Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

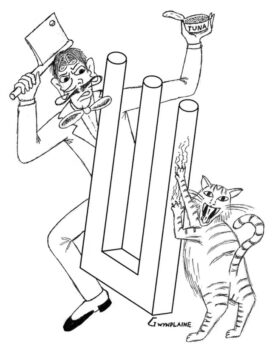

The Cat That Wouldnt Die

Jim Baggott at Aeon Magazine:

To understand the point Schrödinger was making, we need to do a little unpacking. The nature of Schrödinger’s ‘diabolical device’ is not actually important to his argument. Its purpose is simply to amplify an atomic-scale event – the decay of a radioactive atom – and bring it up to the more familiar scale of a living cat, trapped inside a steel box. The theory that describes objects and events taking place at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles like electrons is quantum mechanics. But in this theory, atoms and subatomic particles are described not as tiny, self-contained objects moving through space. They are instead described in terms of quantum wavefunctions, which capture an utterly weird aspect of their observed behaviour. Under certain circumstances, these particles may also behave like waves.

To understand the point Schrödinger was making, we need to do a little unpacking. The nature of Schrödinger’s ‘diabolical device’ is not actually important to his argument. Its purpose is simply to amplify an atomic-scale event – the decay of a radioactive atom – and bring it up to the more familiar scale of a living cat, trapped inside a steel box. The theory that describes objects and events taking place at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles like electrons is quantum mechanics. But in this theory, atoms and subatomic particles are described not as tiny, self-contained objects moving through space. They are instead described in terms of quantum wavefunctions, which capture an utterly weird aspect of their observed behaviour. Under certain circumstances, these particles may also behave like waves.

These contrasting behaviours could not be starker, or more seemingly incompatible. Particles have mass. By their nature, they are ‘here’: they are localised in space and remain localised as they move from here to there. Throw many particles into a small space and, like marbles, they will collide, bouncing off each other in different directions. Waves, on the other hand, are spread out through space – they are ‘non-local’. Squeeze them through a narrow slit and, like waves in the sea passing through a gap in a harbour wall, they will spread out beyond.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Richard Blanco turned from civil engineer to poet. Now he builds with words

Elizabeth Lund in The Christian Science Monitor:

Richard Blanco says he still can’t believe how much his life has changed since he read his poem “One Today” at U.S. President Barack Obama’s second inauguration in 2013. After his appearance, he received thousands of emails from people who appreciated his descriptions of hardworking Americans and immigrants, including his parents, and his vision of “All of us as vital as the one light we move through.”

Richard Blanco says he still can’t believe how much his life has changed since he read his poem “One Today” at U.S. President Barack Obama’s second inauguration in 2013. After his appearance, he received thousands of emails from people who appreciated his descriptions of hardworking Americans and immigrants, including his parents, and his vision of “All of us as vital as the one light we move through.”

“I could tell from their messages that [my reading] was probably the first time they had ever encountered a living poet writing in a voice and a language that they understood, feeling like they belonged to America,” says Mr. Blanco. “Some of them wouldn’t even dare to call it a poem. They were like, ‘We loved your speech.’”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

As AI’s power grows, charting its inner world is becoming more crucial

Edd Gent in Singularity Hub:

Older computer programs were hand-coded using logical rules. But neural networks learn skills on their own, and the way they represent what they’ve learned is notoriously difficult to parse, leading people to refer to the models as “black boxes.”

Older computer programs were hand-coded using logical rules. But neural networks learn skills on their own, and the way they represent what they’ve learned is notoriously difficult to parse, leading people to refer to the models as “black boxes.”

Progress is being made though, and Anthropic is leading the charge.

Last year, the company showed that it could link activity within a large language model to both concrete and abstract concepts. In a pair of new papers, it’s demonstrated that it can now trace how the models link these concepts together to drive decision-making and has used this technique to analyze how the model behaves on certain key tasks. “These findings aren’t just scientifically interesting—they represent significant progress towards our goal of understanding AI systems and making sure they’re reliable,” the researchers write in a blog post outlining the results. The Anthropic team carried out their research on the company’s Claude 3.5 Haiku model, its smallest offering. In the first paper, they trained a “replacement model” that mimics the way Haiku works but replaces internal features with ones that are more easily interpretable.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

I Am Mankind

I cry when I think what man

…………has done to man,

….Because I am the oppressed

…………and the oppressor.

I have caused deaths;

….I have died.

I have been tormentor;

….I have suffered.

I am mankind crying and laughing.

I have died in Hiroshima,

…………………………………. Dachowe,

………………………………………………. Arizona,

……………………………………………………………Mississippi,

I dropped the bomb on that little island.

I made lampshades from human skin,

I turned the snarling dogs on the Negro.

Naked, I cried at my mother’s side before the ovens.

Brazen, I laughed when I sentenced them to death.

Just as I am Sachi Yamuki,

………. I am Airman Frank Smith.

Just as I am Medgar Evers,

………. I am his white asssasin.

Just as I am Ann Frank,

………. I am Adolph Eichmann.

Just as I am Running Deer,

………. I am Senator Ratner (R. Ariz.)

My being depends upon the heterogeneous group of

………. Men ;

Yet I insist on destroying myself.

I kill my Asians,

………………………………Jews,

………………………………………. Indians,

…………………………………………………… Blacks,

……………………………………………………………… Myself.

I am the puzzling paradox of the universe and time.

I am the Schizophrenic, Mankind.

I ask, when will I lose my evil self?

Tell me, will I abolish the evil in me?

Answer me please, before I destroy myself.

by Kathleen McGrath

from Essence Magazine

Paterson State College Press, 1963

…I have died.

…………

…………

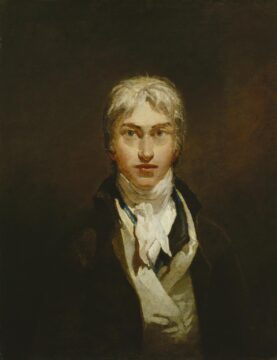

The Second Birth of JMW Turner

Michael Prodger at The New Statesman:

JMW Turner baffled his contemporaries. At the beginning of his career he was a prodigy, a preternaturally gifted tyro who joined the Royal Academy Schools at 14, and at 15 became the youngest painter ever to have a picture accepted for the RA Summer Exhibition. But at the end of his career his peers found his paintings incomprehensible. All those wafty emanations of light, colour and atmospherics had no precedent and no explanation. John Ruskin thought his late work displayed “distinctive characters in the execution, indicative of mental disease”. A fellow painter, Benjamin Robert Haydon, thought that “Turner’s pictures always look as if painted by a man who was born without hands” who had “contrived to tie a brush to the hook at the end of his wooden stump.” One critic was inspired by Turner’s ochre depictions of the ruins of Rome to brush off his Latin: the paintings, he said, were “cacatum non est pictum” – crapped not painted.

The man himself was equally mystifying. For the last five years of his life he had been living with a woman named Sophia Booth, a twice-widowed guesthouse landlady 20 years his junior.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, May 6, 2025

To resist dogma and accept uncertainty, think like a pragmatist

Michael Bacon at Psyche:

In the everyday sense of the term, the pragmatist is the person who ‘gets results’. The term can be intended as either a compliment or a criticism; it can be applied equally to effective and to unscrupulous managers and politicians. These connotations carry over, typically in misleading ways, into the philosophical sense of pragmatism.

In the everyday sense of the term, the pragmatist is the person who ‘gets results’. The term can be intended as either a compliment or a criticism; it can be applied equally to effective and to unscrupulous managers and politicians. These connotations carry over, typically in misleading ways, into the philosophical sense of pragmatism.

Pragmatism is the United States’ most important contribution to philosophy, emerging in the late 19th century, developing throughout the 20th, and flourishing today. At its heart is a rejection of what one of its founders, John Dewey (1859-1952), calls ‘the spectator theory of knowledge’. This theory, which can be traced to Plato, holds that reality is composed of two discrete entities: the world of objects, which exist independently of us, and the minds, which perceive and seek accurately to represent that world. In the alternative account offered by pragmatists, the mind is, rather, a part of the world, in which it plays an active role. Pragmatists, accordingly, describe us not as seeking to represent reality as it exists independently of us, but rather as developing more effective and imaginative ways of coping with the circumstances in which we find ourselves.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Review of “Is a River Alive?” by Robert Macfarlane

Blake Morrison in The Guardian:

Tracking a river through a cedar forest in Ecuador, Robert Macfarlane comes to a 30ft-high waterfall and, below it, a wide pool. It’s irresistible: he plunges in. The water under the falls is turbulent, a thousand little fists punching his shoulders. He’s exhilarated. No one could mistake this for a “dying” river, sluggish or polluted. But that thought sparks others: “Is this thing I’m in really alive? By whose standards? By what proof? As for speaking to or for a river, or comprehending what a river wants – well, where would you even start?”

Tracking a river through a cedar forest in Ecuador, Robert Macfarlane comes to a 30ft-high waterfall and, below it, a wide pool. It’s irresistible: he plunges in. The water under the falls is turbulent, a thousand little fists punching his shoulders. He’s exhilarated. No one could mistake this for a “dying” river, sluggish or polluted. But that thought sparks others: “Is this thing I’m in really alive? By whose standards? By what proof? As for speaking to or for a river, or comprehending what a river wants – well, where would you even start?”

He’s in the right place to be asking. In September 2008, Ecuador, “this small country with a vast moral imagination”, became the first nation in the world to legislate on behalf of water, “since its condition as an essential element for life makes it a necessary aspect for existence of all living beings”. This enshrinement of the Rights of Nature set off similar developments in other countries. In 2017, a law was passed in New Zealand that afforded the Whanganui River protection as a “spiritual and physical entity”. In India, five days later, judges ruled that the Ganges and Yamuna should be recognised as “living entities”. And in 2021, the Mutehekau Shipu (AKA Magpie River) became the first river in Canada to be declared a “legal person [and] living entity”. The Rights of Nature movement has now reached the UK, with Lewes council in East Sussex recognising the rights and legal personhood of the River Ouse.

Macfarlane’s book is timely. Rivers are in crisis worldwide. They have been dammed, poisoned, reduced to servitude, erased from the map.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Consciousness, Reasoning and the Philosophy of AI with Murray Shanahan

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tensions over Kashmir and a warming planet have placed the Indus Waters Treaty on life support

Fazlul Haq in The Conversation:

In 1995, World Bank Vice President Ismail Serageldin warned that whereas the conflicts of the previous 100 years had been over oil, “the wars of the next century will be fought over water.”

In 1995, World Bank Vice President Ismail Serageldin warned that whereas the conflicts of the previous 100 years had been over oil, “the wars of the next century will be fought over water.”

Thirty years on, that prediction is being tested in one of the world’s most volatile regions: Kashmir.

On April 24, 2025, the government of India announced that it would downgrade diplomatic ties with its neighbor Pakistan over an attack by militants in Kashmir that killed 26 tourists. As part of that cooling of relations, India said it would immediately suspend the Indus Waters Treaty – a decades-old agreement that allowed both countries to share water use from the rivers that flow from India into Pakistan. Pakistan has promised reciprocal moves and warned that any disruption to its water supply would be considered “an act of war.”

The current flareup escalated quickly, but has a long history.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Marguerite Porete: Heretic or Martyr

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

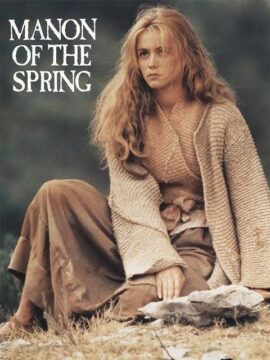

Jean de Florette and Manon of the Spring

Sue Harris at The Current:

When Jean de Florette, the first part of Claude Berri’s magisterial two-film adaptation of Marcel Pagnol’s celebrated 1962 literary diptych, L’eau des collines, was released in theaters in August 1986—the second part, Manon of the Spring, would follow in November—it was the cinematic event of the year in France. The films ran during an exceptionally tough time for the French, who were on constant alert as they went about their daily lives because of a terrorist bombing campaign that had been targeting Paris and regional transportation networks since December 1985. One can only imagine what a relief it must have been to escape to a cinema for a few hours and be transported to 1920s rural France and a world imagined by one of the country’s most beloved and prolific chroniclers of Provençal life. Shot simultaneously on location in rural Provence over the last half of 1985, the two parts drew many millions of domestic spectators, capturing the top two box-office spots for 1986.

When Jean de Florette, the first part of Claude Berri’s magisterial two-film adaptation of Marcel Pagnol’s celebrated 1962 literary diptych, L’eau des collines, was released in theaters in August 1986—the second part, Manon of the Spring, would follow in November—it was the cinematic event of the year in France. The films ran during an exceptionally tough time for the French, who were on constant alert as they went about their daily lives because of a terrorist bombing campaign that had been targeting Paris and regional transportation networks since December 1985. One can only imagine what a relief it must have been to escape to a cinema for a few hours and be transported to 1920s rural France and a world imagined by one of the country’s most beloved and prolific chroniclers of Provençal life. Shot simultaneously on location in rural Provence over the last half of 1985, the two parts drew many millions of domestic spectators, capturing the top two box-office spots for 1986.

Jean de Florette and Manon of the Spring present Provence as a feast for the senses, a spectacular landscape of trees and mountains, dirt tracks and sun-bleached stone cottages. Our eyes, like those of Jean Cadoret, the first part’s protagonist, roam freely over the hills and valleys, soaring and sweeping, drinking in both the immensity of the land and its permanence.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

S. Abbas Raza interviews Richard Dawkins

Note: I have heard this interview many times over the years. Every time, it strikes me as startlingly fresh and relevant for the time. Even Professor Dawkins admitted that the questions Abbas asked were some of the best he had ever been asked and that he greatly enjoyed the interview himself.

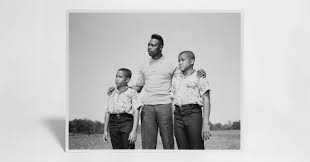

The Surprising Ways That Siblings Shape Our Lives

Susan Dominus in The New York Times:

When we think about the forces that shape us, we inevitably turn to parents. The parent-child relationship is the basis of probably half a millennium’s worth of psychoanalytic conversation and intellectual discourse; parenting books are perennial best sellers, with advice that fluctuates as often as the health advice on what to eat or drink and how much. Their whiplashing instructions don’t stop many parents from reading them, and who can blame those mothers and fathers: Children are baffling, variable, not that verbal — and parents also know that if they get it wrong, their kids will blame them for just about everything.

When we think about the forces that shape us, we inevitably turn to parents. The parent-child relationship is the basis of probably half a millennium’s worth of psychoanalytic conversation and intellectual discourse; parenting books are perennial best sellers, with advice that fluctuates as often as the health advice on what to eat or drink and how much. Their whiplashing instructions don’t stop many parents from reading them, and who can blame those mothers and fathers: Children are baffling, variable, not that verbal — and parents also know that if they get it wrong, their kids will blame them for just about everything.

And yet researchers, after analyzing thousands of twin studies, have come to the conclusion that the shared environment — the environment that siblings have in common, which includes parents — seems to do precious little to make fraternal twins particularly alike in many ways. They can be exposed to the same rules of oboe practice, dinnertime rituals, punishments, family values and parental harmony or discord, and none of it really matters in many key regards — siblings’ personalities may very well end up as different as those of any two strangers on the street. No one would argue that parenting doesn’t matter; it’s just that the choices so many loving parents agonize over — whether to co-sleep or not, whether to enforce the rules rigidly or sometimes let them go — don’t matter nearly as much as we imagine they do. Nor does that mean that genes are all-powerful; it’s just that nurture comprises so much more than parenting — the environmental effects a child is exposed to are vast, and include (just to start) the media they consume and the friends and teachers in whose company they spend most of the day.

And then there are siblings.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

The Great Circle of Nothing

When I AM THAT I AM made nothing

and rested, which rest it certainly deserved,

night now accompanied day, and man

had his friend in the absence of the woman.

Let there be shadow! Human thinking broke out.

And the universal egg rose, empty,

pale, chill and not yet heavy with matter,

full of un weighable mist, in his hand.

Take the numerical zero, the sphere with nothing in it:

it has to be seen, if you have to see it, standing.

Since the wild animal’s back is now your shoulder,

and since the miracle of not-being is finished,

start then, poet, a song at the edge of it all

to death, to silence, and to what does not return.

by Antonio Machado

from Times Alone

Wesleyan University Press, 1983

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

What Can We Learn from Broken Things?

Josh Rothman at The New Yorker:

There are philosophies of brokenness, which makes sense, given how much broken stuff disrupts the flow of our lives. How should we think about those disruptions? A practitioner of the Japanese ethic of wabi-sabi respects the beauty of brokenness: instead of trying to erase the wear and tear that accrues inevitably with time, she finds ways of acknowledging and celebrating it. In a prototypical example of the philosophy, a teacup that has fallen and shattered is reassembled through the art of kintsugi, in which lacquer, mixed with powdered gold or other metals, is used to fill the cracks; now the fractured, gilded cup tells a story of endurance, authenticity, acceptance, and care amid impermanence. Your favorite jacket, with a mended tear in its lining and the mark of an exploded pen below its pocket, has some wabi-sabi. So does your grandfather’s watch, still functional but with a scratch in its crystal. I like to imagine that the Wabi Sabi Salon, in a town near mine, helps its clients age gracefully. (I’ve never visited.)

There are philosophies of brokenness, which makes sense, given how much broken stuff disrupts the flow of our lives. How should we think about those disruptions? A practitioner of the Japanese ethic of wabi-sabi respects the beauty of brokenness: instead of trying to erase the wear and tear that accrues inevitably with time, she finds ways of acknowledging and celebrating it. In a prototypical example of the philosophy, a teacup that has fallen and shattered is reassembled through the art of kintsugi, in which lacquer, mixed with powdered gold or other metals, is used to fill the cracks; now the fractured, gilded cup tells a story of endurance, authenticity, acceptance, and care amid impermanence. Your favorite jacket, with a mended tear in its lining and the mark of an exploded pen below its pocket, has some wabi-sabi. So does your grandfather’s watch, still functional but with a scratch in its crystal. I like to imagine that the Wabi Sabi Salon, in a town near mine, helps its clients age gracefully. (I’ve never visited.)

The German philosopher Martin Heidegger, who wrote about how we experience ourselves and the world, argued that there were two ways we could relate to objects. A doorknob, he thought, could be “ready-to-hand”—something we reach for and use reflexively, unconsciously, without a moment’s thought. But that same doorknob, if it breaks, can become “present-at-hand”: precisely because it’s not working, we notice it, examine it, try to figure it out so we can fix it. Broken things are often “there” for us in ways that working things aren’t.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, May 5, 2025

BBC harnesses AI to create writing classes given by Agatha Christie

Lucy Knight in The Guardian:

The videos “starring” the author, who died in 1976, have been made using AI-enhanced technology, licensed images and carefully restored audio recordings.

The videos “starring” the author, who died in 1976, have been made using AI-enhanced technology, licensed images and carefully restored audio recordings.

Videos made using a reconstruction of Christie’s voice will share tips on everything from story structure and plot twists to the art of suspense.

The writing advice has been drawn directly from her writings and archival interviews and curated by the leading Christie scholars Dr Mark Aldridge, Michelle Kazmer, Gray Robert Brown and Jamie Bernthal-Hooker.

“We meticulously pieced together Agatha Christie’s own words from her letters, interviews and writings,” Aldridge said. “Witnessing her insights come to life has been a profoundly moving experience.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Human Evolution Traded Fur for Sweat Glands—and Now, Our Wounds Take Longer to Heal Than Those of Other Mammals

Sarah Kuta in Smithsonian Magazine:

The follicles at the root of each hair contain stem cells, which, in addition to producing hair, can grow new skin when necessary. Since humans have much less hair than other mammals do, it makes sense that our wounds would also take longer to heal.

The follicles at the root of each hair contain stem cells, which, in addition to producing hair, can grow new skin when necessary. Since humans have much less hair than other mammals do, it makes sense that our wounds would also take longer to heal.

“When the epidermis is wounded, as in most kinds of scratches and scrapes, it’s really the hair-follicle stem cells that do the repair,” says Elaine Fuchs, a biologist at Rockefeller University who was not involved with the research, to the New York Times’ Elizabeth Preston.

At some point in the evolutionary journey, humans lost most of their body hair. Since chimps’ wounds heal faster than ours, this shift likely occurred after humans diverged from our shared ancestor with the primates, reports New Scientist’s Chris Simms.

It’s not entirely clear why early humans lost their hair. But it seems our species swapped the once-abundant hair follicles for sweat glands, which are not as efficient at healing wounds but help keep us cool in hot environments.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

K2-18b and the Search for Life: Exciting Discovery or a False Alarm?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

50 years later, Vietnam’s environment still bears the scars of war – and signals a dark future for Gaza and Ukraine

Pamela McElwee in The Conversation:

When the Vietnam War finally ended on April 30, 1975, it left behind a landscape scarred with environmental damage. Vast stretches of coastal mangroves, once housing rich stocks of fish and birds, lay in ruins. Forests that had boasted hundreds of species were reduced to dried-out fragments, overgrown with invasive grasses.

When the Vietnam War finally ended on April 30, 1975, it left behind a landscape scarred with environmental damage. Vast stretches of coastal mangroves, once housing rich stocks of fish and birds, lay in ruins. Forests that had boasted hundreds of species were reduced to dried-out fragments, overgrown with invasive grasses.

The term “ecocide” had been coined in the late 1960s to describe the U.S. military’s use of herbicides like Agent Orange and incendiary weapons like napalm to battle guerrilla forces that used jungles and marshes for cover.

Fifty years later, Vietnam’s degraded ecosystems and dioxin-contaminated soils and waters still reflect the long-term ecological consequences of the war. Efforts to restore these damaged landscapes and even to assess the long-term harm have been limited.

As an environmental scientist and anthropologist who has worked in Vietnam since the 1990s, I find the neglect and slow recovery efforts deeply troubling. Although the war spurred new international treaties aimed at protecting the environment during wartime, these efforts failed to compel post-war restoration for Vietnam. Current conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East show these laws and treaties still aren’t effective.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.