Ben Tarnoff in The Guardian:

A boy speaks one language at home and another at school. The white kids want to know where he is from. The answer is “here”, same as them, but that’s not what they’re asking. After 9/11 they call him Osama. His parents are from Pakistan. When he visits Karachi, his relatives point out his US accent. He lives between two worlds, belonging to neither. Then, in the sixth grade, something happens. He is doing a science project on Isaac Newton. He visits the public library of the small town in Pennsylvania where he lives, and, browsing books about Newton the scientist he comes across another Newton – Huey P Newton, cofounder of the Black Panther Party. In 1973, Newton published an autobiography called Revolutionary Suicide. Intrigued by the title, the boy picks up the book, and it changes his life.

A boy speaks one language at home and another at school. The white kids want to know where he is from. The answer is “here”, same as them, but that’s not what they’re asking. After 9/11 they call him Osama. His parents are from Pakistan. When he visits Karachi, his relatives point out his US accent. He lives between two worlds, belonging to neither. Then, in the sixth grade, something happens. He is doing a science project on Isaac Newton. He visits the public library of the small town in Pennsylvania where he lives, and, browsing books about Newton the scientist he comes across another Newton – Huey P Newton, cofounder of the Black Panther Party. In 1973, Newton published an autobiography called Revolutionary Suicide. Intrigued by the title, the boy picks up the book, and it changes his life.

This is the scene that opens Mistaken Identity: Race and Class in the Age of Trump. It’s vividly drawn, and sets the stakes for what follows. Asad Haider has written a book about identity, politics, and the relationship between the two. In particular, he has written a book about “identity politics”, a phrase that, like “political correctness”, is extremely slippery, but which generally means an emphasis on issues of racial, gender and sexual identity. Identity politics finds critics everywhere. Throw a rock at a rack of newspapers and you’ll probably hit an editorial condemning it. Conservatives such as Republican House speaker Paul Ryan blame it for polarisation, while liberals like the Columbia University historian Mark Lilla hold it responsible for Donald Trump’s victory, applying the baroque logic that letting people use their preferred gender pronouns is why Democrats struggle to be seen as the party of working people.

More here.

Many warn that Standard Arabic, or Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), is on the

Many warn that Standard Arabic, or Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), is on the  Would you advise someone to flap towels in a burning house? To bring a flyswatter to a gunfight? Yet the counsel we hear on climate change could scarcely be more out of sync with the nature of the crisis.

Would you advise someone to flap towels in a burning house? To bring a flyswatter to a gunfight? Yet the counsel we hear on climate change could scarcely be more out of sync with the nature of the crisis. What’s in a name? Franklin Delano Roosevelt called himself a Christian, a Democrat, and a liberal. He did not call himself a democratic socialist, or any other kind of socialist. He was, in fact, no socialist at all. Nor was he a conservative or a reactionary, although many on the socialist and communist left charged that he was—including the Communist Party USA, which attacked his New Deal for a time (until Moscow’s political line changed) as American “masked fascization.”

What’s in a name? Franklin Delano Roosevelt called himself a Christian, a Democrat, and a liberal. He did not call himself a democratic socialist, or any other kind of socialist. He was, in fact, no socialist at all. Nor was he a conservative or a reactionary, although many on the socialist and communist left charged that he was—including the Communist Party USA, which attacked his New Deal for a time (until Moscow’s political line changed) as American “masked fascization.” Artificial intelligence (AI) is being embraced by hospitals and other healthcare organizations, which are using the technology to do everything from interpreting CT scans to predicting which patients are most likely to suffer debilitating falls while being treated. Electronic medical records are scoured and run through algorithms designed to help doctors pick the best cancer treatments based on the mutations in patients’ tumors, for example, or to predict their likelihood to respond well to a treatment regimen based on past experiences of similar patients. But do algorithms, robots and machine learning cross ethical boundaries in healthcare? A group of physicians out of Stanford University contend that

Artificial intelligence (AI) is being embraced by hospitals and other healthcare organizations, which are using the technology to do everything from interpreting CT scans to predicting which patients are most likely to suffer debilitating falls while being treated. Electronic medical records are scoured and run through algorithms designed to help doctors pick the best cancer treatments based on the mutations in patients’ tumors, for example, or to predict their likelihood to respond well to a treatment regimen based on past experiences of similar patients. But do algorithms, robots and machine learning cross ethical boundaries in healthcare? A group of physicians out of Stanford University contend that  Artificial Intelligence (AI) is nothing if not controversial. Whether the subject of scrutiny behind hair-raising advances in sex robots which was heavily

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is nothing if not controversial. Whether the subject of scrutiny behind hair-raising advances in sex robots which was heavily D

D BLVR: Yeah, and it made me wonder about your dreams—do you have any recurring dreams?

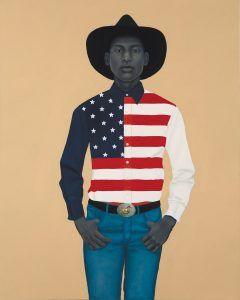

BLVR: Yeah, and it made me wonder about your dreams—do you have any recurring dreams? Grant Wood wanted to make art American. As with so many attempts to make things American, what this meant was distilling a particular region into the essence of the United States. New England and the Deep South are strong contenders, but the Midwest is perhaps the most plausibly all-American region. The visual and cultural tropes of the Midwest are the commonplaces of American kitsch—corn fields, barns, apple pie, churches, Main Street. By choosing to remain in his native Iowa, Wood was well positioned to do what he wanted, without having to forego success. The current Wood retrospective on view at the Whitney (closing June 10th) is hardly the first time his work has received sustained attention from the highest levels of the American art world. The Whitney itself held its last retrospective in 1983, and during Wood’s lifetime he was arguably the most famous artist in the United States. The current show acknowledges that one of Wood’s paintings dominates all other. The exhibition simply uses the name of American Gothic, adding, appropriately, “and other fables” after the obligatory colon.

Grant Wood wanted to make art American. As with so many attempts to make things American, what this meant was distilling a particular region into the essence of the United States. New England and the Deep South are strong contenders, but the Midwest is perhaps the most plausibly all-American region. The visual and cultural tropes of the Midwest are the commonplaces of American kitsch—corn fields, barns, apple pie, churches, Main Street. By choosing to remain in his native Iowa, Wood was well positioned to do what he wanted, without having to forego success. The current Wood retrospective on view at the Whitney (closing June 10th) is hardly the first time his work has received sustained attention from the highest levels of the American art world. The Whitney itself held its last retrospective in 1983, and during Wood’s lifetime he was arguably the most famous artist in the United States. The current show acknowledges that one of Wood’s paintings dominates all other. The exhibition simply uses the name of American Gothic, adding, appropriately, “and other fables” after the obligatory colon. Asad Raza: In 2015, Nicola Lees invited me to do something for the Ljubljana Biennial, and I had a thought of the school, especially experimental pedagogy, as an interesting thing. I asked Jeff and Graham to collaborate on this, as they probably know the subject much, much better than I do. But I was interested in making some formal conditions, let’s say, under which an experimental school could flourish inside an exhibition. I think of these as sketches for an institution that would be up to the 21st century somehow, a multivalent cultural institution that could do exhibitions, that would have education, but the education wouldn’t function in the way that education departments do right now, you know?

Asad Raza: In 2015, Nicola Lees invited me to do something for the Ljubljana Biennial, and I had a thought of the school, especially experimental pedagogy, as an interesting thing. I asked Jeff and Graham to collaborate on this, as they probably know the subject much, much better than I do. But I was interested in making some formal conditions, let’s say, under which an experimental school could flourish inside an exhibition. I think of these as sketches for an institution that would be up to the 21st century somehow, a multivalent cultural institution that could do exhibitions, that would have education, but the education wouldn’t function in the way that education departments do right now, you know? If you bring together two enigmas, do you get a bigger enigma, or do they cancel each other out, like multiplied negative numbers, to produce clarity? The latter, I hope, as I take on Wittgenstein and mysticism.

If you bring together two enigmas, do you get a bigger enigma, or do they cancel each other out, like multiplied negative numbers, to produce clarity? The latter, I hope, as I take on Wittgenstein and mysticism. As misinformation weapons go, fake news is sort of like a cannon: noisy and provocative. Innuendo is like a dirty bomb — invisible, toxic and lingering. I became more aware of the misleading uses of innuendo after I spoke with linguistics professor Andrew Kehler during the run-up to the 2016 election.

As misinformation weapons go, fake news is sort of like a cannon: noisy and provocative. Innuendo is like a dirty bomb — invisible, toxic and lingering. I became more aware of the misleading uses of innuendo after I spoke with linguistics professor Andrew Kehler during the run-up to the 2016 election. After graduation, Thurman settled in Harlem in the 1920s and became a leading (and legendary) figure in the Harlem Renaissance—part of the “niggerati,” as Zora Neale Hurston famously called this influential group of intellectuals and artists. Working with A. Philip Randolph, Thurman became an editor at The Messenger, a political and literary journal, and in 1926 he co-founded, with Hurston, Hughes, Aaron Douglas, Gwendolyn Bennett, and Bruce Nugent, a bold and innovative publication called Fire!!, which featured the work of younger artists but was disliked by the black middle class because of its candid presentation of black life. In 1929, Thurman collaborated with the white playwright William Jourdan Rapp to write and produce Harlem, which ran for 93 performances and became “the first successful play written entirely or in part by a Negro to appear on Broadway.” Thurman believed that African Americans could overcome racial barriers, but he experienced countless incidents of racism during his short life.

After graduation, Thurman settled in Harlem in the 1920s and became a leading (and legendary) figure in the Harlem Renaissance—part of the “niggerati,” as Zora Neale Hurston famously called this influential group of intellectuals and artists. Working with A. Philip Randolph, Thurman became an editor at The Messenger, a political and literary journal, and in 1926 he co-founded, with Hurston, Hughes, Aaron Douglas, Gwendolyn Bennett, and Bruce Nugent, a bold and innovative publication called Fire!!, which featured the work of younger artists but was disliked by the black middle class because of its candid presentation of black life. In 1929, Thurman collaborated with the white playwright William Jourdan Rapp to write and produce Harlem, which ran for 93 performances and became “the first successful play written entirely or in part by a Negro to appear on Broadway.” Thurman believed that African Americans could overcome racial barriers, but he experienced countless incidents of racism during his short life. What would

What would  Refashioning history to include its countless heroines is essential work, long overdue. But what of the future? Will these books, as the introduction to Herstory implores, truly encourage young girls to “take inspiration from these . . . amazing women and girls and shake things up!”? Perhaps. Last year, Science magazine published research investigating the age at which girls begin to think that they are less intellectually brilliant than boys. The study involved reading two stories to children between the ages of five and seven. One, they explained, was about a “really, really smart” person; the other, a “really, really nice” one. Afterwards, the children were asked which was about a girl, and which about a boy. At five, the boys were sure the “really, really smart” character was a boy, the girls equally adamant it was a girl. By six, however, something had changed. In the space of twelve months, the girls had become 20 per cent less likely to think that a clever character could share their gender. According to Dario Cvencek, a research scientist at the University of Washington, the results would be more depressing still had the hero of the book been a mathematician. Children absorb the gender prejudices on display in their environments and reading matter from the age of around five, he says – especially the idea that girls don’t do numbers. The stereotypes portrayed in their reading material become their own stereotypes and, worse still, the limits of their ambitions. The most powerful way to combat this, as the psychologist Nilanjana Dasgupta has found, is through providing successful female role models to small girls before the disease sets in, as a form of “stereotype inoculation”.

Refashioning history to include its countless heroines is essential work, long overdue. But what of the future? Will these books, as the introduction to Herstory implores, truly encourage young girls to “take inspiration from these . . . amazing women and girls and shake things up!”? Perhaps. Last year, Science magazine published research investigating the age at which girls begin to think that they are less intellectually brilliant than boys. The study involved reading two stories to children between the ages of five and seven. One, they explained, was about a “really, really smart” person; the other, a “really, really nice” one. Afterwards, the children were asked which was about a girl, and which about a boy. At five, the boys were sure the “really, really smart” character was a boy, the girls equally adamant it was a girl. By six, however, something had changed. In the space of twelve months, the girls had become 20 per cent less likely to think that a clever character could share their gender. According to Dario Cvencek, a research scientist at the University of Washington, the results would be more depressing still had the hero of the book been a mathematician. Children absorb the gender prejudices on display in their environments and reading matter from the age of around five, he says – especially the idea that girls don’t do numbers. The stereotypes portrayed in their reading material become their own stereotypes and, worse still, the limits of their ambitions. The most powerful way to combat this, as the psychologist Nilanjana Dasgupta has found, is through providing successful female role models to small girls before the disease sets in, as a form of “stereotype inoculation”.

It is not uncommon that I lie about what I do for a living. When meeting strangers, basic introductions quickly turn into conversational quicksand for me. Whether posed for identification, categorization, assessment of social status, or to fill an empty conversation, inquiries about work are difficult to avoid. I know that such questions are innocent attempts to situate me somewhere in the atmosphere; we use the occupational compass to direct us toward an identifiable point in each other’s lives. I know this, and yet the job question, when it comes, often has me squirming for answers. My eyes dart away from the pair in front of me expecting a straightforward reply.

It is not uncommon that I lie about what I do for a living. When meeting strangers, basic introductions quickly turn into conversational quicksand for me. Whether posed for identification, categorization, assessment of social status, or to fill an empty conversation, inquiries about work are difficult to avoid. I know that such questions are innocent attempts to situate me somewhere in the atmosphere; we use the occupational compass to direct us toward an identifiable point in each other’s lives. I know this, and yet the job question, when it comes, often has me squirming for answers. My eyes dart away from the pair in front of me expecting a straightforward reply.