Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

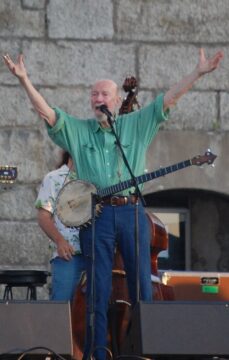

Pete Seeger in A Complete Unknown

Isle McElroy at The Believer:

Building a film around a temperamental genius is never as simple as placing a star at its center. Murphy and Chalamet both do their parts: they create, they scowl, they have affairs. They are misunderstood. But their perceived genius is less about their particular actions than it is about the reactions of secondary characters. This is apparent throughout A Complete Unknown. In her review of the film, Vulture’s Alison Willmore highlights the cast around Chalamet: “Its best sequences aren’t about Dylan so much as they are about what it was like to be in his orbit when it felt like he could remake the universe.” The film succeeds because it captures how Dylan’s peers saw him—what made them want to be near him, what made them want to support his career.

Building a film around a temperamental genius is never as simple as placing a star at its center. Murphy and Chalamet both do their parts: they create, they scowl, they have affairs. They are misunderstood. But their perceived genius is less about their particular actions than it is about the reactions of secondary characters. This is apparent throughout A Complete Unknown. In her review of the film, Vulture’s Alison Willmore highlights the cast around Chalamet: “Its best sequences aren’t about Dylan so much as they are about what it was like to be in his orbit when it felt like he could remake the universe.” The film succeeds because it captures how Dylan’s peers saw him—what made them want to be near him, what made them want to support his career.

This is recognizable in Edward Norton’s portrayal of the avuncular folk hero Pete Seeger. The two first interact in Woody Guthrie’s hospital room, when Dylan arrives late one evening to play a song he wrote for his ailing idol. As Dylan performs, the camera lingers on Seeger, his face quickly escalating past intrigue into admiration.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Esther Kinsky’s Lyrical Elegy for the Movies

Marek Makowski at The Millions:

In Kinsky’s latest novel, Seeing Further, the landscapes are still alive—but as the backdrop to the book’s main focus, the lost beauty and magic of cinema. Seeing Further is an elegy to the film-reel cinemas of the past, those places “that fomented stories by robbing you of words before the screen,” “these dormant motion-picture castles, with their worm-eaten, rusty, blockaded doors.” The question opening Seeing Further continues the preoccupations of Kinsky’s earlier fiction: “How to direct the gaze?” And Kinsky decides to turn her gaze to the abandoned ritual of cinema because, as her autobiographical narrator argues, “in the past century no location was as important for the how of seeing.” The narrator continues: “The collective experience facilitated by this space is disappearing along with it,” and so “this loss, whether mourned or not, deserves to be described and merits consideration.” Films and landscapes both point us to questions about the collective, to “the boundary between images seen and things experienced,” and Kinsky brings them into dialogue in strange and unexpected ways.

In Kinsky’s latest novel, Seeing Further, the landscapes are still alive—but as the backdrop to the book’s main focus, the lost beauty and magic of cinema. Seeing Further is an elegy to the film-reel cinemas of the past, those places “that fomented stories by robbing you of words before the screen,” “these dormant motion-picture castles, with their worm-eaten, rusty, blockaded doors.” The question opening Seeing Further continues the preoccupations of Kinsky’s earlier fiction: “How to direct the gaze?” And Kinsky decides to turn her gaze to the abandoned ritual of cinema because, as her autobiographical narrator argues, “in the past century no location was as important for the how of seeing.” The narrator continues: “The collective experience facilitated by this space is disappearing along with it,” and so “this loss, whether mourned or not, deserves to be described and merits consideration.” Films and landscapes both point us to questions about the collective, to “the boundary between images seen and things experienced,” and Kinsky brings them into dialogue in strange and unexpected ways.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

When ‘We’ Becomes ‘I’: The Case for Divorce

Alissa Bennett in the New York Times:

I can’t recall the first time I saw “The Misfits,” John Huston’s 1961 cinematic masterpiece about a quartet of mutually disenfranchised wanderers, but I’m certain it was after I’d become a divorcée. I know it wouldn’t have stuck with me so permanently otherwise. Set in Reno, Nev., a city once as famous for its hassle-free divorces as its casinos, the film is a timeless meditation on what it means to lose.

I can’t recall the first time I saw “The Misfits,” John Huston’s 1961 cinematic masterpiece about a quartet of mutually disenfranchised wanderers, but I’m certain it was after I’d become a divorcée. I know it wouldn’t have stuck with me so permanently otherwise. Set in Reno, Nev., a city once as famous for its hassle-free divorces as its casinos, the film is a timeless meditation on what it means to lose.

I was not yet 30 when my first marriage dissolved, by which point I’d seen several friends’ relationships likewise buckle beneath the looming specter of forever. It seemed that every few years there was a wave of these breakups, and I began to predict them like weather patterns. “It’s divorce season,” I’d say, and if time has mitigated the phenomenon in my own life, I wasn’t surprised to find confirmation that it still wreaks its havoc elsewhere.

In two new nonfiction books, the authors Scaachi Koul and Haley Mlotek find their inspiration in the emotional maelstrom that follows divorce. Reading them in parallel, I was reminded not only of how hard it is to stay together, but of how painful it is to try to recalibrate who you are when “we” suddenly becomes “I.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How to Make Superbabies

Gene Smith at Less Wrong:

Working in the field of genetics is a bizarre experience. No one seems to be interested in the most interesting applications of their research.

Working in the field of genetics is a bizarre experience. No one seems to be interested in the most interesting applications of their research.

We’ve spent the better part of the last two decades unravelling exactly how the human genome works and which specific letter changes in our DNA affect things like diabetes risk or college graduation rates. Our knowledge has advanced to the point where, if we had a safe and reliable means of modifying genes in embryos, we could literally create superbabies. Children that would live multiple decades longer than their non-engineered peers, have the raw intellectual horsepower to do Nobel prize worthy scientific research, and very rarely suffer from depression or other mental health disorders.

The scientific establishment, however, seems to not have gotten the memo. If you suggest we engineer the genes of future generations to make their lives better, they will often make some frightened noises, mention “ethical issues” without ever clarifying what they mean, or abruptly change the subject. It’s as if humanity invented electricity and decided the only interesting thing to do with it was make washing machines.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Stephen Asma: Embrace the Absurd

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

More thoughts on a great civilization, China, at its peak

Noah Smith at Noahpinion:

The 20th century had a bunch of rising powers that all reached their peaks in terms not just of relative military might and economic strength, but of technological and cultural innovation. These included the United States, Japan, Germany, and Russia. So far, the 21st century is a little different, because only one major civilization is hitting its peak right now: China. All the old powers are declining, and India is just beginning to hit its stride.

The 20th century had a bunch of rising powers that all reached their peaks in terms not just of relative military might and economic strength, but of technological and cultural innovation. These included the United States, Japan, Germany, and Russia. So far, the 21st century is a little different, because only one major civilization is hitting its peak right now: China. All the old powers are declining, and India is just beginning to hit its stride.

China’s peak is truly spectacular — a marvel of state capacity and resource mobilization never seen before on this planet. In just a few years, China built more high-speed rail than all other countries in the world combined. Its auto manufacturers are leapfrogging the developed world, seizing leadership in the EV industry of the future. China has produced so many solar panels and batteries that it has driven down the cost to be competitive with fossil fuels — a huge blow against climate change, despite all of China’s massive coal emissions, and a victory for global energy abundance.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Woolly mice designed to engineer mammoth-like elephants

Pallab Ghosh in BBC News:

Genetically engineered woolly mice could one day help populate the Arctic with hairy, genetically modified elephants and help stop the planet warming.

Genetically engineered woolly mice could one day help populate the Arctic with hairy, genetically modified elephants and help stop the planet warming.

Those are the startling claims being made by a US company that said on Tuesday it had created mice with “mammoth-like traits”. Colossal Biosciences’ eventual goal is to engineer mammoth-like creatures that could help stop arctic permafrost from melting.

Criticism has flooded in, including that engineering mammoth-like creatures is a big stretch from making mice hairier, as well as being unethical, and that the whole project is a publicity stunt. But the company says it has been misjudged and that the mouse is an important tool on the path to restoring Earth’s depleted nature.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Cell Therapy is Poised for Sweet Victory in Diabetes

Shelby Bradford in The Scientist:

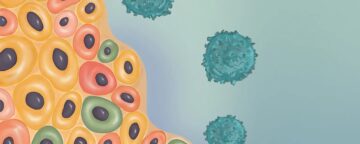

In 2024, a woman in China with type 1 diabetes (T1D) became the first person to have maintained independence from insulin for one year after receiving a transplantation of β cells derived from her own induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).1 This accomplishment—a huge step forward in cell therapy for diabetes—was the fruit of two decades of labor by Hongkui Deng, a stem cell biologist at Peking University. He and several other researchers who contributed to the advances in stem cell biology and transplantation science are beginning to see their dream of cell therapies for diabetes management become a reality.

In 2024, a woman in China with type 1 diabetes (T1D) became the first person to have maintained independence from insulin for one year after receiving a transplantation of β cells derived from her own induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).1 This accomplishment—a huge step forward in cell therapy for diabetes—was the fruit of two decades of labor by Hongkui Deng, a stem cell biologist at Peking University. He and several other researchers who contributed to the advances in stem cell biology and transplantation science are beginning to see their dream of cell therapies for diabetes management become a reality.

In T1D, the immune system attacks insulin-producing cells, β cell islets, in the pancreas, resulting in a gradual decline in the availability of insulin to regulate blood sugar.2 Dysregulated blood sugar can cause overproduction of ketones, leading to increased blood acidity, and an array of cardiovascular complications.3 “The only therapy we can really provide right now in clinical practice to manage diabetes is to provide [patients] with insulin therapy,” explained Melena Bellin, a pediatric endocrinologist at the University of Minnesota.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

Sus

Two pigs in a pickup sailing down the freeway

stomping with the sway,

……….. gaze back up the roadbed

………………….. on their last windy ride.

Big pink ears up ……. looking all around,

taut broad shoulders ……. trim little legs,

bright and lively with their parsnip-colored skin

wind-washed earth-diggers

……….. snuffling in the swamps

they’re not pork, they are forever Sus:

……….. breeze-braced and standing there,

…………………………………………… velvet-dusty pigs.

by Gary Snyder

from Danger on Peaks

Shoemaker Hoard Publishing, 2004

Sus— Urban dictionary: Giving the impression that

something is questionable or dishonest; suspicious.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

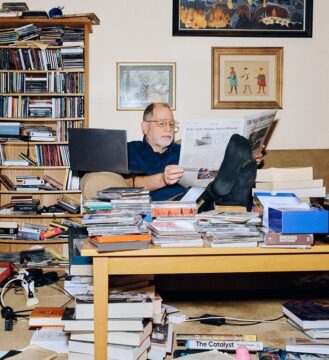

Tyler Cowen, the man who wants to know everything

John Phipps in The Economist:

At the end of the worst road on the impoverished Honduran island of Roatán lies Próspera, an aspiring libertarian city-state “designed for entrepreneurs to build better”. Last January Tyler Cowen, an economist at George Mason University in Virginia, found himself being ushered into an open-air co-working space beneath the attractive tropical chalet that serves as the city’s headquarters. A few digital nomads stood up to greet him, smoothing down their shorts. One of them began telling Cowen about the regulatory system in Próspera, which is partly autonomous from the Honduran government. Cowen listened politely, then looked out to where two brown birds were hovering above the shoreline. He asked what vultures were called on Roatán. Someone told him. “You use the Nahuatl word,” he replied admiringly.

At the end of the worst road on the impoverished Honduran island of Roatán lies Próspera, an aspiring libertarian city-state “designed for entrepreneurs to build better”. Last January Tyler Cowen, an economist at George Mason University in Virginia, found himself being ushered into an open-air co-working space beneath the attractive tropical chalet that serves as the city’s headquarters. A few digital nomads stood up to greet him, smoothing down their shorts. One of them began telling Cowen about the regulatory system in Próspera, which is partly autonomous from the Honduran government. Cowen listened politely, then looked out to where two brown birds were hovering above the shoreline. He asked what vultures were called on Roatán. Someone told him. “You use the Nahuatl word,” he replied admiringly.

Dressed in the same tatty blue jeans he’d been wearing all week, his libertarian beard trimmed to a grey muzzle, the 61-year-old appeared before these tanned utopians as a bright star in their intellectual firmament. Cowen’s blog, Marginal Revolution, is namechecked by billionaires; his books are sold in airports and read in Washington. His grant programmes have been backed by Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg and Peter Thiel.

Whether they know it or not, many tech gurus now subscribe to an economic analysis that Cowen first proposed in the 2010s, when he argued that technology could rescue America from a “great stagnation” that had been keeping its growth rates depressed for almost half a century. It was this argument, amplified by his relentless publication schedule, that helped find Cowen an audience in Silicon Valley and its downstream subcultures. Today, his readers are DOGE staffers.

Yet among acolytes, Cowen is famous not for a single theory but for the broad scope of his intellect. Put simply, he seems to know something about everything: machine learning, Icelandic sagas and where to eat in Bergen, Norway.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Physicist Working to Build Science-Literate AI

John Pavlus in Quanta:

He began studying machine learning, eventually fusing it with his doctoral research in astrophysics at Princeton University.

He began studying machine learning, eventually fusing it with his doctoral research in astrophysics at Princeton University.

Nearly a decade later, Cranmer (now at the University of Cambridge) has seen AI begin to transform science, but not nearly as much as he envisions. Single-purpose systems like AlphaFold can generate scientific predictions with revolutionary accuracy, but researchers still lack “foundation models” designed for general scientific discovery. These models would work more like a scientifically accurate version of ChatGPT, flexibly generating simulations and predictions across multiple research areas. In 2023, Cranmer and more than two dozen other scientists launched the Polymathic AI(opens a new tab) initiative to begin developing these foundation models.

The first step, Cranmer said, is equipping the model with the scientific skills that still elude most state-of-the-art AI systems.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Richard Dawkins and Steven Pinker Talk About Many Things

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The End of NATO, or The Sixth Impossible Thing

Adam Garfinkle at Quillette:

Reality can sometimes seem even stranger than fiction, and the second Trump administration has done what many people supposed to be six impossible things within the first month of its tenure. The upshot is that we are now living in a post-NATO world where black is white, up is down, friends are foes (and vice versa), and once-unthinkable impossibilities have become our new reality.

Reality can sometimes seem even stranger than fiction, and the second Trump administration has done what many people supposed to be six impossible things within the first month of its tenure. The upshot is that we are now living in a post-NATO world where black is white, up is down, friends are foes (and vice versa), and once-unthinkable impossibilities have become our new reality.

The first impossibility accomplished by the new administration saw Donald J. Trump and J.D. Vance win the only two elected offices of the US executive branch with a campaign of wild lies about the November 2020 election and what happened at the Capitol on 6 January 2021. After the inauguration, they turned those lies into loyalty tests required of nominees to plum jobs in the administration, including on the National Security Council staff and the Policy Planning staff at the State Department.

Second, on his first day in office, the president used his pardon power to release a loyal and violence-prone cohort of 1,600 insurrectionists.

Third, the White House won Senate confirmation of manifestly unsuitable nominees to head executive-branch departments and agencies, many of whom are openly hostile to the stolidly apolitical missions of their own offices.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A Conversation with Anne Carson

Anne Carson interviewed at the Paris Review:

When people ask me, “How are Canadians different from Americans?” I say, “Canadians have one characteristic: they’re polite, but wrong.” All the time, polite but wrong.

When people ask me, “How are Canadians different from Americans?” I say, “Canadians have one characteristic: they’re polite, but wrong.” All the time, polite but wrong.

“Wrong” I put in the title because, well, because of the Canadian thing. And also, something you always feel in academic life is that you’re wrong or on the verge of being wrong and you have to worry about that, because everything is so judgmental and hierarchical. Getting tenure depends on XYZ being “not wrong” every time you speak. So it’s kind of a mentality I was interested in disabling.

It’s something Simone Weil says in an essay she has about contradiction, because people find contradiction in philosophical texts so perplexing, and she specializes in contradiction. She says it’s a useful mental event, because it loosens the mind. And once you can loosen, you can go on to think other things or wider things or the things underneath where you were. It’s just suddenly a different landscape. And that loosening, I think, is what wrongness allows in.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Anne Carson: Beware…

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Government Knows A.G.I. is Coming

Ezra Klein at the NYT:

For the last couple of months, I have had this strange experience: Person after person — from artificial intelligence labs, from government — has been coming to me saying: It’s really about to happen. We’re about to get to artificial general intelligence.

For the last couple of months, I have had this strange experience: Person after person — from artificial intelligence labs, from government — has been coming to me saying: It’s really about to happen. We’re about to get to artificial general intelligence.

What they mean is that they have believed, for a long time, that we are on a path to creating transformational artificial intelligence capable of doing basically anything a human being could do behind a computer — but better. They thought it would take somewhere from five to 15 years to develop. But now they believe it’s coming in two to three years, during Donald Trump’s second term. They believe it because of the products they’re releasing right now and what they’re seeing inside the places they work. And I think they’re right.

If you’ve been telling yourself this isn’t coming, I really think you need to question that. It’s not web3. It’s not vaporware. A lot of what we’re talking about is already here, right now.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Painter of Thought: On Montaigne’s epistemic style

Jared Pollen in The Point:

Michel de Montaigne is often upheld as a model of the examined life. In her introduction to What Do I Know? (the latest selection of Montaigne’s essays, translated by David Coward and published in 2023 by Pushkin Press), Yiyun Li writes: “For me, his writing serves as a reminder, a prompt, even, a mandate: a regular meditation on selfhood, like daily yoga, is a healthy habit.” And in M.A. Screech’s introduction to his translation of the Essays, he describes it as “one of Europe’s great bedside books.” Alain de Botton likewise included Montaigne in his book The Consolations of Philosophy as a helpful guide for thinking about the problem of self-esteem, and in his book The School of Life, he writes that the Essays “amounted to a practical compendium of advice on helping us to know our fickle minds, find purpose, connect meaningfully with others and achieve intervals of composure and acceptance.”

Michel de Montaigne is often upheld as a model of the examined life. In her introduction to What Do I Know? (the latest selection of Montaigne’s essays, translated by David Coward and published in 2023 by Pushkin Press), Yiyun Li writes: “For me, his writing serves as a reminder, a prompt, even, a mandate: a regular meditation on selfhood, like daily yoga, is a healthy habit.” And in M.A. Screech’s introduction to his translation of the Essays, he describes it as “one of Europe’s great bedside books.” Alain de Botton likewise included Montaigne in his book The Consolations of Philosophy as a helpful guide for thinking about the problem of self-esteem, and in his book The School of Life, he writes that the Essays “amounted to a practical compendium of advice on helping us to know our fickle minds, find purpose, connect meaningfully with others and achieve intervals of composure and acceptance.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Biggest AI for Biology Yet Writes Genomes From Scratch

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

Mother Nature is perhaps the most powerful generative “intelligence.” With just four genetic letters—A, T, C, and G—she has crafted the dazzling variety of life on Earth.

Mother Nature is perhaps the most powerful generative “intelligence.” With just four genetic letters—A, T, C, and G—she has crafted the dazzling variety of life on Earth.

Can generative AI expand on her work?

A new algorithm, Evo 2, trained on roughly 128,000 genomes—9.3 trillion DNA letter pairs—spanning all of life’s domains, is now the largest generative AI model for biology to date. Built by scientists at the Arc Institute, Stanford University, and Nvidia, Evo 2 can write whole chromosomes and small genomes from scratch. It also learned how DNA mutations affect proteins, RNA, and overall health, shining light on “non-coding” regions, in particular. These mysterious sections of DNA don’t make proteins but often control gene activity and are linked to diseases.

The team has released Evo 2’s software code and model parameters to the scientific community for further exploration. Researchers can also access the tool through a user-friendly web interface. With Evo 2 as a foundation, scientists may develop more specific AI models. These could predict how mutations affect a protein’s function, how genes operate differently across cell types, or even help researchers design new genomes for synthetic biology. Evo marks “a key moment in the emerging field of generative biology” because machines can now read, write, and “think” in the language of DNA, said study author Patrick Hsu in an Arc Institute blog.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

Black Silk

She was cleaning—there is always

that to do—when she found,

at the top of the closet, his old

silk vest. She called me

to look at it, unrolling it carefully

like something live

might fall out. Then we spread it

on the kitchen table and smoothed

the wrinkles down, making our hands

heavy until its shape against Formica

came back and the little tips

that would have pointed to his pockets

lay flat. The buttons were all there.

I held my arms out and she

looped the wide armholes over

them. “That’s one thing I never

wanted to be,” she said, “a man.”

I went into the bathroom to see

how I looked in the sheen and

sadness. Wind chimes

off-key in the alcove. Then her

crying so I stood back in the sink-light

where the porcelain had been staring. Time

to go to here, I thought, with that

other mind, and stood still.

by Tess Gallagher

from Willingly

Graywolf Press 1984

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.