Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Sunday Poem

By the Sea

I.

To watch a seagull fly overhead,

a girl child on the beach in red pajamas

tilts her head back and back,

impossibly back to anyone a second older.

Now she digs a hole

tossing the sand back between her legs

as if her hands were forepaws.

Now she sits on her haunches

in the hole and draws a circle

all about herself.

Now she is safe from everything.

//////II.

//////a seagull settles

………. on a translucent

………. restaurant umbrella

………. a little girl begins

………. to twirl it

………. the seagull spins

………. around three times

………. as if riding

………. a merry-go-round,

………. then flies away

III.

Low winter sun

………. on a black tarnish of sea

a crooked line of pelicans

………. serene and slow

riding the low air

………. above the breaking water

………. IV.

………. light shining on the sea’s

………. not interested in what’s beneath

………. it plays on the surface

………. rolls under a wave but out

………. before it breaks

………. it rides over the white foam

………. where the water caught

………. between the going out

………. and coming back is

………. almost still

by Nils Peterson

from All the Marvelous Stuff

Caesura Editions 2019

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, March 28, 2025

The Biggest Loser

Luke Winkie in Slate:

“People give estimates of what they think we’re making, and it’s always way low,” he told me from the plush interior of his Rolls-Royce, which was still scented with a synthetic new-purchase aroma. “Our watch hours on YouTube [in December] were, like, 5.7 million hours. And there’s a commercial every 10 minutes.”

“People give estimates of what they think we’re making, and it’s always way low,” he told me from the plush interior of his Rolls-Royce, which was still scented with a synthetic new-purchase aroma. “Our watch hours on YouTube [in December] were, like, 5.7 million hours. And there’s a commercial every 10 minutes.”

Vegas Matt was on the cusp of a remarkable achievement. In a matter of weeks, his YouTube channel would cross the million-subscriber mark—a metric that pairs nicely with the million or so people who follow his Instagram account, and the 685,000 on his TikTok. New videos appear daily, and they all follow the same format: First, Vegas Matt counts out a hefty wager in front of a blackjack table or a slot machine. Then, like so many gamblers, he simply tries his luck. The camera is framed to provide the illusion that the viewer is in the captain’s chair, preparing to immolate $3,000 on the altar of chance. Throughout all this, Vegas Matt displays no elite strategy, acumen, or gamesmanship. He does not claim to have an insider’s edge or an esoteric jackpot-juicing technique. No one watching his videos is going to pick up tips to improve their approach. But that’s the magic: He’s utterly relatable.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

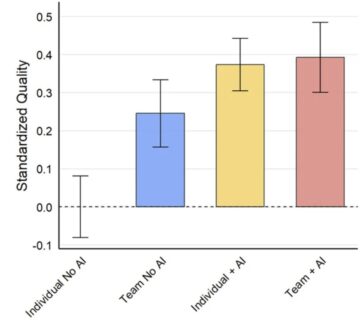

Having an AI on your team can increase performance

Ethan Mollick at One Useful Thing:

Over the past couple years, we have learned that AI can boost the productivity of individual knowledge workers ranging from consultants to lawyers to coders. But most knowledge work isn’t purely an individual activity; it happens in groups and teams. And teams aren’t just collections of individuals – they provide critical benefits that individuals alone typically can’t, including better performance, sharing of expertise, and social connections.

Over the past couple years, we have learned that AI can boost the productivity of individual knowledge workers ranging from consultants to lawyers to coders. But most knowledge work isn’t purely an individual activity; it happens in groups and teams. And teams aren’t just collections of individuals – they provide critical benefits that individuals alone typically can’t, including better performance, sharing of expertise, and social connections.

So, what happens when AI acts as a teammate? This past summer we conducted a pre-registered, randomized controlled trial of 776 professionals at Procter and Gamble, the consumer goods giant, to find out.

We are ready to share the results in a new working paper: The Cybernetic Teammate: A Field Experiment on Generative AI Reshaping Teamwork and Expertise.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Geoffrey Hinton, Official Nobel Prize interview

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Avoiding your neighbor because of how they voted? Democracy needs you to talk to them instead

Betsy Sinclair at The Conversation:

Political scientists Steven Webster, Elizabeth Connors and I have investigated what happens to people’s social networks – their friends, family and neighbors – when partisan anger takes over. For example, suppose your neighbor is a member of the opposite political party. You’ve always watered their plants when they go on vacation. Given the news these days and how angry you’re feeling, what will you say when they ask for help during their next trip?

Political scientists Steven Webster, Elizabeth Connors and I have investigated what happens to people’s social networks – their friends, family and neighbors – when partisan anger takes over. For example, suppose your neighbor is a member of the opposite political party. You’ve always watered their plants when they go on vacation. Given the news these days and how angry you’re feeling, what will you say when they ask for help during their next trip?

We found that when someone is angry with the opposite party, they avoid people with those views. That can include not assisting neighbors with various tasks, avoiding social gatherings attended by people from the other side, and refusing to date people who vote differently. It means being disappointed if your son or daughter marries a supporter of the opposing party, and even severing close friendships or distancing yourself from close relatives.

We see that political anger disrupts ordinary life – coffee with a friend – as well as more major life decisions. Political anger breaks our social networks.

People rely on their relationships to understand our world – and to vote. The more we isolate ourselves from people who see things differently, the easier it is to misunderstand them, pushing us to separate even more.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Romanticism, Politics, & Ethics – Isaiah Berlin (1963)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Soft Skills

Lily Scherlis at Harper’s Magazine:

Soft-skills researchers have themselves been mired in their own long crisis. None of them have convincingly determined what a “soft skill” even is, despite decades of research. “There is still lack of consensus regarding the definitions,” a team of management scientists wrote in a 2022 article entitled “Soft Skills, Do We Know What We Are Talking About?” Social scientists patch together definitions from an inconsistent taxonomy of subskills: communication skills, interpersonal skills, empathy, emotional intelligence, problem-solving skills, teamwork and collaboration, critical thinking, flexibility, creativity, leadership and social influence, resilience, adaptability. One group of management researchers attempted to connect the dots in 2023, writing that these skills are “non-technical and non-reliant on abstract reasoning involving interpersonal and intrapersonal abilities to facilitate mastered performance in particular social contexts.” USAID researchers once inventoried a whopping seventy-four different metrics for measuring soft skills; they found that the most common parameter was “self-control.”

Soft-skills researchers have themselves been mired in their own long crisis. None of them have convincingly determined what a “soft skill” even is, despite decades of research. “There is still lack of consensus regarding the definitions,” a team of management scientists wrote in a 2022 article entitled “Soft Skills, Do We Know What We Are Talking About?” Social scientists patch together definitions from an inconsistent taxonomy of subskills: communication skills, interpersonal skills, empathy, emotional intelligence, problem-solving skills, teamwork and collaboration, critical thinking, flexibility, creativity, leadership and social influence, resilience, adaptability. One group of management researchers attempted to connect the dots in 2023, writing that these skills are “non-technical and non-reliant on abstract reasoning involving interpersonal and intrapersonal abilities to facilitate mastered performance in particular social contexts.” USAID researchers once inventoried a whopping seventy-four different metrics for measuring soft skills; they found that the most common parameter was “self-control.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Happy Hundredth Birthday, Flannery O’Connor!

Jamie Quatro at The Paris Review:

Mary Flannery was born on the Feast of the Annunciation, the day marking the angel Gabriel’s announcement that Mary would bear the Christ child. O’Connor’s Irish Catholic parents, Edward and Regina, bracketed this festal birth by having her baptized on Easter Sunday, three weeks later. Each time I’ve visited O’Connor’s childhood home in Savannah, I’ve been moved by the Kiddie-Koop crib beneath the window in Regina’s bedroom, facing the twin green spires of Saint John the Baptist, the O’Connors’ church. The “crib” is a rectangular box with screens enclosing the four sides and the top. The cagelike design—a chicken coop for babies, really—was meant to allow mothers to leave children unattended. “Danger or Safety—Which?” one Kiddie-Koop advertisement read.

Mary Flannery was born on the Feast of the Annunciation, the day marking the angel Gabriel’s announcement that Mary would bear the Christ child. O’Connor’s Irish Catholic parents, Edward and Regina, bracketed this festal birth by having her baptized on Easter Sunday, three weeks later. Each time I’ve visited O’Connor’s childhood home in Savannah, I’ve been moved by the Kiddie-Koop crib beneath the window in Regina’s bedroom, facing the twin green spires of Saint John the Baptist, the O’Connors’ church. The “crib” is a rectangular box with screens enclosing the four sides and the top. The cagelike design—a chicken coop for babies, really—was meant to allow mothers to leave children unattended. “Danger or Safety—Which?” one Kiddie-Koop advertisement read.

I can’t help picturing O’Connor as a toddler growing up “in the shadow of the church,” literally and figuratively, standing in the Koop and peering through a double scrim of screen and windowpanes. When her eyesight failed, she began wearing thick corrective lenses—another layer of remove. And when she contracted the lupus that killed her father, her body itself became a kind of cage. “The wolf, I’m afraid, is inside tearing up the place,” she wrote to her friend Sister Mariella Gable one month before her passing at the age of thirty-nine.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Outwitting History: The Brutalist’s shallow sense of the past

Arielle Isack in The Point:

Adrien Brody is the most beautiful man in Hollywood, and maybe on the planet. This has to do with the unlikely features of his face: it is profoundly narrow, with a pair of high brows sloping gently away from one another and a resolutely expressive pair of very thin lips, both ideally situated in orbit of a truly promontory, ponderous nose. He is tall and very thin, like Timothée Chalamet under a rolling pin, and has great hair too; his thick brunette waves lend him a perma-rakishness that stays intact throughout the horrors of World War II that his characters tend to have to endure. Brody is best known for portraying attractive, talented Holocaust survivors: Before The Brutalist, his best-known role was in Roman Polanski’s 2002 film The Pianist, in which he plays a Polish virtuoso pianist who narrowly escapes getting sent to Treblinka. In his latest, directed by Brady Corbet, he is László Tóth, an accomplished Hungarian architect who survives Buchenwald and emigrates to Pennsylvania.

Adrien Brody is the most beautiful man in Hollywood, and maybe on the planet. This has to do with the unlikely features of his face: it is profoundly narrow, with a pair of high brows sloping gently away from one another and a resolutely expressive pair of very thin lips, both ideally situated in orbit of a truly promontory, ponderous nose. He is tall and very thin, like Timothée Chalamet under a rolling pin, and has great hair too; his thick brunette waves lend him a perma-rakishness that stays intact throughout the horrors of World War II that his characters tend to have to endure. Brody is best known for portraying attractive, talented Holocaust survivors: Before The Brutalist, his best-known role was in Roman Polanski’s 2002 film The Pianist, in which he plays a Polish virtuoso pianist who narrowly escapes getting sent to Treblinka. In his latest, directed by Brady Corbet, he is László Tóth, an accomplished Hungarian architect who survives Buchenwald and emigrates to Pennsylvania.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Why ‘Adolescence’ is inescapable right now

Anne Banigin in The Washington Post:

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

Romanticism 101

Then I realized I hadn’t secured the boat.

Then I realized my friend had lied to me.

Then I realized my dog was gone

no matter how much I called in the rain.

All was change.

Then I realized I was surrounded by aliens

disguised as orthodontists having a convention

at the hotel breakfast bar.

Then I could see into the life of things,

that systems seek only to reproduce

the conditions of their own reproduction.

If I had to pick between shadows

and essences, I’d pick shadows.

They’re better dancers.

They always sing their telegrams.

Their old gods do not die.

Then I realized the very futility was salvation

in this greeny entanglement of breaths.

Yeah, as if.

The I realized even when you catch the mechanism,

the trick still works.

Then I came to Texas

and realized rockabilly would never go away.

Then I realized I’d been drugged.

We were all chasing nothing

which left no choice but to intensify the chase.

I came to handcuffed and gagged.

I came to intubated and packed in some kind of foam.

This to is how ash moves through water.

And all this time the side doors unlocked.

The I realized repetition could be an ending.

The I realized repetition could be an ending.

by Dean Young

from Poetry Magazine, July/August 2014.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, March 27, 2025

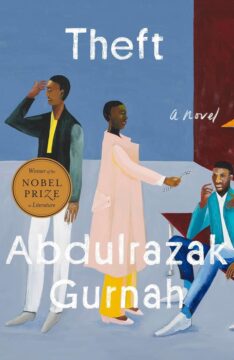

Nobel laureate Abdulrazak Gurnah’s new novel “Theft”

Max Callimanopulos in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

“Leaving. I’ve had years to think about that, leaving and arriving,” Latif, a Zanzibari emigre, tells us in Abdulrazak Gurnah’s 2001 novel By the Sea. The book describes the complicated friendship between two Zanzibari men living in the United Kingdom, but in these lines, Gurnah might as well be writing about himself. In 1968, Gurnah left his home—the small tropical island of Zanzibar, 20-odd miles off the coast of Tanzania—for Britain. He was seeking asylum: four years earlier, insurrectionists led by a Ugandan bricklayer named John Okello had risen up against the island’s landholding Arab minority in what would probably be called a genocide if it happened today. Okello himself boasted that some 12,000 Arabs were killed. Gurnah, whose people came from Yemen, was forced to flee Zanzibar. He was 18 years old when he arrived in England.

“Leaving. I’ve had years to think about that, leaving and arriving,” Latif, a Zanzibari emigre, tells us in Abdulrazak Gurnah’s 2001 novel By the Sea. The book describes the complicated friendship between two Zanzibari men living in the United Kingdom, but in these lines, Gurnah might as well be writing about himself. In 1968, Gurnah left his home—the small tropical island of Zanzibar, 20-odd miles off the coast of Tanzania—for Britain. He was seeking asylum: four years earlier, insurrectionists led by a Ugandan bricklayer named John Okello had risen up against the island’s landholding Arab minority in what would probably be called a genocide if it happened today. Okello himself boasted that some 12,000 Arabs were killed. Gurnah, whose people came from Yemen, was forced to flee Zanzibar. He was 18 years old when he arrived in England.

Gurnah has lived in the UK ever since. By all appearances, he gets on quite well there. He earned his doctorate at the University of Kent and has taught English and postcolonial literature there since the early 1980s. In 1987, he published his debut novel, Memory of Departure, and since then has pushed out a book every few years, to modest sales and good reviews. In 2021, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. “I thought it was a prank,” he told The Guardian, reacting to his win. In the speeches and interviews he gives, Gurnah comes across as a thoughtful, well-spoken, sensible man.

But to read four or five of his novels in succession is to realize that this is a writer still wracked by his decision, made 57 years ago, to leave Zanzibar.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Faust (1926) Murnau’s Masterpiece

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Abel Prize Awarded to Japanese Mathematician, Masaki Kashiwara, Who Abstracted Abstractions

Kenneth Chang in the New York Times:

Masaki Kashiwara, a Japanese mathematician, received this year’s Abel Prize, which aspires to be the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in math. Dr. Kashiwara’s highly abstract work combined algebra, geometry and differential equations in surprising ways.

Masaki Kashiwara, a Japanese mathematician, received this year’s Abel Prize, which aspires to be the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in math. Dr. Kashiwara’s highly abstract work combined algebra, geometry and differential equations in surprising ways.

The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, which manages the Abel Prize, announced the honor on Wednesday morning.

“First of all, he has solved some open conjectures — hard problems that have been around,” said Helge Holden, chairman of the prize committee. “And second, he has opened new avenues, connecting areas that were not known to be connected before. This is something that always surprises mathematicians.”

Mathematicians use connections between different areas of math to tackle recalcitrant problems, allowing them to recast those problems into concepts they better understand.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

‘Vietdamned’ by Clive Webb

Yuan Yi Zhu at History Today:

In 1966 and 1967 a group of left-wing intellectuals and radical activists, recruited by the nonagenarian philosopher Bertrand Russell, constituted themselves into a self-proclaimed ‘tribunal’ to try the United States of America for its conduct in Vietnam. After holding hearings in Sweden and in Denmark, they convicted the US of waging an illegal war of aggression against Vietnam, of war crimes and, most sensationally, of ‘genocide against the people of Vietnam’.

In 1966 and 1967 a group of left-wing intellectuals and radical activists, recruited by the nonagenarian philosopher Bertrand Russell, constituted themselves into a self-proclaimed ‘tribunal’ to try the United States of America for its conduct in Vietnam. After holding hearings in Sweden and in Denmark, they convicted the US of waging an illegal war of aggression against Vietnam, of war crimes and, most sensationally, of ‘genocide against the people of Vietnam’.

Then, nothing much happened. The verdicts were welcomed by those who were already convinced of America’s immorality in Indochina and mocked by everyone else, before being forgotten entirely. Even though the American public’s mood eventually soured on the war, the Russell Tribunal had little to do with it. Today, its main legacy lies in the numerous copycat tribunals it has inspired, staffed by cranks, convened in cavernous public buildings, rendering verdicts that, just like the Russell Tribunal’s condemnations of US policy in Vietnam, were never in doubt.

As Clive Webb candidly admits in Vietdamned: How the World’s Greatest Minds Put America on Trial, posterity has been unkind not only to the Tribunal, but to the force behind it.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Demis Hassabis: Accelerating Scientific Discovery with AI

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

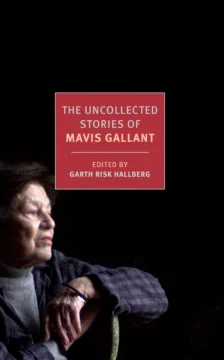

The Uncollected Stories of Mavis Gallant

Tessa Hadley at the LRB:

It isn’t necessarily a good thing when a publisher brings out a writer’s uncollected stories. More is sometimes less. Barrels are scraped, doubts – often the writer’s own, if she or he is no longer around – are set aside; these stories may not have been collected for good reason, and reading someone’s weaker attempts can dilute the power of the rest. The failures give away the writer’s workings – the swan’s feet paddling hard under the assured surface – which can be disenchanting, at least temporarily. There’s no such problem, however, with this thick volume of Mavis Gallant’s Uncollected Stories, which brings together everything left out of the various collections and selections published over the last thirty years. There are 44 stories here and hardly any duds or clumsy landings. (Apparently – wise woman – Gallant threw a lot of work in the waste basket in ‘shreds’.) Each is so good that you have to pace yourself, recalling Gallant’s own admonition in her introduction to the Everyman edition of her Collected Stories: ‘Stories are not chapters of novels. They should not be read one after another, as if they were meant to follow along. Read one. Shut the book. Read something else. Come back later. Stories can wait.’ She’s right, but it’s easy for her to say. Temptation lies in wait for the unwary reader in every beginning of a new story.

It isn’t necessarily a good thing when a publisher brings out a writer’s uncollected stories. More is sometimes less. Barrels are scraped, doubts – often the writer’s own, if she or he is no longer around – are set aside; these stories may not have been collected for good reason, and reading someone’s weaker attempts can dilute the power of the rest. The failures give away the writer’s workings – the swan’s feet paddling hard under the assured surface – which can be disenchanting, at least temporarily. There’s no such problem, however, with this thick volume of Mavis Gallant’s Uncollected Stories, which brings together everything left out of the various collections and selections published over the last thirty years. There are 44 stories here and hardly any duds or clumsy landings. (Apparently – wise woman – Gallant threw a lot of work in the waste basket in ‘shreds’.) Each is so good that you have to pace yourself, recalling Gallant’s own admonition in her introduction to the Everyman edition of her Collected Stories: ‘Stories are not chapters of novels. They should not be read one after another, as if they were meant to follow along. Read one. Shut the book. Read something else. Come back later. Stories can wait.’ She’s right, but it’s easy for her to say. Temptation lies in wait for the unwary reader in every beginning of a new story.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How a century of US immigration law has evaded constitutional rights

Debbie Nathan in the Boston Review:

What happened to former Columbia University student and Palestine rights activist Mahmoud Khalil has rightly alarmed many indignant Americans. Some have sought reassurance in the idea that since his abduction is nakedly unconstitutional, the institutions of American democracy—the Constitution, rule of law, brakes on the unchecked use of power—will swoop in to put an end to the madness. After all, we have the vaunted First Amendment. Attorneys from the ACLU and Center for Constitutional Rights are representing Khalil; surely their free speech arguments will impel his freedom and cancel his deportation. His detention surely is just one more instance of Trumpian insanity. Surely it will prove legally frivolous.

What happened to former Columbia University student and Palestine rights activist Mahmoud Khalil has rightly alarmed many indignant Americans. Some have sought reassurance in the idea that since his abduction is nakedly unconstitutional, the institutions of American democracy—the Constitution, rule of law, brakes on the unchecked use of power—will swoop in to put an end to the madness. After all, we have the vaunted First Amendment. Attorneys from the ACLU and Center for Constitutional Rights are representing Khalil; surely their free speech arguments will impel his freedom and cancel his deportation. His detention surely is just one more instance of Trumpian insanity. Surely it will prove legally frivolous.

But it’s too soon to be sure, thanks to over a century of federal law that has hogtied the judiciary—and most dramatically, the Supreme Court—when it comes to judges’ ability to rule on the constitutionality of immigration rules. Yes, the First Amendment offers speech protections. But we also have a lesser-known idea that has influenced congressional and executive branch–mandated immigration law for well over a century: the plenary power doctrine. According to the doctrine’s principles, judges should avoid ruling on whether or not immigration laws are constitutional, even when it appears they are not.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

Being-towards-death

All dressed up

And nowhere to go

Veiled eyes

Sealed lips

Fettered feet

Moved

Here, there

Against my will

Liberate me, Death

Let another be born free

by Anjum Altaf

—transcreation, 3/22/25 of

an Urdu Poem by Sara Shagufta

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Many artists hope to create work that prompts conversation. The creators of the hit TV show “Adolescence,” about a boy who fatally stabs his female classmate, actually have.

Many artists hope to create work that prompts conversation. The creators of the hit TV show “Adolescence,” about a boy who fatally stabs his female classmate, actually have.