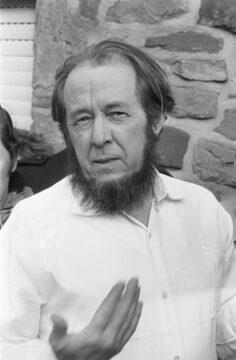

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn at The New Criterion:

How irreversible, how irreparable is this process of mass vulgarization? Judging by the sphere of literature (the sphere closest to me), the path toward a reestablishment of high quality is not yet closed off, not yet taken from us, even if it will require a significant concentration of abilities and efforts. In principle, and according to the very nature of art—according to its flexibility and multifacetedness—the elite and the popular can coexist in a single work of literature: in successful cases, indeed, that work may be multileveled, written in such a way that it is accessible and satisfactory concurrently for readers of diverse levels of understanding and perception; and if a person experiences an elevation of level over time, he reads the same book with a newer understanding. Failure in achieving this is hardly preordained; but the author has to rise above the day-to-day demands of the publishing market, above calculations of assured near-term success.

How irreversible, how irreparable is this process of mass vulgarization? Judging by the sphere of literature (the sphere closest to me), the path toward a reestablishment of high quality is not yet closed off, not yet taken from us, even if it will require a significant concentration of abilities and efforts. In principle, and according to the very nature of art—according to its flexibility and multifacetedness—the elite and the popular can coexist in a single work of literature: in successful cases, indeed, that work may be multileveled, written in such a way that it is accessible and satisfactory concurrently for readers of diverse levels of understanding and perception; and if a person experiences an elevation of level over time, he reads the same book with a newer understanding. Failure in achieving this is hardly preordained; but the author has to rise above the day-to-day demands of the publishing market, above calculations of assured near-term success.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

“If there is one feature that defines the human condition, it is language.” This pronouncement appears on the dust jacket of the new memoir by the linguist Julie Sedivy, Linguaphile: A Life of Language Love, but the idea dates back at least to Aristotle, who asserted that what distinguishes humans from other creatures is “logos,” our ability to think rationally and persuade others through language.

“If there is one feature that defines the human condition, it is language.” This pronouncement appears on the dust jacket of the new memoir by the linguist Julie Sedivy, Linguaphile: A Life of Language Love, but the idea dates back at least to Aristotle, who asserted that what distinguishes humans from other creatures is “logos,” our ability to think rationally and persuade others through language. Several years ago, I left my medical practice for a long vacation. On the morning of my first day back, my alarm went off. I pushed the button in and, for a few minutes, lay with the light off. Then, one at a time, I lowered my feet to the floor. The slow process that would transform me back into an anaesthesiologist had begun.

Several years ago, I left my medical practice for a long vacation. On the morning of my first day back, my alarm went off. I pushed the button in and, for a few minutes, lay with the light off. Then, one at a time, I lowered my feet to the floor. The slow process that would transform me back into an anaesthesiologist had begun. In the nuclear age that followed Oppenheimer’s creation of the atomic bomb, America’s technological monopoly lasted roughly four years before Soviet scientists achieved parity. This balance of terror, combined with the unprecedented destructive potential of these new weapons, gave rise to mutual assured destruction (MAD)—a deterrence framework that, despite its flaws, prevented catastrophic conflict for decades. The stakes of nuclear retaliation discourage each side from striking first, ultimately allowing for a tense but stable standoff.

In the nuclear age that followed Oppenheimer’s creation of the atomic bomb, America’s technological monopoly lasted roughly four years before Soviet scientists achieved parity. This balance of terror, combined with the unprecedented destructive potential of these new weapons, gave rise to mutual assured destruction (MAD)—a deterrence framework that, despite its flaws, prevented catastrophic conflict for decades. The stakes of nuclear retaliation discourage each side from striking first, ultimately allowing for a tense but stable standoff. To enter the Rudolph retrospective at the Met is to be seduced. Enveloped in the museum’s 20th-century art galleries, the clean lines and daring spirit of Rudolph’s drawings place him comfortably in the company of the modern masters nearby. His geometric precision and imaginative forms echo Russian Constructivists like El Lissitzky. Exhibition photographs of Rudolph’s built works alluringly capture the interplay between light and shadow that animate the interiors and exteriors of his massive concrete structures. One featured building is a levitating layer cake improbably balanced on fluted columns; in another mock-up, a concrete snake of triangular apartment buildings slithers its way across Manhattan.

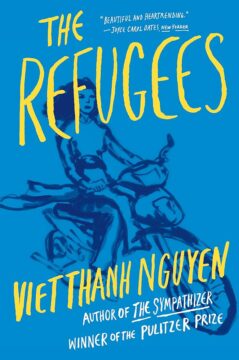

To enter the Rudolph retrospective at the Met is to be seduced. Enveloped in the museum’s 20th-century art galleries, the clean lines and daring spirit of Rudolph’s drawings place him comfortably in the company of the modern masters nearby. His geometric precision and imaginative forms echo Russian Constructivists like El Lissitzky. Exhibition photographs of Rudolph’s built works alluringly capture the interplay between light and shadow that animate the interiors and exteriors of his massive concrete structures. One featured building is a levitating layer cake improbably balanced on fluted columns; in another mock-up, a concrete snake of triangular apartment buildings slithers its way across Manhattan. It is safe to say that perceptions of migrants are contradictory. In their countries of origin, they are sometimes celebrated for having embarked on adventures and sometimes criticized as having abandoned their homes. In the countries of their arrival, they can appear as terrifying threats in another people’s history or be welcomed as fresh blood. If they face hostility and suspicion, migrants might feel the need to insert themselves into their new nation’s chronicles of conquest. The migrant’s heroism can then harmonize with their host nation’s self-image, as well as affirming that nation’s hospitality and generosity.

It is safe to say that perceptions of migrants are contradictory. In their countries of origin, they are sometimes celebrated for having embarked on adventures and sometimes criticized as having abandoned their homes. In the countries of their arrival, they can appear as terrifying threats in another people’s history or be welcomed as fresh blood. If they face hostility and suspicion, migrants might feel the need to insert themselves into their new nation’s chronicles of conquest. The migrant’s heroism can then harmonize with their host nation’s self-image, as well as affirming that nation’s hospitality and generosity. They who in folly or mere greed

They who in folly or mere greed Washington DC. Boston, Massachusetts. Denver, Colorado. Seattle, Washington. Trenton, New Jersey

Washington DC. Boston, Massachusetts. Denver, Colorado. Seattle, Washington. Trenton, New Jersey E

E