Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Drugstore Cowboy: Higher Powers

Jon Raymond at The Current:

“The Northwest’s Odyssey”—that’s what the great Puget Sound–born writer Charles D’Ambrosio once called Ken Kesey’s 1964 novel Sometimes a Great Notion. What he meant by that, I think, was that Kesey’s swaggering tale of an antiunion logging family, the Stampers, stands as epic and originary, and possibly the ultimate reference point for any literature written in this region ever after. The book, like the landscape it describes, is a volcanic performance, a thing of great wildness and riverine digression. Charlie was also implying, truthfully enough, that the written word doesn’t go back very far in these parts. He was saying that our most ancient writings are only about three or four generations old.

“The Northwest’s Odyssey”—that’s what the great Puget Sound–born writer Charles D’Ambrosio once called Ken Kesey’s 1964 novel Sometimes a Great Notion. What he meant by that, I think, was that Kesey’s swaggering tale of an antiunion logging family, the Stampers, stands as epic and originary, and possibly the ultimate reference point for any literature written in this region ever after. The book, like the landscape it describes, is a volcanic performance, a thing of great wildness and riverine digression. Charlie was also implying, truthfully enough, that the written word doesn’t go back very far in these parts. He was saying that our most ancient writings are only about three or four generations old.

By this way of thinking, one could argue that Drugstore Cowboy, the 1989 film directed by Portland, Oregon’s own Gus Van Sant, is our New Testament. Unlike Kesey’s novel, with its heroic, Homeric map of the territory, Drugstore Cowboy is a small, moral tale of mercy and transcendence, built on the suffering of a man whose faith is tempted by the tender flesh.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Two New Takes on Joni Mitchell

Leah Greenblatt at the NYT:

On one of her signature songs, the restless, almost phosphorescent 1976 anthem “Hejira,” Joni Mitchell sits in some cafe, sketching out a life philosophy: “We all come and go unknown/Each so deep and superficial/Between the forceps and the stone.” She sounds majestic but weary, like an eagle or an off-duty Valkyrie. Who are we flightless birds to disagree?

On one of her signature songs, the restless, almost phosphorescent 1976 anthem “Hejira,” Joni Mitchell sits in some cafe, sketching out a life philosophy: “We all come and go unknown/Each so deep and superficial/Between the forceps and the stone.” She sounds majestic but weary, like an eagle or an off-duty Valkyrie. Who are we flightless birds to disagree?

And yet: Such is the enduring lure of Joni-ology, the secular religion of her fandom, that two new meditations on Mitchell have already landed in this youngish year, just over a month apart. Henry Alford’s “I Dream of Joni” and Paul Lisicky’s “Song So Wild and Blue” are not really traditional works of scholarship or biography; footnotes are wielded gently. Instead, Mitchell mostly serves as a mirror and a muse, a blond godhead on which to pin the authors’ respective forms and fascinations.

With a title as pun-perfect as “I Dream of Joni,” you almost can’t blame Alford, the puckish longtime New Yorker writer and humorist, for writing an entire book to justify it.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Virtual reality rewrites rules of the swarm

From Science:

Among the most spectacular phenomena in nature is the sight of millions of desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria) juveniles marching together, flowing like a river through the arid habitat of North Africa and consuming vegetation as they go before molting to become devastating swarms of winged adults. Understanding how and why locusts exhibit aligned collective motion is vital for predicting and managing outbreaks. However, present knowledge of the rules that govern the emergence of such complex, patterned behavior and decision-making is based on a handful of theoretical models that recapitulate only some aspects of the observed behavioral patterns. On page 995 of this issue, Sayin et al. (1) describe the integration of field, laboratory, and virtual reality studies to show that prevailing models for explaining collective motion in locusts, and perhaps other systems as well, require revision.

Among the most spectacular phenomena in nature is the sight of millions of desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria) juveniles marching together, flowing like a river through the arid habitat of North Africa and consuming vegetation as they go before molting to become devastating swarms of winged adults. Understanding how and why locusts exhibit aligned collective motion is vital for predicting and managing outbreaks. However, present knowledge of the rules that govern the emergence of such complex, patterned behavior and decision-making is based on a handful of theoretical models that recapitulate only some aspects of the observed behavioral patterns. On page 995 of this issue, Sayin et al. (1) describe the integration of field, laboratory, and virtual reality studies to show that prevailing models for explaining collective motion in locusts, and perhaps other systems as well, require revision.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

The Great Watchers

Think of those great watchers of the sky,

the shepherds, the magi, how they looked

for a thousand years and saw there was order,

who learned not only Light would return,

but the moment she’d start her journey.

No writing then. The see-ers gave

what they knew to the song-makers —

the dreamy sons, the daughters who hummed

as they spun, the priestly keepers of story —

and the clever-handed heard, nodded

and turned poems into New Grange,

Stonehenge, The Great Temple of Karnak.

by Nils Peterson

from Loving Darkness a Little

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Famous Malcolm X speech “Any means necessary”

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2025 theme of “African Americans and Labor” throughout the month of February)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, February 27, 2025

Though natural selection favours self-interest, humans are extraordinarily good at cooperating with one another. Why?

Saira Khan at Aeon:

Every week at the office, you and your fellow employees have meetings to discuss progress on group projects and to divide tasks efficiently. Perhaps in the evening, you go home and cook dinner with your partner. At least once in your life, you might have seen a team of firefighters work together to extinguish a fire at a burning house and rescue those inside. You have probably also witnessed or participated in political demonstrations aimed at bettering the treatment of those in need. These are all examples of human cooperation toward a mutually beneficial end. Some of them seem so commonplace that we rarely think of them as anything special. Yet they are. It is not obvious that any of the other great ape species cooperate in such a way – spontaneously and with individuals they have never before met. Though there has been some evidence of cooperation in other great apes, the interpretation of studies on ape cooperation has also been contested. In the human case, cooperation is unequivocal.

Every week at the office, you and your fellow employees have meetings to discuss progress on group projects and to divide tasks efficiently. Perhaps in the evening, you go home and cook dinner with your partner. At least once in your life, you might have seen a team of firefighters work together to extinguish a fire at a burning house and rescue those inside. You have probably also witnessed or participated in political demonstrations aimed at bettering the treatment of those in need. These are all examples of human cooperation toward a mutually beneficial end. Some of them seem so commonplace that we rarely think of them as anything special. Yet they are. It is not obvious that any of the other great ape species cooperate in such a way – spontaneously and with individuals they have never before met. Though there has been some evidence of cooperation in other great apes, the interpretation of studies on ape cooperation has also been contested. In the human case, cooperation is unequivocal.

The evolution of cooperation has been of interest to biologists, philosophers and anthropologists for centuries. If natural selection favours self-interest, why would we cooperate at an apparent cost to ourselves?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A History Of Violence

Jamie Hood at Bookforum:

IN A 2019 INTERVIEW with Lauren Elkin, the writer Virginie Despentes remarked of #MeToo that something was missing from the movement, “disconcerting” stories that didn’t fit into an increasingly streamlined regime of victimhood: “I want to see an uprising of loose women,” she said. “It’s really important to give voice to people practicing a sexuality that isn’t quite—correct.” Despentes broke onto the scene with 1993’s notorious Baise-moi (Fuck Me in English, though some markets have translated the title as Rape Me instead), an unhinged fever dream of a novel following two women—one a prostitute, the other the survivor of a gang rape loosely based on Despentes’s own—on a robbery, fucking, and killing spree. The movie, when Despentes adapted it with filmmaker and porn actress Coralie Trinh Thi in 2000, was the first to be banned in France in twenty-eight years. In response to accusations that the film wasn’t art but pornography, Trinh Thi scoffed that it couldn’t possibly be porn—it wasn’t produced “for masturbation.”

IN A 2019 INTERVIEW with Lauren Elkin, the writer Virginie Despentes remarked of #MeToo that something was missing from the movement, “disconcerting” stories that didn’t fit into an increasingly streamlined regime of victimhood: “I want to see an uprising of loose women,” she said. “It’s really important to give voice to people practicing a sexuality that isn’t quite—correct.” Despentes broke onto the scene with 1993’s notorious Baise-moi (Fuck Me in English, though some markets have translated the title as Rape Me instead), an unhinged fever dream of a novel following two women—one a prostitute, the other the survivor of a gang rape loosely based on Despentes’s own—on a robbery, fucking, and killing spree. The movie, when Despentes adapted it with filmmaker and porn actress Coralie Trinh Thi in 2000, was the first to be banned in France in twenty-eight years. In response to accusations that the film wasn’t art but pornography, Trinh Thi scoffed that it couldn’t possibly be porn—it wasn’t produced “for masturbation.”

The protagonists of the novel, Nadine and Manu, react to their sexual and economic victimization not with shame or paralysis, but with a shocking torrent of morally unassimilable desire and force.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Handoff to Bots

Kevin Kelly at The Technium:

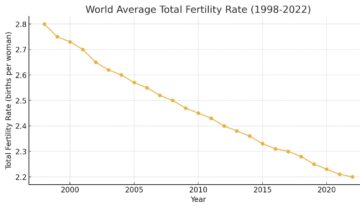

Human populations will start to decrease globally in a few more decades. Thereafter fewer and few humans will be alive to contribute labor and to consume what is made. However at the same historical moment as this decrease, we are creating millions of AIs and robots and agents, who could potentially not only generate new and old things, but also consume them as well, and to continue to grow the economy in a new and different way. This is a Economic Handoff, from those who are born to those who are made.

Human populations will start to decrease globally in a few more decades. Thereafter fewer and few humans will be alive to contribute labor and to consume what is made. However at the same historical moment as this decrease, we are creating millions of AIs and robots and agents, who could potentially not only generate new and old things, but also consume them as well, and to continue to grow the economy in a new and different way. This is a Economic Handoff, from those who are born to those who are made.

It has been nearly a thousand years since we last saw the total number of humans on this planet decrease year by year. For nearly a millennium we have lived with growing populations, and faster rates of growth. But in the coming decades, for the first time in a thousand years, the number of deaths on the planet each year will exceed the number of births.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Are Atoms Conscious?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sabine Hossenfelder: Another crazy week in AI development

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Jesus Is A Mushroom

John Last at The Long Now:

John Marco Allegro thought he had found a secret key. The problem was, no one would believe him.

In 01953, Allegro had been invited to the dusty shores of the Dead Sea to evaluate a newly unearthed trove of long-lost sacred documents — part of a team of respected British archaeologists brought to decipher one the greatest historical discoveries of the 20th century. The scrolls found there in the caves of Qumran had revealed a missing link in the evolution of Jewish spirituality, a rare and never-before-seen glimpse into the ancient world.

Allegro was soon assigned the work of translating a copper scroll that detailed the location of a vast treasure horde. But it was another hidden treasure that occupied his mind. Returning to Britain to study the documents in detail, he began constructing an elaborate theory based on hidden meanings he thought these ancient scrolls contained — a theory that would upend the entirety of sacred history.

Jesus, he believed, was a mushroom.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This

Fintan O’Toole in the New York Times:

In the novel, El Akkad disturbs his readers by projecting America’s present into a terrifying vision of what their familiar homeland might look like many decades hence. Here, he seeks to discomfit us by doing the opposite — asking us to look back on the present from an imagined future: “One day it will be considered unacceptable, in the polite liberal circles of the West, not to acknowledge all the innocent people killed in that long-ago unpleasantness. … One day the social currency of liberalism will accept as legal tender the suffering of those they previously smothered in silence.”

In the novel, El Akkad disturbs his readers by projecting America’s present into a terrifying vision of what their familiar homeland might look like many decades hence. Here, he seeks to discomfit us by doing the opposite — asking us to look back on the present from an imagined future: “One day it will be considered unacceptable, in the polite liberal circles of the West, not to acknowledge all the innocent people killed in that long-ago unpleasantness. … One day the social currency of liberalism will accept as legal tender the suffering of those they previously smothered in silence.”

Yet El Akkad himself is struggling against silence — not the taciturnity of indifference or cowardice but the near muteness imposed by the inadequacy of language in the face of mass obliteration. “One Day” reminded me of Samuel Beckett’s statement about having “no power to express … together with the obligation to express.” Whatever one thinks of its arguments, the book has the desperate vitality of a writer trying to wrench from mere words some adequate answer to his own question: “What is left to say but more dead, more dead?”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

Icy Mountains Constantly Walking

—for Seamus Heaney

Work took me to Ireland

……….. a twelve-hour flight.

The river Liffy;

……….. ale in a bar,

So many stories

……….. of passions and wars—

A hilltop stone tomb

……….. with the wind across the door.

Peat swamps go by:

……….. people of the ice age.

Endless fields and farms—

……….. the last two thousand years.

I read my poems in Galway,

……….. just the chirp of a bug.

And flew home thinking

……….. of literature and time.

The rows of books

……….. in the long hall at Trinity

The ranks of stony ranges

……….. above the ice of Greenland.

by Gary Snyder

from danger on peaks

Shoemaker Hoard, 2004

………..

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Rage Against the Machine

Andrew Cockburn in Harper’s Magazine:

Five months after Donald Trump moved into the White House in 2017, a reporter asked Vladimir Putin about the allegations that Russia had interfered in U.S. elections. After all, Trump had proclaimed that it would “be nice if we got along with Russia” during his campaign, and members of the Duma had greeted his victory with champagne toasts. But Putin quickly brushed the notion aside. There would be no point. Though American presidents come and go, he said, nothing ever really changes: “Do you know why? Because of the powerful bureaucracy. When a person is elected, they may have some ideas. Then people with briefcases arrive, well dressed, wearing dark suits, just like mine except for the red tie, since they wear black or dark-blue ones. These people start explaining how things are done. And instantly everything changes. This is what happens with every administration.”

Five months after Donald Trump moved into the White House in 2017, a reporter asked Vladimir Putin about the allegations that Russia had interfered in U.S. elections. After all, Trump had proclaimed that it would “be nice if we got along with Russia” during his campaign, and members of the Duma had greeted his victory with champagne toasts. But Putin quickly brushed the notion aside. There would be no point. Though American presidents come and go, he said, nothing ever really changes: “Do you know why? Because of the powerful bureaucracy. When a person is elected, they may have some ideas. Then people with briefcases arrive, well dressed, wearing dark suits, just like mine except for the red tie, since they wear black or dark-blue ones. These people start explaining how things are done. And instantly everything changes. This is what happens with every administration.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

#SayHerName

Brown and Ray in Brookings.Org:

“Today is a good day to arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor.” This phrase started as a call for the Kentucky Attorney General’s Office to hold accountable the officers that shot and killed the 26-year-old Louisville resident in her home in March 2020. In the months after Taylor’s killing, social media influencers and celebrities adopted the phrase to draw attention to her death as a way to disrupt the picturesque and cavalier digital culture of platforms like Instagram and Tik Tok. Oprah Winfrey even gave up her coveted spot on the cover of O Magazine by putting a picture of Taylor, an emergency medical technician, on the cover. Winfrey also placed billboards around the city of Louisville (one of which were vandalized) to demand the arrest of the officers involved.

“Today is a good day to arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor.” This phrase started as a call for the Kentucky Attorney General’s Office to hold accountable the officers that shot and killed the 26-year-old Louisville resident in her home in March 2020. In the months after Taylor’s killing, social media influencers and celebrities adopted the phrase to draw attention to her death as a way to disrupt the picturesque and cavalier digital culture of platforms like Instagram and Tik Tok. Oprah Winfrey even gave up her coveted spot on the cover of O Magazine by putting a picture of Taylor, an emergency medical technician, on the cover. Winfrey also placed billboards around the city of Louisville (one of which were vandalized) to demand the arrest of the officers involved.

For a moment, this attention seemed to bring attention to Breonna and by extension Black women who are victims of police brutality.

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2025 theme of “African Americans and Labor” throughout the month of February)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, February 26, 2025

Stanley Fish’s Cinematic Jurisprudence

Julie Stone Peters in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

Feisty contrarian Stanley Fish has served us for decades as the public intellectual people love to hate. Feminist social critic Camille Paglia famously described him as “a totalitarian Tinkerbell.” Marxist literary theorist Terry Eagleton said he was “the Donald Trump of American academia, a brash, noisy entrepreneur of the intellect who pushes his ideas in the conceptual marketplace with all the fervour with which others peddle second-hand Hoovers.” A brilliant scholar of late medieval and Renaissance poetry, he came to prominence in the 1980s for his claim that “interpretive communities” determine how you interpret a text—a theory that offered liberal legal scholars an alternative to the rigid originalism and textualism of the conservative Rehnquist Supreme Court. Teaching at prestigious law schools (while secretly working toward a night school law degree), he began writing for public venues. The New York Times eventually gave him a syndicated column, where he opined on everything from the decline of the humanities to Hillary-hating and stepping on Jesus (on a scrap of paper). Both on lecture tours and in print, he has fought with all comers: conservative justice Antonin Scalia, liberal rights theorists Ronald Dworkin and Martha Nussbaum, radical law professor Duncan Kennedy.

Feisty contrarian Stanley Fish has served us for decades as the public intellectual people love to hate. Feminist social critic Camille Paglia famously described him as “a totalitarian Tinkerbell.” Marxist literary theorist Terry Eagleton said he was “the Donald Trump of American academia, a brash, noisy entrepreneur of the intellect who pushes his ideas in the conceptual marketplace with all the fervour with which others peddle second-hand Hoovers.” A brilliant scholar of late medieval and Renaissance poetry, he came to prominence in the 1980s for his claim that “interpretive communities” determine how you interpret a text—a theory that offered liberal legal scholars an alternative to the rigid originalism and textualism of the conservative Rehnquist Supreme Court. Teaching at prestigious law schools (while secretly working toward a night school law degree), he began writing for public venues. The New York Times eventually gave him a syndicated column, where he opined on everything from the decline of the humanities to Hillary-hating and stepping on Jesus (on a scrap of paper). Both on lecture tours and in print, he has fought with all comers: conservative justice Antonin Scalia, liberal rights theorists Ronald Dworkin and Martha Nussbaum, radical law professor Duncan Kennedy.

At age 86, Fish is still at it. A heretic of the left, he still loves pillorying liberal pieties.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

World Nature Photography Awards 2025

More here.

Kenneth Roth on the Fight for Human Rights

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Why I Am Not A Conflict Theorist

Scott Alexander at Astral Codex Ten:

Conflict theory is the belief that political disagreements come from material conflict. So for example, if rich people support capitalism, and poor people support socialism, this isn’t because one side doesn’t understand economics. It’s because rich people correctly believe capitalism is good for the rich, and poor people correctly believe socialism is good for the poor. Or if white people are racist, it’s not because they have some kind of mistaken stereotypes that need to be corrected – it’s because they correctly believe racism is good for white people.

Conflict theory is the belief that political disagreements come from material conflict. So for example, if rich people support capitalism, and poor people support socialism, this isn’t because one side doesn’t understand economics. It’s because rich people correctly believe capitalism is good for the rich, and poor people correctly believe socialism is good for the poor. Or if white people are racist, it’s not because they have some kind of mistaken stereotypes that need to be corrected – it’s because they correctly believe racism is good for white people.

Some people comment on my more political posts claiming that they’re useless. You can’t (they say) produce change by teaching people Economics 101 or the equivalent. Conflict theorists understand that nobody ever disagreed about Economics 101. Instead you should try to organize and galvanize your side, so they can win the conflict.

I think simple versions of conflict theory are clearly wrong. This doesn’t mean that simple versions of mistake theory (the idea that people disagree because of reasoning errors, like not understanding Economics 101) are automatically right. But it gives some leeway for thinking harder about how reasoning errors and other kinds of error interact.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.