Natalie Hammond at LitHub:

If you watch clips of his last appearance as Ziggy, at his infamous concert at the Hammersmith Odeon, you can see these rapid- fire changes in action. As Bowie starts “Ziggy Stardust,” he’s wearing a black diamond-shaped jumpsuit with shots of blue and red, his feet planted about a meter apart. Two pairs of hands materialize out of the darkness and deftly yank its sleeves, revealing the famously short white satin kimono, which is positively luminescent under the stage lights. He does the same thing again later with two more outfits by Kansai Yamamoto: the white cape revealing the marvelous, multicolored jumpsuit. At one point, Bowie goes offstage to change into his sculpted-shoulder two-piece, another number by Burretti, which he wears with the boots. You can tell how tight it is because he grimaces as it goes up his legs. He smooths out each of his sleeves so that they sit just so. He must have looked something like a red, blue, and silver mirage, a sensory assault on your eyes and ears that made them explode with color and sound. Exhilarating doesn’t even begin to describe it. This was nothing short of earth-shattering.

If you watch clips of his last appearance as Ziggy, at his infamous concert at the Hammersmith Odeon, you can see these rapid- fire changes in action. As Bowie starts “Ziggy Stardust,” he’s wearing a black diamond-shaped jumpsuit with shots of blue and red, his feet planted about a meter apart. Two pairs of hands materialize out of the darkness and deftly yank its sleeves, revealing the famously short white satin kimono, which is positively luminescent under the stage lights. He does the same thing again later with two more outfits by Kansai Yamamoto: the white cape revealing the marvelous, multicolored jumpsuit. At one point, Bowie goes offstage to change into his sculpted-shoulder two-piece, another number by Burretti, which he wears with the boots. You can tell how tight it is because he grimaces as it goes up his legs. He smooths out each of his sleeves so that they sit just so. He must have looked something like a red, blue, and silver mirage, a sensory assault on your eyes and ears that made them explode with color and sound. Exhilarating doesn’t even begin to describe it. This was nothing short of earth-shattering.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

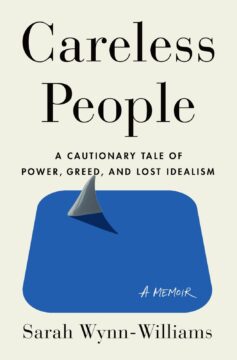

Meta’s governmental strategy and influence is now clearer than ever, thanks to Sarah Wynn Williams’s recently published memoir,

Meta’s governmental strategy and influence is now clearer than ever, thanks to Sarah Wynn Williams’s recently published memoir,  WIRED: In the late ’90s, when the internet began to spread, there was a discourse that this would bring about world peace. It was thought that with more information reaching more people, everyone would know the truth, mutual understanding would be born, and humanity would become wiser. WIRED, which has been a voice of change and hope in the digital age, was part of that thinking at the time. In your new book, Nexus, you write that such a view of information is too naive. Can you explain this?

WIRED: In the late ’90s, when the internet began to spread, there was a discourse that this would bring about world peace. It was thought that with more information reaching more people, everyone would know the truth, mutual understanding would be born, and humanity would become wiser. WIRED, which has been a voice of change and hope in the digital age, was part of that thinking at the time. In your new book, Nexus, you write that such a view of information is too naive. Can you explain this? O

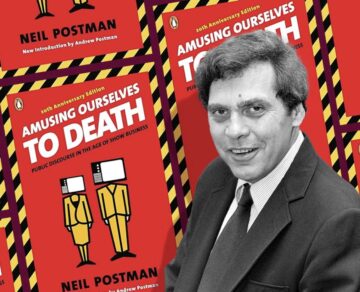

O Every so often an eye-opening work of social criticism becomes a surprise bestseller. In 1979, everyone was talking about Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism, and in 1987, it was Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind. Last year, Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation raised the alarm, encouraging readers outside the parenting-book world to consider what the teenage mental health crisis might mean for the culture at large. Typically the work of a professor with an aptitude for speaking to a general readership, this sort of book hits just as popular anxiety about a new technology or ideology—smartphones, the self-actualization movement, multiculturalism—is cresting. Ideas that may have been simmering away in academia suddenly burst into the common conversation. However, the very qualities that make these books feel tremendously relevant at a particular historical moment also tend to make them fade into obscurity when that moment passes. The blockbuster cultural criticism book tends to speak to its time—then become a curio as the culture changes around it.

Every so often an eye-opening work of social criticism becomes a surprise bestseller. In 1979, everyone was talking about Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism, and in 1987, it was Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind. Last year, Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation raised the alarm, encouraging readers outside the parenting-book world to consider what the teenage mental health crisis might mean for the culture at large. Typically the work of a professor with an aptitude for speaking to a general readership, this sort of book hits just as popular anxiety about a new technology or ideology—smartphones, the self-actualization movement, multiculturalism—is cresting. Ideas that may have been simmering away in academia suddenly burst into the common conversation. However, the very qualities that make these books feel tremendously relevant at a particular historical moment also tend to make them fade into obscurity when that moment passes. The blockbuster cultural criticism book tends to speak to its time—then become a curio as the culture changes around it. In all animals mating is a deal: one sex donates a few million sperm, the other a handful of eggs, the merger between which—unless a predator intervenes—will result in a brood of young. Win-win for the parents, genetically speaking. But there are few creatures that behave as if sex is a dull, simple or even mutually beneficial transaction and many that behave as if it is an event of transcendent emotional and aesthetic salience to be treated with reverence, suspicion, angst and quite a bit of violence.

In all animals mating is a deal: one sex donates a few million sperm, the other a handful of eggs, the merger between which—unless a predator intervenes—will result in a brood of young. Win-win for the parents, genetically speaking. But there are few creatures that behave as if sex is a dull, simple or even mutually beneficial transaction and many that behave as if it is an event of transcendent emotional and aesthetic salience to be treated with reverence, suspicion, angst and quite a bit of violence. With roughly

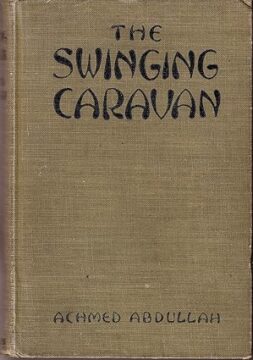

With roughly  ACHMED ABDULLAH was, during the early decades of the previous century, a playwright with successes on Broadway and the West End, an Oscar-nominated screenwriter, an author of dozens of books, and a writer of adventure and fantasy stories for the pulps, including Argosy, The All-Story, Munsey’s, and Blue Book. The gossip columns reported his comings and goings as a man about town.

ACHMED ABDULLAH was, during the early decades of the previous century, a playwright with successes on Broadway and the West End, an Oscar-nominated screenwriter, an author of dozens of books, and a writer of adventure and fantasy stories for the pulps, including Argosy, The All-Story, Munsey’s, and Blue Book. The gossip columns reported his comings and goings as a man about town. As Isaacson surveyed the landscape in search of a new genius, one name kept coming up: Elon Musk. He was, without a doubt, a man with grand vision — electric cars, space travel, telepathy. He was unyielding in this vision, too, sometimes belligerently so.

As Isaacson surveyed the landscape in search of a new genius, one name kept coming up: Elon Musk. He was, without a doubt, a man with grand vision — electric cars, space travel, telepathy. He was unyielding in this vision, too, sometimes belligerently so. I

I

The origins of Eid can be traced back to the time of the Prophet Muhammad in the 7th century. Eid al-Fitr, which translates to the “Festival of Breaking the Fast,” is celebrated at the end of Ramadan, the month of fasting. The significance of this festival lies in the completion of a month-long spiritual journey of self-discipline, reflection, and devotion to Allah. It is a time for Muslims to express gratitude for the strength and patience shown during Ramadan. The celebration of Eid al-Fitr is not only a personal milestone but also a communal event that reinforces the bonds of brotherhood and sisterhood among Muslims.

The origins of Eid can be traced back to the time of the Prophet Muhammad in the 7th century. Eid al-Fitr, which translates to the “Festival of Breaking the Fast,” is celebrated at the end of Ramadan, the month of fasting. The significance of this festival lies in the completion of a month-long spiritual journey of self-discipline, reflection, and devotion to Allah. It is a time for Muslims to express gratitude for the strength and patience shown during Ramadan. The celebration of Eid al-Fitr is not only a personal milestone but also a communal event that reinforces the bonds of brotherhood and sisterhood among Muslims.