Category: Recommended Reading

Tracy K. Smith’s Poetry of Desire

Hilton Als at The New Yorker:

In “Duende” and in her third book, the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Life on Mars” (2011), Smith explores another aspect of her “I”—Tracy before she was Tracy. In “Interrogative,” she writes of her pregnant mother: “What did your hand mean to smooth / Across the casket of your belly? / What echoed there, if not me—tiny body / Afloat, akimbo, awake, or at rest?” To imagine who you were before you were is a way of understanding who you are now and what you may become. Smith is interested in the roots of love, the various selves that go into the making of a body. But “Duende” isn’t all wish and wonder. It’s also about threats to the female body, pleasures that can be withdrawn, judged. In her extraordinary poem “The Searchers,” she writes about a character in John Ford’s 1956 film of the same title—a white girl who was kidnapped and brought up by Native Americans.

In “Duende” and in her third book, the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Life on Mars” (2011), Smith explores another aspect of her “I”—Tracy before she was Tracy. In “Interrogative,” she writes of her pregnant mother: “What did your hand mean to smooth / Across the casket of your belly? / What echoed there, if not me—tiny body / Afloat, akimbo, awake, or at rest?” To imagine who you were before you were is a way of understanding who you are now and what you may become. Smith is interested in the roots of love, the various selves that go into the making of a body. But “Duende” isn’t all wish and wonder. It’s also about threats to the female body, pleasures that can be withdrawn, judged. In her extraordinary poem “The Searchers,” she writes about a character in John Ford’s 1956 film of the same title—a white girl who was kidnapped and brought up by Native Americans.

more here.

Acclaimed Authors Pen Letter in Protest at ‘Forced Resignation’ of Ian Buruma

Ed Pilkington at The Guardian:

Some of the biggest names in English letters, including Joyce Carol Oates, Ian McEwan, Lorrie Morre and Colm Tóibín, have released a joint letter in which they express dismay at what they call the “forced resignation” of the editor of the New York Review of Books under a #MeToo stormcloud.

Some of the biggest names in English letters, including Joyce Carol Oates, Ian McEwan, Lorrie Morre and Colm Tóibín, have released a joint letter in which they express dismay at what they call the “forced resignation” of the editor of the New York Review of Books under a #MeToo stormcloud.

Ian Buruma stepped down from the editorship of America’s most prestigious literary magazine earlier this month in the wake of his decision to publish a highly controversial article by former broadcaster and alleged sex attacker Jian Ghomeshi. The 3,400-word essay, in which Ghomeshi played down allegations of sexual violence brought against him by 20 women as “inaccurate” under the headline Reflections from a Hashtag, kicked up a storm on social media.

more here.

Republicans should drop Kavanaugh now, before they harm themselves for a generation

Dominic Green in Spectator:

Watching Blasey Ford’s opening statement and questioning this morning before an almost entirely male panel, I am more sure than ever that she is telling the truth. Either that, or she is a better character actor than Meryl Streep. There are no serious grounds to believe that this is a case of mistaken identity either. Nothing in Blasey Ford’s demeanour, her statements or her responses suggested that she is doing anything other than telling the truth. Everything about her traumatised manner, her detailed statements and responses has the ring of credibility. As Democratic senator Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island said, her account matches prosecutorial standards of ’preliminary credibility’, and its details are ‘consistent with the known facts’. Everything in Blasey Ford’s account also accords with what everyone who moves in circles associated with ‘elite prep schools’ — and ‘elite’ universities too — knows is a serious problem in male behaviour. The problem has two faces, the entitlement of spoilt princelings, and its supercharging by heavy drinking into forms of dangerous and criminal idiocy. This kind of perverted male camaraderie is not high spirits, unless high spirits is the ‘uproarious laughter’ of two boys as one of them assaults a 15-year old girl.

Watching Blasey Ford’s opening statement and questioning this morning before an almost entirely male panel, I am more sure than ever that she is telling the truth. Either that, or she is a better character actor than Meryl Streep. There are no serious grounds to believe that this is a case of mistaken identity either. Nothing in Blasey Ford’s demeanour, her statements or her responses suggested that she is doing anything other than telling the truth. Everything about her traumatised manner, her detailed statements and responses has the ring of credibility. As Democratic senator Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island said, her account matches prosecutorial standards of ’preliminary credibility’, and its details are ‘consistent with the known facts’. Everything in Blasey Ford’s account also accords with what everyone who moves in circles associated with ‘elite prep schools’ — and ‘elite’ universities too — knows is a serious problem in male behaviour. The problem has two faces, the entitlement of spoilt princelings, and its supercharging by heavy drinking into forms of dangerous and criminal idiocy. This kind of perverted male camaraderie is not high spirits, unless high spirits is the ‘uproarious laughter’ of two boys as one of them assaults a 15-year old girl.

Brett Kavanaugh has denied all and any elements of Blasey Ford’s testimony. So this case, greyed with drink and memory, comes down to a black and white decision. I don’t care whether the winners and losers are liberals or conservatives, or whether they’re men or women. This is a watershed moment, and the responsiveness and credibility of America’s governing institutions are at stake.

Republicans and conservatives have climbed up a tree out of misplaced party loyalty and masculine blind spots. They still have time to climb down. They need to do so quickly, before they confirm every negative stereotype about them. They need to get out of the echo chambers of their social media and the closed rooms of their political strategizing, and understand that they are insulting more than 50 per cent of the electorate. Donald Trump, who routinely insults more than 50 per cent of the electorate, wants to leave a Supreme Court that will lean conservative for years. Kavanaugh is not the only possible conservative nominee for the bench, but he is no longer a credible one. There are bound to be more allegations against him. True or not, they will damage the dignity of the Supreme Court at a time when America needs its institutions to work. If Trump and the Republicans stick with him, they will damage the Court, the presidency and their party. Out of self-interest, if nothing else, they need to drop Kavanaugh before he takes them down with him.

More here.

How cerebral organoids are guiding brain-cancer research and therapies

Anna Nowogrodzki in Nature:

Even in comparison to other types of cancer, brain cancer is particularly deadly. People with glioblastoma multiforme, one of the most common forms of brain cancer, have a median survival of less than 15 months after diagnosis. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has so far approved only five drugs for treating brain cancer. Given this limited range, researchers could search for potential treatments among the wider pool of all FDA-approved drugs; however, any found to be effective would probably work in just a slim percentage of people with brain cancer.

Even in comparison to other types of cancer, brain cancer is particularly deadly. People with glioblastoma multiforme, one of the most common forms of brain cancer, have a median survival of less than 15 months after diagnosis. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has so far approved only five drugs for treating brain cancer. Given this limited range, researchers could search for potential treatments among the wider pool of all FDA-approved drugs; however, any found to be effective would probably work in just a slim percentage of people with brain cancer.

Unfortunately, those with the condition do not have time to cycle through hundreds of drugs to find the one that might work. But if researchers could grow numerous small brain-like structures that contained a replica of the person’s tumour and then bathe them in various treatments, in the space of a few weeks, they might learn exactly which ones would have the best chance of fighting brain cancer in that individual. That’s the vision of Howard Fine, a neuro-oncologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City who is developing such models, known as cerebral organoids, for the study of brain cancer — with the ultimate goal of finding the most appropriate treatment for each person. Organoids are miniature, laboratory-grown versions of the body’s organs. They contain several cell types and have a simplified 3D anatomy. They are particularly valuable for studying brain cancer because neither human brain tumours transplanted into mice nor human tumour stem cells grown in a culture dish behave in the same way as their counterparts in the body. At only five years old, the field of cerebral organoids is still young. Many challenges lie ahead, including how to give these organoids blood vessels, immune cells and a more realistic structure. But Fine and other researchers think that cerebral organoids might provide fresh opportunities for studying how tumours arise, screening drug candidates and developing evidence-based, personalized treatment plans for people with brain cancer.

More here.

Friday Poem

The Sleepers -excerpt

Now I tell what my mother told me today as we sat at

dinner together,

Of when she was a nearly grown girl living home with her

parents on the old homestead.

A red squaw came one breakfast-time to the old homestead,

On her back she carried a bundle of rushes for

rush-bottoming chairs;

Her hair straight shiny coarse black and profuse

half-enveloped her face,

Her step was free and elastic . . . . her voice sounded

exquisitely as she spoke.

My mother looked in delight and amazement at the stranger,

She looked at the beauty of her tall-borne face and full and

pliant limbs,

The more she looked upon her she loved her,

Never before had she seen such wonderful beauty and purity;

She made her sit on a bench by the jamb of the fireplace . . . .

she cooked food for her,

She had no work to give her but she gave her remembrance

and fondness.

The red squaw staid all the forenoon, and toward the middle

of the afternoon she went away;

O my mother was loth to have her go away,

All the week she thought of her . . . . she watched for her

many a month,

She remembered her many a winter and many a summer,

But the red squaw never came nor was heard of there again.

Walt Whitman

from The Sleepers

Thursday, September 27, 2018

Unpublished and Untenured, a Philosopher Inspired a Cult Following

James Ryerson in the New York Times:

Ever since completing his Ph.D. at the University of Pittsburgh in 1993, the Israeli philosopher Irad Kimhi has been building the résumé of an academic failure. After a six-year stint at Yale in the ’90s that did not lead to a permanent job, he has bounced around from school to school, stringing together a series of short-term lectureships and temporary teaching positions in the United States, Europe and Israel. As of June, his curriculum vitae listed no publications to date — not even a journal article. At 60, he remains unknown to most scholars in his field.

Ever since completing his Ph.D. at the University of Pittsburgh in 1993, the Israeli philosopher Irad Kimhi has been building the résumé of an academic failure. After a six-year stint at Yale in the ’90s that did not lead to a permanent job, he has bounced around from school to school, stringing together a series of short-term lectureships and temporary teaching positions in the United States, Europe and Israel. As of June, his curriculum vitae listed no publications to date — not even a journal article. At 60, he remains unknown to most scholars in his field.

Among a circle of philosophers who have worked or interacted with Kimhi, however, he has a towering reputation. His dissertation adviser, Robert Brandom, describes him as “truly brilliant, a deep and original philosopher.” Jonathan Lear, who helped hire Kimhi at Yale, says that to hear Kimhi talk is to experience “living philosophy, the real thing.” The philosopher and physicist David Z. Albert, a close friend of Kimhi’s, calls him “the best and most energetic and most surprising conversationalist I have ever met, a volcano of theories and opinions and provocations about absolutely everything.” (Kimhi and Albert appear to have been inspirations for the two brainy protagonists of Rivka Galchen’s short story“The Region of Unlikeness.”)

To his admirers, Kimhi is a hidden giant, a profound thinker who, because of a personality at once madly undisciplined and obsessively perfectionistic, has been unable to commit his ideas to paper.

More here. [Thanks to Jessica Collins.]

Religion is about emotion regulation, and it’s very good at it

Stephen Asma in Aeon:

Sigmund Freud, who referred to himself as a ‘godless Jew’, saw religion as delusional, but helpfully so. He argued that we humans are naturally awful creatures – aggressive, narcissistic wolves. Left to our own devices, we would rape, pillage and burn our way through life. Thankfully, we have the civilising influence of religion to steer us toward charity, compassion and cooperation by a system of carrots and sticks, otherwise known as heaven and hell.

Sigmund Freud, who referred to himself as a ‘godless Jew’, saw religion as delusional, but helpfully so. He argued that we humans are naturally awful creatures – aggressive, narcissistic wolves. Left to our own devices, we would rape, pillage and burn our way through life. Thankfully, we have the civilising influence of religion to steer us toward charity, compassion and cooperation by a system of carrots and sticks, otherwise known as heaven and hell.

The French sociologist Émile Durkheim, on the other hand, argued in The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1912) that the heart of religion was not its belief system or even its moral code, but its ability to generate collective effervescence: intense, shared experiences that unify individuals into cooperative social groups. Religion, Durkheim argued, is a kind of social glue, a view confirmed by recent interdisciplinary research.

While Freud and Durkheim were right about the important functions of religion, its true value lies in its therapeutic power, particularly its power to manage our emotions.

More here.

Scandal Folder

Anjuli Raza Fatima Kolb at the Poetry Foundation:

I’m not one to go digging around in old dirt, but sometimes you find good bones. Recently I’ve been doing some research in the papers of an important scholar and public intellectual who taught at my university and died on my twenty-second birthday. When he died, I was a baby editor, and bad at my job, but I felt a little grand. I managed to get the day off from work for the memorial and bought a prim looking black dress from Goodwill, linen with a satin ribbon. I dug out my interview heels. People like Noam Chomsky said very moving things, but I couldn’t pay attention. The shape of everyone’s grief was so different and it didn’t really make sense to me. Everyone took his death personally, and the obituary in the Times was less than totally respectful.

I’m not one to go digging around in old dirt, but sometimes you find good bones. Recently I’ve been doing some research in the papers of an important scholar and public intellectual who taught at my university and died on my twenty-second birthday. When he died, I was a baby editor, and bad at my job, but I felt a little grand. I managed to get the day off from work for the memorial and bought a prim looking black dress from Goodwill, linen with a satin ribbon. I dug out my interview heels. People like Noam Chomsky said very moving things, but I couldn’t pay attention. The shape of everyone’s grief was so different and it didn’t really make sense to me. Everyone took his death personally, and the obituary in the Times was less than totally respectful.

Since eye and mind were wandery—like when you’ve crashed a party—I stared and tried to stay very still. I followed the lines of heavy stone to the grand but unbeautiful ceiling, traced the bronchioles of the organ, blinked in slowmo to feel the quiet hubbub, and tried to remember who told me about Alice Babs singing there, in Riverside Church or was it St. John the Divine, and what was supposed to have been shocking about it.

These are hard times for theoryTM, the summer bookended by revelations of a scandal that has split my social world down the middle, largely along generational lines. One of the theorists weighing in—who has signed a letter suggesting that reputation and clout, “grace” and “wit” should be allowed to eclipse abuse—wrote recently “I am still against scandal culture.” It’s probably true that there’s more than a little schadenfreude involved in this #moment. The internet is interested in juicy shit, and this is soggy-ass laundry from an out-of-touch cadre on the intellectual left.

But when Derrida died, and Said died, it’s not like the public was more earnestly interested in what they were up to. People hate theory.

More here.

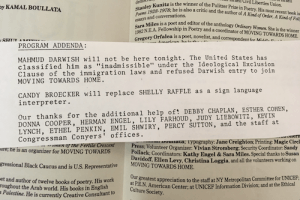

Jeremy Corbyn with Yanis Varoufakis at the Edinburgh Book Festival

Deborah Eisenberg’s Vast Fictions

Minna Zallman Proctor at Bookforum:

These stories are family sagas writ short, a form Eisenberg may well have invented. The word saga generally brings to mind giant, beach-sandy paperbacks, like Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude—not short stories, not even long short stories. Stories don’t in principle have the space to unfurl lifetimes, multiple settings, formation and reverberation. Yet Eisenberg’s stories— with their telescoping time lines and surprising associative turns—expand, even in their ellipses. “Hang on,” thinks young Adam in “Recalculating,” as he considers the earth’s revolution, the chance of it spinning off its axis. “Adam clung to some bits of stubble and closed his eyes. Hang on, he thought, as the Earth gained speed and spun recklessly into the night—hang on, hang on, hang on!” Because Adam is young, his imagination is terrifyingly vivid, and life around him will spin out of control. He will find purchase on stubble in unexpected places, like the girl seeking facts in “Cross Off and Move On.” There is so much living and expression these characters (small and large) bring to the page, lest anyone forget the amplitude.

These stories are family sagas writ short, a form Eisenberg may well have invented. The word saga generally brings to mind giant, beach-sandy paperbacks, like Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude—not short stories, not even long short stories. Stories don’t in principle have the space to unfurl lifetimes, multiple settings, formation and reverberation. Yet Eisenberg’s stories— with their telescoping time lines and surprising associative turns—expand, even in their ellipses. “Hang on,” thinks young Adam in “Recalculating,” as he considers the earth’s revolution, the chance of it spinning off its axis. “Adam clung to some bits of stubble and closed his eyes. Hang on, he thought, as the Earth gained speed and spun recklessly into the night—hang on, hang on, hang on!” Because Adam is young, his imagination is terrifyingly vivid, and life around him will spin out of control. He will find purchase on stubble in unexpected places, like the girl seeking facts in “Cross Off and Move On.” There is so much living and expression these characters (small and large) bring to the page, lest anyone forget the amplitude.

more here.

The Sublimity of the Super-Brat

Rand Richards Cooper at Commonweal:

In the Realm of Perfection dismisses this conventional wisdom and insists that we engage McEnroe on another plane altogether. The inquiry begins in our bemusement at the man-child. When McEnroe interrupts a match to vent, when he spits profane and acid mockery at line judges and referees, when he taunts fans or takes a swat at a photographer with his racquet—the crowd booing lustily—his matches approach the spectacle of professional wrestling, with its travesty of villainy. Why would a player aspire to that?

In the Realm of Perfection dismisses this conventional wisdom and insists that we engage McEnroe on another plane altogether. The inquiry begins in our bemusement at the man-child. When McEnroe interrupts a match to vent, when he spits profane and acid mockery at line judges and referees, when he taunts fans or takes a swat at a photographer with his racquet—the crowd booing lustily—his matches approach the spectacle of professional wrestling, with its travesty of villainy. Why would a player aspire to that?

Faraut quotes a sports psychologist noting that such tantrums are counterproductive for most players. For them, anger of the kind McEnroe displays—tear-your-hair-out anger; threaten-bystanders anger—saps concentration and compromises performance. But not McEnroe. He wasn’t risking his game (nor, as many suspected, was he out to disarm his opponent); he was stoking his game by feeding on bad feelings.

more here.

The Tlatelolco Massacre of 1968

Lorna Scott Fox at The TLS:

So began a utopian experiment in direct democracy, especially remarkable in Mexico’s authoritarian culture, where vertical hierarchies prevailed socially and politically. The encounter between classes was a mutual education: history and theory in exchange for street smarts and live contact with the country’s social problems. As told to Elena Poniatowska for her collection of testimonies Massacre in Mexico(1971; see also the TLS, May 4, 2018), the university students felt duty-bound to enlighten the polytechnicians, droning on about Lenin, Marcuse and imperialism. Impatient IPN delegates would shout out “¡Concretito!”, “Nuts and bolts! Who’s got tomorrow’s posters?” CNH assemblies also saw heated disagreement about tactics and clashes between those of differing political affiliations. The overarching demand for greater civic participation meant the crucial work of consciousness-raising took place in the streets and slums. The IPN was at the forefront of the roving brigadas with their loudspeakers, xeroxed leaflets and newspapers shoved through bus and car windows, and their street theatre and speak-ins that attracted sympathetic crowds and gave people the chance to voice their own complaints.

So began a utopian experiment in direct democracy, especially remarkable in Mexico’s authoritarian culture, where vertical hierarchies prevailed socially and politically. The encounter between classes was a mutual education: history and theory in exchange for street smarts and live contact with the country’s social problems. As told to Elena Poniatowska for her collection of testimonies Massacre in Mexico(1971; see also the TLS, May 4, 2018), the university students felt duty-bound to enlighten the polytechnicians, droning on about Lenin, Marcuse and imperialism. Impatient IPN delegates would shout out “¡Concretito!”, “Nuts and bolts! Who’s got tomorrow’s posters?” CNH assemblies also saw heated disagreement about tactics and clashes between those of differing political affiliations. The overarching demand for greater civic participation meant the crucial work of consciousness-raising took place in the streets and slums. The IPN was at the forefront of the roving brigadas with their loudspeakers, xeroxed leaflets and newspapers shoved through bus and car windows, and their street theatre and speak-ins that attracted sympathetic crowds and gave people the chance to voice their own complaints.

more here.

Three Dreams in the Key of G

Sam Jordison in The Guardian:

Hold tight. Because I’m now going to try to explain what I think is happening in Three Dreams in the Key of G. As the title hints, there are three narrative strands, although they are not particularly dreamy. The first contains the journal entries of Jean Ome, a mother of two children living in Ulster and married to a man who has connections to violent Protestant paramilitaries. These journal entries have been written infrequently and with no definite purpose by an intelligent and frustrated woman trapped by circumstances who is prone to prolixity. Just to make things extra difficult, they have all been muddled up and are presented out of order.

Hold tight. Because I’m now going to try to explain what I think is happening in Three Dreams in the Key of G. As the title hints, there are three narrative strands, although they are not particularly dreamy. The first contains the journal entries of Jean Ome, a mother of two children living in Ulster and married to a man who has connections to violent Protestant paramilitaries. These journal entries have been written infrequently and with no definite purpose by an intelligent and frustrated woman trapped by circumstances who is prone to prolixity. Just to make things extra difficult, they have all been muddled up and are presented out of order.

The second strand is made up of internet messages from Jean Ohm, an equally verbose voice, but one under severe constraint. Ohm supposedly lives in a kind of sanctuary for battered women and claims to have found a way to breed without men – and that she is writing her missives while under siege from the “FBI, DEA, ATF and all manner of sect-obsessed acronyms”.

The third strand is a hectoring Greek chorus, presented by – bear with me – a genome. That’s to say, A, C, T and G: the four letters in the sequence of DNA. This voice is also called the “Creatrix” and its general role is to explain the mysteries of genetics and the hubris of mankind for thinking it can map out such complexities, even though, as the voice reminds us: “You, you don’t even know you’ve been born. How or why.”

More here.

How Doctors Use Poetry

Danny Linggonegoro in Nautilus:

One part of the Hippocratic Oath, the vow taken by physicians, requires us to “remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.” When I, along with my medical school class, recited that oath at my white coat ceremony a year ago, I admit that I was more focused on the biomedical aspects than the “art.” I bought into the mechanism of insulin lowering blood sugar. I bought into the concept of diabetes-induced kidney damage. I bought into the idea of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with diabetes. But art’s—poetry’s—role in the modern practice of medicine? I’ve changed my mind. Physicians are beginning to understand that the role of language and human expression in medicine extends beyond that horizon of uncertainty where doctor and patient must speak to each other about a course of treatment. The restricted language of blood oxygen levels, drug protocols, and surgical interventions may conspire against understanding between doctor and patient—and against healing. As doctors learn to communicate beyond these restrictions, they are reaching for new tools—like poetry.

One part of the Hippocratic Oath, the vow taken by physicians, requires us to “remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.” When I, along with my medical school class, recited that oath at my white coat ceremony a year ago, I admit that I was more focused on the biomedical aspects than the “art.” I bought into the mechanism of insulin lowering blood sugar. I bought into the concept of diabetes-induced kidney damage. I bought into the idea of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with diabetes. But art’s—poetry’s—role in the modern practice of medicine? I’ve changed my mind. Physicians are beginning to understand that the role of language and human expression in medicine extends beyond that horizon of uncertainty where doctor and patient must speak to each other about a course of treatment. The restricted language of blood oxygen levels, drug protocols, and surgical interventions may conspire against understanding between doctor and patient—and against healing. As doctors learn to communicate beyond these restrictions, they are reaching for new tools—like poetry.

Researchers have demonstrated with functional magnetic resonance imaging that reciting poetry engages the primary reward circuitry in the brain, called the mesolimbic pathway. So does music—but, the researchers found, poetry elicited a unique response.1 While the mechanism is unclear, it’s been suggested that poetic, musical, and other nonpharmacologic adjuvant therapies can reduce pain and the use and dosage of opioids.2

More here.

Thursday Poem

Thank You My Fate

Great humility fills me,

great purity fills me,

I make love with my dear

as if I made love dying

as if I made love praying,

tears pour

over my arms and his arms.

I don’t know whether this is joy

or sadness, I don’t understand

what I feel, I’m crying,

I’m crying, it’s humility

as if I were dead,

gratitude, I thank you, my fate,

I’m unworthy, how beautiful

my life.

Anna Swir

from A Book of Luminous Things

Harvest Books, 1996,

translation: Czelaw Milosz

and Leonard Nathan

Wednesday, September 26, 2018

The Last Man to Know Everything

Troy Vettese in the Boston Review:

Mike Davis didn’t write his first book until his forties. He was too busy doing other things, from working in a slaughterhouse to running the Communist Party’s bookshop in Los Angeles (until he, an inveterate Trotskyist, threw out the Soviet cultural attaché). His late start as a scholar, however, has been compensated for by a deep reservoir of experiences to draw from and a swift pen: since writing his first book in 1986, he has published twenty more.

Mike Davis didn’t write his first book until his forties. He was too busy doing other things, from working in a slaughterhouse to running the Communist Party’s bookshop in Los Angeles (until he, an inveterate Trotskyist, threw out the Soviet cultural attaché). His late start as a scholar, however, has been compensated for by a deep reservoir of experiences to draw from and a swift pen: since writing his first book in 1986, he has published twenty more.

Not that he slowed down his extracurricular pursuits after he became a feted scholar. Over the last thirty years he has been a MacArthur and Getty fellow, the urban design commissioner of Pasadena, an advisor to the Crips (the Los Angeles gang), a university lecturer, Los Angeles’s most sought-after tour guide, a journalist, and an author of children’s science fiction. One hopes his latest book, Old Gods, New Enigmas: Marx’s Lost Theory—a disparate collection of four essays on working-class history, nationalism, and the environment—will not be his last; the man needs to write a memoir. The only way to make sense of the new book’s blunderbuss array of topics is to know Davis’s vast scholarly corpus. Composed as it is of various strands drawn from his interests and experiences, which over the years have become ever more complex and tangled, it can only be ordered through intellectual biography.

More here.

The Physics Of Why Timekeeping First Failed In The Americas

Ethan Siegel in Forbes:

For millennia, humanity’s one-and-only reliable way to keep time was based on the Sun. Over the course of a year, the Sun, at any location on Earth, would follow a predictable pattern and path through the sky. Sundials, no more sophisticated than a vertical stick hammered into the ground, were the best timekeeping devices available to our ancestors.

For millennia, humanity’s one-and-only reliable way to keep time was based on the Sun. Over the course of a year, the Sun, at any location on Earth, would follow a predictable pattern and path through the sky. Sundials, no more sophisticated than a vertical stick hammered into the ground, were the best timekeeping devices available to our ancestors.

All of that began to change in the 17th century. Galileo, among others, noted that a pendulum would swing with the same exact period regardless of the amplitude of the swing or the magnitude of the weight at the bottom. Only the length of the pendulum mattered. Within mere decades, pendulums with a period of exactly one second were introduced. For the first time, time could be accurately kept here on Earth, with no reliance on the Sun, the stars, or any other sign from the Universe.

More here.

Howard Zinn’s Anti-Textbook

Sam Wineburg in Slate:

With more than 2 million copies in print, Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United Statesis more than a book. It is a cultural icon. “You wanna read a real history book?” Matt Damon asks his therapist in the 1997 movie Good Will Hunting. “Read Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States. That book’ll … knock you on your ass.” The book’s original gray cover was painted red, white, and blue in 2003 and is now marketed with special displays in suburban megastores. Once considered radical, A People’s History has gone mainstream. By 2002, Will Hunting had been replaced by A. J. Soprano of the HBO hit The Sopranos. Doing his homework at the kitchen counter, A. J. tells his parents that his history teacher compared Christopher Columbus to Slobodan Milošević. When Tony fumes, “Your teacher said that?” A. J. responds, “It’s not just my teacher—it’s the truth. It’s in my history book.” The camera pans to A. J. holding a copy of A People’s History.

With more than 2 million copies in print, Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United Statesis more than a book. It is a cultural icon. “You wanna read a real history book?” Matt Damon asks his therapist in the 1997 movie Good Will Hunting. “Read Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States. That book’ll … knock you on your ass.” The book’s original gray cover was painted red, white, and blue in 2003 and is now marketed with special displays in suburban megastores. Once considered radical, A People’s History has gone mainstream. By 2002, Will Hunting had been replaced by A. J. Soprano of the HBO hit The Sopranos. Doing his homework at the kitchen counter, A. J. tells his parents that his history teacher compared Christopher Columbus to Slobodan Milošević. When Tony fumes, “Your teacher said that?” A. J. responds, “It’s not just my teacher—it’s the truth. It’s in my history book.” The camera pans to A. J. holding a copy of A People’s History.

History, for Zinn, is looked at from “the bottom up”: a view “of the Constitution from the standpoint of the slaves, of Andrew Jackson as seen by the Cherokees, of the Civil War as seen by the New York Irish, of the Mexican war as seen by the deserting soldiers of Scott’s army.” Decades before we thought in such terms, Zinn provided a history for the 99 percent. Many teachers view A People’s History as an anti-textbook, a corrective to the narratives of progress dispensed by the state. This is undoubtedly true on a topical level.

More here.