Rebecca Ruth Gould at JSTOR Daily:

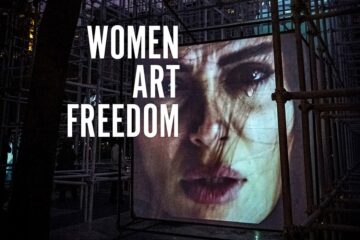

“What if we view street activities not as organic, evolving phenomena but as calculated efforts to challenge and subvert the state rules governing street dynamics?” Pamela Karimi asks in Women, Art, Freedom: Artists and Street Politics in Iran, her study of work that has emerged from the protest movement of the same name that began in 2022. This question guides Karimi as she endeavors to understand artistic production in an age of political repression and upheaval across the region and world. An architect and associate professor of art and architectural history at Cornell University, Karimi brings her considerable expertise to bear on the contemporary struggle for women’s freedom in Iran and its formidable creative legacies, introducing along the way the pioneering artists who are responding to the recent uprising in the country.

“What if we view street activities not as organic, evolving phenomena but as calculated efforts to challenge and subvert the state rules governing street dynamics?” Pamela Karimi asks in Women, Art, Freedom: Artists and Street Politics in Iran, her study of work that has emerged from the protest movement of the same name that began in 2022. This question guides Karimi as she endeavors to understand artistic production in an age of political repression and upheaval across the region and world. An architect and associate professor of art and architectural history at Cornell University, Karimi brings her considerable expertise to bear on the contemporary struggle for women’s freedom in Iran and its formidable creative legacies, introducing along the way the pioneering artists who are responding to the recent uprising in the country.

Using imagery, interviews, avant-garde magazines, and feminist manifestos to situate Iranian artistic production both within Iran and in the diaspora, Karimi concentrates on work that engages with the “politics of the street” in the broadest sense.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

O

O A

A On March 19, 2024, we emailed the psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, inviting him to appear on our podcast, “Lives Well Lived,” and suggesting a date in May. He replied promptly, saying that he would not be available then because he was on his way to Switzerland, where, despite being relatively healthy at 90, he planned to die by assisted suicide on March 27.

On March 19, 2024, we emailed the psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, inviting him to appear on our podcast, “Lives Well Lived,” and suggesting a date in May. He replied promptly, saying that he would not be available then because he was on his way to Switzerland, where, despite being relatively healthy at 90, he planned to die by assisted suicide on March 27. Today’s AI technologies are based on deep learning, yet “AI” is commonly equated with large language models, and the fundamental nature of deep learning and LLMs is obscured by talk of using “statistical patterns” to “predict tokens”. This token-focused framing has been a remarkably effective way to misunderstand AI.

Today’s AI technologies are based on deep learning, yet “AI” is commonly equated with large language models, and the fundamental nature of deep learning and LLMs is obscured by talk of using “statistical patterns” to “predict tokens”. This token-focused framing has been a remarkably effective way to misunderstand AI. In recent decades, a paradox has haunted American political life. Given that political progressives wielded considerable political, economic, and cultural influence, how is it possible that our actual social order was so resistant to real change? Why did the black-white wealth gap remain unchanged, and why did economic inequality steadily increase? Why did basic access to affordable housing plummet? And why has higher education become a nightmarish debt sentence for poor and underprivileged people seeking a better life?

In recent decades, a paradox has haunted American political life. Given that political progressives wielded considerable political, economic, and cultural influence, how is it possible that our actual social order was so resistant to real change? Why did the black-white wealth gap remain unchanged, and why did economic inequality steadily increase? Why did basic access to affordable housing plummet? And why has higher education become a nightmarish debt sentence for poor and underprivileged people seeking a better life? Mishra is a relative latecomer to the Palestinian cause. It was Israeli heroes, not Arabs, with whom he was infatuated as a boy growing up in India: he even had a picture on his wall of Moshe Dayan, Israel’s defence minister during the Six Day War. Conversion came during a 2008 visit to Israel-Palestine, where Mishra was shocked to witness the humiliations heaped on the inhabitants of the West Bank. “Nothing prepared me for the brutality and squalor of Israel’s occupation,” he writes, “the snaking wall and numerous roadblocks … meant to torment Palestinians in their own land … the racially exclusive network of shiny asphalt roads, electricity grids and water systems linking the illegal Jewish settlements to Israel.”

Mishra is a relative latecomer to the Palestinian cause. It was Israeli heroes, not Arabs, with whom he was infatuated as a boy growing up in India: he even had a picture on his wall of Moshe Dayan, Israel’s defence minister during the Six Day War. Conversion came during a 2008 visit to Israel-Palestine, where Mishra was shocked to witness the humiliations heaped on the inhabitants of the West Bank. “Nothing prepared me for the brutality and squalor of Israel’s occupation,” he writes, “the snaking wall and numerous roadblocks … meant to torment Palestinians in their own land … the racially exclusive network of shiny asphalt roads, electricity grids and water systems linking the illegal Jewish settlements to Israel.”

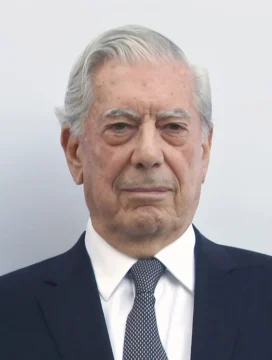

Once upon a time, during the last quarter of the 20th century, it was possible to argue that one person was America’s best novelist and best literary critic. I am talking about John Updike, whose long and elegant reviews in The New Yorker set reading agendas. Such was Updike’s influence that readers paid heed when, in the mid-1980s, he developed a sustained literary man-crush on the Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa, who died on Sunday at 89.

Once upon a time, during the last quarter of the 20th century, it was possible to argue that one person was America’s best novelist and best literary critic. I am talking about John Updike, whose long and elegant reviews in The New Yorker set reading agendas. Such was Updike’s influence that readers paid heed when, in the mid-1980s, he developed a sustained literary man-crush on the Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa, who died on Sunday at 89. T

T THE world is angry — and in most places, women bear the brunt of this anger. This International Women’s Day, the

THE world is angry — and in most places, women bear the brunt of this anger. This International Women’s Day, the