Category: Recommended Reading

Oscar: A Life

Anthony Quinn in The Guardian:

Physically unprepossessing – overgrown, clumsy, “slab-faced” – he was nonetheless a magnetic presence, and in his fledgling days in London as high priest of the aesthetic movement he endured chaffing with “remarkable nonchalance”. One gets here the sense of the young Wilde’s talent to annoy as much as to amuse. James Whistler, from whom he learned the art of self-advertisement, eventually turned on him (he had taught his protege too well). To Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Swinburne, his other heroes, he was an upstart and a “nobody”. On his year-long lecture tour of the US he didn’t always meet with acclaim, or even a civil welcome – a woman in Washington advised him to “wear your hair shorter and your trousers longer”. Back in London he made an advantageous marriage to Constance Lloyd, an heiress, sired two boys and gravitated to the centre of society’s “swirl and whirl”, borne on his gift for talk and his burgeoning talent as a playwright. Arguably the turning points of his life were twofold: his meeting in 1886 with Robbie Ross, who initiated him in homosexual desire and the dangerous enchantments of a double life, and his later introduction to Alfred Douglas, AKA Bosie, whose vicious feud with his father, the 9th Marquess of Queensberry, became the millstones between which Wilde was helplessly ground to dust.

Physically unprepossessing – overgrown, clumsy, “slab-faced” – he was nonetheless a magnetic presence, and in his fledgling days in London as high priest of the aesthetic movement he endured chaffing with “remarkable nonchalance”. One gets here the sense of the young Wilde’s talent to annoy as much as to amuse. James Whistler, from whom he learned the art of self-advertisement, eventually turned on him (he had taught his protege too well). To Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Swinburne, his other heroes, he was an upstart and a “nobody”. On his year-long lecture tour of the US he didn’t always meet with acclaim, or even a civil welcome – a woman in Washington advised him to “wear your hair shorter and your trousers longer”. Back in London he made an advantageous marriage to Constance Lloyd, an heiress, sired two boys and gravitated to the centre of society’s “swirl and whirl”, borne on his gift for talk and his burgeoning talent as a playwright. Arguably the turning points of his life were twofold: his meeting in 1886 with Robbie Ross, who initiated him in homosexual desire and the dangerous enchantments of a double life, and his later introduction to Alfred Douglas, AKA Bosie, whose vicious feud with his father, the 9th Marquess of Queensberry, became the millstones between which Wilde was helplessly ground to dust.

The story of his fall continues to hold and haunt, enclosing as it does a double mystery. The first is his devotion to Douglas, whose cruelty, recklessness and near-insane bouts of rage threatened to alienate Wilde for good yet never did. Can it be explained? Cyril Connolly thought it was exactly Bosie’s failings – “this invulnerable rival egotism” – that kept Wilde on the hook. He may be right. The second is the enigma of Wilde’s refusal to flee once Queensberry and his hired detectives had him cold and a conviction surely beckoned. “Everyone wants me to go abroad,” said Wilde, seeing no use, “unless one is a missionary…or a commercial traveller”. Sturgis thinks there was a strain of defiance in his staying put, though “inertia” probably contributed, too. He may have been resigned to his fate and become “almost an observer of his own catastrophe”.

More here.

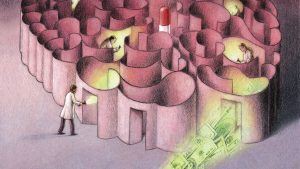

The Alzheimer’s gamble

Jocelyn Kaiser in Science:

When molecular biologist Darren Baker was winding up his postdoc studying cancer and aging a few years ago at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, he faced dispiritingly low odds of winning a National Cancer Institute grant to launch his own lab. A seemingly unlikely area, however, beckoned: Alzheimer’s disease. The U.S. government had begun to ramp up research spending on the neurodegenerative condition, which is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States and will afflict an estimated 14 million people in this country by 2050. “There was an incentive to do some exploratory work,” Baker recalls.

When molecular biologist Darren Baker was winding up his postdoc studying cancer and aging a few years ago at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, he faced dispiritingly low odds of winning a National Cancer Institute grant to launch his own lab. A seemingly unlikely area, however, beckoned: Alzheimer’s disease. The U.S. government had begun to ramp up research spending on the neurodegenerative condition, which is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States and will afflict an estimated 14 million people in this country by 2050. “There was an incentive to do some exploratory work,” Baker recalls.

Baker’s postdoc studies had focused on cellular senescence, the cellular version of aging, which had not yet been linked to Alzheimer’s. But when he gave a drug that kills senescent cells to mice genetically engineered to develop an Alzheimer’s-like illness, the animals suffered less memory loss and fewer of the brain changes that are hallmarks of the disease. Last year, those data helped Baker win his first independent National Institutes of Health (NIH) research grant—not from NIH’s National Cancer Institute, which he once expected to rely on, but from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) in Bethesda, Maryland. He now has a six-person lab at the Mayo Clinic, working on senescence and Alzheimer’s.

Baker is the kind of newcomer NIH hoped to attract with its recent Alzheimer’s funding bonanza. For years, patient advocates have pointed to the growing toll and burgeoning costs of Alzheimer’s as the U.S. population ages. Spurred by those projections and a controversial national goal to effectively treat the disease by 2025, Congress has over 3 years tripled NIH’s annual budget for Alzheimer’s and related dementias, to $1.9 billion. The growth spurt isn’t over: Two draft 2019 spending bills for NIH would bring the total to $2.3 billion—more than 5% of NIH’s overall budget.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Angelitos Negros

In the film, both parents are Mexicans as white as

a Gitano’s bolero sung by an indigena accompanied by the Moor’s guitar

bleached by this American continent’s celluloid in 1948

when in America the world’s colors were polarized into black & blanco.

In the film, Pedro Infante plays Jose Carlos and sings

Angelitos Negros in a chapel, the film’s title song,

asking the painter of the church’s art to paint a picture with black angels

who look like Jose Carlos’s dark-skinned daughter, a child his wife refuses to accept.

¿Pintor, si pintas con amor, porque desprecias su color

si sabes que en el cielo también los quiere Dios?

Tonight I sing the same song for my morenos absent from these cathedral walls:

O painter, painting with a foreign brush to the rumba of its old bolero.

Listen to our angel’s chorus of inocentes morenos muertos.

We morenos in the barrio create a gumbo quilombo, our little taste of heaven

with matches and propane and coal stones under a pot of cabra y culebras.

We morenos are brown turned black, burnt by fire fired from guardia guns

looking to make us congos for a legisladore’s chanchudos.

Listen to los pelaos in the favelas kicking

around the soccer ball de pie a pie de pie a pie de pie a pie cabeza cabeza

gol!

forced out of their homes by a world class stadium they can never afford to get into,

forced into a life in the prison of their streets.

They too deserve to be painted, pintor, in your fresco Adoration scenes.

¿Pintor, si pintas con amor, porque desprecias su color?

Eartha Kitt sings Pintame Angelitos Negros,

the same Andrés Eloy Blanco poem Infante set to song

on thrift store vinyl playing in homemade YouTube clips.

Kitt raises her voice high enough

to swallow morning if it does not give her a sky

with dark-skinned angels in its clouds tonight.

Then dusk falls over the continent built on

shadows, shackles, and shame.

Broken-winged Blackbird three shades of jade, just fly into dark matter in outer space.

Perhaps up there is a better painter, better god for us all to obey.

by Darrel Alejandro Holnes

from Split This Rock

Tuesday, October 2, 2018

Nobel Prize In Physics 2018: How To Make Ultra-Intense Ultra-Short Laser Pulses

Chad Orzel in Forbes:

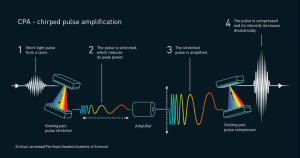

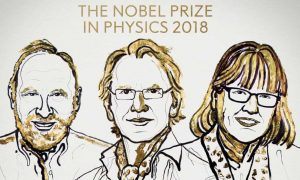

The 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics was announced this morning “for groundbreaking inventions in the field of laser physics.” This is really two half-prizes, though: one to Arthur Ashkin for the development of “optical tweezers” that use laser light to move small objects around, and the other to Gérard Mourou and Donna Strickland for the development of techniques to make ultra-short, ultra-intense laser pulses. These are both eminently Nobel-worthy, but really aren’t all that closely related, so I’m going to split talking about them into two separate posts; this first one will deal with the Mourou and Strickland half, because I suspect it’s the less immediately comprehensible of the two, and thus probably needs more unpacking.

The 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics was announced this morning “for groundbreaking inventions in the field of laser physics.” This is really two half-prizes, though: one to Arthur Ashkin for the development of “optical tweezers” that use laser light to move small objects around, and the other to Gérard Mourou and Donna Strickland for the development of techniques to make ultra-short, ultra-intense laser pulses. These are both eminently Nobel-worthy, but really aren’t all that closely related, so I’m going to split talking about them into two separate posts; this first one will deal with the Mourou and Strickland half, because I suspect it’s the less immediately comprehensible of the two, and thus probably needs more unpacking.

What Mourou and Strickland did was to develop a method for boosting the intensity and reducing the duration of pulses from a pulsed laser. This plays a key role in all manner of techniques that need really high intensity light, from eye surgery to laser-based acceleration of charged particles (sometimes touted as a tool for next-generation particle accelerators), or really fast pulses of light such as recent experiments looking at how long it takes to knock an electron out of a molecule. This kind of enabling of other science is exactly the kind of thing that the Nobel Prize ought to recognize and support, so I think this is a great choice for a prize.

More here.

Deborah Eisenberg, Chronicler of American Insanity

Giles Harvey in the New York Times:

It takes Deborah Eisenberg about a year to write a short story. She works at a desk overlooking the gently curving stairwell in her spacious, light-soaked Chelsea apartment. A small painting of a brick wall, suspended from the high ceiling by two slender cables, hangs at eye level in front of the desk, a sardonic reminder of the nature of her task. For Eisenberg, coming up against a brick wall is what writing often feels like. At 72, she has been conducting her siege on the ineffable for more than four decades, and yet the creative process remains almost totally opaque to her. “You work and you work and you work and you work,” she told me recently, her delicate, quavering voice an audible testament to the endless hours of labor. “And for months or years on end, you’re just a total dray horse, and then you finally finish something, and the next day you look at it and you think, How did that get there? What is that? Why were those the things that I seemed to need to say?”

It takes Deborah Eisenberg about a year to write a short story. She works at a desk overlooking the gently curving stairwell in her spacious, light-soaked Chelsea apartment. A small painting of a brick wall, suspended from the high ceiling by two slender cables, hangs at eye level in front of the desk, a sardonic reminder of the nature of her task. For Eisenberg, coming up against a brick wall is what writing often feels like. At 72, she has been conducting her siege on the ineffable for more than four decades, and yet the creative process remains almost totally opaque to her. “You work and you work and you work and you work,” she told me recently, her delicate, quavering voice an audible testament to the endless hours of labor. “And for months or years on end, you’re just a total dray horse, and then you finally finish something, and the next day you look at it and you think, How did that get there? What is that? Why were those the things that I seemed to need to say?”

Behind her desk is a wrought-iron daybed on which she takes frequent breaks to read; while she’s in the early stages of working on a new story, two hours of writing a day is usually as much as she can manage. When I asked her what she does with the rest of her time, a puzzled look came across her face, as though she were trying to decipher some hidden message in the ceiling moldings. “It’s hard to say,” she eventually conceded.

More here.

Noam Chomsky: I just visited Lula, the world’s most prominent political prisoner

Noam Chomsky in The Intercept:

Prisons are reminiscent of Tolstoy’s famous observation about unhappy families: Each “is unhappy in its own way,” though there are some common features — for prisons, the grim and stifling recognition that someone else has total authority over your life.

Prisons are reminiscent of Tolstoy’s famous observation about unhappy families: Each “is unhappy in its own way,” though there are some common features — for prisons, the grim and stifling recognition that someone else has total authority over your life.

My wife Valeria and I have just visited a prison to see arguably the most prominent political prisoner of today, a person of unusual significance in contemporary global politics.

By the standards of U.S. prisons I’ve seen, the Federal Prison in Curitiba, Brazil, is not formidable or oppressive — though that is a rather low bar. It is nothing like the few I’ve visited abroad — not remotely like Israel’s Khiyam torture chamber in southern Lebanon, later bombed to dust to efface the crime, and a very long way from the unspeakable horrors of Pinochet’s Villa Grimaldi, where the few who survived the exquisitely designed series of tortures were tossed into a tower to rot — one of the means to ensure that the first neoliberal experiment, under the supervision of leading Chicago economists, could proceed without disruptive voices.

Nonetheless, it is a prison.

More here.

Fascinating talk by Frank Abagnale, whose story was told in Steven Spielberg’s movie “Catch Me If You Can”

Physics Nobel prize won by Arthur Ashkin, Gérard Mourou and Donna Strickland

Ian Sample and Nicola Davis in The Guardian:

Three scientists have been awarded the 2018 Nobel prize in physics for creating groundbreaking tools from beams of light.

Three scientists have been awarded the 2018 Nobel prize in physics for creating groundbreaking tools from beams of light.

The American physicist Arthur Ashkin, Gérard Mourou from France, and Donna Strickland in Canada will share the 9m Swedish kronor (£770,000) prize announced by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm on Tuesday. Strickland is the first female physics laureate for 55 years.

Ashkin, an affiliate of Bell Laboratories in New Jersey, wins half of the prize for his development of “optical tweezers”, a tractor beam-like technology that allows scientists to grab atoms, viruses and bacteria in finger-like laser-beams. The effect was demonstrated by the award committee by levitating a ping pong ball with a hairdryer.

Mourou at the École Polytechnique near Paris, and Strickland at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, each receive a quarter of the prize for work that paved the way for the shortest, most intense laser beams ever created. Their technique, named chirped pulse amplification, is now used in laser machining and enables doctors to perform millions of corrective laser eye surgeries every year.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Lazarus in Varanasi

FROM A PYRE on the burning ghat

a corpse slowly sits up in the flames.

As if remembering something important.

As if to look around one more time.

As if he has something at last to say.

As if there might be a way out of this

.

by Joseph Stroud

from Narrative Magazine

Winter 2008

As if remembering something important.

As if to look around one more time.

As if he has something at last to say.

As if there might be a way out of this

.

by Joseph Stroud

from Narrative Magazine

Winter 2008

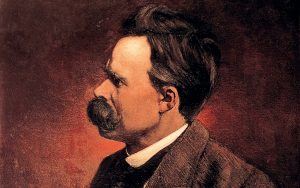

The agony and the destiny: Friedrich Nietzsche’s descent into madness

Ray Monk in New Statesman:

The Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann told a story of how, in 1952, just two years after publishing his ground-breaking book, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, he visited the Cambridge philosopher CD Broad at Trinity College. During their conversation, Broad mentioned someone by the name of Salter. Was that, Kaufmann asked, the Salter who had written a book on Nietzsche? “Dear no,” Broad replied, “he did not deal with crackpot subjects like that; he wrote about psychical research.” In the years immediately before, during and just after the Second World War, Nietzsche’s reputation in the English-speaking world was at its lowest, largely owing to the fact that his work had been, with the support of his virulently anti-Semitic sister Elisabeth, appropriated by the Nazis. In their hands, Nietzsche’s notion of the Übermensch (I prefer to use the original German than any of the published translations; “superman” sounds silly, and “beyond-man” and “overman” do not sound like natural English) became associated with notions of Aryan racial superiority, while his idea of the “will to power” was used to justify militarism and authoritarianism.

The Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann told a story of how, in 1952, just two years after publishing his ground-breaking book, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, he visited the Cambridge philosopher CD Broad at Trinity College. During their conversation, Broad mentioned someone by the name of Salter. Was that, Kaufmann asked, the Salter who had written a book on Nietzsche? “Dear no,” Broad replied, “he did not deal with crackpot subjects like that; he wrote about psychical research.” In the years immediately before, during and just after the Second World War, Nietzsche’s reputation in the English-speaking world was at its lowest, largely owing to the fact that his work had been, with the support of his virulently anti-Semitic sister Elisabeth, appropriated by the Nazis. In their hands, Nietzsche’s notion of the Übermensch (I prefer to use the original German than any of the published translations; “superman” sounds silly, and “beyond-man” and “overman” do not sound like natural English) became associated with notions of Aryan racial superiority, while his idea of the “will to power” was used to justify militarism and authoritarianism.

In the chapter on Nietzsche in his History of Western Philosophy, published in 1946, Bertrand Russell went some way towards correcting some of these Nazi-led misunderstandings, emphasising that Nietzsche was far from being a nationalist, a racist, a worshipper of the state, or a German supremacist (his writings are in fact full of anti-German sentiment). Russell, however, could not free himself from his times sufficiently to avoid misrepresenting Nietzsche’s notion of the will to power. Nietzsche’s ethic, Russell claims, can be summed up by saying: “Victors in war, and their descendants, are usually biologically superior to the vanquished. It is therefore desirable that they should hold all the power, and should manage affairs exclusively in their own interests.” Russell’s chapter ends with a statement that has often been quoted and which helped to shape Nietzsche’s reputation among English-speaking people for a generation: “I dislike Nietzsche because he likes the contemplation of pain… because the men whom he most admires are conquerors, whose glory is cleverness in causing men to die.”

More here.

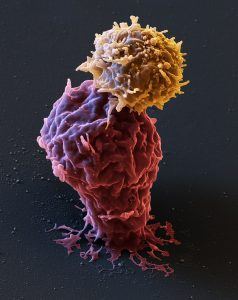

Breakthrough Leukemia Treatment Backfires in a Rare Case

Denise Grady in The New York Times:

A highly unusual death has exposed a weak spot in a groundbreaking cancer treatment: One rogue cell, genetically altered by the therapy, can spiral out of control in a patient and cause a fatal relapse. The treatment, a form of immunotherapy, genetically engineers a patient’s own white blood cells to fight cancer. Sometimes described as a “living drug,” it has brought lasting remissions to leukemia patients who were on the brink of death. Among them is Emily Whitehead, the first child to receive the treatment, in 2012 when she was 6. The treatment does not always work, and side effects can be dangerous, even life-threatening. Doctors have learned to manage them. But in one patient, the therapy seems to have backfired in a previously unknown way. He was 20, with an aggressive type of leukemia. The treatment altered not just his cancer-fighting cells, but also — inadvertently — the genes of one leukemia cell. The genetic change made that cell invisible to the ones that had been programmed to seek and destroy cancer.

A highly unusual death has exposed a weak spot in a groundbreaking cancer treatment: One rogue cell, genetically altered by the therapy, can spiral out of control in a patient and cause a fatal relapse. The treatment, a form of immunotherapy, genetically engineers a patient’s own white blood cells to fight cancer. Sometimes described as a “living drug,” it has brought lasting remissions to leukemia patients who were on the brink of death. Among them is Emily Whitehead, the first child to receive the treatment, in 2012 when she was 6. The treatment does not always work, and side effects can be dangerous, even life-threatening. Doctors have learned to manage them. But in one patient, the therapy seems to have backfired in a previously unknown way. He was 20, with an aggressive type of leukemia. The treatment altered not just his cancer-fighting cells, but also — inadvertently — the genes of one leukemia cell. The genetic change made that cell invisible to the ones that had been programmed to seek and destroy cancer.

The researchers noted that the case confirms a longstanding hypothesis: It takes just one malignant cell to give rise to a deadly cancer. Their report was published on Monday in the journal Nature Medicine. At first, the patient had a complete remission. But at the same time, that single enemy cell was multiplying uncontrollably, into billions of leukemia cells that caused a relapse nine months later and ultimately killed him. His cells were engineered at the University of Pennsylvania, where the treatment, called CAR-T therapy, was developed in collaboration with Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the drug company Novartis. The treatment was experimental, and he was part of a study. Researchers say that the case was a rare event, never seen before, and that there is no evidence of this problem in cells engineered by Novartis, other drug companies or other research centers.

More here.

Monday, October 1, 2018

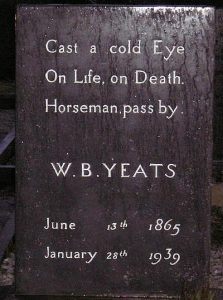

The Nightmare of the Bones

by Thomas O’Dwyer

Drumcliffe churchyard lies in the shadow of a flat-topped mountain, in the western Irish countryside of Sligo county, on the Atlantic coast. There are remains of a round tower and a carved Celtic high cross. It would be the perfect resting place for a country’s greatest poet – especially if the poet himself had chosen it.

Drumcliffe churchyard lies in the shadow of a flat-topped mountain, in the western Irish countryside of Sligo county, on the Atlantic coast. There are remains of a round tower and a carved Celtic high cross. It would be the perfect resting place for a country’s greatest poet – especially if the poet himself had chosen it.

“Bury me up there on the mountain, Roquebrune,” W.B. Yeats wrote to his wife Georgie before his death in France in 1939. “And then, after a year or so, after the newspapers have forgotten, plant me in Sligo.” The poet died in the Hôtel Idéal Séjour in the nearby town of Menton. His funeral cortege did indeed wind up a narrow hill to where Roquebrune cemetery looks out over the Mediterranean. But then came World War II, and the repatriation of the remains of one Irish poet was unlikely to be a priority for the Nazi-occupied French, or anybody else.

Seventy years ago this autumn, this last wish of Ireland’s first Nobel Prize winner was finally fulfilled. His family and proud countrymen brought him home for a splendid state funeral in his beloved Sligo. Yeats had written of his desired resting place before his death in one of his last poems, Under Ben Bulben. “Under bare Ben Bulben’s head / In Drumcliffe churchyard Yeats is laid, / An ancestor was rector there / Long years ago; a church stands near, / By the road an ancient Cross.” For good measure, he added an epitaph, the same one carved on his tombstone. In 1948, on a typical Irish September day, half sunshine and half rain, W.B. Yeats was laid in his chosen place to rest in peace forever.

Or was he? Read more »

Gender egalitarianism made us human: the ‘feminist turn’ in human origins

by Camilla Power

Modern Darwinism, neo-darwinism, aka ‘selfish-gene’ theory is often regarded as deeply politically suspect by social scientists. It’s viewed as a Trojan horse for capitalist ideology as soon as any evolutionary anthropologist or, worse, psychologist, tries to say anything about human beings. But the funny thing is that sociobiology, evolutionary ecology, whatever you want to call it (it keeps changing name because social scientists are so rude about it) has taken an extraordinary feminist turn through this century.

The strategies of females have now become central to models of human origins. Forget ‘man the hunter’, it’s hardworking grandmothers, babysitting apes, children with more than one daddy, who are the new fairytale heroes. Man the mighty hunter comes as a late afterthought. And these are not just lean-in alpha females but collectives in increasingly complex female coalitions, with the idea that the ‘social brain is for females’ extrapolated from primate studies.

Taken together, these models add up to a broad view that gender egalitarianism was not just part of the package but a fundamental aspect of what made us modern humans. They include Kristen Hawkes and colleagues ‘grandmother hypothesis’; Sarah Hrdy’s model of cooperative childcare as matrix of emotional modernity; Steven Beckerman and Paul Valentine’s ‘partible paternity’ model; the rejection of patrilocality as standard for hunter-gatherers by Frank Marlowe, Helen Alvarez, Mark Dyble and colleagues; and the ‘Female cosmetic coalitions’ hypothesis for the emergence of symbolic culture, by myself, Chris Knight and Ian Watts.

Responding to the seminal conference on ‘Man the Hunter’ in the mid-1960s, feminist anthropology of the 1970s began to examine critically whether women’s oppression was a true universal resulting from the sexual division of labour. Read more »

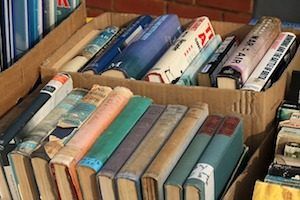

A Potency Of Life

by Mary Hrovat

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year.

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year.

When I walk in and see table after table laden with books and inhale the unmistakable smell of the printed page, I almost always get a sense of the richness of the world and a feeling of optimism about my opportunities for learning about it. Even though I know that in addition to many treasures, the tables also hold things like the 1979 edition of What Color Is Your Parachute?, I still feel the thrill. It reminds me of when I was a teenager and didn’t realize how finite my life is. I was in love with history in particular, and with archaeology, with music and art and astronomy. But I also wanted to learn how to do things: draw, paint, play chess, grow vegetables. Growing up in a family where my mother was often too busy and my father was too distant to teach any of us much beyond the fundamentals of their religion, I thought books could teach me those things too.

The layout at the book fair is always pretty much the same. There are certain tables I visit first, and some I rarely check. I usually have a few specific titles or subject areas in mind: There’s an author I’ve become interested in, or a historical period I’m reading about. I always look for Paul Theroux on the Travel table. Over the better part of a decade, I slowly assembled all eleven volumes of Will and Ariel Durant’s The Story of Civilization and the Norton Anthologies of English and American literature. Read more »

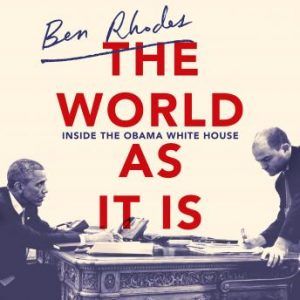

The World as It Was: The World as It Is

by Adele A Wilby

As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.

As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.

Rhodes autobiography operates on two levels of analysis. On the one hand, Rhodes tells the story of his journey to becoming Obama’s Deputy National Security Advisor and speech writer, amongst other positions, and the impact this experience had on his personal development. Plucked from relative obscurity while working in the offices of the Woodrow Wilson International Centre in 2007, Rhodes narrates the challenges, and indeed sacrifices, required of the individual who assumes such an important position in a president’s trusted inner circle. In particular, Rhodes’ story of his work with Obama highlights how, as a speech writer, he was an important figure in communicating Obama’s thoughts and policies to a national and global audience, and his book can be seen as a continuation of that role.

Arguably however, the more significant aspect of Rhodes’ experience was the opportunity his position afforded him to observe the workings, thinking and character of the decision-maker of US foreign and domestic policy, Barack Obama. Consequently, Rhodes provides us with deeper insights into the nuanced thinking and administrative style of Obama. Thus, his book makes an important contribution to many academic disciplines, and furthers our understanding of the personal and political dynamics that underpinned US foreign and domestic decision-making when Obama was at the helm of the US political establishment. Read more »

Poem by Rafiq Kathwari: “Where Are the Snows of Yesteryear?”

An Inconvenient Democracy

by Joshua Wilbur

This past Tuesday—September 25th 2018—was “National Voter Registration Day” in the United States. I didn’t register to vote on September 25th, and I’m not registered to vote as I write this now.

I’m not proud of the fact. Far from it, I feel intensely guilty when I imagine some upstanding acquaintance asking me, “Are you registered to vote yet?”, so that I am forced to stammer through an explanation as to why not. (The alternative in this scenario would be to lie, to simply say “Yes,” which many people do when questioned about voting habits. It is shameful to have done nothing on election day, but, even still, our society imparts no immediate negative consequences on non-voters, and no one knows who actually voted and who did not.)

But I’ll admit it openly: I’m not registered to vote because my printer is out of ink.

You see, I recently moved to a new address in a different state. The county must be made aware of my presence here if I am to be added to the electoral roll. Thirty-seven states allow online voter registration, but, unfortunately, my new home state is not one of them. This means that I must print, complete, and mail a form to the “County Commissioner of Registration” at least twenty-one days prior to Election Day on November 6th.

This is mildly annoying, a minor inconvenience. It doesn’t deserve mention alongside the history of American voter suppression in all its contemptible forms, beginning with poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and literacy tests in the Jim Crow South and persisting in the guises of photo ID laws, district realignment, felony disenfranchisement, and voter purges, to name just a few contemporary tactics.

No one is actively trying to suppress my vote. I have a problem with my printer. I just need to order some ink (and I guess a box of envelopes), print the form, fill out the form, put it in the envelope, seal the envelope, walk a few blocks, and drop it in a mailbox. It really isn’t that difficult. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Hitting The Reset Button

by Max Sirak

One of the things I love about sports is they’re a low-stakes environment in which to practice high-stakes skills. For most people, most of the time, the results of a sporting match don’t affect the long-term quality of their lives. This is what I mean by “low-stakes.” In the grand scheme and scope of our lives, the outcomes of games rarely matter. Which is what makes sports such a great place to practice skills that really can and do impact our lives for the better. This is what I mean by “high-stakes.”

One of the things I love about sports is they’re a low-stakes environment in which to practice high-stakes skills. For most people, most of the time, the results of a sporting match don’t affect the long-term quality of their lives. This is what I mean by “low-stakes.” In the grand scheme and scope of our lives, the outcomes of games rarely matter. Which is what makes sports such a great place to practice skills that really can and do impact our lives for the better. This is what I mean by “high-stakes.”

There are things we can all learn and hone in and through the context of playing or watching sports to help us build happier and healthier lives. Teamwork is one of them. Learning what it means to be part of a team, play well with others, and sacrifice individual accolades for the greater good are all lessons which can be gained and groomed via sports but apply to the larger fields of life.

The graceful handling of victory and defeat is another. Play or watch sports long enough, and you’ll eventually be given opportunities to encounter both ends of this spectrum. You’ll feel what it’s like to win and what sort of behaviors that warm feeling motivates. Likewise, you’ll also brush up against limitations and defeat and be given a chance to explore these colder consolations and the behaviors they motivate.

Working together, getting your way, or not are pretty obvious places where sports mirror life. No revelations here. Which is why I’d like to step away from the surface (whether hardwood, grass, water, ice, or clay…) and take some time to explore a more subtle realm, that of thought. Specifically, how the thoughts you think make you feel. Read more »