Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

The Fourth Transformation

David Adler, Vanessa Romero Rocha, and Michael Galant in Phenomenal World:

On January 12, tens of thousands of Mexican citizens packed into the Zócalo to hear President Claudia Sheinbaum deliver her report on the first 100 days of government. Her announcements reflected an agenda both ambitious in scale and comprehensive in scope: sixteen new laws and twelve constitutional reforms ranging from the recognition of Indigenous peoples and the real increase in the minimum wage, to the recovery of Mexico’s national ownership of natural resources and a crackdown on tax evasion. “Let it be heard loud and clear,” Sheinbaum said. “We will not return to the neoliberal model … We will continue with Mexican Humanism and with the maxim of ‘For the good of all, first the poor.’”

That maxim sits at the heart of the “Fourth Transformation,” the political-economic project inaugurated by Sheinbaum’s predecessor Andrés Manuel López Obrador, or AMLO. Founded during his own campaign for the presidency, AMLO’s National Regeneration Movement (Morena, in its Spanish abbreviation) drew inspiration from the country’s three prior great transformations—the War of Independence (1810–1821), the War of Reform (1857–1861), and the Mexican Revolution (1910–1917). A century on from the Revolution, AMLO claimed to recover its tradition of popular self-determination, proposing “a system of democratic planning of national development” to shape economic growth toward the goals of “independence” and the “political, social, and cultural democratization of the nation.” Sheinbaum now promises to construct a “second storey” atop this political edifice.

The return of “democratic planning” to Mexican governance would mark a sea change in the country’s prevailing political economy.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The New Legislators of Silicon Valley

Evgeny Morozov in The Ideas Letter:

There is a certain disorienting thrill in witnessing, over the past few years, the profusion of bold, often baffling, occasionally horrifying ideas pouring from the ranks of America’s tech elite.

Consider the heresies of Balaji Srinivasan and Peter Thiel, who, in celebrating the “network state” and seasteading have hatched an escape doctrine for digital aristocrats. Where Srinivasan conjures blockchain fiefdoms with à la carte citizenship and pay-per-view police forces, Thiel pines for oceanic platforms where the wealthy might float beyond government reach, their libertarian fantasies bobbing like luxury yachts in international waters.

Elsewhere, Silicon Valley’s solutionist overdose has inflated an ideas bubble that rivals its financial ones—a frothy marketplace where grand narratives appreciate faster than stock options. Thus, Sam Altman casually drafts planetary blueprints for AI (non-)regulation and even AI welfare (“capitalism for everyone!”), while crypto acolytes (Marc Andreessen, David Sacks), aspiring celestial colonizers (Musk, Bezos), and nuclear revivalists (Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Altman) offer their own grandiose, exciting solutions to problems of seemingly unknown origin. (Who’s guzzling up all this energy we suddenly need so badly? A true mystery, this.)

But more mundane subjects, from foreign policy to defense, increasingly preoccupy them too. Eric Schmidt—a man whose personality could be mistaken for a blank Google Doc—has not only penned two books with Henry Kissinger but also regularly contributes to Foreign Affairs and other such factories of doom and dogma. And he is after big, meaty subjects, the kind that demand somber nods at think-tank luncheons. “Ukraine is losing the drone war” proclaims a piece of his from January 2024. Could this be – a pure coincidence, surely – the same Eric Schmidt, who, just months earlier, launched a drone company?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Gananath Obeyesekere (1930 – 2025) Anthropologist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

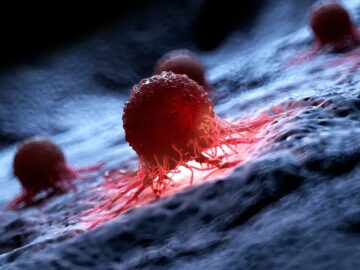

How Do Cancer Cells Migrate to New Tissues and Take Hold?

Amber Dance in Smithsonian:

Back in 2014, a woman with advanced cancer pushed Adrienne Boire’s scientific life in a whole new direction. The cancer, which had begun in the breast, had found its way into the patient’s spinal fluid, rendering the middle-aged mother of two unable to walk. “When did this happen?” she asked from her hospital bed. “Why are the cells growing there?” Why, indeed. Why would cancer cells migrate to the spinal fluid, far from where they’d been birthed, and how did they manage to thrive in a liquid so strikingly poor in nutrients? Boire, a physician-scientist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, decided that those questions deserved answers.

Back in 2014, a woman with advanced cancer pushed Adrienne Boire’s scientific life in a whole new direction. The cancer, which had begun in the breast, had found its way into the patient’s spinal fluid, rendering the middle-aged mother of two unable to walk. “When did this happen?” she asked from her hospital bed. “Why are the cells growing there?” Why, indeed. Why would cancer cells migrate to the spinal fluid, far from where they’d been birthed, and how did they manage to thrive in a liquid so strikingly poor in nutrients? Boire, a physician-scientist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, decided that those questions deserved answers.

The answers are urgent, because the same thing that happened to Boire’s patient is happening to increasing numbers of cancer patients. As the ability to treat initial, or primary, tumors has improved, people survive early rounds with cancer only to come back years or decades later when the cancer has somehow resettled in a new tissue, such as brain, lung or bone. This is metastatic cancer, and it’s the big killer—while precise numbers are scarce, anywhere from half to the large majority of cancer deaths have been attributed to metastasis. Offering people more options and hope will mean understanding how those cancers successfully migrate and recolonize.

The prevalence of metastasis belies the arduous journey that cancer cells must make to achieve it.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Failed Ideas That Drive Elon Musk

Jill Lepore in The New York Times:

Four years ago, I made a series for the BBC in which I located the origins of Mr. Musk’s strange sense of destiny in science fiction, some of it a century old. This year, revising the series, I was again struck by how little of what Mr. Musk proposes is new and by how many of his ideas about politics, governance and economics resemble those championed by his grandfather Joshua Haldeman, a cowboy, chiropractor, conspiracy theorist and amateur aviator known as the Flying Haldeman. Mr. Musk’s grandfather was also a flamboyant leader of the political movement known as technocracy.

Four years ago, I made a series for the BBC in which I located the origins of Mr. Musk’s strange sense of destiny in science fiction, some of it a century old. This year, revising the series, I was again struck by how little of what Mr. Musk proposes is new and by how many of his ideas about politics, governance and economics resemble those championed by his grandfather Joshua Haldeman, a cowboy, chiropractor, conspiracy theorist and amateur aviator known as the Flying Haldeman. Mr. Musk’s grandfather was also a flamboyant leader of the political movement known as technocracy.

Leading technocrats proposed replacing democratically elected officials and civil servants — indeed, all of government — with an army of scientists and engineers under what they called a technate. Some also wanted to annex Canada and Mexico. At technocracy’s height, one branch of the movement had more than a quarter of a million members. Under the technate, humans would no longer have names; they would have numbers. One technocrat went by 1x1809x56. (Mr. Musk has a son named X Æ A-12.) Mr. Haldeman, who had lost his Saskatchewan farm during the Depression, became the movement’s leader in Canada. He was technocrat No. 10450-1.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Val Kilmer (1959 – 2025) Actor

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

Why We Need Bodies

A song remains unheard unless it passes

through some body’s throat. This morning

I watched a wren nibble apart a beetle

and digest it into birdsong. Even air needs

loose-leafed trees to express its melancholy.

Everything invisible seeks a shape.

Remember how, in our dizzy younger years,

we tried to pour the abstraction of love

into the pink cup of each other’s mouth?

Now you kneel to tie my shoe (as you’ve done

daily since the stroke) and I telegraph my gratitude

by tapping the nipple mole cuddled in the small

of your back. Nights I slide my fingers

along the lines sloping down your cheek. I flatten

my hand on your chest to check for life

announcing its presence in your heartbeat steady

as a dog tail’s happy thump against the floor.

When I turn over you lightly clasp my left breast

which, for private reasons, you call Freckles.

by Judith Tate O’Brien

from Rattle Magazine #16, Winter 20011

|

—20

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, April 4, 2025

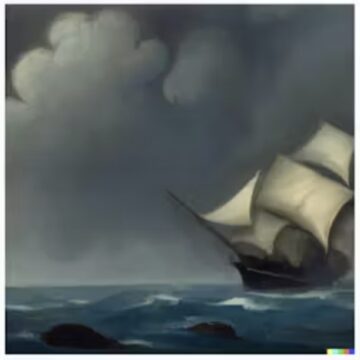

Chaos Bewitched: Moby-Dick and AI

Eigil zu Tage-Ravn in The Public Domain Review:

It is among the most memorable moments in American literature. At the start of Chapter Three of his masterwork, Moby-Dick (1851), Herman Melville has his protagonist, the existential castaway Ishmael, newly embarked on his fateful commitment to go a-whaling (is it a kind of suicide? a mere lark? both?), push open the door of a port-side rough-house for boozing mariners: the so-called “Spouter-Inn”. It is dark. It is dank. Savage weaponry from cannibal isles spikes the walls. And those who hunker at the bar are renegades and isolatoes, gruff men of the sea. In the half-light, Ishmael immediately discerns, in the entryway itself, like a warning over the threshold, “a very large oil-painting”.

It is among the most memorable moments in American literature. At the start of Chapter Three of his masterwork, Moby-Dick (1851), Herman Melville has his protagonist, the existential castaway Ishmael, newly embarked on his fateful commitment to go a-whaling (is it a kind of suicide? a mere lark? both?), push open the door of a port-side rough-house for boozing mariners: the so-called “Spouter-Inn”. It is dark. It is dank. Savage weaponry from cannibal isles spikes the walls. And those who hunker at the bar are renegades and isolatoes, gruff men of the sea. In the half-light, Ishmael immediately discerns, in the entryway itself, like a warning over the threshold, “a very large oil-painting”.

Ishmael pauses. He puzzles. He peers. He even goes so far as to pry open a little window in the vestibule, to shed some light on a most inscrutable, a most intractable, a most maddening canvas: “Such unaccountable masses of shades and shadows, that at first you almost thought some ambitious young artist, in the time of the New England hags, had endeavored to delineate chaos bewitched.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

First Therapy Chatbot Trial Yields Mental Health Benefits

Morgan Kelly at the website of Dartmouth:

Dartmouth researchers conducted the first-ever clinical trial of a generative AI-powered therapy chatbot and found that the software resulted in significant improvements in participants’ symptoms, according to results published March 27 in NEJM AI.

Dartmouth researchers conducted the first-ever clinical trial of a generative AI-powered therapy chatbot and found that the software resulted in significant improvements in participants’ symptoms, according to results published March 27 in NEJM AI.

People in the study also reported they could trust and communicate with the system, known as Therabot, to a degree that is comparable to working with a mental health professional.

The trial consisted of 106 people from across the United States diagnosed with major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or an eating disorder. Participants interacted with Therabot through a smartphone app by typing out responses to prompts about how they were feeling or initiating conversations when they needed to talk.

People diagnosed with depression experienced a 51% average reduction in symptoms, leading to clinically significant improvements in mood and overall well-being, the researchers report. Participants with generalized anxiety reported an average reduction in symptoms of 31%, with many shifting from moderate to mild anxiety, or from mild anxiety to below the clinical threshold for diagnosis.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Excerpt from Conan O’Brien’s Mark Twain Prize Acceptance Speech

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Are We Taking A.I. Seriously Enough?

Josh Rothman at The New Yorker:

Many people don’t know how seriously to take A.I. It can be hard to know, both because the technology is so new and because hype gets in the way. It’s wise to resist the sales pitch simply because the future is unpredictable. But anti-hype, which emerges as a kind of immune response to boosterism, doesn’t necessarily clarify matters. In 1879, the Times ran a multipart front-page story about the light bulb, under the headline “Edison’s Electric Light—Conflicting Statements as to Its Utility.” In a section offering “a scientific view,” the paper quoted an eminent engineer—the president of the Stevens Institute of Technology—who was “protesting against the trumpeting of the result of Edison’s experiments in electric lighting as ‘a wonderful success.’ ” He wasn’t being unreasonable: inventors had been failing to construct workable light bulbs for decades. In many other instances, his anti-hype would’ve been warranted.

Many people don’t know how seriously to take A.I. It can be hard to know, both because the technology is so new and because hype gets in the way. It’s wise to resist the sales pitch simply because the future is unpredictable. But anti-hype, which emerges as a kind of immune response to boosterism, doesn’t necessarily clarify matters. In 1879, the Times ran a multipart front-page story about the light bulb, under the headline “Edison’s Electric Light—Conflicting Statements as to Its Utility.” In a section offering “a scientific view,” the paper quoted an eminent engineer—the president of the Stevens Institute of Technology—who was “protesting against the trumpeting of the result of Edison’s experiments in electric lighting as ‘a wonderful success.’ ” He wasn’t being unreasonable: inventors had been failing to construct workable light bulbs for decades. In many other instances, his anti-hype would’ve been warranted.

A.I. hype has created two kinds of anti-hype. The first holds that the technology will soon plateau: maybe A.I. will continue struggling to plan ahead, or to think in an explicitly logical, rather than intuitive, way.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

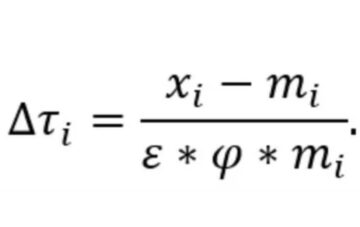

Why those tariff numbers?

Matt Lutz at Humean Being:

So Trump’s basic starting point is that he thinks trade deficits are bad. They’re not, but he thinks they are. He has this very dumb idea that a trade deficit is a deficit of trade, and the dollar amount of the trade deficit is the amount that other countries are cheating us out of through nefarious… I dunno, trading?

So Trump’s basic starting point is that he thinks trade deficits are bad. They’re not, but he thinks they are. He has this very dumb idea that a trade deficit is a deficit of trade, and the dollar amount of the trade deficit is the amount that other countries are cheating us out of through nefarious… I dunno, trading?

So his solution to this injustice is to try to inflict an equal and opposite amount of damage to the other country’s economy. If they’re taking X dollars from us in trade deficit, we’ll take X dollars from them in tariffs. And that’s precisely what the formula is supposed to do. The other country is stealing X dollars from us (per the trade deficit), so we’ll take X dollars right back (with a tariff).

So, a toy example: Suppose that there is another country that we import $100 of goods from and export $21 of goods to. That’s a trade deficit of $79.

More here. And more on this from Noah Smith here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

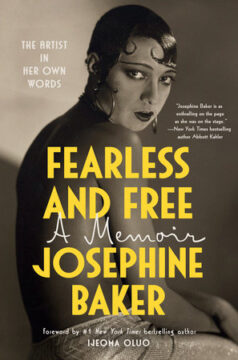

Josephine Baker

Lucy Moore at Literary Review:

Today we think of Josephine Baker as the personification of the Jazz Age – the skinny black kid from Missouri who took Paris by storm. In retrospect, her show-stopping Revue Nègre act can be read as a subversion of the prejudices of her age. At the time, however, it just looked like a heady cocktail of comedy, exoticism and sex. Scantily garlanded with feathers, dancing to ‘barbaric, syncopated music’, Baker was ‘black poetry’, according to Marcel Sauvage, who acted as her ghostwriter.

Today we think of Josephine Baker as the personification of the Jazz Age – the skinny black kid from Missouri who took Paris by storm. In retrospect, her show-stopping Revue Nègre act can be read as a subversion of the prejudices of her age. At the time, however, it just looked like a heady cocktail of comedy, exoticism and sex. Scantily garlanded with feathers, dancing to ‘barbaric, syncopated music’, Baker was ‘black poetry’, according to Marcel Sauvage, who acted as her ghostwriter.

The fact that she had got to Paris at all was testament to her resilience and spirit. Born into poverty in St Louis in 1906, Baker never knew who her real father was. By the age of eight she was working as a maid. At eleven, she witnessed the devastating racist violence of the East St Louis massacre. Two years later, having dropped out of school, she was scraping together a living dancing on street corners. She was married – the first time at only thirteen – and divorced twice before she was twenty.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Scott Alexander & Daniel Kokotajlo: 2027 Intelligence Explosion

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Travelers to Unimaginable Lands: Stories of Dementia, the Caregiver, and the Human Brain

Norman Doidge in Tablet:

Travelers to Unimaginable Lands is that rarity: true biblio-therapy. Lucid, mature, wise, with hardly a wasted word, it not only deepens our understanding of what transpires as we care for a loved one with Alzheimer’s, it also has the potential to be powerfully therapeutic, offering the kind of support and reorientation so essential to the millions of people struggling with the long, often agonizing leave-taking of loved ones stricken with the dreaded disease. The book is based on a profound insight: the concept of “dementia blindness,” which identifies a singular problem of caring for people with dementia disorders—one that has generally escaped notice but, once understood, may make a significant difference for many caregivers.

Travelers to Unimaginable Lands is that rarity: true biblio-therapy. Lucid, mature, wise, with hardly a wasted word, it not only deepens our understanding of what transpires as we care for a loved one with Alzheimer’s, it also has the potential to be powerfully therapeutic, offering the kind of support and reorientation so essential to the millions of people struggling with the long, often agonizing leave-taking of loved ones stricken with the dreaded disease. The book is based on a profound insight: the concept of “dementia blindness,” which identifies a singular problem of caring for people with dementia disorders—one that has generally escaped notice but, once understood, may make a significant difference for many caregivers.

Elegantly written and accessible, Travelers is full of frank, lively, and illuminating conversations between the author, Dasha Kiper, and caregivers, which explore the ways caregivers get stuck in patterns hard to escape.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Is Lifetime Cancer Risk Determined Before Birth?

Hannah Thomasy in The Scientist:

In 2015, scientists made a surprising discovery about physiologically normal human skin: More than 25 percent of cells carried genetic mutations known to cause cancer and the average number of mutations per cell was similar to the burden observed in many tumors.1 This research demonstrated that while genetic mutations are critical drivers of cancer development, other factors also play key roles. Indeed, scientists are increasingly finding that epigenetic factors, which do not change the genetic code but can drastically alter gene expression, are important for cancer risk and resilience as well.

In 2015, scientists made a surprising discovery about physiologically normal human skin: More than 25 percent of cells carried genetic mutations known to cause cancer and the average number of mutations per cell was similar to the burden observed in many tumors.1 This research demonstrated that while genetic mutations are critical drivers of cancer development, other factors also play key roles. Indeed, scientists are increasingly finding that epigenetic factors, which do not change the genetic code but can drastically alter gene expression, are important for cancer risk and resilience as well.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

Metropolis with Ghazal

scream, prosper. Tonight, dream up this druglicked city.

by Siddharth Dasgupta

from Rattle Magazine

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, April 3, 2025

The Colors Of Her Coat

Scott Alexander at Astral Codex Ten:

In Ballad of the White Horse, G.K. Chesterton describes the Virgin Mary:

Her face was like an open word

When brave men speak and choose,

The very colours of her coat

Were better than good news.

Why the colors of her coat?

The medievals took their dyes very seriously. This was before modern chemistry, so you had to try hard if you wanted good colors. Try hard they did; they famously used literal gold, hammered into ultrathin sheets, to make golden highlights.

Blue was another tough one. You could do mediocre, half-faded blues with azurite. But if you wanted perfect blue, the color of the heavens on a clear evening, you needed ultramarine.

Here is the process for getting ultramarine. First, go to Afghanistan. Keep in mind, you start in England or France or wherever. Afghanistan is four thousand miles away. Your path takes you through tall mountains, burning deserts, and several dozen Muslim countries that are still pissed about the whole Crusades thing. Still alive? Climb 7,000 feet through the mountains of Kuran Wa Munjan…

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Dazzling Complexity of the Frozen World

Jaime Herndon at Undark:

It’s an iconic image: A polar bear perched on a lone ice cap, drifting at sea. Is that the fate climate change has in store for this powerful Arctic inhabitant? In 2004, the discovery of a fossil polar bear jaw on Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago, suggested another possibility. The fossil came from a bear that had lived between 110,000 and 130,000 years ago, an era that was warm — even warmer than today.

It’s an iconic image: A polar bear perched on a lone ice cap, drifting at sea. Is that the fate climate change has in store for this powerful Arctic inhabitant? In 2004, the discovery of a fossil polar bear jaw on Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago, suggested another possibility. The fossil came from a bear that had lived between 110,000 and 130,000 years ago, an era that was warm — even warmer than today.

But studies of the genome extracted from the fossil showed the ancient bear had much greater genetic diversity than modern polar bears. Scientists hypothesized that when ice diminished in previous millennia, polar bears moved to land and interbred with brown bears, whose genes could have helped them adapt to the warmer weather. With possibly fewer genetic resources, today’s polar bears may not fare as well.

That’s one of the many unexpected discoveries covered in “Ends of the Earth: Journeys to the Polar Regions in Search of Life, the Cosmos, and Our Future,” the latest book by paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin. And the tenuous fate of the polar bear hints at the question at the heart of his narrative: What is it about the polar regions that seems so important to our understanding of the environment — and ourselves?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.