Ben Brubaker in Quanta:

They say a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, but for computer scientists, two birds in a hole are better still. That’s because those cohabiting birds are the protagonists of a deceptively simple mathematical theorem called the pigeonhole principle. It’s easy to sum up in one short sentence: If six pigeons nestle into five pigeonholes, at least two of them must share a hole. That’s it — that’s the whole thing.

They say a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, but for computer scientists, two birds in a hole are better still. That’s because those cohabiting birds are the protagonists of a deceptively simple mathematical theorem called the pigeonhole principle. It’s easy to sum up in one short sentence: If six pigeons nestle into five pigeonholes, at least two of them must share a hole. That’s it — that’s the whole thing.

“The pigeonhole principle is a theorem that elicits a smile,” said Christos Papadimitriou(opens a new tab), a theoretical computer scientist at Columbia University. “It’s a fantastic conversation piece.”

But the pigeonhole principle isn’t just for the birds. Even though it sounds painfully straightforward, it’s become a powerful tool for researchers engaged in the central project of theoretical computer science: mapping the hidden connections between different problems.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Trump administration’s assault on higher education continues to escalate. The White House has

The Trump administration’s assault on higher education continues to escalate. The White House has  What was Emersonian? I first saw the term used in an essay by Harold Bloom called “The New Transcendentalism” about “the visionary strain” in the American poets W. S. Merwin, John Ashbery, and A. R. Ammons. Their excellence as poets (Bloom ranked them 3, 2, 1) depended almost entirely on their Emersonianism. Bloom wrote as if everyone, including the women he omitted, knew what it meant. Now I think he meant unrestrained by conventions of a closed system, like Christianity or the Boy Scouts of America. To be Emersonian was to be true to one’s own system, whatever that might be, idealist, visionary, in any case, a poetry of the sublime and the large statement, the lingua franca of Wallace Stevens, say, but also the kitchen sink realism of William Carlos Williams, though not as wild and visionary as William Blake, or as talented. Could we say existentialist? American poets who dwelt in the Emersonian sunshine might write free verse or in song meters, like Blake. Nevertheless, Emerson’s idealism was both principle and excuse for their poetry, with Whitman and Dickinson as influential figures. Whitman’s muse was installed amid the kitchenware. Dickinson’s lived in her upstairs bedroom. Domesticated but wild, wolves in Victorian sheepskin, these Emersonians were ordained to go uncollared but prophetic, unpenned with fountain pen in hand.

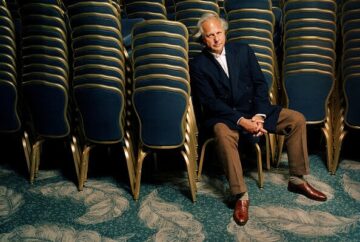

What was Emersonian? I first saw the term used in an essay by Harold Bloom called “The New Transcendentalism” about “the visionary strain” in the American poets W. S. Merwin, John Ashbery, and A. R. Ammons. Their excellence as poets (Bloom ranked them 3, 2, 1) depended almost entirely on their Emersonianism. Bloom wrote as if everyone, including the women he omitted, knew what it meant. Now I think he meant unrestrained by conventions of a closed system, like Christianity or the Boy Scouts of America. To be Emersonian was to be true to one’s own system, whatever that might be, idealist, visionary, in any case, a poetry of the sublime and the large statement, the lingua franca of Wallace Stevens, say, but also the kitchen sink realism of William Carlos Williams, though not as wild and visionary as William Blake, or as talented. Could we say existentialist? American poets who dwelt in the Emersonian sunshine might write free verse or in song meters, like Blake. Nevertheless, Emerson’s idealism was both principle and excuse for their poetry, with Whitman and Dickinson as influential figures. Whitman’s muse was installed amid the kitchenware. Dickinson’s lived in her upstairs bedroom. Domesticated but wild, wolves in Victorian sheepskin, these Emersonians were ordained to go uncollared but prophetic, unpenned with fountain pen in hand. If there’s anyone who knows how to play a wealthy man with a secret, it’s Jon Hamm. From Mad Men‘s Don Draper to Andrew Cooper turning to a life of crime to maintain his lavish lifestyle in his new series Your Friends and Neighbors (

If there’s anyone who knows how to play a wealthy man with a secret, it’s Jon Hamm. From Mad Men‘s Don Draper to Andrew Cooper turning to a life of crime to maintain his lavish lifestyle in his new series Your Friends and Neighbors ( For sheer cushiness

For sheer cushiness The classic liberal society of participatory institutions, competitive markets, and social mobility, which formerly nurtured and sustained the American belief in individual freedom and opportunity along with popular self-rule, is today scarcely a memory. In its place, the corporate organization of society—expanding for 150 years with its encompassing hierarchies and concentrations of power—recast American society and its popular practices and expectations. Amid the unending acceleration of production and technological innovation, omnipresent merchandisers and round-the-clock digital stimulants cajole and persuade individuals to pursue unprecedented enticements: indulgence in limitless appetitive striving and the pseudo-celebrity of ceaseless self-inflation. Facing an ever more constricting social reality and temptations ever less compatible with the core liberal virtues of moderation and self-restraint, Americans may wonder what is still liberal about their axiomatically liberal society. If the answer is cautionary, where does this leave us? And what options do we have?

The classic liberal society of participatory institutions, competitive markets, and social mobility, which formerly nurtured and sustained the American belief in individual freedom and opportunity along with popular self-rule, is today scarcely a memory. In its place, the corporate organization of society—expanding for 150 years with its encompassing hierarchies and concentrations of power—recast American society and its popular practices and expectations. Amid the unending acceleration of production and technological innovation, omnipresent merchandisers and round-the-clock digital stimulants cajole and persuade individuals to pursue unprecedented enticements: indulgence in limitless appetitive striving and the pseudo-celebrity of ceaseless self-inflation. Facing an ever more constricting social reality and temptations ever less compatible with the core liberal virtues of moderation and self-restraint, Americans may wonder what is still liberal about their axiomatically liberal society. If the answer is cautionary, where does this leave us? And what options do we have?

F

F A unique aspect of human developmental systems are our rich, cumulative cultures, which we inherit along with our genes. Thousands of years of gendered cultures, together with our evolved and unparalleled capacity for social learning, might have reduced the need for genes to be the ‘carriers’ of sex-linked behavioural features. Instead, as John Dupré, Daphna Joel and I have

A unique aspect of human developmental systems are our rich, cumulative cultures, which we inherit along with our genes. Thousands of years of gendered cultures, together with our evolved and unparalleled capacity for social learning, might have reduced the need for genes to be the ‘carriers’ of sex-linked behavioural features. Instead, as John Dupré, Daphna Joel and I have  So sharp are partisan divisions these days that it can seem as if people are experiencing entirely different realities. Maybe they actually are, according to Leor Zmigrod, a neuroscientist and political psychologist at Cambridge University. In a new book, “The Ideological Brain: The Radical Science of Flexible Thinking,” Dr. Zmigrod explores the emerging evidence that brain physiology and biology help explain not just why people are prone to ideology but how they perceive and share information.

So sharp are partisan divisions these days that it can seem as if people are experiencing entirely different realities. Maybe they actually are, according to Leor Zmigrod, a neuroscientist and political psychologist at Cambridge University. In a new book, “The Ideological Brain: The Radical Science of Flexible Thinking,” Dr. Zmigrod explores the emerging evidence that brain physiology and biology help explain not just why people are prone to ideology but how they perceive and share information. Among the many grievances aired by Norman Podhoretz in his insufferable 1967 memoir Making It is an already septic grudge concerning The New Yorker’s publication of James Baldwin’s most famous essay in 1962. Titled, following the magazine’s convention, “

Among the many grievances aired by Norman Podhoretz in his insufferable 1967 memoir Making It is an already septic grudge concerning The New Yorker’s publication of James Baldwin’s most famous essay in 1962. Titled, following the magazine’s convention, “ “That Cajun blackened shrimp recipe looks really good,” I tell my husband while scrolling through cooking videos online. The presenter describes it well: juicy, plump, smoky, a parade of spices. Without making the dish, I can only imagine how it tastes. But a new device inches us closer to recreating tastes from the digital world directly in our mouths. Smaller than a stamp, it contains a slurry of chemicals representing primary flavors like salty, sweet, sour, bitter, and savory (or umami). The reusable device mixes these together to mimic the taste of coffee, cake, and other foods and drinks.

“That Cajun blackened shrimp recipe looks really good,” I tell my husband while scrolling through cooking videos online. The presenter describes it well: juicy, plump, smoky, a parade of spices. Without making the dish, I can only imagine how it tastes. But a new device inches us closer to recreating tastes from the digital world directly in our mouths. Smaller than a stamp, it contains a slurry of chemicals representing primary flavors like salty, sweet, sour, bitter, and savory (or umami). The reusable device mixes these together to mimic the taste of coffee, cake, and other foods and drinks. Each balloon carried two copilots vying to prevail in the 1995 Coupe Aéronautique Gordon Bennett, ballooning’s oldest and most prestigious aeronautical race. The goal was to travel the farthest distance possible before landing. Only the world’s most daring and decorated aeronauts could claim a spot in the field. The race typically lasted one or two days, and occasionally stretched into a third. No Gordon Bennett balloon had ever flown a fourth night, but favorable weather and a stretch of newly opened airspace now made that feat attainable for the first time. “It was fabulous, and we knew it,” said Martin Stürzlinger, a member of the ground crew for a balloon called the D-Caribbean.

Each balloon carried two copilots vying to prevail in the 1995 Coupe Aéronautique Gordon Bennett, ballooning’s oldest and most prestigious aeronautical race. The goal was to travel the farthest distance possible before landing. Only the world’s most daring and decorated aeronauts could claim a spot in the field. The race typically lasted one or two days, and occasionally stretched into a third. No Gordon Bennett balloon had ever flown a fourth night, but favorable weather and a stretch of newly opened airspace now made that feat attainable for the first time. “It was fabulous, and we knew it,” said Martin Stürzlinger, a member of the ground crew for a balloon called the D-Caribbean.