https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5NqhSXhlmlw

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5NqhSXhlmlw

Geenen et al in Africa is a country:

How can arts respond to conflict, human rights violations and impunity? What role can they play in peace building and reconciliation? These questions are raised by Milo Rau’s Congo Tribunal, a multimedia project, consisting of a film, a book, a website, a 3D installation, an exhibition in The Hague and, most centrally, a performance that took place in Bukavu and Berlin. The project has an ambitious bottomline: “where politics fail, only art can take over.” The failure of politics, in this case, lie in the blatant impunity and perpetuation of the violence that engulfs eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) since more than twenty years. Milo Rau is very explicit in his political aims, stating:

How can arts respond to conflict, human rights violations and impunity? What role can they play in peace building and reconciliation? These questions are raised by Milo Rau’s Congo Tribunal, a multimedia project, consisting of a film, a book, a website, a 3D installation, an exhibition in The Hague and, most centrally, a performance that took place in Bukavu and Berlin. The project has an ambitious bottomline: “where politics fail, only art can take over.” The failure of politics, in this case, lie in the blatant impunity and perpetuation of the violence that engulfs eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) since more than twenty years. Milo Rau is very explicit in his political aims, stating:

as a reaction to the passivity of the international community to the systematic attacks against the civil population, [the tribunal] was designed to counteract the decades of impunity in the region.

In the film, footage from the hearings in Berlin is mixed with images from Mutarule, Twangiza and Bisie, the cases under investigation, but the bulk of the film reports on the Bukavu hearings. In this eastern Congolese town, a three-day fictitious tribunal was set up, bringing together various actors of the Congolese conflict, including the victims, witnesses, civil society, opposition and government actors as well as other observers. Victims and human rights advocates spoke out about the role of government and the UN in massacres, about conflict minerals and forced displacement, divided into the three aforementioned cases.

More here.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The long-time host of Radio Open Source, Christopher Lydon, joins Abhinandan Sekhri on this special edition of NL Hafta. Lydon talks about how the idea of putting the radio on the Internet came about when he created Radio on the Internet in 2003. He also talks about his stint at The New York Times and starting a national show based in Boston, The Connection. Abhinandan asks Lydon about his views on religion and the art of interviewing. Lydon shares his experience of growing up in an Irish Catholic family.

The conversation pans around a host of other topics: the Iraq war, Media versus Trump in the US and why Lydon doesn’t interview people he dislikes. This and a lot more. Listen up.

Mychal Denzel Smith at Bookforum:

On the Other Side of Freedom is filled with short bursts of this kind of beauty. In service of what, though? In twelve chapters covering organizing, identity, activism, and more, Mckesson sets out to provide an “intellectual, pragmatic political framework for a new liberation movement.”But he doesn’t move much beyond poetic rhapsodizing about protest, which he romanticizes to the exclusion of most other aspects of resistance. Indeed, he’s outright dismissive of some. In the chapter “On Organizing,” he recounts his frustrations at a training session led by a national organizer, which wasn’t, he felt, useful to the situation in Ferguson. This could have been a great opportunity to describe new directions that activism might take, but his description of the meeting’s shortcomings are frustratingly vague. He is unhappy with the notion of the “top-down model in which an organizing body or institution confers knowledge, gives direction, grants permission.” The protesters, he points out, don’t need this kind of guidance—they already possess the skills necessary for effective activism. “The tactics that were effective in bringing about change in the sixties, seventies, and eighties are well known to all,” he explains. “And thus we needed new tactics for a new time.” And what are those new tactics? “To ignore the role of social media as difference-maker in organizing is perilous.”

On the Other Side of Freedom is filled with short bursts of this kind of beauty. In service of what, though? In twelve chapters covering organizing, identity, activism, and more, Mckesson sets out to provide an “intellectual, pragmatic political framework for a new liberation movement.”But he doesn’t move much beyond poetic rhapsodizing about protest, which he romanticizes to the exclusion of most other aspects of resistance. Indeed, he’s outright dismissive of some. In the chapter “On Organizing,” he recounts his frustrations at a training session led by a national organizer, which wasn’t, he felt, useful to the situation in Ferguson. This could have been a great opportunity to describe new directions that activism might take, but his description of the meeting’s shortcomings are frustratingly vague. He is unhappy with the notion of the “top-down model in which an organizing body or institution confers knowledge, gives direction, grants permission.” The protesters, he points out, don’t need this kind of guidance—they already possess the skills necessary for effective activism. “The tactics that were effective in bringing about change in the sixties, seventies, and eighties are well known to all,” he explains. “And thus we needed new tactics for a new time.” And what are those new tactics? “To ignore the role of social media as difference-maker in organizing is perilous.”

more here.

Patrick Blanchfield in n + 1:

[Bob] Woodward has never been a very good writer, but his literary failures have never been more apparent than in Fear, where the mismatch between the prose and the protagonists is almost avant-garde. Many sentences are overwrought to the point of being nonsensical. (“The first act of the Bannon drama is his appearance—the old military field jacket over multiple tennis polo shirts. The second act is his demeanor—aggressive, certain and loud.”) His reliance on cliché is laughable, particularly in his descriptions of characters with whom all of the book’s readers are already well-acquainted. Kellyanne Conway is “feisty” and Reince Priebus—a source whom Woodward conspicuously flatters—is an “empire builder.” Mohammed bin Salman is “charming” and has “vision, energy,” which suggests Woodward has been reading Tom Friedman columns. Jared Kushner has a “self-possessed, almost aristocratic bearing” (possibly the most self-evidently false detail in a book full of them). And the late John McCain is (of course) “outspoken” and a “maverick.” Woodward seems to have a fascination with the bodies and demeanor of older, military men: both Jim Mattis and H.R. McMaster have “ramrod-straight posture,” and the latter is described as “high and tight,” even though he is conspicuously bald. Trump goes “through the roof” twice in a single chapter. And so on.

[Bob] Woodward has never been a very good writer, but his literary failures have never been more apparent than in Fear, where the mismatch between the prose and the protagonists is almost avant-garde. Many sentences are overwrought to the point of being nonsensical. (“The first act of the Bannon drama is his appearance—the old military field jacket over multiple tennis polo shirts. The second act is his demeanor—aggressive, certain and loud.”) His reliance on cliché is laughable, particularly in his descriptions of characters with whom all of the book’s readers are already well-acquainted. Kellyanne Conway is “feisty” and Reince Priebus—a source whom Woodward conspicuously flatters—is an “empire builder.” Mohammed bin Salman is “charming” and has “vision, energy,” which suggests Woodward has been reading Tom Friedman columns. Jared Kushner has a “self-possessed, almost aristocratic bearing” (possibly the most self-evidently false detail in a book full of them). And the late John McCain is (of course) “outspoken” and a “maverick.” Woodward seems to have a fascination with the bodies and demeanor of older, military men: both Jim Mattis and H.R. McMaster have “ramrod-straight posture,” and the latter is described as “high and tight,” even though he is conspicuously bald. Trump goes “through the roof” twice in a single chapter. And so on.

More here.

Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb at the Poetry Foundation:

One week last month, when it was unseasonably cold and rainy—which I loved because I was in a depression—there were suddenly mice flurrying everywhere in the courtyard, in and out of a pneumatic HVAC unit they installed last summer. The mice seemed extra small. Maybe they were babies. Maybe it was because two summers ago we had raccoons in the yard. Then last summer, rats, and a few roaches.

One week last month, when it was unseasonably cold and rainy—which I loved because I was in a depression—there were suddenly mice flurrying everywhere in the courtyard, in and out of a pneumatic HVAC unit they installed last summer. The mice seemed extra small. Maybe they were babies. Maybe it was because two summers ago we had raccoons in the yard. Then last summer, rats, and a few roaches.

A black walnut tree I hadn’t noticed before fell in a storm, against our old building, breaking no windows. I wondered, when I started to see the mice, if their nest had been in the stump. For a couple of days they ran very happily, or so it seemed, along the insulated tubes, and once I watched one try to climb up the slick steel slope of the pneumatic machine. The longer I watched it, the tinier it seemed, the size of a strawberry. It tumbled down on its back like a kid in a blooper video, helpless, limbs flailing, comic and adorable. The mulch was wet, everyone was sweating, and a mossy patina was sprawling slowly across the concrete panels of the courtyard floor.

More here.

Alexander C. R. Hammond in Human Progress:

Norman Ernest Borlaug was an American agronomist and humanitarian born in Iowa in 1914. After receiving a PhD from the University of Minnesota in 1944, Borlaug moved to Mexico to work on agricultural development for the Rockefeller Foundation. Although Borlaug’s taskforce was initiated to teach Mexican farmers methods to increase food productivity, he quickly became obsessed with developing better (i.e., higher-yielding and pest-and-climate resistant) crops.

Norman Ernest Borlaug was an American agronomist and humanitarian born in Iowa in 1914. After receiving a PhD from the University of Minnesota in 1944, Borlaug moved to Mexico to work on agricultural development for the Rockefeller Foundation. Although Borlaug’s taskforce was initiated to teach Mexican farmers methods to increase food productivity, he quickly became obsessed with developing better (i.e., higher-yielding and pest-and-climate resistant) crops.

As Johan Norberg notes in his 2016 book Progress:

“After thousands of crossing of wheat, Borlaug managed to come up with a high-yield hybrid that was parasite resistant and wasn’t sensitive to daylight hours, so it could be grown in varying climates. Importantly it was a dwarf variety, since tall wheat expended a lot of energy growing inedible stalks and collapsed when it grew too quickly. The new wheat was quickly introduced all over Mexico.”

In fact, by 1963, 95 percent of Mexico’s wheat was Borlaug’s variety and Mexico’s wheat harvest grew six times larger than it had been when he first set foot in the country nineteen years earlier.

More here.

A book excerpt and interview with Walter Scheidel, author of “The Great Leveler” in The Economist:

In an age of widening inequality, Walter Scheidel believes he has cracked the code on how to overcome it. In “The Great Leveler”, the Stanford professor posits that throughout history, economic inequality has only been rectified by one of the “Four Horsemen of Leveling”: warfare, revolution, state collapse and plague.

In an age of widening inequality, Walter Scheidel believes he has cracked the code on how to overcome it. In “The Great Leveler”, the Stanford professor posits that throughout history, economic inequality has only been rectified by one of the “Four Horsemen of Leveling”: warfare, revolution, state collapse and plague.

So are liberal democracies doomed to a repeat of the pattern that saw the gilded age give way to a breakdown of society? Or can they legislate a way out of the ominous cycle of brutal inequality and potential violence?

“For more substantial levelling to occur, the established order needs to be shaken up,” he says. “The greater the shock to the system, the easier it becomes to reduce privilege at the top.” Yet nothing is inevitable, and Mr Scheidel urges that society become “more creative” in devising policies that can be implemented. The Economist’s Open Future initiative asked Mr Scheidel to reply to five questions. An excerpt from the book appears thereafter.

More here.

Rowan Moore at The Guardian:

So he sets off, offering the things Sinclair fans will know well: the rhythms of urban walks that turn into sentences and paragraphs, the tracing and retracing of old and new ground, the eternal return to the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor that he has been performing since his Lud Heat of 1975, long before Peter Ackroyd got in on the act. Also the cadences of mordancy and mortality, the attraction to putrefaction. The streets and walls of Sinclair City have the odour and texture of things found floating on canals, but are iridescent with unexpected beauty.

So he sets off, offering the things Sinclair fans will know well: the rhythms of urban walks that turn into sentences and paragraphs, the tracing and retracing of old and new ground, the eternal return to the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor that he has been performing since his Lud Heat of 1975, long before Peter Ackroyd got in on the act. Also the cadences of mordancy and mortality, the attraction to putrefaction. The streets and walls of Sinclair City have the odour and texture of things found floating on canals, but are iridescent with unexpected beauty.

Here again is a personal universe composed of deep knowledge of the arcana of London, of flirtations with the occult, a circle – if that’s not too regular a geometric term – of intriguing and irregular acquaintances. At the same time, he tilts his familiar preoccupations towards the book’s assigned theme.

more here.

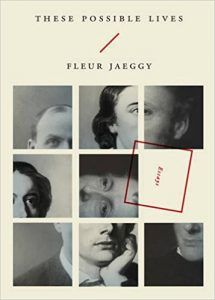

Alan Kitchen at The Quarterly Conversation:

Consider Oliver Munday’s striking cover for These Possible Lives, one of the slim, sharp, dark works of Swiss/Italian author Fleur Jaeggy. The tile motif, bearing eight gray, equal segments from historical portraits of the book’s subjects, is immediately captivating; one glimpses mouths and eyes, poignant gazes into a mercurial unknown, or unsettling direct eye contact that seems to say, there are truths within this small book, but whose truth may they be? This obfuscation is furthered by Munday’s decision to create a ninth tile without image, choosing instead a tilted red box containing that imprecise, strange word, “Essays.” I pick up the book, read the title, These Possible Lives, and think to myself, what is possible about historically recorded lives. A simple red backslash wants to point me down, to the broken mosaic of possibility below, however, I realize red warns, and the indirect backslash conveys hesitation. This cover does a wonderful job trying to dissuade one from any clear preconceptions of the text within, while equally stoking my intense curiosity.

Consider Oliver Munday’s striking cover for These Possible Lives, one of the slim, sharp, dark works of Swiss/Italian author Fleur Jaeggy. The tile motif, bearing eight gray, equal segments from historical portraits of the book’s subjects, is immediately captivating; one glimpses mouths and eyes, poignant gazes into a mercurial unknown, or unsettling direct eye contact that seems to say, there are truths within this small book, but whose truth may they be? This obfuscation is furthered by Munday’s decision to create a ninth tile without image, choosing instead a tilted red box containing that imprecise, strange word, “Essays.” I pick up the book, read the title, These Possible Lives, and think to myself, what is possible about historically recorded lives. A simple red backslash wants to point me down, to the broken mosaic of possibility below, however, I realize red warns, and the indirect backslash conveys hesitation. This cover does a wonderful job trying to dissuade one from any clear preconceptions of the text within, while equally stoking my intense curiosity.

more here.

Sian Cain in The Guardian:

The manuscript for My Life With John Steinbeck, by the author’s second wife and mother of his two children, has been in Montgomery, My Life With John Steinbeck recalls a troubled marriage that spanned 1943 to 1948, a period in which he would write classics including Cannery Row and The Pearl. During their marriage, Conger Steinbeck described a husband who was emotionally distant and demanding. “Like so many writers, he had several lives, and in each he was spoilt, and in each he felt he was king,” she wrote. “From the time John awoke to the time he went to bed, I had to be his slave.”

The manuscript for My Life With John Steinbeck, by the author’s second wife and mother of his two children, has been in Montgomery, My Life With John Steinbeck recalls a troubled marriage that spanned 1943 to 1948, a period in which he would write classics including Cannery Row and The Pearl. During their marriage, Conger Steinbeck described a husband who was emotionally distant and demanding. “Like so many writers, he had several lives, and in each he was spoilt, and in each he felt he was king,” she wrote. “From the time John awoke to the time he went to bed, I had to be his slave.”

Conger Steinbeck first met the author as a nightclub singer in 1938, when he was married to his first wife, Carol Henning. In 1941, Conger Steinbeck alleges that the author sat her down with Henning and told them both: “Whichever of you ladies needs me the most and wants me the most, then that’s the woman I’m going to have.” Describing their wedding night, Conger Steinbeck recalls one “Lady M” ringing their bedroom and speaking to the author for more than an hour on the phone. Conger Steinbeck alludes to Lady M being his mistress, writing that the pair had a “matinee about three times a week”. By her account, Steinbeck rarely showed affection to her or their two sons, Thomas and John Jr, and had never wanted any children. When she was experiencing problems during her pregnancy with John Jr, Steinbeck told her that she had “complicated” his life during a busy period of writing. When John Jr arrived prematurely in 1946, she recalls Steinbeck telling her: “I wish to Christ he’d die, he’s taking up too much of your fucking time.” She identifies the conversation as “the moment when love died”.

More here.

Andrew Sullivan in The New York Times:

It isn’t until you start reading it that you realize how much we need a book like this one at this particular moment. “These Truths,” by Jill Lepore — a professor at Harvard and a staff writer at The New Yorker — is a one-volume history of the United States, constructed around a traditional narrative, that takes you from the 16th to the 21st century. It tries to take in almost everything, an impossible task, but I’d be hard-pressed to think she could have crammed more into these 932 highly readable pages. It covers the history of political thought, the fabric of American social life over the centuries, classic “great man” accounts of contingencies, surprises, decisions, ironies and character, and the vivid experiences of those previously marginalized: women, African-Americans, Native Americans, homosexuals. It encompasses interesting takes on democracy and technology, shifts in demographics, revolutions in economics and the very nature of modernity. It’s a big sweeping book, a way for us to take stock at this point in the journey, to look back, to remind us who we are and to point to where we’re headed.

It isn’t until you start reading it that you realize how much we need a book like this one at this particular moment. “These Truths,” by Jill Lepore — a professor at Harvard and a staff writer at The New Yorker — is a one-volume history of the United States, constructed around a traditional narrative, that takes you from the 16th to the 21st century. It tries to take in almost everything, an impossible task, but I’d be hard-pressed to think she could have crammed more into these 932 highly readable pages. It covers the history of political thought, the fabric of American social life over the centuries, classic “great man” accounts of contingencies, surprises, decisions, ironies and character, and the vivid experiences of those previously marginalized: women, African-Americans, Native Americans, homosexuals. It encompasses interesting takes on democracy and technology, shifts in demographics, revolutions in economics and the very nature of modernity. It’s a big sweeping book, a way for us to take stock at this point in the journey, to look back, to remind us who we are and to point to where we’re headed.

This is not an account of relentless progress. It’s much subtler and darker than that. It reminds us of some simple facts so much in the foreground that we must revisit them: “Between 1500 and 1800, roughly two and a half million Europeans moved to the Americas; they carried 12 million Africans there by force; and as many as 50 million Native Americans died, chiefly of disease. … Taking possession of the Americas gave Europeans a surplus of land; it ended famine and led to four centuries of economic growth.” Nothing like this had ever happened in world history; and nothing like it is possible again. The land was instantly a refuge for religious dissenters, a new adventure in what we now understand as liberalism and a brutal exercise in slave labor and tyranny. It was a vast, exhilarating frontier and a giant, torturing gulag at the same time. Over the centuries, in Lepore’s insightful telling, it represented a giant leap in productivity for humankind: “Slavery was one kind of experiment, designed to save the cost of labor by turning human beings into machines. Another kind of experiment was the invention of machines powered by steam.” It was an experiment in the pursuit of happiness, but it was in effect the pursuit of previously unimaginable affluence.

More here.

Justin E. H. Smith in Art in America:

There are images on the walls of caves, whether we put them there or not. Or, more precisely, we create images on the walls of caves, whether with charcoal and manganese or simply with our imaginations. Michelangelo’s well-known claim that he simply released from stone what was already there is straightforwardly true of Paleolithic artists. They placed their lines where the contours already suggested animal motion.

There are images on the walls of caves, whether we put them there or not. Or, more precisely, we create images on the walls of caves, whether with charcoal and manganese or simply with our imaginations. Michelangelo’s well-known claim that he simply released from stone what was already there is straightforwardly true of Paleolithic artists. They placed their lines where the contours already suggested animal motion.

When I had occasion to remark early in my cave-art education that the pair of clay bison sculptures (ca. 15,500 years before the present) located in France’s Tuc d’Audoubert cave are relative rarities, since most cave art is painted on the walls, a veteran of the field corrected me. “It’s all sculpture,” she said. It is all “sculpture,” though most of it was done for us by the same natural forces that brought forth the underground spaces hosting the works. The caverns’ many undulations, outcroppings, fissures, and declivities were then enhanced by human hands, and sometimes saliva: as in the common crachis technique of spitting on a surface and then rubbing on the pigments. Other techniques include using water or plant oils as mediums and applying colors by means of pads, brushes, hands, or blowing—either through a tube or directly from the mouth.

More here.

Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

In the 1940s, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department began trying to move bighorns back into their historic habitats. Those relocations continue today, and they’ve been increasingly successful at restoring the extirpated herds. But the lost animals aren’t just lost bodies. Their knowledge also died with them—and that is not easily replaced.

In the 1940s, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department began trying to move bighorns back into their historic habitats. Those relocations continue today, and they’ve been increasingly successful at restoring the extirpated herds. But the lost animals aren’t just lost bodies. Their knowledge also died with them—and that is not easily replaced.

Bighorn sheep, for example, migrate. They’ll climb for dozens of miles over mountainous terrain in the spring, “surfing” the green waves of newly emerged plants. They learn the best routes from one another, over decades and generations. And for that reason, a bighorn sheep that’s released into unfamiliar terrain is an ecological noob. It’s not the same as an individual that lived in that place its whole life and was led through it by a knowledgeable mother.

More here.

John Naughton in The Guardian:

One of the biggest puzzles about our current predicament with fake news and the weaponisation of social media is why the folks who built this technology are so taken aback by what has happened. Exhibit A is the founder of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, whose political education I recently chronicled. But he’s not alone. In fact I’d say he is quite representative of many of the biggest movers and shakers in the tech world. We have a burgeoning genre of “OMG, what have we done?” angst coming from former Facebook and Google employees who have begun to realise that the cool stuff they worked on might have had, well, antisocial consequences.

Put simply, what Google and Facebook have built is a pair of amazingly sophisticated, computer-driven engines for extracting users’ personal information and data trails, refining them for sale to advertisers in high-speed data-trading auctions that are entirely unregulated and opaque to everyoneexcept the companies themselves.

The purpose of this infrastructure was to enable companies to target people with carefully customised commercial messages and, as far as we know, they are pretty good at that. (Though some advertisers are beginning to wonder if these systems are quite as good as Google and Facebook claim.) And in doing this, Zuckerberg, Google co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin and co wrote themselves licences to print money and build insanely profitable companies.

It never seems to have occurred to them that their advertising engines could also be used to deliver precisely targeted ideological and political messages to voters.

More here.

Adam Tooze at the LRB:

‘If we don’t do this, we may not have an economy on Monday,’ the chairman of the US Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, said on 18 September 2008 when he demanded action from Congress to assist the banking system. Ten years later we do still have an economy. But it is worth asking whether the panic back then foreclosed other ways forward. In that terrible autumn a decade ago, the first priority was survival. To sit back and let nature take its course was to court disaster, as the collapse of Lehman Brothers proved. The bailouts were ugly, but it would have required a particular kind of fanaticism to dissociate oneself from the rescue effort and accept the risk of catastrophe. Yet in Trump, Brexit and the rise of nationalism across much of Western Europe, are we not seeing the political consequences? Was the crisis an opportunity missed? If there was a single figure whose ideas seemed pertinent in that deeply ambiguous moment, it was John Maynard Keynes. The implosion of the financial system vindicated him against his critics, who had declared markets self-stabilising and government intervention counterproductive. With trade, investment and consumption collapsing and millions cast into unemployment, the world was desperate for fiscal stimulus, and there were calls on all sides for greater controls on banking and financial markets. Keynes is the godfather of policy activism, but, as Geoff Mann argues in his brilliant book In the Long Run We Are All Dead, he is also the best hope of those who want to keep the show on the road by whatever means necessary. He promised both the avoidance of disaster and the preservation of the status quo.

‘If we don’t do this, we may not have an economy on Monday,’ the chairman of the US Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, said on 18 September 2008 when he demanded action from Congress to assist the banking system. Ten years later we do still have an economy. But it is worth asking whether the panic back then foreclosed other ways forward. In that terrible autumn a decade ago, the first priority was survival. To sit back and let nature take its course was to court disaster, as the collapse of Lehman Brothers proved. The bailouts were ugly, but it would have required a particular kind of fanaticism to dissociate oneself from the rescue effort and accept the risk of catastrophe. Yet in Trump, Brexit and the rise of nationalism across much of Western Europe, are we not seeing the political consequences? Was the crisis an opportunity missed? If there was a single figure whose ideas seemed pertinent in that deeply ambiguous moment, it was John Maynard Keynes. The implosion of the financial system vindicated him against his critics, who had declared markets self-stabilising and government intervention counterproductive. With trade, investment and consumption collapsing and millions cast into unemployment, the world was desperate for fiscal stimulus, and there were calls on all sides for greater controls on banking and financial markets. Keynes is the godfather of policy activism, but, as Geoff Mann argues in his brilliant book In the Long Run We Are All Dead, he is also the best hope of those who want to keep the show on the road by whatever means necessary. He promised both the avoidance of disaster and the preservation of the status quo.

more here.