Daniel Kurtz-Phelan in The New York Times:

In 2010, just before Thanksgiving, American foreign-policy makers flew into a panic. The United States government had gotten word that an outfit called WikiLeaks was preparing to release an enormous cache of secret diplomatic cables, in coordination with teams of journalists from this and other newspapers. At the time, I was a policy hand in the State Department. It fell to me and my colleagues to dutifully craft apologies on behalf of our bosses, whose sensitive communications and private insults — speculation about, say, a foreign leader’s mental aptitude or mysterious wealth — were about to become public. They, meanwhile, confronted weightier concerns, scrambling to anticipate the coming fallout. Would missions and sources be compromised? Would activists be exposed to persecution? Would anyone ever talk to American officials again? Almost no one, however, anticipated what would prove to be one of the more lasting consequences of the leak: surprised admiration for American diplomats. “My personal opinion of the State Department has gone up several notches,” the British historian and journalist Timothy Garton Ash wrote. He compared one veteran ambassador’s prose to Evelyn Waugh’s, and deemed other analyses “astute,” “unsentimental” and “hilarious.” Beneath their “dandruffy” exteriors, he concluded after browsing the classified offerings, these diplomats were sharper, and funnier, than they looked.

In 2010, just before Thanksgiving, American foreign-policy makers flew into a panic. The United States government had gotten word that an outfit called WikiLeaks was preparing to release an enormous cache of secret diplomatic cables, in coordination with teams of journalists from this and other newspapers. At the time, I was a policy hand in the State Department. It fell to me and my colleagues to dutifully craft apologies on behalf of our bosses, whose sensitive communications and private insults — speculation about, say, a foreign leader’s mental aptitude or mysterious wealth — were about to become public. They, meanwhile, confronted weightier concerns, scrambling to anticipate the coming fallout. Would missions and sources be compromised? Would activists be exposed to persecution? Would anyone ever talk to American officials again? Almost no one, however, anticipated what would prove to be one of the more lasting consequences of the leak: surprised admiration for American diplomats. “My personal opinion of the State Department has gone up several notches,” the British historian and journalist Timothy Garton Ash wrote. He compared one veteran ambassador’s prose to Evelyn Waugh’s, and deemed other analyses “astute,” “unsentimental” and “hilarious.” Beneath their “dandruffy” exteriors, he concluded after browsing the classified offerings, these diplomats were sharper, and funnier, than they looked.

Ronan Farrow aims to achieve a similar effect in “War on Peace.” At a time when the Trump administration has called for gutting the State Department’s budget and filled foreign-policy jobs with military officers, Farrow draws on both government experience and fresh reporting to offer a lament for the plight of America’s diplomats — and an argument for why it matters. “Classic, old-school diplomacy,” he observes, is “frustrating” and involves “a lot of jet lag.” Yet his wry voice and storytelling take work that is often grueling and dull and make it seem, if not always exciting, at least vividly human. A Foreign Service officer’s hairstyle is “diplomat’s mullet: peace in the front, war in the back”; an Afghan strongman’s choice of décor is “warlord chic,” with “leatherette La-Z-Boy recliners” and “a giant tank full of sharks.”

More here.

TAO LIN’S EIGHTH BOOK, Trip, is his best yet, and it’s all thanks to drugs. Well, perhaps not entirely thanks to drugs. With exercise comes mastery, or at least competence, and Lin has been practicing his idiosyncratic craft for over a decade. His first book was published in 2006, when he was twenty-three; improvement during the intervening years may have been inevitable. But Lin—whose authorial voice, notoriously, is so assiduously literal that it sometimes seems transcribed from a robot failing a Turing test—has never been more creative, precise, or inspired than when he details psychedelics-begotten behavior and theories. The behavior is mostly his own, while the theories are often borrowed from Terence McKenna, the late psilocybin advocate whose YouTube videos started Lin down the path to revitalization. While studying McKenna, Lin began to make radical adjustments to his daily drug routines, which in turn radically affected his mind-set.

TAO LIN’S EIGHTH BOOK, Trip, is his best yet, and it’s all thanks to drugs. Well, perhaps not entirely thanks to drugs. With exercise comes mastery, or at least competence, and Lin has been practicing his idiosyncratic craft for over a decade. His first book was published in 2006, when he was twenty-three; improvement during the intervening years may have been inevitable. But Lin—whose authorial voice, notoriously, is so assiduously literal that it sometimes seems transcribed from a robot failing a Turing test—has never been more creative, precise, or inspired than when he details psychedelics-begotten behavior and theories. The behavior is mostly his own, while the theories are often borrowed from Terence McKenna, the late psilocybin advocate whose YouTube videos started Lin down the path to revitalization. While studying McKenna, Lin began to make radical adjustments to his daily drug routines, which in turn radically affected his mind-set. Humans have long trapped animals in cages, nets and snares, but the tangled webs of vanity, curiosity, cruelty and fear we cast over other creatures may be even more perilous. We see our virtues and vices reflected in animals — hardworking beavers, indolent sloths, innocent lambs, greedy vultures — through a glass darkly. But these well-worn clichés blind us to a world far more dazzling and varied, according to Lucy Cooke, the acclaimed zoology-trained author and documentary filmmaker, in her new book, “The Truth About Animals.” As she writes, “Painting the animal kingdom with our artificial ethical brush denies us the astonishing diversity of life, in all of its blood-drinking, sibling-eating, corpse-shagging glory.” (Yes, corpse shagging. The penguin portion is not for the faint of heart.)

Humans have long trapped animals in cages, nets and snares, but the tangled webs of vanity, curiosity, cruelty and fear we cast over other creatures may be even more perilous. We see our virtues and vices reflected in animals — hardworking beavers, indolent sloths, innocent lambs, greedy vultures — through a glass darkly. But these well-worn clichés blind us to a world far more dazzling and varied, according to Lucy Cooke, the acclaimed zoology-trained author and documentary filmmaker, in her new book, “The Truth About Animals.” As she writes, “Painting the animal kingdom with our artificial ethical brush denies us the astonishing diversity of life, in all of its blood-drinking, sibling-eating, corpse-shagging glory.” (Yes, corpse shagging. The penguin portion is not for the faint of heart.) As well as documenting personal misery, this book is a portrait of a society that has forgotten what it is for. Our economies have become “vast engines for producing nonsense”. Utopian ideals have been abandoned on all sides, replaced by praise for “hardworking families”. The rightwing injunction to “get a job!” is mirrored by the leftwing demand for “more jobs!”

As well as documenting personal misery, this book is a portrait of a society that has forgotten what it is for. Our economies have become “vast engines for producing nonsense”. Utopian ideals have been abandoned on all sides, replaced by praise for “hardworking families”. The rightwing injunction to “get a job!” is mirrored by the leftwing demand for “more jobs!” Ethics today is in a curious state. There is no shortage of people telling us that Western civilization is facing a moral crisis, that the old foundation of Christianity has been removed but nothing has been put in its place. Christian writers such as Alister McGrath and Nick Spencer have warned that we’re running on the moral capital of a religion we’ve long abandoned. It’s only a matter of time before, like Wile E. Coyote, we realize we’ve run off a moral cliff, impossibly suspended in mid-air only as long as we fail to realize there’s nothing under our feet.

Ethics today is in a curious state. There is no shortage of people telling us that Western civilization is facing a moral crisis, that the old foundation of Christianity has been removed but nothing has been put in its place. Christian writers such as Alister McGrath and Nick Spencer have warned that we’re running on the moral capital of a religion we’ve long abandoned. It’s only a matter of time before, like Wile E. Coyote, we realize we’ve run off a moral cliff, impossibly suspended in mid-air only as long as we fail to realize there’s nothing under our feet. It was bound to happen eventually. A group of researchers that may actually be competent and well-funded is investigating

It was bound to happen eventually. A group of researchers that may actually be competent and well-funded is investigating  I was at an academic conference last week, somewhere in America, where we were invited by our hosts to place a ‘preferred pronoun’ sticker on our nametags. “If you could pick one of those up during the next break, we’d appreciate it.” The options were, ‘He’, ‘She’, ‘They’, ‘Ask Me’, and one with a blank space for a write-in. Coming from my adoptive France, I had heard of this new practice in my country of origin, but somehow I had convinced myself that it was mostly mythical. Yet there were the stickers, and there were all my fellow participants, wearing them with straight faces.

I was at an academic conference last week, somewhere in America, where we were invited by our hosts to place a ‘preferred pronoun’ sticker on our nametags. “If you could pick one of those up during the next break, we’d appreciate it.” The options were, ‘He’, ‘She’, ‘They’, ‘Ask Me’, and one with a blank space for a write-in. Coming from my adoptive France, I had heard of this new practice in my country of origin, but somehow I had convinced myself that it was mostly mythical. Yet there were the stickers, and there were all my fellow participants, wearing them with straight faces. As a system, art fairs are like America: They’re broken and no one knows how to fix them. Like America, they also benefit those at the very top more than anyone else, and this gap is only growing. Like America, the art world is preoccupied by spectacle — which means nonstop art fairs, biennials, and other blowouts. Yet the place where new art comes from, where it is seen for free and where almost all the risk and innovation takes place — medium and smaller galleries – are ever pressured by rising art fair costs, shrinking attendance and business at the gallery itself, rents, and overhead. This art-fair industrial complex makes it next to impossible for any medium/small gallery to take a chance on bringing unknown or lower-priced artists to art fairs without risking major financial losses. Meanwhile high-end galleries clean up without showing much, if anything, that’s risky or innovative.

As a system, art fairs are like America: They’re broken and no one knows how to fix them. Like America, they also benefit those at the very top more than anyone else, and this gap is only growing. Like America, the art world is preoccupied by spectacle — which means nonstop art fairs, biennials, and other blowouts. Yet the place where new art comes from, where it is seen for free and where almost all the risk and innovation takes place — medium and smaller galleries – are ever pressured by rising art fair costs, shrinking attendance and business at the gallery itself, rents, and overhead. This art-fair industrial complex makes it next to impossible for any medium/small gallery to take a chance on bringing unknown or lower-priced artists to art fairs without risking major financial losses. Meanwhile high-end galleries clean up without showing much, if anything, that’s risky or innovative. COME SUNDAY, A FILM RELEASED

COME SUNDAY, A FILM RELEASED  Each of the ensuing chapters of 12 Rules is a series of meditations – or, less kindly, digressions – leading up to its titular rule, presented as the solution to a problem revealed therein about life and how to make order out of chaos. The chaos is in turn presented as a universal, ahistorical fact about the nature of Being or human existence. Given all this, it is striking how many of the discussions reduce to advice about how to win at something, anything, nothing in particular: and how not to be a “loser”, in relation to others whose similarity to oneself is secured by the time-honoured narrative device of anthropomorphization, under a more or less thin veneer of scientism. Rule One is “Stand up straight with your shoulders back”, to avoid seeming like a “loser lobster”, who shrinks from conflict and grows sad, sickly and loveless – and is prone to keep on losing, which is portrayed as a disaster.

Each of the ensuing chapters of 12 Rules is a series of meditations – or, less kindly, digressions – leading up to its titular rule, presented as the solution to a problem revealed therein about life and how to make order out of chaos. The chaos is in turn presented as a universal, ahistorical fact about the nature of Being or human existence. Given all this, it is striking how many of the discussions reduce to advice about how to win at something, anything, nothing in particular: and how not to be a “loser”, in relation to others whose similarity to oneself is secured by the time-honoured narrative device of anthropomorphization, under a more or less thin veneer of scientism. Rule One is “Stand up straight with your shoulders back”, to avoid seeming like a “loser lobster”, who shrinks from conflict and grows sad, sickly and loveless – and is prone to keep on losing, which is portrayed as a disaster.

The brutal truth of literary careers is that the reputation of most great writers would not have been affected – and might even have been improved – by earlier death. Philip Roth, though, is a very rare example of a front-rank author whose later work is also the greater work. If the obituaries of Roth had appeared in the mid-Eighties of the last century rather than his own mid-80s this week, then he would likely have been remembered as a writer whose best efforts had been, in two senses, devoted to self-exploration. That early oeuvre might easily have been dismissed as penis-waving – the masturbatory comic classic, Portnoy’s Complaint(1969) – giving way to navel-gazing, in the quartet of stories – from The Ghost Writer (1979) to The Prague Orgy (1985) – that playfully dramatised, via a fictional Jewish American novelist called Nathan Zuckerman, the deranging fame and accusations of anti-semitism that resulted from the novel about the furiously self-abusing young Jew, Alexander Portnoy, or, as he became in Zuckerman’s surrogate version, Carnovsky.

The brutal truth of literary careers is that the reputation of most great writers would not have been affected – and might even have been improved – by earlier death. Philip Roth, though, is a very rare example of a front-rank author whose later work is also the greater work. If the obituaries of Roth had appeared in the mid-Eighties of the last century rather than his own mid-80s this week, then he would likely have been remembered as a writer whose best efforts had been, in two senses, devoted to self-exploration. That early oeuvre might easily have been dismissed as penis-waving – the masturbatory comic classic, Portnoy’s Complaint(1969) – giving way to navel-gazing, in the quartet of stories – from The Ghost Writer (1979) to The Prague Orgy (1985) – that playfully dramatised, via a fictional Jewish American novelist called Nathan Zuckerman, the deranging fame and accusations of anti-semitism that resulted from the novel about the furiously self-abusing young Jew, Alexander Portnoy, or, as he became in Zuckerman’s surrogate version, Carnovsky. Some people heard

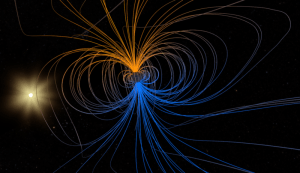

Some people heard  There’s a passage in Carlo Rovelli’s lovely new book, “The Order of Time” — a letter from Einstein to the family of his recently deceased friend Michele Besso: “Now he has departed from this strange world a little ahead of me. That means nothing… The distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.” Rovelli comments that Einstein was taking great poetic license with the temporal findings of his relativity theory, even to the point of error. But then the author goes on to say that the great physicist was addressing his letter not to scientists or philosophers, but to a bereft family. “It’s a letter written to console a grieving sister,” he writes. “A gentle letter, alluding to the spiritual bond between Michele and Albert.” That sensitivity to the human condition is a constant presence in Rovelli’s book — a book that reviews all of the best scientific thinking about the perennial mystery of time, from relativity to quantum physics to the inexorable second law of thermodynamics. Meanwhile, he always returns to us frail human beings — we who struggle to understand not only the external world of atoms and galaxies but also the internal world of our hearts and our minds.

There’s a passage in Carlo Rovelli’s lovely new book, “The Order of Time” — a letter from Einstein to the family of his recently deceased friend Michele Besso: “Now he has departed from this strange world a little ahead of me. That means nothing… The distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.” Rovelli comments that Einstein was taking great poetic license with the temporal findings of his relativity theory, even to the point of error. But then the author goes on to say that the great physicist was addressing his letter not to scientists or philosophers, but to a bereft family. “It’s a letter written to console a grieving sister,” he writes. “A gentle letter, alluding to the spiritual bond between Michele and Albert.” That sensitivity to the human condition is a constant presence in Rovelli’s book — a book that reviews all of the best scientific thinking about the perennial mystery of time, from relativity to quantum physics to the inexorable second law of thermodynamics. Meanwhile, he always returns to us frail human beings — we who struggle to understand not only the external world of atoms and galaxies but also the internal world of our hearts and our minds. In 2015, Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari published Sapiens, a sweeping and widely acclaimed history of humankind. In it, he discusses a phenomenon he calls “humanism.” Humanism, as he defines it, is a family of “religions (that) worship humanity, or more correctly, homo sapiens.” This worship of humanity, he argues, has made modernity “an age of intense religious fervor, unparalleled missionary efforts, and the bloodiest wars of religion in history.” The crimes of genocidal Nazism, Stalinist communism, and environmental destruction, he argues, can all be traced to the central tenets of humanism. If Harari is right, humanists need to engage in some serious soul-searching.

In 2015, Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari published Sapiens, a sweeping and widely acclaimed history of humankind. In it, he discusses a phenomenon he calls “humanism.” Humanism, as he defines it, is a family of “religions (that) worship humanity, or more correctly, homo sapiens.” This worship of humanity, he argues, has made modernity “an age of intense religious fervor, unparalleled missionary efforts, and the bloodiest wars of religion in history.” The crimes of genocidal Nazism, Stalinist communism, and environmental destruction, he argues, can all be traced to the central tenets of humanism. If Harari is right, humanists need to engage in some serious soul-searching. By the time he came to write Finnegans Wake, Joyce had moved beyond trying to imitate musical forms, and described his novel not as a “blending of literature and music”, but rather as “pure music”. Writing to his daughter Lucia, Joyce explained, “Lord knows what my prose means. In a word, it is pleasing to the ear . . . . That is enough, it seems to me”, and in conversation, he declared, “judging from modern trends it seems that all the arts are tending towards the abstraction of music; and what I am writing at present is entirely governed by that purpose”. This offers perhaps the best way to approach his most complex work. Joyce emphasizes how, “if anyone doesn’t understand a passage, all he need do is read it aloud”, and such an approach certainly helps here: “and the rhymers’ world was with reason the richer for a wouldbe ballad, to the balledder of which the world of cumannity singing owes a tribute for having placed on the planet’s melomap his lay of the vilest bogeyer but most attractionable avatar the world has ever had to explain for”.

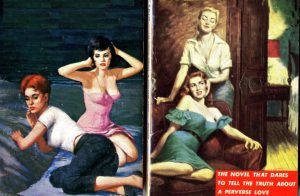

By the time he came to write Finnegans Wake, Joyce had moved beyond trying to imitate musical forms, and described his novel not as a “blending of literature and music”, but rather as “pure music”. Writing to his daughter Lucia, Joyce explained, “Lord knows what my prose means. In a word, it is pleasing to the ear . . . . That is enough, it seems to me”, and in conversation, he declared, “judging from modern trends it seems that all the arts are tending towards the abstraction of music; and what I am writing at present is entirely governed by that purpose”. This offers perhaps the best way to approach his most complex work. Joyce emphasizes how, “if anyone doesn’t understand a passage, all he need do is read it aloud”, and such an approach certainly helps here: “and the rhymers’ world was with reason the richer for a wouldbe ballad, to the balledder of which the world of cumannity singing owes a tribute for having placed on the planet’s melomap his lay of the vilest bogeyer but most attractionable avatar the world has ever had to explain for”. Another early lesbian-pulp and layered reading experience is Spring Fire (1952), by Vin Packer (one of the pseudonyms of the prolific author Marijane Meaker). Although its seemingly naive Americana tone reads today as camp, the novel plays with semantics and morality in its own way. Within this supposed “steamy page-turner … once told in whispers” is the tale of a newbie Midwestern student named Susan Mitchell. (She goes by—you guessed it—Mitch.) Mitch is seduced by her sorority sister, the come-hither green-eyed Leda, when she asks Mitch to give her a back rub and then suddenly “rolled over and lay with her breasts pushed up toward Mitch’s hands.” Although the prose at first rings as high-strung, it echoes with complex undertones. “There are a lot of people who love both [men and women] and no one gives a damn, and they just say you’re oversexed,” Leda explains to Mitch. “But they start getting interested when you stick to one sex. Like you’ve been doing, Mitch. I couldn’t love you if you were a Lesbian.” (Note the capital l.)

Another early lesbian-pulp and layered reading experience is Spring Fire (1952), by Vin Packer (one of the pseudonyms of the prolific author Marijane Meaker). Although its seemingly naive Americana tone reads today as camp, the novel plays with semantics and morality in its own way. Within this supposed “steamy page-turner … once told in whispers” is the tale of a newbie Midwestern student named Susan Mitchell. (She goes by—you guessed it—Mitch.) Mitch is seduced by her sorority sister, the come-hither green-eyed Leda, when she asks Mitch to give her a back rub and then suddenly “rolled over and lay with her breasts pushed up toward Mitch’s hands.” Although the prose at first rings as high-strung, it echoes with complex undertones. “There are a lot of people who love both [men and women] and no one gives a damn, and they just say you’re oversexed,” Leda explains to Mitch. “But they start getting interested when you stick to one sex. Like you’ve been doing, Mitch. I couldn’t love you if you were a Lesbian.” (Note the capital l.)