Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Sunday Poem

Whispering Night

One clear night while the others slept, I climbed

the stairs to the roof of the house and under a sky

the rolling crests of it raked by the wind, becoming

like bits of lace tossed in the air. I stood in the long

whispering night, waiting for something, a sign, the approach

of a distant light, and I imagined you coming closer,

the dark waves of your hair mingling with the sea,

and the dark became desire, and desire the arriving light.

The nearness, the momentary warmth of you as I stood

on that lonely height watching the slow swells of the sea

break on the shore and turn briefly into glass and disappear…

Why did I believe you would come out of nowhere? Why with all

that the world offers would you come only because I was here?

by Mark Strand

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, April 11, 2025

A Penetrating New Book Celebrates Lennon and McCartney

T Bone Burnett in the New York Times:

In our culture, music is most often written about in terms of sales, streams and chart positions. That is, of course, the least intelligent way to think about or talk about music.

In our culture, music is most often written about in terms of sales, streams and chart positions. That is, of course, the least intelligent way to think about or talk about music.

Ian Leslie’s “John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs” is unconcerned with all that, but rather it explores the way two extraordinarily gifted young men combined and exchanged their gifts while inspiring, challenging, teaching and learning from each other.

In the great teams of composers before John Lennon and Paul McCartney — Rodgers and Hart, Lerner and Loewe, Leiber and Stoller, Bacharach and David — one of the members wrote the music and the other wrote the lyrics. John and Paul both wrote music and both wrote lyrics, and they made a decision at the beginning of their collaboration to share the credit on all of their compositions, thereby creating a third being called Lennon and McCartney. That selfless, generous merger, as their egos shape-shifted into and out of each other, unleashed a power that took music to a height that has not since been surpassed, or I think it safe to say, even reached.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

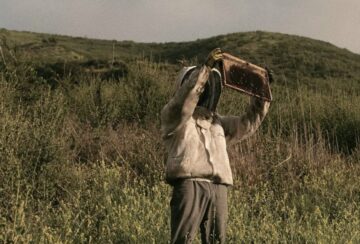

Telling the Bees

Emily Polk in Emergence:

I have loved bees my entire life, though my love for beekeepers started when I was writing a story for the Boston Globe about the dangers of mites to bee colonies in North America. I drove out to Hudson, a conservative town in rural New Hampshire, to meet leaders of the New Hampshire Beekeepers Association. I arrived just in time to watch a couple of senior bearded men in flannel shirts and Carhartt pants transport crates of bees into new hives. I was completely entranced by their delicacy and elegance. They seemed to be dancing. I wrote of one of the beekeepers, “He moves in a graceful rhythm … shaking the three-pound crate of bees into the hive, careful not to crush the queen, careful to make sure she has enough bees to tend to her, careful not to disturb or alarm them as he tenderly puts the frames back into the hive. And he does not get stung.” I was not expecting to find old men dancing with the grace of ballerinas under pine trees with a tenderness for the bees I wouldn’t have been able to imagine had I not witnessed it myself. This moment marked the beginning of my interest in what bees could teach us.

I have loved bees my entire life, though my love for beekeepers started when I was writing a story for the Boston Globe about the dangers of mites to bee colonies in North America. I drove out to Hudson, a conservative town in rural New Hampshire, to meet leaders of the New Hampshire Beekeepers Association. I arrived just in time to watch a couple of senior bearded men in flannel shirts and Carhartt pants transport crates of bees into new hives. I was completely entranced by their delicacy and elegance. They seemed to be dancing. I wrote of one of the beekeepers, “He moves in a graceful rhythm … shaking the three-pound crate of bees into the hive, careful not to crush the queen, careful to make sure she has enough bees to tend to her, careful not to disturb or alarm them as he tenderly puts the frames back into the hive. And he does not get stung.” I was not expecting to find old men dancing with the grace of ballerinas under pine trees with a tenderness for the bees I wouldn’t have been able to imagine had I not witnessed it myself. This moment marked the beginning of my interest in what bees could teach us.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The impact of AI | Nobel Prize Dialogue Tokyo 2025

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How Universities Can Save Themselves

Nils Gilman at Persuasion:

The question that leaders of research universities must grapple with is this: How can we preserve and enhance what is uniquely valuable about the research university? To do that, we must begin by defining what is “uniquely valuable”—that is, what research universities do better than any other existing institution, and without which society would suffer badly. I take those uniquely valuable attributes to be: (a) the creation of highly well-trained experts; (b) path-breaking knowledge creation; and, crucially, though often ignored or even denigrated, (c) knowledge preservation and transmission.

The question that leaders of research universities must grapple with is this: How can we preserve and enhance what is uniquely valuable about the research university? To do that, we must begin by defining what is “uniquely valuable”—that is, what research universities do better than any other existing institution, and without which society would suffer badly. I take those uniquely valuable attributes to be: (a) the creation of highly well-trained experts; (b) path-breaking knowledge creation; and, crucially, though often ignored or even denigrated, (c) knowledge preservation and transmission.

You will note that I do not list “remediation of historic wrongs” or “promotion of social justice” as among the unique value-adds of research universities. This is not because I do not regard these goals as worthwhile but rather because I do not regard those objectives as ones that research universities are “uniquely” suited to pursue. Those projects, I would argue, are much better implemented either through an explicit political process or through civil society actors with explicit moral missions such as churches, charities, and so on.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Ibn Sina (Avicenna) – The Greatest Muslim Philosopher?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Uses and Abuses of Manet’s Olympia

Todd Cronan at nonsite:

When Édouard Manet exhibited Olympia in the Salon of 1865, it unleashed a firestorm. Viewers were shocked by the subject matter—the sheer nakedness of the sitter—and by his formal treatment of the subject: critics lamented the lack of finish, the sharp contrast between light and dark, and, above all, the starkness of the model’s outward look at the viewer. For critics at the time, Manet’s shocking way with form went hand in hand with a sense of moral outrage, around gender and class. Olympia subtly but powerfully broke all the unspoken rules about the nude in painting and set the standard for a new form of revolutionary modern art.

When Édouard Manet exhibited Olympia in the Salon of 1865, it unleashed a firestorm. Viewers were shocked by the subject matter—the sheer nakedness of the sitter—and by his formal treatment of the subject: critics lamented the lack of finish, the sharp contrast between light and dark, and, above all, the starkness of the model’s outward look at the viewer. For critics at the time, Manet’s shocking way with form went hand in hand with a sense of moral outrage, around gender and class. Olympia subtly but powerfully broke all the unspoken rules about the nude in painting and set the standard for a new form of revolutionary modern art.

Olympia has been subject to countless interpretations for over a century, but one subject has seemingly eluded critical commentary: race. If the white model Victorine Meurent has been at the center of many interpretations, what about the other, equally central character, the model’s black maid, Laure (we don’t know her last name).

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

Solitary Vireo

I understand why people drive around

with their stereos up and their windows down;

sometimes it’s not enough to burn alone

inside, you want everyone, the world,

to feel your heat, char their fingers

picking you out of the crowd.

But the guy who sells you a scratch ticket

drops your change on the counter

right next to your upturned palm,

and the clerk in the booth at the bank,

and the gas station, and the fast-food drive-thru,

shuts off her intercom before you can

tell her what you want—

maybe you’ll steal from her.

Maybe you take your white-hot ache,

turn it inside out, wave it, snap it

open like a toreador’s cape. Maybe for a while

you feel like a bullfighter—

except the bull won’t charge. So you go

to the park because you always go,

and while you’re there some old lady

grabs your arm and points:

Vireo, she says, vireo.

Jesus, you think, but you’re tired,

so take her binoculars and look, see

the startled round eye of a bird,

its chest pushing out notes,

You’re still looking

while the woman reads to you from her book:

A common migrant in most of the East.

Loud song of short, varied phrases repeat

See-me, hear me, here-I-am.

by Amy Dryansky

from How I Got Lost So Close to Home

Alice James Books, 1999

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Almodóvar’s Women

Alana Pockros at The Point:

If you are a leading woman in a Pedro Almodóvar film, your life will not be frictionless. You will have a terminal illness. Or if you don’t have one, you will be grieving the one that someone very close to you has. You will be a single mother or mother-to-be. You will have very intimate female friendships, but you won’t always be faithful, or act selflessly. You will work a creative career, such as writing or acting or photographing products for advertisements. You won’t care too much about traditional values even though your Catholic family or community does. You will smoke cigarettes and pop pills when you’re stressed. You might have paid a pretty penny for your breasts, or have been naturally endowed. You will be unconventionally, or maybe conventionally, beautiful, and always expressive. You will be middle-aged. You will have a romantic Castilian accent. You might be Penélope Cruz.

If you are a leading woman in a Pedro Almodóvar film, your life will not be frictionless. You will have a terminal illness. Or if you don’t have one, you will be grieving the one that someone very close to you has. You will be a single mother or mother-to-be. You will have very intimate female friendships, but you won’t always be faithful, or act selflessly. You will work a creative career, such as writing or acting or photographing products for advertisements. You won’t care too much about traditional values even though your Catholic family or community does. You will smoke cigarettes and pop pills when you’re stressed. You might have paid a pretty penny for your breasts, or have been naturally endowed. You will be unconventionally, or maybe conventionally, beautiful, and always expressive. You will be middle-aged. You will have a romantic Castilian accent. You might be Penélope Cruz.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How stress shapes cancer’s course

Diana Kwon in Knowable Magazine:

About two millennia ago, the Greek physicians Hippocrates and Galen suggested that melancholia — depression brought on by an excess of “black bile” in the body — contributed to cancer. Since then, scores of researchers have investigated the association between cancer and the mind, with some going as far as to suggest that some people have a cancer-prone or “Type C” personality.

About two millennia ago, the Greek physicians Hippocrates and Galen suggested that melancholia — depression brought on by an excess of “black bile” in the body — contributed to cancer. Since then, scores of researchers have investigated the association between cancer and the mind, with some going as far as to suggest that some people have a cancer-prone or “Type C” personality.

Most researchers now reject the idea of a cancer-prone personality. But they still haven’t settled what influence stress and other psychological factors can have on the onset and progression of cancer. More than a hundred epidemiological studies — some involving tens of thousands of people — have linked depression, low socioeconomic status and other sources of psychological stress to an increase in cancer risk, and to a worse prognosis for people who already have the disease. However, this literature is full of contradictions, especially in the first case.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Mukhtar Begum sings Agha Hashar Kashmiri’s Ghazal

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, April 10, 2025

“Story of a Murder” by Hallie Rubenhold – an engrossing retelling of “the crime of the century”

Anthony Quinn in The Guardian:

On the evening of 31 January 1910, two couples dined together at a house in Hilldrop Crescent, on the borders of Holloway, London. The hosts, Dr Crippen and his wife, Belle Elmore, had been entertaining their friends, Clara and Paul Martinetti, until the small hours. After some difficulty fetching a cab, the visitors headed home around 1.30am. It was the last time they, or anyone else, would see Elmore alive. When her colleagues at the Music Hall Ladies’ Guild made inquiries about their friend – she was treasurer of the organisation – Crippen told them she had gone off to America to deal with a family crisis. Some weeks later they were informed she had died of double pneumonia in Los Angeles.

On the evening of 31 January 1910, two couples dined together at a house in Hilldrop Crescent, on the borders of Holloway, London. The hosts, Dr Crippen and his wife, Belle Elmore, had been entertaining their friends, Clara and Paul Martinetti, until the small hours. After some difficulty fetching a cab, the visitors headed home around 1.30am. It was the last time they, or anyone else, would see Elmore alive. When her colleagues at the Music Hall Ladies’ Guild made inquiries about their friend – she was treasurer of the organisation – Crippen told them she had gone off to America to deal with a family crisis. Some weeks later they were informed she had died of double pneumonia in Los Angeles.

Thus was sparked an international murder case, one of the most notorious in Britain, later called “the crime of the century”. But Hallie Rubenhold’s engrossing account begins a generation earlier when Hawley Harvey Crippen, a homeopathic doctor, met and married a nurse, Charlotte Bell, in New York.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

There is now about five bottle caps worth of plastic in human brains

Nina Agrawal in the New York Times:

Dr. Garcia is part of a leading lab, run by toxicologist Matthew Campen, that is studying how tiny particles known as microplastics accumulate in our bodies. The researchers’ most recent paper, published in February in Nature Medicine, generated a string of alarmed headlines and buzz in the scientific community: They found that human brain samples from 2024 had nearly 50 percent more microplastics than brain samples from 2016.

Dr. Garcia is part of a leading lab, run by toxicologist Matthew Campen, that is studying how tiny particles known as microplastics accumulate in our bodies. The researchers’ most recent paper, published in February in Nature Medicine, generated a string of alarmed headlines and buzz in the scientific community: They found that human brain samples from 2024 had nearly 50 percent more microplastics than brain samples from 2016.

“This stuff is increasing in our world exponentially,” Dr. Campen said. As it piles up in the environment, it is piling up in us, too.

Some of the researchers’ other findings have also prompted widespread concern. In the study, the brains of people with dementia had far more microplastics than the brains of people without it.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Derek Muller Explains What Everyone Gets Wrong About AI and Learning

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Economists Say America’s Trade Deficits Are a Sign of Dominance Not Weakness

Paul Wiseman in Time:

Trump and his trade advisers insist that the rules governing global commerce put the United States at a distinct disadvantage. But mainstream economists—whose views Trump and his advisers disdain—say the president has a warped idea of world trade, especially a preoccupation with trade deficits, which they say do nothing to impede growth.

Trump and his trade advisers insist that the rules governing global commerce put the United States at a distinct disadvantage. But mainstream economists—whose views Trump and his advisers disdain—say the president has a warped idea of world trade, especially a preoccupation with trade deficits, which they say do nothing to impede growth.

The administration accuses other countries of erecting unfair trade barriers to keep out American exports and using underhanded tactics to promote their own. In Trump’s telling, his tariffs are a long-overdue reckoning: The U.S. is the victim of an economic mugging by Europe, China, Mexico, Japan and even Canada.

It’s true that some countries charge higher taxes on imports than the United States does. Some manipulate their currencies lower to ensure that their goods are price-competitive in international markets. Some governments lavish their industries with subsidies to give them an edge.

However, the United States is still the second-largest exporter in the world, after China.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The big idea: should you trust your gut?

Alex Curmi in The Guardian:

‘What should I do?” Whether openly stated or implicit, this is the question a new client usually raises in their first therapy session. People come to see me for many reasons: relationship problems, addiction and mental health difficulties, such as anxiety. Increasingly, I have found that beneath all of these disparate problems lies a common theme: indecision, the sense of feeling stuck, and lack of clarity as to the way forward.

‘What should I do?” Whether openly stated or implicit, this is the question a new client usually raises in their first therapy session. People come to see me for many reasons: relationship problems, addiction and mental health difficulties, such as anxiety. Increasingly, I have found that beneath all of these disparate problems lies a common theme: indecision, the sense of feeling stuck, and lack of clarity as to the way forward.

Making decisions is difficult. Anyone who has lain awake contemplating a romantic dilemma, or a sudden financial crisis, knows how hard it can be to choose a course of action. This is understandable, given that in any scenario we must contend with a myriad conflicting thoughts and emotions – painful recollections from the past, hopes for the future, and the expectations of family, friends, and co-workers.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

Instrument, 1865

The thick elms and cottonwood of the bluff still bore

the scars of battle that had raged in this place four

long years before. Trunks of trees had been stripped

of bark and splintered by cannon shot. Branches

had been torn from the canopy of maple above,

and their loss gave the trees an aspect both unbalanced

and misshapen. Six months before, at Centralia, he

vowed he would never surrender. But that had been in

some other reality, the reality of battle frenzy, where

the world falls away and there is only the awful and

exhilarating and terrifying present, which is like the

face of God, where creation meets destruction with

man as God’s instrument.

by Desmond Barry

from The Chivalry of Crime

Little Brown and Company, 2002

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A Protein Ratio Could Predict Alzheimer’s Disease Progression Decades in Advance

Sahana Sitaraman in The Scientist:

In 1906, a 50-year-old woman in Germany died of a mysterious illness. Before her death, she presented with a combination of symptoms that stumped doctors—progressive memory loss, paranoia, confusion, and aggression. A closer look into her brain post-mortem revealed abnormal clumps and tangled bundles of fibers. This was the first documented case of Alzheimer’s disease, described in detail by Alois Alzheimer, a clinical psychiatrist and neuroanatomist.1 His characterization of the disease pathology is still used for diagnosis of this neurodegenerative disorder. Scientists now know that the clumps are plaques formed by the protein fragment amyloid-beta (Aβ) and the tangles are abnormal accumulations of the protein tau within neurons.

In 1906, a 50-year-old woman in Germany died of a mysterious illness. Before her death, she presented with a combination of symptoms that stumped doctors—progressive memory loss, paranoia, confusion, and aggression. A closer look into her brain post-mortem revealed abnormal clumps and tangled bundles of fibers. This was the first documented case of Alzheimer’s disease, described in detail by Alois Alzheimer, a clinical psychiatrist and neuroanatomist.1 His characterization of the disease pathology is still used for diagnosis of this neurodegenerative disorder. Scientists now know that the clumps are plaques formed by the protein fragment amyloid-beta (Aβ) and the tangles are abnormal accumulations of the protein tau within neurons.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, April 9, 2025

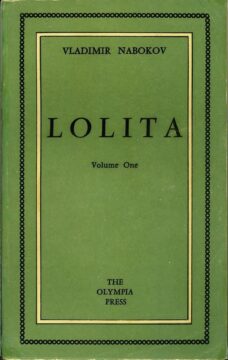

Claire Messud reads “Lolita” on its 70th anniversary

Claire Messud in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

At 70, Vladimir Nabokov’s most famous book, Lolita, is decidedly problematic. It is, after all, a novel narrated by a pedophile, kidnapper, and rapist (also, lest we forget, murderer) who tells his story from prison, who relates his crimes with a pyrotechnic verbal exhilaration that is tantamount to glee, who seduces each reader into complicity simply through the act of reading: to read the novel to the end is to have succumbed to Humbert Humbert’s insidious, sullying charms. Framed by the banal platitudes of John Ray Jr., the fictional psychologist whose foreword introduces the account (“‘Lolita’ should make all of us—parents, social workers, educators—apply ourselves with still greater vigilance and vision to the task of bringing up a better generation in a safer world”), Humbert’s exuberant voice seduces the reader, even as so many of the novel’s characters are foolishly, sometimes fatally, seduced. What are we doing, when we read this book with such pleasure? What was Nabokov doing, in writing this unsettling novel?

At 70, Vladimir Nabokov’s most famous book, Lolita, is decidedly problematic. It is, after all, a novel narrated by a pedophile, kidnapper, and rapist (also, lest we forget, murderer) who tells his story from prison, who relates his crimes with a pyrotechnic verbal exhilaration that is tantamount to glee, who seduces each reader into complicity simply through the act of reading: to read the novel to the end is to have succumbed to Humbert Humbert’s insidious, sullying charms. Framed by the banal platitudes of John Ray Jr., the fictional psychologist whose foreword introduces the account (“‘Lolita’ should make all of us—parents, social workers, educators—apply ourselves with still greater vigilance and vision to the task of bringing up a better generation in a safer world”), Humbert’s exuberant voice seduces the reader, even as so many of the novel’s characters are foolishly, sometimes fatally, seduced. What are we doing, when we read this book with such pleasure? What was Nabokov doing, in writing this unsettling novel?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.