Angelitos Negros

In the film, both parents are Mexicans as white as

a Gitano’s bolero sung by an indigena accompanied by the Moor’s guitar

bleached by this American continent’s celluloid in 1948

when in America the world’s colors were polarized into black & blanco.

In the film, Pedro Infante plays Jose Carlos and sings

Angelitos Negros in a chapel, the film’s title song,

asking the painter of the church’s art to paint a picture with black angels

who look like Jose Carlos’s dark-skinned daughter, a child his wife refuses to accept.

¿Pintor, si pintas con amor, porque desprecias su color

si sabes que en el cielo también los quiere Dios?

Tonight I sing the same song for my morenos absent from these cathedral walls:

O painter, painting with a foreign brush to the rumba of its old bolero.

Listen to our angel’s chorus of inocentes morenos muertos.

We morenos in the barrio create a gumbo quilombo, our little taste of heaven

with matches and propane and coal stones under a pot of cabra y culebras.

We morenos are brown turned black, burnt by fire fired from guardia guns

looking to make us congos for a legisladore’s chanchudos.

Listen to los pelaos in the favelas kicking

around the soccer ball de pie a pie de pie a pie de pie a pie cabeza cabeza

gol!

forced out of their homes by a world class stadium they can never afford to get into,

forced into a life in the prison of their streets.

They too deserve to be painted, pintor, in your fresco Adoration scenes.

¿Pintor, si pintas con amor, porque desprecias su color?

Eartha Kitt sings Pintame Angelitos Negros,

the same Andrés Eloy Blanco poem Infante set to song

on thrift store vinyl playing in homemade YouTube clips.

Kitt raises her voice high enough

to swallow morning if it does not give her a sky

with dark-skinned angels in its clouds tonight.

Then dusk falls over the continent built on

shadows, shackles, and shame.

Broken-winged Blackbird three shades of jade, just fly into dark matter in outer space.

Perhaps up there is a better painter, better god for us all to obey.

by Darrel Alejandro Holnes

from Split This Rock

In 2015,

In 2015,  In the wake of Hurricane Florence and the rains that followed, residents of disaster-stricken areas of North Carolina are now also dealing with swarms of “

In the wake of Hurricane Florence and the rains that followed, residents of disaster-stricken areas of North Carolina are now also dealing with swarms of “ Aging — everybody does it, very few people actually do something about it. Coleen Murphy is an exception. In her laboratory at Princeton, she and her team study aging in the famous C. Elegans roundworm, with an eye to extending its lifespan as well as figuring out exactly what processes take place when we age. In this episode we contemplate what scientists have learned about aging, and the prospects for ameliorating its effects — or curing it altogether? — even in human beings.

Aging — everybody does it, very few people actually do something about it. Coleen Murphy is an exception. In her laboratory at Princeton, she and her team study aging in the famous C. Elegans roundworm, with an eye to extending its lifespan as well as figuring out exactly what processes take place when we age. In this episode we contemplate what scientists have learned about aging, and the prospects for ameliorating its effects — or curing it altogether? — even in human beings. A village boy once asked his local priest, “Father, when you go to sleep, where do you lay your beard, under or over your blanket?” Ever since he heard the question, the priest couldn’t sleep through the night. If he laid his beard under the blanket, he felt hot; if his beard was over the blanket, he got cold. He had always slept fine, without waking. But once he was asked to pick a single side, neither one seemed comfortable.

A village boy once asked his local priest, “Father, when you go to sleep, where do you lay your beard, under or over your blanket?” Ever since he heard the question, the priest couldn’t sleep through the night. If he laid his beard under the blanket, he felt hot; if his beard was over the blanket, he got cold. He had always slept fine, without waking. But once he was asked to pick a single side, neither one seemed comfortable. When I first adopted Lucas nine years ago from a cat rescue organization in Washington, D.C., his name was Puck. “Because he’s mischievous,” his foster mother said. Although we changed the name, her analysis proved correct. Unlike his brother Tip, whom I also adopted, a gray cat with white paws and an Eeyore-ish dour doofy sweetness, Lucas was from the start a fierce black fireball, a menace to stray toes or blanket fringes or loose items on tabletops. He was my alarm clock in the morning with his habit of knocking my hairbrush, deodorant, and earrings box off my bureau until I got up to feed him.

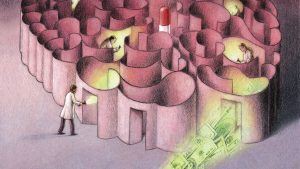

When I first adopted Lucas nine years ago from a cat rescue organization in Washington, D.C., his name was Puck. “Because he’s mischievous,” his foster mother said. Although we changed the name, her analysis proved correct. Unlike his brother Tip, whom I also adopted, a gray cat with white paws and an Eeyore-ish dour doofy sweetness, Lucas was from the start a fierce black fireball, a menace to stray toes or blanket fringes or loose items on tabletops. He was my alarm clock in the morning with his habit of knocking my hairbrush, deodorant, and earrings box off my bureau until I got up to feed him. As former Labor secretary Robert Reich recently noted, Ivy League schools are government-subsidized playgrounds for the rich: “Imagine a system of college education supported by high and growing government spending on elite private universities that mainly educate children of the wealthy and upper-middle class, and low and declining government spending on public universities that educate large numbers of children from the working class and the poor.

As former Labor secretary Robert Reich recently noted, Ivy League schools are government-subsidized playgrounds for the rich: “Imagine a system of college education supported by high and growing government spending on elite private universities that mainly educate children of the wealthy and upper-middle class, and low and declining government spending on public universities that educate large numbers of children from the working class and the poor. Since the 2015 publication of his Pulitzer Prize–winning debut novel The Sympathizer, Viet Thanh Nguyen has emerged as one of the literary world’s leading public intellectuals. At a time of rising xenophobia and anti-refugee sentiment in the United States and elsewhere, Nguyen’s fiction, academic writing, and media commentary remind us of the need to keep telling the stories that drop out of national narratives, and to remember the histories that the powerful would have us forget. In the following conversation with Karl Ashoka Britto, Nguyen discusses literary form and the representation of violence, the complex dynamics of remembering and forgetting, and the possibility of a politics that could be post-communist without being pro-capitalist.

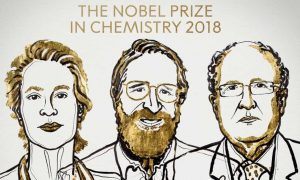

Since the 2015 publication of his Pulitzer Prize–winning debut novel The Sympathizer, Viet Thanh Nguyen has emerged as one of the literary world’s leading public intellectuals. At a time of rising xenophobia and anti-refugee sentiment in the United States and elsewhere, Nguyen’s fiction, academic writing, and media commentary remind us of the need to keep telling the stories that drop out of national narratives, and to remember the histories that the powerful would have us forget. In the following conversation with Karl Ashoka Britto, Nguyen discusses literary form and the representation of violence, the complex dynamics of remembering and forgetting, and the possibility of a politics that could be post-communist without being pro-capitalist. Three scientists have won the Nobel prize in chemistry for their work in harnessing evolution to produce new enzymes and antibodies.

Three scientists have won the Nobel prize in chemistry for their work in harnessing evolution to produce new enzymes and antibodies. Something has gone wrong in the university—especially in certain fields within the humanities. Scholarship based less upon finding truth and more upon attending to social grievances has become firmly established, if not fully dominant, within these fields, and their scholars increasingly bully students, administrators, and other departments into adhering to their worldview. This worldview is not scientific, and it is not rigorous. For many, this problem has been growing increasingly obvious, but strong evidence has been lacking. For this reason, the three of us just spent a year working inside the scholarship we see as an intrinsic part of this problem.

Something has gone wrong in the university—especially in certain fields within the humanities. Scholarship based less upon finding truth and more upon attending to social grievances has become firmly established, if not fully dominant, within these fields, and their scholars increasingly bully students, administrators, and other departments into adhering to their worldview. This worldview is not scientific, and it is not rigorous. For many, this problem has been growing increasingly obvious, but strong evidence has been lacking. For this reason, the three of us just spent a year working inside the scholarship we see as an intrinsic part of this problem. Physically unprepossessing – overgrown, clumsy, “slab-faced” – he was nonetheless a magnetic presence, and in his fledgling days in London as high priest of the aesthetic movement he endured chaffing with “remarkable nonchalance”. One gets here the sense of the young Wilde’s talent to annoy as much as to amuse.

Physically unprepossessing – overgrown, clumsy, “slab-faced” – he was nonetheless a magnetic presence, and in his fledgling days in London as high priest of the aesthetic movement he endured chaffing with “remarkable nonchalance”. One gets here the sense of the young Wilde’s talent to annoy as much as to amuse.  When molecular biologist Darren Baker was winding up his postdoc studying cancer and aging a few years ago at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, he faced dispiritingly low odds of winning a National Cancer Institute grant to launch his own lab. A seemingly unlikely area, however, beckoned: Alzheimer’s disease. The U.S. government had begun to ramp up research spending on the neurodegenerative condition, which is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States and will afflict an estimated 14 million people in this country by 2050. “There was an incentive to do some exploratory work,” Baker recalls.

When molecular biologist Darren Baker was winding up his postdoc studying cancer and aging a few years ago at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, he faced dispiritingly low odds of winning a National Cancer Institute grant to launch his own lab. A seemingly unlikely area, however, beckoned: Alzheimer’s disease. The U.S. government had begun to ramp up research spending on the neurodegenerative condition, which is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States and will afflict an estimated 14 million people in this country by 2050. “There was an incentive to do some exploratory work,” Baker recalls. The

The  It takes Deborah Eisenberg about a year to write a short story. She works at a desk overlooking the gently curving stairwell in her spacious, light-soaked Chelsea apartment. A small painting of a brick wall, suspended from the high ceiling by two slender cables, hangs at eye level in front of the desk, a sardonic reminder of the nature of her task. For Eisenberg, coming up against a brick wall is what writing often feels like. At 72, she has been conducting her siege on the ineffable for more than four decades, and yet the creative process remains almost totally opaque to her. “You work and you work and you work and you work,” she told me recently, her delicate, quavering voice an audible testament to the endless hours of labor. “And for months or years on end, you’re just a total dray horse, and then you finally finish something, and the next day you look at it and you think, How did that get there? What is that? Why were those the things that I seemed to need to say?”

It takes Deborah Eisenberg about a year to write a short story. She works at a desk overlooking the gently curving stairwell in her spacious, light-soaked Chelsea apartment. A small painting of a brick wall, suspended from the high ceiling by two slender cables, hangs at eye level in front of the desk, a sardonic reminder of the nature of her task. For Eisenberg, coming up against a brick wall is what writing often feels like. At 72, she has been conducting her siege on the ineffable for more than four decades, and yet the creative process remains almost totally opaque to her. “You work and you work and you work and you work,” she told me recently, her delicate, quavering voice an audible testament to the endless hours of labor. “And for months or years on end, you’re just a total dray horse, and then you finally finish something, and the next day you look at it and you think, How did that get there? What is that? Why were those the things that I seemed to need to say?” Prisons are reminiscent of Tolstoy’s famous observation about unhappy families: Each “is unhappy in its own way,” though there are some common features — for prisons, the grim and stifling recognition that someone else has total authority over your life.

Prisons are reminiscent of Tolstoy’s famous observation about unhappy families: Each “is unhappy in its own way,” though there are some common features — for prisons, the grim and stifling recognition that someone else has total authority over your life.