John Carreyrou in Wired:

ALAN BEAM WAS sitting in his office reviewing lab reports when Theranos CEO and founder Elizabeth Holmes poked her head in and asked him to follow her. She wanted to show him something. They stepped outside the lab into an area of open office space where other employees had gathered. At her signal, a technician pricked a volunteer’s finger, then applied a transparent plastic implement shaped like a miniature rocket to the blood oozing from it. This was the Theranos sample collection device. Its tip collected the blood and transferred it to two little engines at the rocket’s base. The engines weren’t really engines: They were nanotainers. To complete the transfer, you pushed the nanotainers into the belly of the plastic rocket like a plunger. The movement created a vacuum that sucked the blood into them. Or at least that was the idea. But in this instance, things didn’t go quite as planned. When the technician pushed the tiny twin tubes into the device, there was a loud pop and blood splattered everywhere. One of the nanotainers had just exploded. Holmes looked unfazed. “OK, let’s try that again,” she said calmly. Beam1 wasn’t sure what to make of the scene. He’d only been working at Theranos, the Silicon Valley company that promised to offer fast, cheap blood tests from a single drop of blood, for a few weeks and was still trying to get his bearings.

ALAN BEAM WAS sitting in his office reviewing lab reports when Theranos CEO and founder Elizabeth Holmes poked her head in and asked him to follow her. She wanted to show him something. They stepped outside the lab into an area of open office space where other employees had gathered. At her signal, a technician pricked a volunteer’s finger, then applied a transparent plastic implement shaped like a miniature rocket to the blood oozing from it. This was the Theranos sample collection device. Its tip collected the blood and transferred it to two little engines at the rocket’s base. The engines weren’t really engines: They were nanotainers. To complete the transfer, you pushed the nanotainers into the belly of the plastic rocket like a plunger. The movement created a vacuum that sucked the blood into them. Or at least that was the idea. But in this instance, things didn’t go quite as planned. When the technician pushed the tiny twin tubes into the device, there was a loud pop and blood splattered everywhere. One of the nanotainers had just exploded. Holmes looked unfazed. “OK, let’s try that again,” she said calmly. Beam1 wasn’t sure what to make of the scene. He’d only been working at Theranos, the Silicon Valley company that promised to offer fast, cheap blood tests from a single drop of blood, for a few weeks and was still trying to get his bearings.

He knew the nanotainer was part of the company’s proprietary blood-testing system, but he’d never seen one in action before. He hoped this was just a small mishap that didn’t portend bigger problems. The lanky pathologist’s circuitous route to Silicon Valley had started in South Africa, where he grew up. After majoring in English at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg (“Wits” to South Africans), he’d moved to the United States to take premed classes at Columbia University in New York City. The choice was guided by his conservative Jewish parents, who considered only a few professions acceptable for their son: law, business, and medicine.

More here.

Identity politics has engulfed the humanities and social sciences on American campuses; now it is taking over the hard sciences. The STEM fields—science, technology, engineering, and math—are under attack for being insufficiently “diverse.” The pressure to increase the representation of females, blacks, and Hispanics comes from the federal government, university administrators, and scientific societies themselves. That pressure is changing how science is taught and how scientific qualifications are evaluated. The results will be disastrous for scientific innovation and for American competitiveness.

Identity politics has engulfed the humanities and social sciences on American campuses; now it is taking over the hard sciences. The STEM fields—science, technology, engineering, and math—are under attack for being insufficiently “diverse.” The pressure to increase the representation of females, blacks, and Hispanics comes from the federal government, university administrators, and scientific societies themselves. That pressure is changing how science is taught and how scientific qualifications are evaluated. The results will be disastrous for scientific innovation and for American competitiveness.  It’s a tough time to defend religion. Respect for it has diminished in almost every corner of modern life — not just among atheists and intellectuals, but among the wider public, too. And

It’s a tough time to defend religion. Respect for it has diminished in almost every corner of modern life — not just among atheists and intellectuals, but among the wider public, too. And  The oldest stone tools outside Africa have been discovered in western China, scientists reported on Wednesday. Made by ancient members of the human lineage, called hominins, the chipped rocks

The oldest stone tools outside Africa have been discovered in western China, scientists reported on Wednesday. Made by ancient members of the human lineage, called hominins, the chipped rocks  For nearly 40 years, the gender gap in voting has been the subject of continued speculation. How much does it matter? Would it be wide enough to put Democrats in office? Now, with President Trump ascendant, the question becomes still more urgent: What happens if the gender gap becomes a gender chasm?

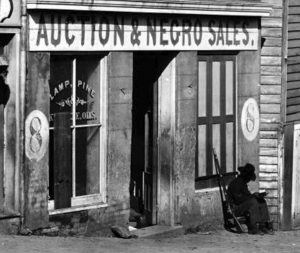

For nearly 40 years, the gender gap in voting has been the subject of continued speculation. How much does it matter? Would it be wide enough to put Democrats in office? Now, with President Trump ascendant, the question becomes still more urgent: What happens if the gender gap becomes a gender chasm? Tribalism and slavery are as old as humanity. The very first human records are records of human bondage. Reports estimate that today 60 million people are held as slaves. While each one of these lives represents an unacceptable tragedy, not one occurs with the approval of law. And that is revolutionary. For while slavery is as old as humanity, abolitionism is a relatively recent phenomenon that did not emerge until the ideas and ideals of the Enlightenment nurtured it into existence.

Tribalism and slavery are as old as humanity. The very first human records are records of human bondage. Reports estimate that today 60 million people are held as slaves. While each one of these lives represents an unacceptable tragedy, not one occurs with the approval of law. And that is revolutionary. For while slavery is as old as humanity, abolitionism is a relatively recent phenomenon that did not emerge until the ideas and ideals of the Enlightenment nurtured it into existence. The Recovering is interested in resonance, or in what Jamison calls the ‘chorus’ – other voices, other narratives of both illness and recovery – and what they might offer to other people suffering or in pain. Resonance, she insists, isn’t ‘the same as conflation’ and doesn’t ‘mean pretending we’[ve] all lived the same thing.’ It’s not about ‘perfect correspondence’ but about ‘the possibility of company’, about fellowship, perhaps, or the realisation that our experiences are so often shared, that they aren’t ever unique, and that it’s precisely this commonality that makes them important. ‘Every addiction,’ she writes, ‘lives at the intersection between public and private experience.’ So too, perhaps, every illness, every bodily injury, everything that changes the way in which we are in the world.

The Recovering is interested in resonance, or in what Jamison calls the ‘chorus’ – other voices, other narratives of both illness and recovery – and what they might offer to other people suffering or in pain. Resonance, she insists, isn’t ‘the same as conflation’ and doesn’t ‘mean pretending we’[ve] all lived the same thing.’ It’s not about ‘perfect correspondence’ but about ‘the possibility of company’, about fellowship, perhaps, or the realisation that our experiences are so often shared, that they aren’t ever unique, and that it’s precisely this commonality that makes them important. ‘Every addiction,’ she writes, ‘lives at the intersection between public and private experience.’ So too, perhaps, every illness, every bodily injury, everything that changes the way in which we are in the world. The Overstory displays some of the formal and stylistic ingenuity we have come to expect from a Richard Powers novel, from his acoustically adventurous prose to his multiple, intertwined narratives (even more multiple in this novel), so characterizing it as purely “agitprop” would be neither fair nor accurate, although the novel is certainly transparent enough in its effort to promote environmental mindfulness. And since Powers has always been willing to take on the weightiest of subjects, generally treated in an earnestly sincere manner, it would go too far to call The Overstory sentimental, although the passages invoking its characters’ often rapturous appreciation of the trees that threaten to replace the characters themselves as the novel’s true dramatis personae are surely full of passionate intensity.

The Overstory displays some of the formal and stylistic ingenuity we have come to expect from a Richard Powers novel, from his acoustically adventurous prose to his multiple, intertwined narratives (even more multiple in this novel), so characterizing it as purely “agitprop” would be neither fair nor accurate, although the novel is certainly transparent enough in its effort to promote environmental mindfulness. And since Powers has always been willing to take on the weightiest of subjects, generally treated in an earnestly sincere manner, it would go too far to call The Overstory sentimental, although the passages invoking its characters’ often rapturous appreciation of the trees that threaten to replace the characters themselves as the novel’s true dramatis personae are surely full of passionate intensity. The received view of Smith is as the founding father of laissez-faire economics (the institute that bears his name certainly provided intellectual fuel to the laissez-faire policies of Margaret Thatcher). But as Norman – mostly correctly – argues, this is wrong, or at least an incomplete view. His goal is to round it out. He is not engaged, however, in just an intellectual exercise. He is battling for the soul of modern conservatism and he wants Smith on his side.

The received view of Smith is as the founding father of laissez-faire economics (the institute that bears his name certainly provided intellectual fuel to the laissez-faire policies of Margaret Thatcher). But as Norman – mostly correctly – argues, this is wrong, or at least an incomplete view. His goal is to round it out. He is not engaged, however, in just an intellectual exercise. He is battling for the soul of modern conservatism and he wants Smith on his side. On August 1943, the sales team at

On August 1943, the sales team at  When Masih Alinejad was a girl in the tiny Iranian village of Ghomikola, her father — who eked out a living selling chickens, ducks and eggs — once brought home a thick yellow stick. Her mother, the village tailor, cut it into six tiny pieces at her husband’s instruction. Each child got one, including the youngest, our author. The yellow stick was a banana, a fruit that the poor family had never seen or tasted. Alinejad, the rebel of the lot, didn’t listen when told to throw the skin away; she sneaked it to school the next day to show off to her friends.

When Masih Alinejad was a girl in the tiny Iranian village of Ghomikola, her father — who eked out a living selling chickens, ducks and eggs — once brought home a thick yellow stick. Her mother, the village tailor, cut it into six tiny pieces at her husband’s instruction. Each child got one, including the youngest, our author. The yellow stick was a banana, a fruit that the poor family had never seen or tasted. Alinejad, the rebel of the lot, didn’t listen when told to throw the skin away; she sneaked it to school the next day to show off to her friends. She got away with it, but the episode was a precursor of what is to come; hers is a life of rebellions big and small followed by ignominious and sometimes draconian punishments. At 18, Alinejad, who would ultimately rise from her humble beginnings to become one of Iran’s top journalists, is carried off to prison. She has been stealing books and carrying on with a ragtag group of feverish ideologues whose crime is printing pamphlets calling for greater dissent in Iranian society. It is enough to get them all arrested.

She got away with it, but the episode was a precursor of what is to come; hers is a life of rebellions big and small followed by ignominious and sometimes draconian punishments. At 18, Alinejad, who would ultimately rise from her humble beginnings to become one of Iran’s top journalists, is carried off to prison. She has been stealing books and carrying on with a ragtag group of feverish ideologues whose crime is printing pamphlets calling for greater dissent in Iranian society. It is enough to get them all arrested. On September 22, 2017, a tiny but energetic particle pierced Earth’s atmosphere and smashed into the planet near the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica. The collision set loose a second particle, which lit a blue streak through the clear ice.

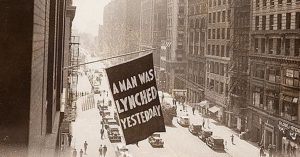

On September 22, 2017, a tiny but energetic particle pierced Earth’s atmosphere and smashed into the planet near the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica. The collision set loose a second particle, which lit a blue streak through the clear ice. The word ‘lynching’, which has recently flooded our newspapers, has an American

The word ‘lynching’, which has recently flooded our newspapers, has an American  One afternoon in the spring of 2015, a senior State Department official named Frank Lowenstein paged through a government briefing book and noticed a map that he had never seen before. Lowenstein was the Obama Administration’s special envoy on Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, a position that exposed him to hundreds of maps of the West Bank. (One adorned his State Department office.)

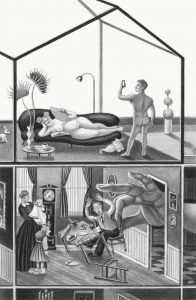

One afternoon in the spring of 2015, a senior State Department official named Frank Lowenstein paged through a government briefing book and noticed a map that he had never seen before. Lowenstein was the Obama Administration’s special envoy on Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, a position that exposed him to hundreds of maps of the West Bank. (One adorned his State Department office.) WHAT DO WE LOSE WHEN WE LOSE OUR PRIVACY?

WHAT DO WE LOSE WHEN WE LOSE OUR PRIVACY? O

O Still, signs of considerable inner turbulence beneath the unruffled surface Powell presented to the world were there. He suffered from nearly permanent insomnia (‘In my early days I never slept a wink’), late on installing a camp bed by his desk so as not to keep his wife awake too. Prey not only to bouts of paralysing accidie, ‘the feeling that nothing’s worth doing’, but to spells of black depression – after an unsuccessful sortie to Hollywood in 1937, and in still more acute form, on returning to civilian life again after the war, when ‘every morning he wished he were dead’ – in his memoirs he implied a rather different explanation for having nothing to say when asked about his character, observing that ‘not everyone can stand the strain of gazing down too long into the personal crater, with its scene of Hieronymus Bosch activities taking place in the depths.’ Spurling, tacitly treating his depressions as discrete episodes, without much bearing on what he may have been like at some deeper level, does not recall this graphic image. Reluctance to venture much psychological surmise after Powell landed in London is visible in other ways. Reporting his claim never to have raised his voice again after leaving Eton, she later shows he was not so imperturbable: ‘rage and frustration’ at the tedium and inanity of life in the army ‘drove him to the kind of explosion he had witnessed as a child from his father’; he ‘lost control’ after Graham Greene’s obstruction of his book on Aubrey; he was hopelessly drunk with ‘unguarded anger, bitterness and shock’ on dismissal as literary editor at Punch; he severed his long-standing ties with the Daily Telegraph in ‘grief and rage’ at infantile barbs from the junior Waugh.

Still, signs of considerable inner turbulence beneath the unruffled surface Powell presented to the world were there. He suffered from nearly permanent insomnia (‘In my early days I never slept a wink’), late on installing a camp bed by his desk so as not to keep his wife awake too. Prey not only to bouts of paralysing accidie, ‘the feeling that nothing’s worth doing’, but to spells of black depression – after an unsuccessful sortie to Hollywood in 1937, and in still more acute form, on returning to civilian life again after the war, when ‘every morning he wished he were dead’ – in his memoirs he implied a rather different explanation for having nothing to say when asked about his character, observing that ‘not everyone can stand the strain of gazing down too long into the personal crater, with its scene of Hieronymus Bosch activities taking place in the depths.’ Spurling, tacitly treating his depressions as discrete episodes, without much bearing on what he may have been like at some deeper level, does not recall this graphic image. Reluctance to venture much psychological surmise after Powell landed in London is visible in other ways. Reporting his claim never to have raised his voice again after leaving Eton, she later shows he was not so imperturbable: ‘rage and frustration’ at the tedium and inanity of life in the army ‘drove him to the kind of explosion he had witnessed as a child from his father’; he ‘lost control’ after Graham Greene’s obstruction of his book on Aubrey; he was hopelessly drunk with ‘unguarded anger, bitterness and shock’ on dismissal as literary editor at Punch; he severed his long-standing ties with the Daily Telegraph in ‘grief and rage’ at infantile barbs from the junior Waugh.