks into his classroom one morning to find Rumpf holding forth in an uncanny imitation of his own peculiar manner of address, he sentences him to three days in the school jail, or Karzer. “At the naext stopaid traick I’ll aexpel you!” he tells Rumpf a few hours later while visiting him in his cell. “Pot yourself ain mai place.” Rumpf, convinced that his expulsion is inevitable, takes this last injunction literally, locking Heinzerling in the Karzer and giving orders in Heinzerling’s voice until he decides to strike a deal. Clear my name, he tells Heinzerling, and I’ll never tell anyone that I outwitted you. The deal holds, and no one is the wiser.

Wilhelm Rumpf is a naughty boy, and Schoolmaster Heinzerling isn’t having it. When Dr. Heinzerling walks into his classroom one morning to find Rumpf holding forth in an uncanny imitation of his own peculiar manner of address, he sentences him to three days in the school jail, or Karzer. “At the naext stopaid traick I’ll aexpel you!” he tells Rumpf a few hours later while visiting him in his cell. “Pot yourself ain mai place.” Rumpf, convinced that his expulsion is inevitable, takes this last injunction literally, locking Heinzerling in the Karzer and giving orders in Heinzerling’s voice until he decides to strike a deal. Clear my name, he tells Heinzerling, and I’ll never tell anyone that I outwitted you. The deal holds, and no one is the wiser.

First published in 1872, Ernst Eckstein’s short story “Der Besuch im Carcer” is a classic text in German high school classes and thematizes what was once an equally classic element of German universities and secondary schools. Starting in the sixteenth century, many educational institutions had their own jails, ranging in size from single rooms at boarding schools to entire wings or small buildings at larger universities.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Square foot for square foot, the Frick has the densest concentration of masterpieces in America, installed alongside decorative objects in gloriously stuffy interiors. The art historian Bernard Berenson once sniffed that the Frick, founded by the morally compromised robber-baron philanthropist Henry Clay Frick, was just a “mausoleum.” Not true! Since Frick’s 1919 death, this stupendous museum has added countless gifts and acquisitions. A Watteau entered the collection in 1991. At the entrance is a wild Murillo self-portrait painted on a trompe l’oeil stone block that was added in 2014. At the Frick, we commune with the ages.

Square foot for square foot, the Frick has the densest concentration of masterpieces in America, installed alongside decorative objects in gloriously stuffy interiors. The art historian Bernard Berenson once sniffed that the Frick, founded by the morally compromised robber-baron philanthropist Henry Clay Frick, was just a “mausoleum.” Not true! Since Frick’s 1919 death, this stupendous museum has added countless gifts and acquisitions. A Watteau entered the collection in 1991. At the entrance is a wild Murillo self-portrait painted on a trompe l’oeil stone block that was added in 2014. At the Frick, we commune with the ages. What does it mean for a television show to be cinematic? It certainly doesn’t have to mean that the series in question is about the movie business, though that happens to be the case with The Studio, the new Apple TV+ comedy starring Seth Rogen and co-created by Rogen and his longtime creative partner Evan Goldberg (Superbad, Pineapple Express, Neighbors 2). In the first episode, Rogen’s Matt Remick becomes the new president of the venerable century-old Continental Studios when its previous head, industry legend and Matt’s onetime mentor Patty Leigh (Catherine O’Hara), is forced out of the job. Matt got into the business out of a love for classic cinema—he’s forever dropping references to everything from Goodfellas to Fight Club to I Am Cuba. But the realities of the 21st-century box office mean that his workdays revolve around meetings about acquiring the rights to the Kool-Aid brand name for a franchise that will star Ice Cube as the voice of an animated pitcher of red liquid.

What does it mean for a television show to be cinematic? It certainly doesn’t have to mean that the series in question is about the movie business, though that happens to be the case with The Studio, the new Apple TV+ comedy starring Seth Rogen and co-created by Rogen and his longtime creative partner Evan Goldberg (Superbad, Pineapple Express, Neighbors 2). In the first episode, Rogen’s Matt Remick becomes the new president of the venerable century-old Continental Studios when its previous head, industry legend and Matt’s onetime mentor Patty Leigh (Catherine O’Hara), is forced out of the job. Matt got into the business out of a love for classic cinema—he’s forever dropping references to everything from Goodfellas to Fight Club to I Am Cuba. But the realities of the 21st-century box office mean that his workdays revolve around meetings about acquiring the rights to the Kool-Aid brand name for a franchise that will star Ice Cube as the voice of an animated pitcher of red liquid. I was an English major in college, and my favorite poet was the first-generation Romantic William Wordsworth. For one thing, there’s the name, the best example of

I was an English major in college, and my favorite poet was the first-generation Romantic William Wordsworth. For one thing, there’s the name, the best example of  At the start of the last class, Breyten took a magnum of red wine out of a tote bag and plonked it on the table among our normal-sized bottles. It was a Bordeaux, I like to think. The bottle was hilariously large, as if it had priapism, and he shared it round in paper cups, then went into full-on raconteur mode. He’d been kicking back for at least half an hour and was talking about his cottage in Catalonia, near Girona, when I interjected something about the Barri Gòtic in Barcelona, trying to assert that I also knew a lot about the locale. Breyten’s eyes slid over me. He gave the merest nod and continued his ramifying digression.

At the start of the last class, Breyten took a magnum of red wine out of a tote bag and plonked it on the table among our normal-sized bottles. It was a Bordeaux, I like to think. The bottle was hilariously large, as if it had priapism, and he shared it round in paper cups, then went into full-on raconteur mode. He’d been kicking back for at least half an hour and was talking about his cottage in Catalonia, near Girona, when I interjected something about the Barri Gòtic in Barcelona, trying to assert that I also knew a lot about the locale. Breyten’s eyes slid over me. He gave the merest nod and continued his ramifying digression. The Dream Hotel is Laila Lalami’s fifth novel – earlier works received nominations for the Booker, Pulitzer and National book awards – and has been longlisted for the Women’s prize. Her 2020 nonfiction book, Conditional Citizens, draws on her experiences as a Moroccan American to think about her adopted country’s two-tier system: how rights and freedoms are, in practice, exercised very differently across race, class, gender and national origin. Lalami’s fiction has explored the way these differences play out across a range of times and places: from Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits (2005), on migrant experiences in modern Morocco, to

The Dream Hotel is Laila Lalami’s fifth novel – earlier works received nominations for the Booker, Pulitzer and National book awards – and has been longlisted for the Women’s prize. Her 2020 nonfiction book, Conditional Citizens, draws on her experiences as a Moroccan American to think about her adopted country’s two-tier system: how rights and freedoms are, in practice, exercised very differently across race, class, gender and national origin. Lalami’s fiction has explored the way these differences play out across a range of times and places: from Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits (2005), on migrant experiences in modern Morocco, to  If you watch clips of his last appearance as Ziggy, at his infamous concert at the Hammersmith Odeon, you can see these rapid- fire changes in action. As Bowie starts “Ziggy Stardust,” he’s wearing a black diamond-shaped jumpsuit with shots of blue and red, his feet planted about a meter apart. Two pairs of hands materialize out of the darkness and deftly yank its sleeves, revealing the famously short white satin kimono, which is positively luminescent under the stage lights. He does the same thing again later with two more outfits by Kansai Yamamoto: the white cape revealing the marvelous, multicolored jumpsuit. At one point, Bowie goes offstage to change into his sculpted-shoulder two-piece, another number by Burretti, which he wears with the boots. You can tell how tight it is because he grimaces as it goes up his legs. He smooths out each of his sleeves so that they sit just so. He must have looked something like a red, blue, and silver mirage, a sensory assault on your eyes and ears that made them explode with color and sound. Exhilarating doesn’t even begin to describe it. This was nothing short of earth-shattering.

If you watch clips of his last appearance as Ziggy, at his infamous concert at the Hammersmith Odeon, you can see these rapid- fire changes in action. As Bowie starts “Ziggy Stardust,” he’s wearing a black diamond-shaped jumpsuit with shots of blue and red, his feet planted about a meter apart. Two pairs of hands materialize out of the darkness and deftly yank its sleeves, revealing the famously short white satin kimono, which is positively luminescent under the stage lights. He does the same thing again later with two more outfits by Kansai Yamamoto: the white cape revealing the marvelous, multicolored jumpsuit. At one point, Bowie goes offstage to change into his sculpted-shoulder two-piece, another number by Burretti, which he wears with the boots. You can tell how tight it is because he grimaces as it goes up his legs. He smooths out each of his sleeves so that they sit just so. He must have looked something like a red, blue, and silver mirage, a sensory assault on your eyes and ears that made them explode with color and sound. Exhilarating doesn’t even begin to describe it. This was nothing short of earth-shattering.

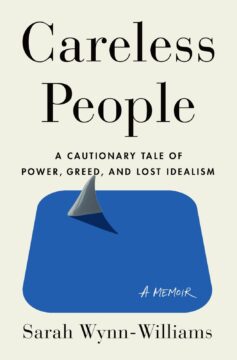

Meta’s governmental strategy and influence is now clearer than ever, thanks to Sarah Wynn Williams’s recently published memoir,

Meta’s governmental strategy and influence is now clearer than ever, thanks to Sarah Wynn Williams’s recently published memoir,  WIRED: In the late ’90s, when the internet began to spread, there was a discourse that this would bring about world peace. It was thought that with more information reaching more people, everyone would know the truth, mutual understanding would be born, and humanity would become wiser. WIRED, which has been a voice of change and hope in the digital age, was part of that thinking at the time. In your new book, Nexus, you write that such a view of information is too naive. Can you explain this?

WIRED: In the late ’90s, when the internet began to spread, there was a discourse that this would bring about world peace. It was thought that with more information reaching more people, everyone would know the truth, mutual understanding would be born, and humanity would become wiser. WIRED, which has been a voice of change and hope in the digital age, was part of that thinking at the time. In your new book, Nexus, you write that such a view of information is too naive. Can you explain this? O

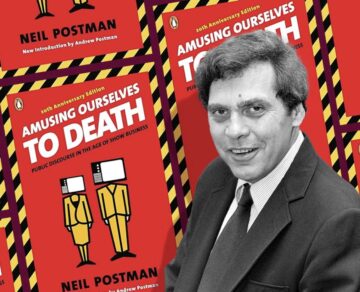

O Every so often an eye-opening work of social criticism becomes a surprise bestseller. In 1979, everyone was talking about Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism, and in 1987, it was Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind. Last year, Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation raised the alarm, encouraging readers outside the parenting-book world to consider what the teenage mental health crisis might mean for the culture at large. Typically the work of a professor with an aptitude for speaking to a general readership, this sort of book hits just as popular anxiety about a new technology or ideology—smartphones, the self-actualization movement, multiculturalism—is cresting. Ideas that may have been simmering away in academia suddenly burst into the common conversation. However, the very qualities that make these books feel tremendously relevant at a particular historical moment also tend to make them fade into obscurity when that moment passes. The blockbuster cultural criticism book tends to speak to its time—then become a curio as the culture changes around it.

Every so often an eye-opening work of social criticism becomes a surprise bestseller. In 1979, everyone was talking about Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism, and in 1987, it was Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind. Last year, Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation raised the alarm, encouraging readers outside the parenting-book world to consider what the teenage mental health crisis might mean for the culture at large. Typically the work of a professor with an aptitude for speaking to a general readership, this sort of book hits just as popular anxiety about a new technology or ideology—smartphones, the self-actualization movement, multiculturalism—is cresting. Ideas that may have been simmering away in academia suddenly burst into the common conversation. However, the very qualities that make these books feel tremendously relevant at a particular historical moment also tend to make them fade into obscurity when that moment passes. The blockbuster cultural criticism book tends to speak to its time—then become a curio as the culture changes around it. In all animals mating is a deal: one sex donates a few million sperm, the other a handful of eggs, the merger between which—unless a predator intervenes—will result in a brood of young. Win-win for the parents, genetically speaking. But there are few creatures that behave as if sex is a dull, simple or even mutually beneficial transaction and many that behave as if it is an event of transcendent emotional and aesthetic salience to be treated with reverence, suspicion, angst and quite a bit of violence.

In all animals mating is a deal: one sex donates a few million sperm, the other a handful of eggs, the merger between which—unless a predator intervenes—will result in a brood of young. Win-win for the parents, genetically speaking. But there are few creatures that behave as if sex is a dull, simple or even mutually beneficial transaction and many that behave as if it is an event of transcendent emotional and aesthetic salience to be treated with reverence, suspicion, angst and quite a bit of violence. With roughly

With roughly