Charlie Tyson in the Chronicle of Higher Education:

How easy it would be, a young Susan Sontag considered, to slide into academic life. Make good grades, linger in graduate school, write “a couple of papers on obscure subjects that nobody cares about, and, at the age of sixty, be ugly and respected and a full professor.” Nearly 70 years after this journal entry, the word “ugly,” planted so squarely in the sentence’s final phrase, still stings.

How easy it would be, a young Susan Sontag considered, to slide into academic life. Make good grades, linger in graduate school, write “a couple of papers on obscure subjects that nobody cares about, and, at the age of sixty, be ugly and respected and a full professor.” Nearly 70 years after this journal entry, the word “ugly,” planted so squarely in the sentence’s final phrase, still stings.

Academe styles itself as the aristocracy of the mind; it is generally disdainful of the body and of the luxury goods commercial society finds beautiful. In short, professors distrust beauty. The preening self-abasement with which they do so, Stanley Fish wrote in the 1990s, is why academics take pride in driving Volvos.

In truth, beauty’s conflicted status among academics probably derives less from the elevation of mind over body and more from the long exclusion of women from the professoriate. For most of the 20th century to be a professor was to be male, and therefore theoretically unsexed, and thus seemingly exempt from the female gendered standards of the fashion industry and mass entertainment. Female academics face a double bind: Look attractive and you seem unserious; look homely and you seem dour. Male academics, for their part, loll in ink-stained corduroys and rumpled shirts. The fashion-conscious few adopt intellectual aesthetics, for instance, riffs on Foucault with black turtlenecks, sleek, shaved heads, and big plastic glasses thrown in for good measure.

That academics encounter beauty in their private lives as a mystifying or corrupted alien force was a cliché by the time Fish cast his eye on the faculty parking lot. Yet the inconsistent treatment beauty has received in scholarly research demands explanation. In the humanities, beauty is ignored or seen as a vague embarrassment, and in the social sciences the topic is treated only superficially. If beauty remains a serious subject of study anywhere, it is in the sciences, certain corners of which have enlisted beauty as an organizing ideal.

More here.

The 20th century was a remarkably productive one for physics. First, Albert Einstein’s

The 20th century was a remarkably productive one for physics. First, Albert Einstein’s  Ask people to name the key minds that have shaped America’s burst of radical right-wing attacks on working conditions, consumer rights and public services, and they will typically mention figures like free market-champion Milton Friedman, libertarian guru Ayn Rand, and laissez-faire economists Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises.

Ask people to name the key minds that have shaped America’s burst of radical right-wing attacks on working conditions, consumer rights and public services, and they will typically mention figures like free market-champion Milton Friedman, libertarian guru Ayn Rand, and laissez-faire economists Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises. It is election season in

It is election season in  What’s especially impressive about this adaptation is not only that it is enjoyable, but that it directly confronts the problem of addiction without glamorising it. Other dramas about womanising addicts—for example Mad Men or Californication—tend to focus on the debauchery as much as the interior consequences; this makes it easy for the viewer to avoid processing the trauma. Watching Mad Men’s Don Draper pour himself yet another glass of whiskey, having hit yet another rock bottom, doesn’t quell the desire (provoked by the sexy depiction of the world of the programme) to reach for a cigarette and a whiskey yourself. Even in Channel 4’s Sherlock, the detective’s opium habit is seen as a facet of his genius: a necessary method for him to open the doors of perception. There is something beguiling and (literally) intoxicating about watching someone dance so close to the cliff edge. Indulging this behaviour onscreen can make it seem attractive rather than repellent.

What’s especially impressive about this adaptation is not only that it is enjoyable, but that it directly confronts the problem of addiction without glamorising it. Other dramas about womanising addicts—for example Mad Men or Californication—tend to focus on the debauchery as much as the interior consequences; this makes it easy for the viewer to avoid processing the trauma. Watching Mad Men’s Don Draper pour himself yet another glass of whiskey, having hit yet another rock bottom, doesn’t quell the desire (provoked by the sexy depiction of the world of the programme) to reach for a cigarette and a whiskey yourself. Even in Channel 4’s Sherlock, the detective’s opium habit is seen as a facet of his genius: a necessary method for him to open the doors of perception. There is something beguiling and (literally) intoxicating about watching someone dance so close to the cliff edge. Indulging this behaviour onscreen can make it seem attractive rather than repellent. Around the time that Imasuen was getting yelled at by his mother, the author of “Purple Hibiscus,” Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who is now regarded as one of the most vital and original novelists of her generation, was living in a poky apartment in Baltimore, writing the last sections of her second book. She was twenty-six. “Purple Hibiscus,” published the previous fall, had established her reputation as an up-and-coming writer, but she was not yet well known.

Around the time that Imasuen was getting yelled at by his mother, the author of “Purple Hibiscus,” Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who is now regarded as one of the most vital and original novelists of her generation, was living in a poky apartment in Baltimore, writing the last sections of her second book. She was twenty-six. “Purple Hibiscus,” published the previous fall, had established her reputation as an up-and-coming writer, but she was not yet well known. Heron the critic was also one of the figures responsible for introducing the American abstract expressionists to a British audience. Although he was later to accuse Pollock, De Kooning et al (but not Rothko) of cultural imperialism and not being painterly enough, the scale of their pictures, their rhythm, saturated palette and insistence that each part of the canvas was as important as every other, had a profound effect on him. Heron believed that, “Painting is thinking with one’s hand; or with one’s arm; in fact with one’s whole body,” and the epic AbEx works represented his aphorism in action.

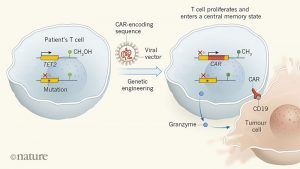

Heron the critic was also one of the figures responsible for introducing the American abstract expressionists to a British audience. Although he was later to accuse Pollock, De Kooning et al (but not Rothko) of cultural imperialism and not being painterly enough, the scale of their pictures, their rhythm, saturated palette and insistence that each part of the canvas was as important as every other, had a profound effect on him. Heron believed that, “Painting is thinking with one’s hand; or with one’s arm; in fact with one’s whole body,” and the epic AbEx works represented his aphorism in action. The use of genetically engineered immune cells to target tumours is one of the most exciting current developments in cancer treatment. In this approach, T cells are taken from a patient and modified in vitro by inserting an engineered version of a gene that encodes a receptor protein. The receptor, known as a chimaeric antigen receptors (CAR), directs the engineered cell, called a CAR T cell, to the patient’s tumour when the cell is transferred back into the body. This therapy can be highly effective for tumours that express the protein CD19, such as B-cell acute leukaemias

The use of genetically engineered immune cells to target tumours is one of the most exciting current developments in cancer treatment. In this approach, T cells are taken from a patient and modified in vitro by inserting an engineered version of a gene that encodes a receptor protein. The receptor, known as a chimaeric antigen receptors (CAR), directs the engineered cell, called a CAR T cell, to the patient’s tumour when the cell is transferred back into the body. This therapy can be highly effective for tumours that express the protein CD19, such as B-cell acute leukaemias

Critics of Goldman Sachs love to say the investment bank highlights the failures of everything from capitalism and neoliberalism to democracy and socialism. Millions of words have been written depicting Goldman as the central villain of the Great Recession, yet little has been said about their most egregious sin: their lobby art. In 2010, Goldman Sachs paid $5 million for a custom-made Julie Meheretu mural for their New York headquarters. Expectations are low for corporate lobby art, yet Meheretu’s giant painting is remarkably ugly—so ugly that it helps us sift through a decade of Goldman criticisms and get to the heart of what is wrong with the elites of our country.

Critics of Goldman Sachs love to say the investment bank highlights the failures of everything from capitalism and neoliberalism to democracy and socialism. Millions of words have been written depicting Goldman as the central villain of the Great Recession, yet little has been said about their most egregious sin: their lobby art. In 2010, Goldman Sachs paid $5 million for a custom-made Julie Meheretu mural for their New York headquarters. Expectations are low for corporate lobby art, yet Meheretu’s giant painting is remarkably ugly—so ugly that it helps us sift through a decade of Goldman criticisms and get to the heart of what is wrong with the elites of our country. In

In  Around 7,000 years ago – all the way back in the Neolithic – something really peculiar happened to human genetic diversity. Over the next 2,000 years, and seen across Africa, Europe and Asia, the genetic diversity of the Y chromosome collapsed, becoming as though there was only one man for every 17 women.

Around 7,000 years ago – all the way back in the Neolithic – something really peculiar happened to human genetic diversity. Over the next 2,000 years, and seen across Africa, Europe and Asia, the genetic diversity of the Y chromosome collapsed, becoming as though there was only one man for every 17 women. Is it possible for two people to simultaneously sexually assault each other? This is the question—rife with legal, anatomical, and emotional improbabilities—to which the University of Cincinnati now addresses itself, and with some urgency, as the institution and three of its employees are currently being sued over an encounter that was sexual for a brief moment, but that just as quickly entered the realm of eternal return. The one important thing you need to know about the case is that according to the lawsuit, a woman has been indefinitely suspended from college because she let a man touch her vagina. What kind of sexually repressive madness could have allowed for this to happen? Answer that question and you will go a long way toward answering the question, “What the hell is happening on American college campuses?”

Is it possible for two people to simultaneously sexually assault each other? This is the question—rife with legal, anatomical, and emotional improbabilities—to which the University of Cincinnati now addresses itself, and with some urgency, as the institution and three of its employees are currently being sued over an encounter that was sexual for a brief moment, but that just as quickly entered the realm of eternal return. The one important thing you need to know about the case is that according to the lawsuit, a woman has been indefinitely suspended from college because she let a man touch her vagina. What kind of sexually repressive madness could have allowed for this to happen? Answer that question and you will go a long way toward answering the question, “What the hell is happening on American college campuses?” I grew up eating

I grew up eating  In an essay

In an essay