Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Listening to the Nonhuman World

Jonathan S. Blake at the LARB:

Bringing nonhumans into our democracies may be less radical than it first appears. Nussbaum is quick to clarify that attending to the political voices of animals does not mean giving them a vote in our elections, which “would quickly become absurd.” Her vision is not of beleaguered pets marching down our grand boulevards demanding the vote for every Sparky, Buddy, and Princess. Rather more modestly, she proposes that “duly qualified animal ‘collaborators’ should be charged with making policy on the animals’ behalf, and bringing challenges to unjust arrangements in the courts.” The goal is not to force animals with “little interest in political participation in the human-dominated world” to suddenly take part in “elections, assemblies, and offices.” Nussbaum’s ambition, rather, is for expert guardians to give the “creatures who live in a place […] a say in how they live.”

Bringing nonhumans into our democracies may be less radical than it first appears. Nussbaum is quick to clarify that attending to the political voices of animals does not mean giving them a vote in our elections, which “would quickly become absurd.” Her vision is not of beleaguered pets marching down our grand boulevards demanding the vote for every Sparky, Buddy, and Princess. Rather more modestly, she proposes that “duly qualified animal ‘collaborators’ should be charged with making policy on the animals’ behalf, and bringing challenges to unjust arrangements in the courts.” The goal is not to force animals with “little interest in political participation in the human-dominated world” to suddenly take part in “elections, assemblies, and offices.” Nussbaum’s ambition, rather, is for expert guardians to give the “creatures who live in a place […] a say in how they live.”

The “creatures” at the heart of her account are individual, often named animals—Virginia the elephant, Lupa the dog. “[T]his is a book about loss and deprivation suffered by individual creatures, each of whom matters,” Nussbaum states. “Species as such do not suffer loss.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

‘Marriage feels like a hostage situation, and motherhood a curse’: Japanese author Sayaka Murata

Lisa Allardice in The Guardian:

From a very young age, Murata never thought of her body as her own. “The grownups would always talk about whether Sayaka had childbearing hips,” she recalls. “It was almost like they were keeping an eye on my uterus, which was something that existed not for me, but for them, for the relatives.” No matter how much she tried to resolve the conflict of motherhood in her fiction, she has never escaped “this idea of being expected to reproduce for the good of the village”.

From a very young age, Murata never thought of her body as her own. “The grownups would always talk about whether Sayaka had childbearing hips,” she recalls. “It was almost like they were keeping an eye on my uterus, which was something that existed not for me, but for them, for the relatives.” No matter how much she tried to resolve the conflict of motherhood in her fiction, she has never escaped “this idea of being expected to reproduce for the good of the village”.

She found erotic magazines hidden in her older brother’s bedroom. “It was all over the place,” she says of the culture at that time; even the manga comics aimed at young girls involved the characters being forced to take their clothes off. “So I didn’t think of sexual love as something that I could choose for myself,” she says. “I always thought of my body as a tool for men to relieve their sexual desires.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Keith McNally’s Rearview Mirror

Rosa Shipley at The Paris Review:

“Restaurants will break your heart” is something that I often hear myself saying. It has become a mantra. When did I start saying it, I wonder. Maybe it was when I first discovered the criss-crossed lines of affection; falling in a crash-out kind of love with a fellow line cook because he helped me with my mise en place. Maybe it was when my sous-chef first called me mediocre; we all watched slices of chocolate cake I cut pile up in the garbage because of my disappointing quenelles. Maybe it was the first time that I had to fire a kitchen assistant over the phone, hearing him quietly murmur in response, “Okay.” Maybe (definitely) it was the time I got fired—the bad news sandwiched between my manager saying I was “amazing” and also “so great.” Maybe it was the first time I watched a plate of food I made go out and I understood, profoundly, that I would never know who might eat it.

“Restaurants will break your heart” is something that I often hear myself saying. It has become a mantra. When did I start saying it, I wonder. Maybe it was when I first discovered the criss-crossed lines of affection; falling in a crash-out kind of love with a fellow line cook because he helped me with my mise en place. Maybe it was when my sous-chef first called me mediocre; we all watched slices of chocolate cake I cut pile up in the garbage because of my disappointing quenelles. Maybe it was the first time that I had to fire a kitchen assistant over the phone, hearing him quietly murmur in response, “Okay.” Maybe (definitely) it was the time I got fired—the bad news sandwiched between my manager saying I was “amazing” and also “so great.” Maybe it was the first time I watched a plate of food I made go out and I understood, profoundly, that I would never know who might eat it.

In his new memoir, I Regret Almost Everything, Keith McNally’s tells us that his heart has been broken many times over—but it seems that restaurants are, in fact, what have saved him. As a diner, his restaurants have certainly given me much life force and heart-mend; they are perhaps the most accessibly glamorous in New York City, where I grew up.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

five of the most impactful science stories from the past week

Taking my lead from Abbas, I asked ChatGpt to help. This is what it said:

1. ESA’s Euclid Telescope Unveils Millions of New Galaxies

1. ESA’s Euclid Telescope Unveils Millions of New Galaxies

The European Space Agency’s Euclid mission released its first major data set, revealing millions of previously unseen galaxies. This “treasure trove” offers new insights into dark matter and the large-scale structure of the universe, marking a significant step forward in cosmology .Smithsonian Magazine

2. CAR-T Therapy Shows 18-Year Cancer Remission

A patient treated with CAR-T cell therapy for neuroblastoma remains cancer-free 18 years later. This long-term success suggests that CAR-T, previously effective mainly for blood cancers, may also be a viable treatment for solid tumors .Science News

3. SpaceX Sets Rocket Reuse Record

SpaceX achieved a new milestone by launching the same Falcon 9 rocket twice within nine days, breaking its previous turnaround record. This rapid reuse capability could significantly reduce the cost and increase the frequency of space missions .UPI

4. Advancements in Insect Imaging Using Synchrotron Technology

Researchers at the Diamond Light Source synchrotron in the UK are employing high-resolution X-ray technology to study insect anatomy in unprecedented detail. This approach is enhancing our understanding of insect evolution and biodiversity, crucial as insect populations face significant declines .Financial Times

5. Private Mission to Venus Aims to Detect Signs of Life

A private space mission, named Morning Star, is set to explore Venus’s atmosphere for potential signs of life. If successful, it would be the first private mission to another planet and could provide valuable data on the planet’s habitability .Science News+1UPI+1

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, May 4, 2025

Andy Bey (1939 – 2025) Jazz Singer and Pianist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

David Horowitz (1939 – 2025) Political Writer and Activist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Mike Peters (1959 – 2025) Musician

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A user-friendly opera about Steve Jobs powers up at the Kennedy Center

Michael Brodeur in The Washington Post:

“The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs” doesn’t so much begin as start up. When the first flourish of composer Mason  Bates’s score rings out — a wobbly, synthetic chime of sorts — you’d swear someone had pressed a power button in the orchestra pit. On Friday evening at the Kennedy Center, the Washington National Opera opened its production of Bates’s opera with a libretto by Mark Campbell — its tenth since the opera’s premiere at Santa Fe Opera in 2017. Guest conductor Lidiya Yankovskaya led the Washington National Opera Orchestra and Chorus in this revival of Tomer Zvulun’s production, here directed by Rebecca Herman.

Bates’s score rings out — a wobbly, synthetic chime of sorts — you’d swear someone had pressed a power button in the orchestra pit. On Friday evening at the Kennedy Center, the Washington National Opera opened its production of Bates’s opera with a libretto by Mark Campbell — its tenth since the opera’s premiere at Santa Fe Opera in 2017. Guest conductor Lidiya Yankovskaya led the Washington National Opera Orchestra and Chorus in this revival of Tomer Zvulun’s production, here directed by Rebecca Herman.

The set is an austere arrangement of scaffolding and screens, a versatile scheme that shuttles viewers through time and space: from the humble garage workshop where Jobs and Steve Wozniak first tinkered with their clunky prototypes in the early 1970s, to the depths of Yosemite National Park in the early 1990s, to a tech conference in San Francisco where the iPhone was launched in 2007 — though not necessarily in that order.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

(Don’t Be Squeamish) The Unlikely Cure for a Gut Disease

Gabriel Weston in Undark Magazine:

The most immutable fact they teach you in medical school is that anatomy is the absolute bedrock of surgery. As an eager young surgical intern, I often got doused in my patients’ vomit and shit. I tried to see the clinical bright side: Maybe the old man’s feces contained blood or the teen who had barfed up the offending Tylenol would avoid a liver transplant. Otherwise, the contents of normal guts were of less interest.

The most immutable fact they teach you in medical school is that anatomy is the absolute bedrock of surgery. As an eager young surgical intern, I often got doused in my patients’ vomit and shit. I tried to see the clinical bright side: Maybe the old man’s feces contained blood or the teen who had barfed up the offending Tylenol would avoid a liver transplant. Otherwise, the contents of normal guts were of less interest.

Back then, we were taught that the sole purpose of the gastrointestinal tract was to extract nutrients from food. What I didn’t expect, after practicing as a surgeon myself for over 20 years, is that what we think we know about human anatomy is actually changing all the time and that our bodies are more varied, more full of wonders and magical revelations, than we could ever have imagined.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On the Brink?

Tariq Ali in Sidecar:

India and Pakistan are preparing for war. The casus belli is, once again, occupied Kashmir. Control over this disputed region has since 1947 been the main obstacle to normalising relations between the two states. On 21 April, a group of Kashmiri militants targeted and killed 26 tourists enjoying the beauty of Pahalgam’s flower-filled meadows, crystal streams and snow-capped mountains; responsibility for the attack was claimed and then quickly disavowed by a little-known organization called the ‘Resistance Front’. This was a particular affront to Narendra Modi (whose record includes presiding, as Chief Minister, over the slaughter of an estimated 2,000 civilians in the 2002 Gujarat massacre, and long a defender of anti-Muslim pogroms). A far-right Hindu nationalist now in his third term as India’s Prime Minister, Modi had previously declared that there was no longer any serious Kashmir problem. His final solution – revoking Kashmir’s autonomous status in 2019 – had succeeded.

Nothing justifies the slaughter of the Pahalgam holidaymakers, and vanishingly few Kashmiri or Indian Muslims would support actions of this sort. But historical context is necessary to understand the overall situation in the province. Even Israel has a Ha’aretz. Not India. Kashmir remains an untouchable subject. This Muslim-majority province has never been allowed to determine its own fate, as promised by Congress leaders at the time of Independence. Instead, it was partitioned between the new republics of India and Pakistan after a short war in which the British commander of the Pakistan Army refused to agree to its use, leaving a ragtag force to face off against India’s regular troops. That well-known pacifist, Mahatma Gandhi, blessed the Indian invasion. Articles 370 and 35A of the Indian Constitution were supposed to guarantee Kashmir’s special status, not least by forbidding non-Kashmiris the right to buy property and settle there. This was combined with brutal repression of any stirrings of discontent, turning Kashmir into a police state with military units never too far away.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Intellectual Historians Confront the Present

Leonard Benardo interviews Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins over at The Ideas Letter:

Leonard Benardo: I thought I would begin by asking you why you think the field of Intellectual History has made such an unanticipated resurgence in recent years. At some point, only a decade or so ago, it was seemingly on the brink of turning moribund, and if you were interested in the area you would have been well advised to go to law school instead. Jobs were scarce. What happened? What were the triggers that reignited the field? How do you account for the turn in terms of structure, ideology, and otherwise?

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins: I do think intellectual history has been revitalized but primarily outside the confines of the academy. Of course, there are plenty of great intellectual historians currently writing, but the field has experienced the same fate as the general history profession in terms of the so-called academic jobs crisis that has significantly deepened since 2016. Even if one was to be admitted to Harvard, Yale, or Princeton to study intellectual history, it is probably unlikely that doing so would lead to a tenure-track job. I think there is a hesitancy for professors at even these places to take on students as they know there is a good chance it will not result in a tenure-track offer. Whenever one of my students at Wesleyan says they want to go to grad school to become a history professor, I feel an ethical obligation to explain to them the risk involved in that decision. In terms of your comment about law school, I encourage them to do a PhD/JD so that if a history job doesn’t materialize, they at least have the fallback option of a law career or even becoming a law professor. Of course, some students are privileged enough so as not to have to worry about the risk, which means that we might end up with a profession, in a generation, dominated by a particular class.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Brian Eno’s Theory of Democracy

Henry Farrell over at his substack Programmable Mutter:

The back story to this post doesn’t start with Brian Eno. Back in 1991, the political scientist Adam Przeworski published a book, Democracy and the Market. Most of the book was about the democratic transition in Central and Eastern Europe, and it was very good as best as I can judge these things. But the first chapter was much, much better than very good. It laid out a brief theory of democracy that reshaped the ways in which political scientists think about it.

Przeworski’s theory starts from a simple seeming claim: that “democracy is a system in which parties lose elections.” It then uses a combination of game theory and informal argument to lay out the implications. If we assume (as Przeworski assumes) that parties and political decision makers are self-centered, why would the ruling party ever accept that they had lost and relinquish control of government? Przeworski argues that it must somehow be in their self-interest to so. He argues that they will admit defeat if they see that the alternative is worse, and (this is crucial) because democracy generates sufficient uncertainty about the future that they believe they might win in some future election. They know that they will hurt their interests if they refuse to give in, and they have some (unquantifiable but real) prospect of coming back into power again. Democracy, then, will be stable so long as the expectation of costs and the uncertainty of the future give the losers sufficient incentive to accept that they have lost.

This is a more beautiful idea than I am able to explain in a brief post, and certainly much more beautiful than any argument I will ever come up with myself. It compresses a vast and turbid system of enmeshed ambitions and behaviors into a deceptively simple nine word thesis

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

Me he perdido muchas veces por el mar

I I’ve lost myself many times in the sea

Ghazal for Lorca

Had Lorca been in India, he would have been lost in the sea of courtesans

Not the coquetry of Andalusian women, but dusky moaning courtesans

Had Lorca been in Lahore for versos, he would have visited the Lahore Fort,

the duende and Dionysian blood wedding of a yearning courtesan

Had Lorca met me in the surreal setting across the Taj Mahal, we would

have penned Rubaiyat, an assembly of tears, simmering courtesans!

Had Lorca searched for jasmine and vendors around the Royal Mosque

I would have preferred to sleep and supplicate with a courtesan,

Had Lorca instead of Basilica, chosen the shrine of a saint in Lahore,

the Genile, grooved by tobaccos, a puff of love with my courtesan,

Had I been there where Lora was martyred, I would have grieved long

till churches had stopped tolling; better die embracing a courtesan,

Had Lorca and Agha Shahid encountered and roamed for Rekhta in Kashmir,

Rizwan would have breached borders, exporting ghazals with courtesans.

by Prof.Dr. Rizwan Akhtar

Institute of English Studies

Punjab University

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, May 2, 2025

Testing AI’s GeoGuessr Genius

Scott Alexander at Astral Codex Ten:

Last week, Kelsey Piper claimed that o3 – OpenAI’s latest ChatGPT model – could achieve seemingly impossible feats in GeoGuessr. She gave it this picture:

…and with no further questions, it determined the exact location (Marina State Beach, Monterey, CA).

How? She linked a transcript where o3 tried to explain its reasoning, but the explanation isn’t very good. It said things like:

Tan sand, medium surf, sparse foredune, U.S.-style kite motif, frequent overcast in winter … Sand hue and grain size match many California state-park beaches. California’s winter marine layer often produces exactly this thick, even gray sky.

Commenters suggested that it was lying. Maybe there was hidden metadata in the image, or o3 remembered where Kelsey lived from previous conversations, or it traced her IP, or it cheated some other way.

I decided to test the limits of this phenomenon.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

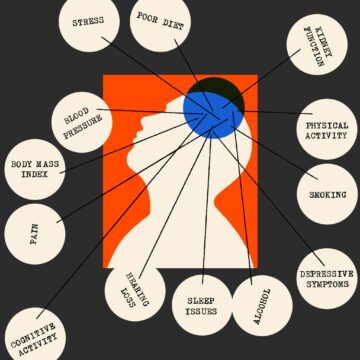

Ways to Cut Your Risk of Stroke, Dementia and Depression All at Once

Nina Agrawal in the New York Times:

New research has identified 17 overlapping factors that affect your risk of stroke, dementia and late-life depression, suggesting that a number of lifestyle changes could simultaneously lower the risk of all three.

New research has identified 17 overlapping factors that affect your risk of stroke, dementia and late-life depression, suggesting that a number of lifestyle changes could simultaneously lower the risk of all three.

Though they may appear unrelated, people who have dementia or depression or who experience a stroke also often end up having one or both of the other conditions, said Dr. Sanjula Singh, a principal investigator at the Brain Care Labs at Massachusetts General Hospital and the lead author of the study. That’s because they may share underlying damage to small blood vessels in the brain, experts said.

Some of the risk factors common to the three brain diseases, including high blood pressure and diabetes, appear to cause this kind of damage. Research suggests that at least 60 percent of strokes, 40 percent of dementia cases and 35 percent of late-life depression cases could be prevented or slowed by controlling risk factors.

“Those are striking numbers,” said Dr. Stephanie Collier, director of education in the division of geriatric psychiatry at McLean Hospital in Massachusetts. “If you can really optimize the lifestyle pieces or the modifiable pieces, then you’re at such a higher likelihood of living life without disability.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

“Godfather of AI” Geoffrey Hinton shares predictions for future of AI

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Robert Crumb and Dan Nadel with Naomi Fry

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A Modern Counterrevolution

Bernard E. Harcourt in The Ideas Letter:

In a blizzard of executive orders and emergency declarations, President Donald Trump has taken a hatchet to the American government and the global order. He is wrecking the administrative state, shuttering entire agencies and departments, laying off federal workers, firing inspectors general. He is deporting permanent residents for speech protected by the First Amendment, revoking visas from international students, sending immigrants to the military camp at Guantánamo Bay and a mega-prison in El Salvador, and trying to eliminate birthright citizenship. He is defunding research universities and attacking the legal profession. He is threatening draconian tariffs on the country’s closest allies and neighbors, demeaning their leaders, and pulling the United States out of longstanding international commitments. Every day, he launches another unprecedented offensive or changes course; he creates ambiguity and fuels confusion, leaving his critics to second-guess themselves while giving himself cover.

He remains extremely popular with his base, even if his overall ratings have dropped to record lows. His critics, though, attack him six ways from Sunday. They call him a fascist, an authoritarian, a tyrant, the kleptocratic tool of tech billionaires, a profiteer, a reality-TV impostor, the embodiment of toxic masculinity, a bully. Yet none of these labels fully captures the scope or the coherence of what is happening in the U.S. today. These diagnoses focus too much on the individual, and this is an individual who, like a virtuoso illusionist, keeps his audience mesmerized by the spectacle but distracted from what is really going on. The radical developments underway must be placed in deeper perspective.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Working at Krispy Kreme

Kate Durbin at The Baffler:

My favorite thing to do at Krispy Kreme to stave off the boredom is stack the donuts on top of each other and then squish them down into a “sandwich.” When they are hot, they flatten in an extreme way. I can get about twelve in the pile before things get messy. Some days, this donut sandwich is all I eat, other than maybe one other thing, a giant slice of pizza from Sbarro or orange chicken from Panda Express in the mall across the vast parking lot, which I pay for with my meager tip money. I also drink excessive amounts of the whole chocolate milk we sell. This anorexic, sugary diet means I weigh just under 110 pounds and am always jittery.

My favorite thing to do at Krispy Kreme to stave off the boredom is stack the donuts on top of each other and then squish them down into a “sandwich.” When they are hot, they flatten in an extreme way. I can get about twelve in the pile before things get messy. Some days, this donut sandwich is all I eat, other than maybe one other thing, a giant slice of pizza from Sbarro or orange chicken from Panda Express in the mall across the vast parking lot, which I pay for with my meager tip money. I also drink excessive amounts of the whole chocolate milk we sell. This anorexic, sugary diet means I weigh just under 110 pounds and am always jittery.

I get home at night bone-exhausted. Peel my shoes from my swollen feet, dirty white Vans I got at Journeys in the mall, skater shoes that reek of sweat but also sweetness. The donut smell baked into the shoe’s material. Years later it will still be there when I finally throw those shoes away.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.