Ingrid Wickelgren in Quanta:

DNA is often compared to a written language. The metaphor leaps out: Like letters of the alphabet, molecules (the nucleotide bases A, T, C and G, for adenine, thymine, cytosine and guanine) are arranged into sequences — words, paragraphs, chapters, perhaps — in every organism, from bacteria to humans. Like a language, they encode information. But humans can’t easily read or interpret these instructions for life. We cannot, at a glance, tell the difference between a DNA sequence that functions in an organism and a random string of A’s, T’s, C’s and G’s.

DNA is often compared to a written language. The metaphor leaps out: Like letters of the alphabet, molecules (the nucleotide bases A, T, C and G, for adenine, thymine, cytosine and guanine) are arranged into sequences — words, paragraphs, chapters, perhaps — in every organism, from bacteria to humans. Like a language, they encode information. But humans can’t easily read or interpret these instructions for life. We cannot, at a glance, tell the difference between a DNA sequence that functions in an organism and a random string of A’s, T’s, C’s and G’s.

“It’s really hard for humans to understand biological sequence,” said the computer scientist Brian Hie(opens a new tab), who heads the Laboratory of Evolutionary Design at Stanford University, based at the nonprofit Arc Institute(opens a new tab). This was the impetus behind his new invention, named Evo: a genomic large language model (LLM), which he describes as ChatGPT for DNA.

ChatGPT was trained on large volumes of written English text, from which the algorithm learned patterns that let it read and write original sentences. Similarly, Evo was trained(opens a new tab) on large volumes of DNA — 300 billion base pairs from 2.7 million bacterial, archaeal and viral genomes — to glean functional information from stretches of DNA that a user inputs as prompts.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Political outcomes would be relatively simple to predict and understand if only people were well-informed, entirely rational, and perfectly self-interested. Alas, real human beings are messy, emotional, imperfect creatures, so a successful theory of politics has to account for these features. One phenomenon that has grown in recent years is an alignment of cultural differences with political ones, so that polarization becomes more entrenched and even violent. I talk with political scientist Lilliana Mason about how this has come to pass, and how democracy can deal with it.

Political outcomes would be relatively simple to predict and understand if only people were well-informed, entirely rational, and perfectly self-interested. Alas, real human beings are messy, emotional, imperfect creatures, so a successful theory of politics has to account for these features. One phenomenon that has grown in recent years is an alignment of cultural differences with political ones, so that polarization becomes more entrenched and even violent. I talk with political scientist Lilliana Mason about how this has come to pass, and how democracy can deal with it.

Monterroso has often been compared to Borges, and the comparisons are generally pretty apt. Both writers preoccupied themselves, formally, with short stories and essays that seem to merge into one another; both had a playful interest in scholarly arcana; both were obsessed with the question of style; and both were fascinated by parables and fables. But compared with the ironclad intertextuality of a writer like Borges, Monterroso’s own brand of self-referentiality isn’t exactly philosophically sound—a result, probably, of his antic disposition. It doesn’t approach, or even attempt to approach, the ideal of a closed system. Read a Borges story, and you often get a sense of the author going solemnly about his work like a monk. In a Monterroso story, the image called to mind is rather that of a clerk—one who is lazy, or bad at his job, or poorly trained, or some combination of the three. Things seem simply to have been misfiled.

Monterroso has often been compared to Borges, and the comparisons are generally pretty apt. Both writers preoccupied themselves, formally, with short stories and essays that seem to merge into one another; both had a playful interest in scholarly arcana; both were obsessed with the question of style; and both were fascinated by parables and fables. But compared with the ironclad intertextuality of a writer like Borges, Monterroso’s own brand of self-referentiality isn’t exactly philosophically sound—a result, probably, of his antic disposition. It doesn’t approach, or even attempt to approach, the ideal of a closed system. Read a Borges story, and you often get a sense of the author going solemnly about his work like a monk. In a Monterroso story, the image called to mind is rather that of a clerk—one who is lazy, or bad at his job, or poorly trained, or some combination of the three. Things seem simply to have been misfiled. Christopher Nolan’s film The Prestige presents a three-act structure said to apply to all great magic tricks. First is the pledge: the magician presents something ordinary, though the audience suspects that it isn’t. Next is the turn: the magician makes this ordinary object do something extraordinary, like disappear. Finally, there’s the prestige: the truly astounding moment, as when the object reappears in an unexpected way.

Christopher Nolan’s film The Prestige presents a three-act structure said to apply to all great magic tricks. First is the pledge: the magician presents something ordinary, though the audience suspects that it isn’t. Next is the turn: the magician makes this ordinary object do something extraordinary, like disappear. Finally, there’s the prestige: the truly astounding moment, as when the object reappears in an unexpected way. In Washington, DC, the city currently home to America’s least popular president ever, the mainstream media “broke” the story that a rash of black girls had gone missing. Social networking platforms circulated hashtags and headlines speculating the girls had been abducted and forced into sex work. Others worried the girls were dead. The police countered all theories by assuring local and national worriers that these missing black girls were merely runaways.

In Washington, DC, the city currently home to America’s least popular president ever, the mainstream media “broke” the story that a rash of black girls had gone missing. Social networking platforms circulated hashtags and headlines speculating the girls had been abducted and forced into sex work. Others worried the girls were dead. The police countered all theories by assuring local and national worriers that these missing black girls were merely runaways.

It is reasonable to assume that more than 15 months of pulverizing conflict have changed the perceptions of ordinary civilians in the territory about what they want for their future, how they see their land, who they think should be their rulers, and what they consider to be the most plausible pathways to peace. Given the extraordinary price they have paid for Hamas’s actions on October 7, 2023, Gazans might be expected to reject the group and favor a different leadership. Similarly, outside observers might anticipate that after so much hardship, Gazans would be more prepared to compromise on larger political aspirations in favor of more urgent human needs.

It is reasonable to assume that more than 15 months of pulverizing conflict have changed the perceptions of ordinary civilians in the territory about what they want for their future, how they see their land, who they think should be their rulers, and what they consider to be the most plausible pathways to peace. Given the extraordinary price they have paid for Hamas’s actions on October 7, 2023, Gazans might be expected to reject the group and favor a different leadership. Similarly, outside observers might anticipate that after so much hardship, Gazans would be more prepared to compromise on larger political aspirations in favor of more urgent human needs. “If we want to create a super-intelligent AI,” a friend said to me, “all we need to do is digitize the brain of Terry Tao.” A Fields Medal–winning mathematician, Tao is both prodigious (he was the youngest ever winner of the International Mathematical Olympiad) and prolific (his 300+ papers span vast areas of pure and applied math). Uploading Tao to the cloud remains a ways off, but it turns out that Terry himself has recently become interested in a related problem — how to digitize the process of mathematical research.

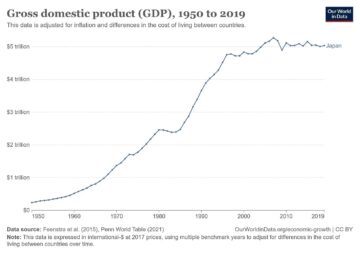

“If we want to create a super-intelligent AI,” a friend said to me, “all we need to do is digitize the brain of Terry Tao.” A Fields Medal–winning mathematician, Tao is both prodigious (he was the youngest ever winner of the International Mathematical Olympiad) and prolific (his 300+ papers span vast areas of pure and applied math). Uploading Tao to the cloud remains a ways off, but it turns out that Terry himself has recently become interested in a related problem — how to digitize the process of mathematical research. For more than three decades, Japan has endured near complete economic stagnation. Since 2000, Japan’s total output has grown by only

For more than three decades, Japan has endured near complete economic stagnation. Since 2000, Japan’s total output has grown by only Andrea West remembers the first time she heard about a new class of migraine medication that could end her decades of pain. It was 2021 and she heard a scientist on the radio discussing the

Andrea West remembers the first time she heard about a new class of migraine medication that could end her decades of pain. It was 2021 and she heard a scientist on the radio discussing the  Black Women Are The Mules Of The Earth is a quote from Zora Neale Hurston who spoke through the heroine Janie Crawford in her 1937 book, ‘Their Eyes Were Watching God’. I began to grapple with the imagery that statement elicited, whether I should interpret it as praise for our strength or a derogating description that is symbolic of victimization and bondage. African Americans are faced with the psychological challenge of reconciling with an African Heritage and an European upbringing and education, thus bringing about a multi-facetted conception of self. W.E.B DuBois called this double consciousness, which is a sense of always looking at oneself through the eyes of another. Based in popular culture, the black female iconography has been the saviors, cooks, cleaners, caretakers of their children and other people’s children, the ones responsible for making things better that we didn’t mess up in the first place, the sex objects, superheroes, the magical negro, the ones that are everything to everyone while operating under a public gaze that has constructed this superhuman stereotype. Without being conscious of it, our culture’s imagination is eager to distort black women and dehumanize us.

Black Women Are The Mules Of The Earth is a quote from Zora Neale Hurston who spoke through the heroine Janie Crawford in her 1937 book, ‘Their Eyes Were Watching God’. I began to grapple with the imagery that statement elicited, whether I should interpret it as praise for our strength or a derogating description that is symbolic of victimization and bondage. African Americans are faced with the psychological challenge of reconciling with an African Heritage and an European upbringing and education, thus bringing about a multi-facetted conception of self. W.E.B DuBois called this double consciousness, which is a sense of always looking at oneself through the eyes of another. Based in popular culture, the black female iconography has been the saviors, cooks, cleaners, caretakers of their children and other people’s children, the ones responsible for making things better that we didn’t mess up in the first place, the sex objects, superheroes, the magical negro, the ones that are everything to everyone while operating under a public gaze that has constructed this superhuman stereotype. Without being conscious of it, our culture’s imagination is eager to distort black women and dehumanize us. RD said:

RD said: DNA is often compared to a written language. The metaphor leaps out: Like letters of the alphabet, molecules (the nucleotide bases A, T, C and G, for adenine, thymine, cytosine and guanine) are arranged into sequences — words, paragraphs, chapters, perhaps — in every organism, from bacteria to humans. Like a language, they encode information. But humans can’t easily read or interpret these instructions for life. We cannot, at a glance, tell the difference between a DNA sequence that functions in an organism and a random string of A’s, T’s, C’s and G’s.

DNA is often compared to a written language. The metaphor leaps out: Like letters of the alphabet, molecules (the nucleotide bases A, T, C and G, for adenine, thymine, cytosine and guanine) are arranged into sequences — words, paragraphs, chapters, perhaps — in every organism, from bacteria to humans. Like a language, they encode information. But humans can’t easily read or interpret these instructions for life. We cannot, at a glance, tell the difference between a DNA sequence that functions in an organism and a random string of A’s, T’s, C’s and G’s.