Marcela Maus in Nature:

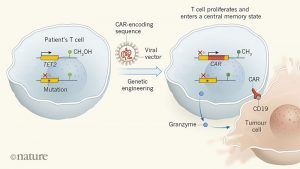

The use of genetically engineered immune cells to target tumours is one of the most exciting current developments in cancer treatment. In this approach, T cells are taken from a patient and modified in vitro by inserting an engineered version of a gene that encodes a receptor protein. The receptor, known as a chimaeric antigen receptors (CAR), directs the engineered cell, called a CAR T cell, to the patient’s tumour when the cell is transferred back into the body. This therapy can be highly effective for tumours that express the protein CD19, such as B-cell acute leukaemias1,2 and large-cell lymphomas3,4. However, some people do not respond to CAR T cells, and efforts to optimize this therapy are ongoing. In a paper in Nature, Fraietta et al.5 report the fortuitous identification of a gene that positively affected one person’s response to treatment with CAR T cells.

The use of genetically engineered immune cells to target tumours is one of the most exciting current developments in cancer treatment. In this approach, T cells are taken from a patient and modified in vitro by inserting an engineered version of a gene that encodes a receptor protein. The receptor, known as a chimaeric antigen receptors (CAR), directs the engineered cell, called a CAR T cell, to the patient’s tumour when the cell is transferred back into the body. This therapy can be highly effective for tumours that express the protein CD19, such as B-cell acute leukaemias1,2 and large-cell lymphomas3,4. However, some people do not respond to CAR T cells, and efforts to optimize this therapy are ongoing. In a paper in Nature, Fraietta et al.5 report the fortuitous identification of a gene that positively affected one person’s response to treatment with CAR T cells.

Therapies involving engineered immune cells use viral vectors based on retroviruses or lentiviruses to insert a DNA sequence, such as one encoding a CAR, into a person’s T cells. However, given that there is no control over where the sequence inserts into the genome, it is possible that the engineered gene could insert at a location that disrupts another, important gene. In the early 2000s, a clinical trial6 enrolled people with immunodeficiencies arising from the lack of a functional copy of a particular immune gene. The trial used viral vectors to insert a wild-type copy of this gene into their stem cells. Unfortunately, however, several people developed uncontrolled T-cell proliferation that evolved into T-cell leukaemia. This event was linked7 to the gene inserting within the sequence of the LMO2gene, disrupting the normal regulation of LMO2.

The pattern of genomic integration sites for various viral vectors has been found to be specific for a given combination of vector and cell type8. In a study of people who had T cells modified using retroviral vectors, the integration events were not implicated as the cause of any cancers9. Lentiviral vectors integrate randomly into the genome but tend to preferentially locate at sites of transcriptionally active genes10. Although random integration is generally thought to be safe, any disruption of the genome nevertheless confers a risk of unwanted consequences.

More here.

Critics of Goldman Sachs love to say the investment bank highlights the failures of everything from capitalism and neoliberalism to democracy and socialism. Millions of words have been written depicting Goldman as the central villain of the Great Recession, yet little has been said about their most egregious sin: their lobby art. In 2010, Goldman Sachs paid $5 million for a custom-made Julie Meheretu mural for their New York headquarters. Expectations are low for corporate lobby art, yet Meheretu’s giant painting is remarkably ugly—so ugly that it helps us sift through a decade of Goldman criticisms and get to the heart of what is wrong with the elites of our country.

Critics of Goldman Sachs love to say the investment bank highlights the failures of everything from capitalism and neoliberalism to democracy and socialism. Millions of words have been written depicting Goldman as the central villain of the Great Recession, yet little has been said about their most egregious sin: their lobby art. In 2010, Goldman Sachs paid $5 million for a custom-made Julie Meheretu mural for their New York headquarters. Expectations are low for corporate lobby art, yet Meheretu’s giant painting is remarkably ugly—so ugly that it helps us sift through a decade of Goldman criticisms and get to the heart of what is wrong with the elites of our country. In

In  Around 7,000 years ago – all the way back in the Neolithic – something really peculiar happened to human genetic diversity. Over the next 2,000 years, and seen across Africa, Europe and Asia, the genetic diversity of the Y chromosome collapsed, becoming as though there was only one man for every 17 women.

Around 7,000 years ago – all the way back in the Neolithic – something really peculiar happened to human genetic diversity. Over the next 2,000 years, and seen across Africa, Europe and Asia, the genetic diversity of the Y chromosome collapsed, becoming as though there was only one man for every 17 women. Is it possible for two people to simultaneously sexually assault each other? This is the question—rife with legal, anatomical, and emotional improbabilities—to which the University of Cincinnati now addresses itself, and with some urgency, as the institution and three of its employees are currently being sued over an encounter that was sexual for a brief moment, but that just as quickly entered the realm of eternal return. The one important thing you need to know about the case is that according to the lawsuit, a woman has been indefinitely suspended from college because she let a man touch her vagina. What kind of sexually repressive madness could have allowed for this to happen? Answer that question and you will go a long way toward answering the question, “What the hell is happening on American college campuses?”

Is it possible for two people to simultaneously sexually assault each other? This is the question—rife with legal, anatomical, and emotional improbabilities—to which the University of Cincinnati now addresses itself, and with some urgency, as the institution and three of its employees are currently being sued over an encounter that was sexual for a brief moment, but that just as quickly entered the realm of eternal return. The one important thing you need to know about the case is that according to the lawsuit, a woman has been indefinitely suspended from college because she let a man touch her vagina. What kind of sexually repressive madness could have allowed for this to happen? Answer that question and you will go a long way toward answering the question, “What the hell is happening on American college campuses?” I grew up eating

I grew up eating  In an essay

In an essay Jim Holt has a new book out, a collection of essays entitled

Jim Holt has a new book out, a collection of essays entitled

The photographer Arthur Fellig, better known as Weegee, lugged his enormous Speed Graphic camera around the nighttime streets of New York City in the 1930s and ’40s, cultivating a persona as stark and as memorable as his tabloid pictures. He was the wisecracking tummler in the rumpled suit, always on the lookout for a car crash or a dead gangster.

The photographer Arthur Fellig, better known as Weegee, lugged his enormous Speed Graphic camera around the nighttime streets of New York City in the 1930s and ’40s, cultivating a persona as stark and as memorable as his tabloid pictures. He was the wisecracking tummler in the rumpled suit, always on the lookout for a car crash or a dead gangster. A

A Country fans no longer resemble the characters in country songs; they are salaried accountants chewing Nicorette in Chevy Tahoes, not railroad linemen spitting Copenhagen through the shot-out windows of a Ford F-150. Their assimilation worries them, and they sometimes overcompensate. “If any of you tuned in to ABC tonight expecting to see the new show Black-ish,” said host Brad Paisley at the 2014 Country Music Association Awards, referring to the sitcom about assimilation anxiety in the suburbs, “this ain’t it. In the meantime, I hope y’all are enjoying white-ish.” The joke had another meaning, too, which Paisley probably didn’t intend: Despite the perception that country is white America’s music, it’s only ever been white-ish. “Country” descended from British and Celtic ballads that crossed the ocean into Appalachia and the South, where singers Americanized the names of the women and the rivers. It was stirred with Baptist hymns, black American folk songs, New Orleans jazz, and—crucially—the twelve-bar blues. Was the sound white? Was it native? The banjo derived from the African gourd-based banjar.

Country fans no longer resemble the characters in country songs; they are salaried accountants chewing Nicorette in Chevy Tahoes, not railroad linemen spitting Copenhagen through the shot-out windows of a Ford F-150. Their assimilation worries them, and they sometimes overcompensate. “If any of you tuned in to ABC tonight expecting to see the new show Black-ish,” said host Brad Paisley at the 2014 Country Music Association Awards, referring to the sitcom about assimilation anxiety in the suburbs, “this ain’t it. In the meantime, I hope y’all are enjoying white-ish.” The joke had another meaning, too, which Paisley probably didn’t intend: Despite the perception that country is white America’s music, it’s only ever been white-ish. “Country” descended from British and Celtic ballads that crossed the ocean into Appalachia and the South, where singers Americanized the names of the women and the rivers. It was stirred with Baptist hymns, black American folk songs, New Orleans jazz, and—crucially—the twelve-bar blues. Was the sound white? Was it native? The banjo derived from the African gourd-based banjar. Few have inspired the Movement for Black Lives as much as James Baldwin. His books that plumb the psychological depths of U.S. racism, notably Notes of a Native Son (1955) and The Fire Next Time (1963), speak to the present in ways that seem not only relevant but prophetic. However, Baldwin’s renewed status as a household name, cemented by the critical success of Raoul Peck’s 2016 film I Am Not Your Negro, makes it easy to forget that for several decades Baldwin fell from public favor.

Few have inspired the Movement for Black Lives as much as James Baldwin. His books that plumb the psychological depths of U.S. racism, notably Notes of a Native Son (1955) and The Fire Next Time (1963), speak to the present in ways that seem not only relevant but prophetic. However, Baldwin’s renewed status as a household name, cemented by the critical success of Raoul Peck’s 2016 film I Am Not Your Negro, makes it easy to forget that for several decades Baldwin fell from public favor. A boy speaks one language at home and another at school. The white kids want to know where he is from. The answer is “here”, same as them, but that’s not what they’re asking. After

A boy speaks one language at home and another at school. The white kids want to know where he is from. The answer is “here”, same as them, but that’s not what they’re asking. After