by Niall Chithelen

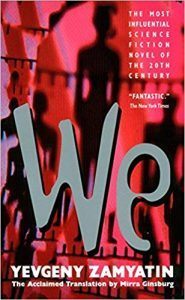

A number of scenes in Eugene Zamyatin’s dystopian novel We (1921) echo moments from Alexander Bogdanov’s utopian Red Star (1908). Bogdanov was a Bolshevik when he wrote Red Star (he was expelled from the party some years before the Russian Revolution), and his “red star” was a socialist, wonderfully technocratic Mars whose residents are preparing to export revolution back to Earth. Zamyatin, also once an Old Bolshevik, wrote in the disturbing aftermath of the Russian Revolution, and his We takes place on a future Earth, ruled over by the United State. It is possible to read We as a response to Red Star and its intellectual moment, with Zamyatin flipping Bogdanov’s Bolshevik idealism to reflect the fright of Bolshevik reality. Bogdanov sought a sort of Communist technocracy, and Zamyatin sensed its enormity, feared it. But, while the two books do offer different political conclusions, the authors seem to share an important belief in humanity and its imperfections, as they provide rather similar answers to a fundamental question of their genre: what kind of freedom do we really need? Read more »

A number of scenes in Eugene Zamyatin’s dystopian novel We (1921) echo moments from Alexander Bogdanov’s utopian Red Star (1908). Bogdanov was a Bolshevik when he wrote Red Star (he was expelled from the party some years before the Russian Revolution), and his “red star” was a socialist, wonderfully technocratic Mars whose residents are preparing to export revolution back to Earth. Zamyatin, also once an Old Bolshevik, wrote in the disturbing aftermath of the Russian Revolution, and his We takes place on a future Earth, ruled over by the United State. It is possible to read We as a response to Red Star and its intellectual moment, with Zamyatin flipping Bogdanov’s Bolshevik idealism to reflect the fright of Bolshevik reality. Bogdanov sought a sort of Communist technocracy, and Zamyatin sensed its enormity, feared it. But, while the two books do offer different political conclusions, the authors seem to share an important belief in humanity and its imperfections, as they provide rather similar answers to a fundamental question of their genre: what kind of freedom do we really need? Read more »

It must be hard for

It must be hard for  In 1961, Piero Manzoni created his most famous art work—ninety small, sealed tins, titled “Artist’s Shit.” Its creation was said to be prompted by Manzoni’s father, who owned a canning factory, telling his son, “Your work is shit.” Manzoni intended “Artist’s Shit” in part as a commentary on consumerism and the obsession we have with artists. As Manzoni put it, “If collectors really want something intimate, really personal to the artist, there’s the artist’s own shit.”

In 1961, Piero Manzoni created his most famous art work—ninety small, sealed tins, titled “Artist’s Shit.” Its creation was said to be prompted by Manzoni’s father, who owned a canning factory, telling his son, “Your work is shit.” Manzoni intended “Artist’s Shit” in part as a commentary on consumerism and the obsession we have with artists. As Manzoni put it, “If collectors really want something intimate, really personal to the artist, there’s the artist’s own shit.” As the EU struggles to rein in some member states that are backsliding on democratic standards, a critical vote in the European Parliament next week could be a decisive moment.

As the EU struggles to rein in some member states that are backsliding on democratic standards, a critical vote in the European Parliament next week could be a decisive moment. On a late Friday afternoon in November last year,

On a late Friday afternoon in November last year,  In a

In a  It could all go wrong in an instant. In Yasmina Reza’s unsettling new novel, Elisabeth, the narrator, looks back on an evening in a Paris suburb that began in the most ordinary way — a casual evening party for family, friends and neighbors — and ended in catastrophe. The nature of the disaster unfolds across a brisk 200 pages, but it is foreshadowed from the very beginning, when Elisabeth observes her neighbor, Jean-Lino, rigid in an uncomfortable chair, surrounded by the detritus of the festivities, “all the leavings of the party arranged in an optimistic moment. Who can determine the starting point of events?”

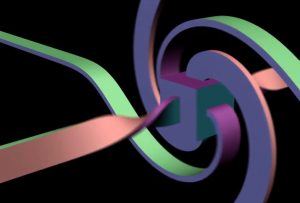

It could all go wrong in an instant. In Yasmina Reza’s unsettling new novel, Elisabeth, the narrator, looks back on an evening in a Paris suburb that began in the most ordinary way — a casual evening party for family, friends and neighbors — and ended in catastrophe. The nature of the disaster unfolds across a brisk 200 pages, but it is foreshadowed from the very beginning, when Elisabeth observes her neighbor, Jean-Lino, rigid in an uncomfortable chair, surrounded by the detritus of the festivities, “all the leavings of the party arranged in an optimistic moment. Who can determine the starting point of events?” Imagine winding the hour hand of a clock back from 3 o’clock to noon. Mathematicians have long known how to describe this rotation as a simple multiplication: A number representing the initial position of the hour hand on the plane is multiplied by another constant number. But is a similar trick possible for describing rotations through space? Common sense says yes, but William Hamilton, one of the most prolific mathematicians of the 19th century, struggled for more than a decade to find the math for describing rotations in three dimensions. The unlikely solution led him to the third of just four number systems that abide by a close analog of standard arithmetic and helped spur the rise of modern algebra.

Imagine winding the hour hand of a clock back from 3 o’clock to noon. Mathematicians have long known how to describe this rotation as a simple multiplication: A number representing the initial position of the hour hand on the plane is multiplied by another constant number. But is a similar trick possible for describing rotations through space? Common sense says yes, but William Hamilton, one of the most prolific mathematicians of the 19th century, struggled for more than a decade to find the math for describing rotations in three dimensions. The unlikely solution led him to the third of just four number systems that abide by a close analog of standard arithmetic and helped spur the rise of modern algebra. On February 22, 2012, when the British photojournalist Paul Conroy survived the artillery barrage that

On February 22, 2012, when the British photojournalist Paul Conroy survived the artillery barrage that  The human mind wants to worry. This is not necessarily a bad thing — after all, if a bear is stalking you, worrying about it may well save your life. Although most of us don’t need to lose too much sleep over bears these days, modern life does present plenty of other reasons for concern: terrorism, climate change, the rise of A.I., encroachments on our privacy, even the apparent decline of international cooperation.

The human mind wants to worry. This is not necessarily a bad thing — after all, if a bear is stalking you, worrying about it may well save your life. Although most of us don’t need to lose too much sleep over bears these days, modern life does present plenty of other reasons for concern: terrorism, climate change, the rise of A.I., encroachments on our privacy, even the apparent decline of international cooperation. The notion of mattering is intimately linked with the notion of attention. To say that something matters is to assert that attention is due it, the kind of attention that both recognises and reveals its reality. Something that matters has a nature that demands to be known, and the knowledge may yield other attitudes and behaviour due it. If I say that something doesn’t matter, I’m saying that it’s not worth paying attention to.

The notion of mattering is intimately linked with the notion of attention. To say that something matters is to assert that attention is due it, the kind of attention that both recognises and reveals its reality. Something that matters has a nature that demands to be known, and the knowledge may yield other attitudes and behaviour due it. If I say that something doesn’t matter, I’m saying that it’s not worth paying attention to. Can a melody provide us with pleasure? Plato certainly thought so, as do many today. But it’s incredibly difficult to discern just how this comes to pass. Is it something about the flow and shape of a tune that encourages you to predict its direction and follow along? Or is it that the lyrics of a certain song describe a scene that reminds you of a joyful time? Perhaps the melody is so familiar that you’ve simply come to identify with it.

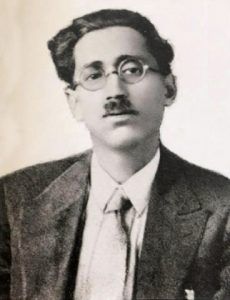

Can a melody provide us with pleasure? Plato certainly thought so, as do many today. But it’s incredibly difficult to discern just how this comes to pass. Is it something about the flow and shape of a tune that encourages you to predict its direction and follow along? Or is it that the lyrics of a certain song describe a scene that reminds you of a joyful time? Perhaps the melody is so familiar that you’ve simply come to identify with it. Mirza Azeem Baig Chughtai has been maligned, misunderstood and pigeonholed as a humourist — which indeed he was; his short stories ‘Yakka’ and ‘Al Shizri’ have been immortalised by the rendition of the legendary Zia Mohyeddin. But other erroneous theories about him have also been made. In ‘Literary Notes: Azeem Baig Chughtai, Sadomasochist or Playful Humourist?’ published in Dawn on Aug 22, 2016, for example, Rauf Parekh considered speculation by literary stalwarts Dr Muhammad Sadiq and Dr Vazeer Agha who believed Chughtai suffered from “depression” and was a “sadomasochist”. Not so. The tantalising title of the piece aside, Parekh rightfully stated that these writers were being “perhaps, all too unsympathetic.”

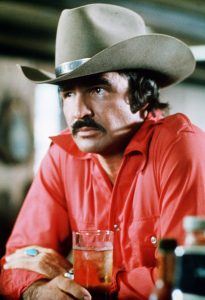

Mirza Azeem Baig Chughtai has been maligned, misunderstood and pigeonholed as a humourist — which indeed he was; his short stories ‘Yakka’ and ‘Al Shizri’ have been immortalised by the rendition of the legendary Zia Mohyeddin. But other erroneous theories about him have also been made. In ‘Literary Notes: Azeem Baig Chughtai, Sadomasochist or Playful Humourist?’ published in Dawn on Aug 22, 2016, for example, Rauf Parekh considered speculation by literary stalwarts Dr Muhammad Sadiq and Dr Vazeer Agha who believed Chughtai suffered from “depression” and was a “sadomasochist”. Not so. The tantalising title of the piece aside, Parekh rightfully stated that these writers were being “perhaps, all too unsympathetic.” For pop-culture enthusiasts of the seventies and eighties, reports of the death of Burt Reynolds, at age eighty-two, of a heart attack, in Jupiter, Florida, may have come as an unexpected shock. Some of us imagined him as eternally youthful, wisecracking, knowingly amused. Reynolds was a genial presence who seemed to have it all—in his heyday, he was the country’s top box-office star for five years; later, he lived in a sprawling estate called Valhalla—and remain a good sport. (His memoir, from 2015, is called “But Enough About Me.”) He was an amiable king of machismo, hairy chests, and highway-focussed buddy comedies, and his friendly sexiness—onscreen and on the covers of tabloids and glossy magazines—was for many years a constant. His groundbreaking

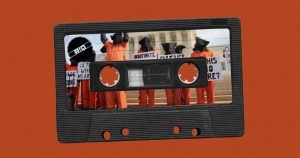

For pop-culture enthusiasts of the seventies and eighties, reports of the death of Burt Reynolds, at age eighty-two, of a heart attack, in Jupiter, Florida, may have come as an unexpected shock. Some of us imagined him as eternally youthful, wisecracking, knowingly amused. Reynolds was a genial presence who seemed to have it all—in his heyday, he was the country’s top box-office star for five years; later, he lived in a sprawling estate called Valhalla—and remain a good sport. (His memoir, from 2015, is called “But Enough About Me.”) He was an amiable king of machismo, hairy chests, and highway-focussed buddy comedies, and his friendly sexiness—onscreen and on the covers of tabloids and glossy magazines—was for many years a constant. His groundbreaking  One of the more unusual methods employed by US interrogators to break the will of detainees during harsh interrogation at Abu Ghraib, Bagram, Mosul, and elsewhere is the use of loud music. The 2006 edition of the US Army’s field manual for interrogation advocated the use of abusive sound as a method of interrogation, a practice corroborated by former detainees who were subject to this abuse. At Guantánamo, inmates reported being held in chains without food or water in total darkness “with loud rap or heavy metal blaring for weeks at a time.” This music played several roles during interrogation. It provoked fear, distress, and disorientation, crowding out the thoughts of the detainee and bending their will to the interrogators’. Even when played at excruciatingly high volume (often as loud as 100 decibels during harsh interrogation, the equivalent of a jackhammer), music leaves no marks on detainees and sheds no blood; it inflicts severe physical and psychological pain without betraying any evidence of its source.

One of the more unusual methods employed by US interrogators to break the will of detainees during harsh interrogation at Abu Ghraib, Bagram, Mosul, and elsewhere is the use of loud music. The 2006 edition of the US Army’s field manual for interrogation advocated the use of abusive sound as a method of interrogation, a practice corroborated by former detainees who were subject to this abuse. At Guantánamo, inmates reported being held in chains without food or water in total darkness “with loud rap or heavy metal blaring for weeks at a time.” This music played several roles during interrogation. It provoked fear, distress, and disorientation, crowding out the thoughts of the detainee and bending their will to the interrogators’. Even when played at excruciatingly high volume (often as loud as 100 decibels during harsh interrogation, the equivalent of a jackhammer), music leaves no marks on detainees and sheds no blood; it inflicts severe physical and psychological pain without betraying any evidence of its source.