Tom Bissell in The New York Times:

Well, why does anyone take drugs? The simplest answer is that drugs are generally fun to take, until they aren’t. But psychedelics are different. They don’t drape you in marijuana’s gauzy haze or imbue you with cocaine’s wintry, italicized focus. They’re nothing like opioids, which balance the human body on a knife’s edge between pleasure and death. Psychedelics are to drugs what the Pyramids are to architecture — majestic, ancient and a little frightening. Pollan persuasively argues that our anxieties are misplaced when it comes to psychedelics, most of which are nonaddictive. They also fail to produce what Pollan calls the “physiological noise” of other psychoactive drugs. All things considered, LSD is probably less harmful to the human body than Diet Dr Pepper.

Well, why does anyone take drugs? The simplest answer is that drugs are generally fun to take, until they aren’t. But psychedelics are different. They don’t drape you in marijuana’s gauzy haze or imbue you with cocaine’s wintry, italicized focus. They’re nothing like opioids, which balance the human body on a knife’s edge between pleasure and death. Psychedelics are to drugs what the Pyramids are to architecture — majestic, ancient and a little frightening. Pollan persuasively argues that our anxieties are misplaced when it comes to psychedelics, most of which are nonaddictive. They also fail to produce what Pollan calls the “physiological noise” of other psychoactive drugs. All things considered, LSD is probably less harmful to the human body than Diet Dr Pepper.

Disclaimer aside, nothing in Pollan’s book argues for the recreational use or abuse of psychedelic drugs. What it does argue is that psychedelic-aided therapy, properly conducted by trained professionals — what Pollan calls White-Coat Shamanism — can be personally transformative, helping with everything from overcoming addiction to easing the existential terror of the terminally ill. The strange thing is we’ve been here with psychedelics before.

LSD was first synthesized (from a grain fungus) in 1938, by a chemist working for the Swiss pharmaceutical firm Sandoz. A few years later, not having any idea what he’d created, the chemist accidentally dosed himself and went on to have a notably interesting afternoon. With LSD, Sandoz knew it had something on its hands, but wasn’t sure what. Its management decided to send out free samples to researchers on request, which went on for more than a decade. By the 1950s, scientists studying LSD had discovered serotonin, figured out that the human brain was full of something called neurotransmitters and begun inching toward the development of the first antidepressants. LSD showed such promise in treating alcoholism that the A.A. founder Bill Wilson considered including LSD treatment in his program. So-called magic mushrooms — and the mind-altering psilocybin they contain — arrived a bit later to the scene, having been reintroduced to the Western world thanks to a 1957 Life magazine article, but they proved just as rich in therapeutic possibilities.

More here.

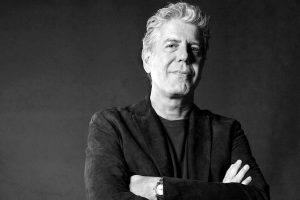

Anthony Bourdain, whose madcap memoir about the dark corners of New York’s restaurants made him into a celebrity chef and touched off a nearly two-decade career as a globe-trotting television host, was found dead in his hotel room in France on Friday. He was 61.

Anthony Bourdain, whose madcap memoir about the dark corners of New York’s restaurants made him into a celebrity chef and touched off a nearly two-decade career as a globe-trotting television host, was found dead in his hotel room in France on Friday. He was 61. Good food, good eating, is all about blood and organs, cruelty and decay. It’s about sodium-loaded pork fat, stinky triple-cream cheeses, the tender thymus glands and distended livers of young animals. It’s about danger—risking the dark, bacterial forces of beef, chicken, cheese, and shellfish. Your first two hundred and seven Wellfleet oysters may transport you to a state of rapture, but your two hundred and eighth may send you to bed with the sweats, chills, and vomits.

Good food, good eating, is all about blood and organs, cruelty and decay. It’s about sodium-loaded pork fat, stinky triple-cream cheeses, the tender thymus glands and distended livers of young animals. It’s about danger—risking the dark, bacterial forces of beef, chicken, cheese, and shellfish. Your first two hundred and seven Wellfleet oysters may transport you to a state of rapture, but your two hundred and eighth may send you to bed with the sweats, chills, and vomits. They are highly virtuosic pieces, which, I assume, must not be played slowly, because then you would hear and see nothing, just as when you walk too slowly past a fence, you perceive the flashes of life from behind it not as a cohesive picture, but rather only as disparate snapshots. The first etude, “In C,” is indeed, as the title reveals, built around this fundamental note. It conveys a mysteriously contemplative and at the same time very harmonious impression. In several slow breaths, flickering structures are built up repeatedly to towering heights. In the second part, nested rhythms become so dense that they generate the gingerbread men feeling. The etude is heading for a climax, but then no explosive outburst occurs; instead, individual melodic lines break free in a high register and simply waft away.

They are highly virtuosic pieces, which, I assume, must not be played slowly, because then you would hear and see nothing, just as when you walk too slowly past a fence, you perceive the flashes of life from behind it not as a cohesive picture, but rather only as disparate snapshots. The first etude, “In C,” is indeed, as the title reveals, built around this fundamental note. It conveys a mysteriously contemplative and at the same time very harmonious impression. In several slow breaths, flickering structures are built up repeatedly to towering heights. In the second part, nested rhythms become so dense that they generate the gingerbread men feeling. The etude is heading for a climax, but then no explosive outburst occurs; instead, individual melodic lines break free in a high register and simply waft away. For much of the 1980s, André Gregory rehearsed Chekhov nearby in another boarded up Broadway jewel, the ruined Victory

For much of the 1980s, André Gregory rehearsed Chekhov nearby in another boarded up Broadway jewel, the ruined Victory

But Podemos

But Podemos The use of local produce is something you might think it more likely to find advertised in a gallery’s café, than at the opening of the exhibition itself. At the Yorkshire Sculpture Park’s retrospective of the works of the Italian sculptor Giuseppe Penone, however, a credit tells you that the potatoes for one of the exhibts were supplied by W. Moore and Son and Bradshaw Wholesale Ltd.

The use of local produce is something you might think it more likely to find advertised in a gallery’s café, than at the opening of the exhibition itself. At the Yorkshire Sculpture Park’s retrospective of the works of the Italian sculptor Giuseppe Penone, however, a credit tells you that the potatoes for one of the exhibts were supplied by W. Moore and Son and Bradshaw Wholesale Ltd. Every two years, a few dozen nations deputize a small circle of curators and thinkers to represent them at the show; many of the participating countries are regulars, with permanent pavilions of their own, often dating back to the early 20th century, and located in the leafy Giardini della Biennale near Venice’s easternmost tip. But each edition of the exhibition also brings a batch of wildcards, never-before-seen entrants whose homelands have decided, for whatever reason, to throw their hats into the ring. This year, first-timers included Guatemala, Saudi Arabia, and Lebanon. And social media (full disclosure: mine included) took a special shine to the premier outing from the Vatican, a brace of inventive freestanding chapels by architects both well- and lesser-known. There was one rookie nation, however, whose appearance at the Biennale was especially poignant, both for the character of its installation and for the mere fact of its being in Venice at all: Pakistan.

Every two years, a few dozen nations deputize a small circle of curators and thinkers to represent them at the show; many of the participating countries are regulars, with permanent pavilions of their own, often dating back to the early 20th century, and located in the leafy Giardini della Biennale near Venice’s easternmost tip. But each edition of the exhibition also brings a batch of wildcards, never-before-seen entrants whose homelands have decided, for whatever reason, to throw their hats into the ring. This year, first-timers included Guatemala, Saudi Arabia, and Lebanon. And social media (full disclosure: mine included) took a special shine to the premier outing from the Vatican, a brace of inventive freestanding chapels by architects both well- and lesser-known. There was one rookie nation, however, whose appearance at the Biennale was especially poignant, both for the character of its installation and for the mere fact of its being in Venice at all: Pakistan. Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fire, which reworks Sophocles’ tragedy Antigone to tell the story of a British Muslim family’s connection to Islamic State, has won the Women’s prize for fiction, acclaimed by judges as “the story of our times”.

Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fire, which reworks Sophocles’ tragedy Antigone to tell the story of a British Muslim family’s connection to Islamic State, has won the Women’s prize for fiction, acclaimed by judges as “the story of our times”. I’ve been a psychology professor since 2012. In the past six years, I’ve witnessed students of all ages procrastinate on papers, skip presentation days, miss assignments, and let due dates fly by. I’ve seen promising prospective grad students fail to get applications in on time; I’ve watched PhD candidates take months or years revising a single dissertation draft; I once had a student who enrolled in the same class of mine two semesters in a row, and never turned in anything either time.

I’ve been a psychology professor since 2012. In the past six years, I’ve witnessed students of all ages procrastinate on papers, skip presentation days, miss assignments, and let due dates fly by. I’ve seen promising prospective grad students fail to get applications in on time; I’ve watched PhD candidates take months or years revising a single dissertation draft; I once had a student who enrolled in the same class of mine two semesters in a row, and never turned in anything either time. The cost of college is a notoriously complex subject. The list price at many private colleges, including tuition, fees, room and board, has reached the bewildering sum of $70,000 a year. But the real price, taking into account financial aid, is often vastly lower.

The cost of college is a notoriously complex subject. The list price at many private colleges, including tuition, fees, room and board, has reached the bewildering sum of $70,000 a year. But the real price, taking into account financial aid, is often vastly lower. A

A  What is Essayism? Its writer admits to us that he has ‘no clue how to write about the essay as a stable entity or established class, how to trace its history diligently from uncertain origins through successive phases of literary dominance’ – and praise be for that. The book is instead a series of attempts, of essays, of course, at delineating or describing the form. Each chapter is a few pages, beginning with an idea: ‘On essays and essayists’, ‘On origins’, ‘On lists’, and as the book begins to become something else, ‘On consolation’. The book is also a story of the book being written, and of Dillon going under entirely. ‘Each day I sat at my desk in an office at the end of the garden,’ he tells us, early on, ‘and cried and smoked and tried to write – tried to write this book – and each day finally gave myself up to fantasies of suicide. I would walk out of this suburb along country lanes to a secluded stretch of railway line and lay my head on the track in the moonlight.’

What is Essayism? Its writer admits to us that he has ‘no clue how to write about the essay as a stable entity or established class, how to trace its history diligently from uncertain origins through successive phases of literary dominance’ – and praise be for that. The book is instead a series of attempts, of essays, of course, at delineating or describing the form. Each chapter is a few pages, beginning with an idea: ‘On essays and essayists’, ‘On origins’, ‘On lists’, and as the book begins to become something else, ‘On consolation’. The book is also a story of the book being written, and of Dillon going under entirely. ‘Each day I sat at my desk in an office at the end of the garden,’ he tells us, early on, ‘and cried and smoked and tried to write – tried to write this book – and each day finally gave myself up to fantasies of suicide. I would walk out of this suburb along country lanes to a secluded stretch of railway line and lay my head on the track in the moonlight.’ The questioning of long-held beliefs and understanding of the full histories behind institutions should have positive repercussions for everyone. But as the Brooklyn, Liverpool and Birmingham cases highlight, decolonizing cultural institutions is not straightforward. Their attempts suggest that the key issue at this early stage is a lack of understanding about what decolonizing an institution means, and what it entails. A genuinely decolonial approach would see museums interrogate their positions as apparently objective caretakers of non-Western objects and artefacts. The assumption of Western objectivity is not only divorced from the material conditions in which those objects have come to be “owned” by Western knowledge – knowledge informed by a history of contact on unequal terms – but it also instantiates the exceptionalism with which Western cultures have felt entitled to the final, objective say on other cultures. By acknowledging this, and then pursuing new roles and missions, institutions could take a number of concrete steps, such as repatriating objects where feasible, especially if they were plundered from peoples for whom they sustain cultural value; embracing greater accountability towards their local communities; and consider the colonial and racial legacies informing their operations and governance.

The questioning of long-held beliefs and understanding of the full histories behind institutions should have positive repercussions for everyone. But as the Brooklyn, Liverpool and Birmingham cases highlight, decolonizing cultural institutions is not straightforward. Their attempts suggest that the key issue at this early stage is a lack of understanding about what decolonizing an institution means, and what it entails. A genuinely decolonial approach would see museums interrogate their positions as apparently objective caretakers of non-Western objects and artefacts. The assumption of Western objectivity is not only divorced from the material conditions in which those objects have come to be “owned” by Western knowledge – knowledge informed by a history of contact on unequal terms – but it also instantiates the exceptionalism with which Western cultures have felt entitled to the final, objective say on other cultures. By acknowledging this, and then pursuing new roles and missions, institutions could take a number of concrete steps, such as repatriating objects where feasible, especially if they were plundered from peoples for whom they sustain cultural value; embracing greater accountability towards their local communities; and consider the colonial and racial legacies informing their operations and governance. In 1826, at the age of 20, John Stuart Mill sank into a suicidal depression, which was bitterly ironic, because his entire upbringing was governed by the maximisation of happiness. How this philosopher clambered out of the despair generated by an arch-rational philosophy can teach us an important lesson about suffering. Inspired by Jeremy Bentham’s ideals, James Mill’s rigorous tutelage of his son involved useful subjects subordinated to the utilitarian goal of bringing about the greatest good for the greatest number. Music played a small part in the curriculum, as it was sufficiently mathematical – an early ‘Mozart for brain development’. Otherwise, subjects useless to material improvement were excluded. When J S Mill applied to Cambridge at the age of 15, he’d so mastered law, history, philosophy, economics, science and mathematics that they turned him away because their professors didn’t have anything more to teach him.

In 1826, at the age of 20, John Stuart Mill sank into a suicidal depression, which was bitterly ironic, because his entire upbringing was governed by the maximisation of happiness. How this philosopher clambered out of the despair generated by an arch-rational philosophy can teach us an important lesson about suffering. Inspired by Jeremy Bentham’s ideals, James Mill’s rigorous tutelage of his son involved useful subjects subordinated to the utilitarian goal of bringing about the greatest good for the greatest number. Music played a small part in the curriculum, as it was sufficiently mathematical – an early ‘Mozart for brain development’. Otherwise, subjects useless to material improvement were excluded. When J S Mill applied to Cambridge at the age of 15, he’d so mastered law, history, philosophy, economics, science and mathematics that they turned him away because their professors didn’t have anything more to teach him.