Bennett McIntosh in Harvard Magazine:

Before ancient humans put pen to paper, stylus to tablet, or even brush to cave wall, their comings and goings were noted in another record, within their very cells. The human genome consists of chunks of DNA passed forward from countless ancestors, so by comparing modern humans’ genetic material with that gleaned from ancient remains, it’s possible to reach into prehistory and learn about where people came from, and who they were. David Reich, professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, has spent the last decade extracting these stories from ancient DNA, using genetic evidence to overturn established theories and conventional wisdom about humanity’s past. But, so far, at least, the DNA has provided little clarity on the more fundamental question of our origin—what makes us human in the first place? In yesterday’s Distinguished Harvard Lecture in Mind Brain Behavior, Reich highlighted the transformative power—and tantalizing limitations—of ancient DNA in reshaping understanding of how Homo sapiens came to be and to act like modern humans.

Before ancient humans put pen to paper, stylus to tablet, or even brush to cave wall, their comings and goings were noted in another record, within their very cells. The human genome consists of chunks of DNA passed forward from countless ancestors, so by comparing modern humans’ genetic material with that gleaned from ancient remains, it’s possible to reach into prehistory and learn about where people came from, and who they were. David Reich, professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, has spent the last decade extracting these stories from ancient DNA, using genetic evidence to overturn established theories and conventional wisdom about humanity’s past. But, so far, at least, the DNA has provided little clarity on the more fundamental question of our origin—what makes us human in the first place? In yesterday’s Distinguished Harvard Lecture in Mind Brain Behavior, Reich highlighted the transformative power—and tantalizing limitations—of ancient DNA in reshaping understanding of how Homo sapiens came to be and to act like modern humans.

The Mind Brain Behavior (MBB) interfaculty initiative, which celebrated its twenty-fifth birthday earlier this year, is one of several initiatives at Harvard that provide funding and programming for collaboration across the University’s different schools, with the aim of bringing researchers together to better understand an interdisciplinary research topic—in this case, the biology driving human behavior. The biannual Distinguished Harvard Lectures give students and researchers involved in the initiative a venue to hear about research in other fields that directly impacts their own. The room was packed with faculty members from different schools and departments, a reflection of the profound influence Reich’s research has had on many fields studying human behavior.

More here.

Men of action present a problem for decent modern democrats. For the very term “men of action” is a euphemism for men accomplished in war, and no public figure is more suspect these days than the warlike man. When Winston Churchill called Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) “the greatest man of action born in Europe since Julius Caesar,” he meant to praise Napoleon in the highest terms, but for many, such praise is fraught with peril. After all, Julius Caesar, named dictator in perpetuity, placed the Roman Republic in mortal danger and died a tyrant’s death; the most famous of his assassins, Marcus Junius Brutus, is remembered as a paragon of republican virtue, though it proved impossible to restore the Republic after Caesar’s day.

Men of action present a problem for decent modern democrats. For the very term “men of action” is a euphemism for men accomplished in war, and no public figure is more suspect these days than the warlike man. When Winston Churchill called Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) “the greatest man of action born in Europe since Julius Caesar,” he meant to praise Napoleon in the highest terms, but for many, such praise is fraught with peril. After all, Julius Caesar, named dictator in perpetuity, placed the Roman Republic in mortal danger and died a tyrant’s death; the most famous of his assassins, Marcus Junius Brutus, is remembered as a paragon of republican virtue, though it proved impossible to restore the Republic after Caesar’s day. Paul Krugman, blogger, fiat-currency enthusiast and winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics earlier this year justified his scepticism about cryptocurrencies in the New York Times. He asked readers to give him a clear answer to the question: what is the problem cryptocurrency solves? He wrote: ‘Governments have occasionally abused the privilege of creating fiat money, but for the most part governments and central banks exercise restraint.’ He added that, unlike bitcoin, ‘fiat currencies have underlying value because men with guns say they do. And this means that their value isn’t a bubble that can collapse if people lose faith.’

Paul Krugman, blogger, fiat-currency enthusiast and winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics earlier this year justified his scepticism about cryptocurrencies in the New York Times. He asked readers to give him a clear answer to the question: what is the problem cryptocurrency solves? He wrote: ‘Governments have occasionally abused the privilege of creating fiat money, but for the most part governments and central banks exercise restraint.’ He added that, unlike bitcoin, ‘fiat currencies have underlying value because men with guns say they do. And this means that their value isn’t a bubble that can collapse if people lose faith.’ It’s a huge day for archaeologists and anyone interested in the history of America’s first settlers. Findings from three new genetics studies—all released today—are presenting a fascinating, yet complex, picture of the first people in North and South America, and how they spread and diversified across two continents.

It’s a huge day for archaeologists and anyone interested in the history of America’s first settlers. Findings from three new genetics studies—all released today—are presenting a fascinating, yet complex, picture of the first people in North and South America, and how they spread and diversified across two continents. It’s fun to be in the exciting, chaotic, youthful days of the podcast, when anything goes and experimentation is the order of the day. So today’s show is something different: a solo effort, featuring just me talking without any guests to cramp my style. This won’t be the usual format, but I suspect it will happen from time to time. Feel free to chime in below on how often you think alternative formats should be part of the mix.

It’s fun to be in the exciting, chaotic, youthful days of the podcast, when anything goes and experimentation is the order of the day. So today’s show is something different: a solo effort, featuring just me talking without any guests to cramp my style. This won’t be the usual format, but I suspect it will happen from time to time. Feel free to chime in below on how often you think alternative formats should be part of the mix.

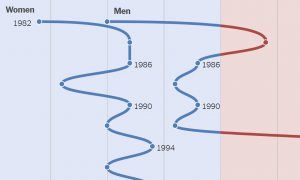

In the 2016 presidential election, 55 percent of white women voted for Republicans. And this year, the group backed Democrats and Republicans evenly.

In the 2016 presidential election, 55 percent of white women voted for Republicans. And this year, the group backed Democrats and Republicans evenly.

The fascination of what’s difficult,” wrote WB Yeats, “has dried the sap out of my veins … ” In the press coverage of this year’s Man Booker prize winner, Anna Burns’s

The fascination of what’s difficult,” wrote WB Yeats, “has dried the sap out of my veins … ” In the press coverage of this year’s Man Booker prize winner, Anna Burns’s  The futurist philosopher Yuval Noah Harari worries about a lot. He worries that Silicon Valley is undermining democracy and ushering in a dystopian hellscape in which voting is obsolete. He worries that by creating powerful influence machines to control billions of minds, the big tech companies are destroying the idea of a sovereign individual with free will. He worries that because the technological revolution’s work requires so few laborers, Silicon Valley is creating a tiny ruling class and a teeming, furious “useless class.” But lately, Mr. Harari is anxious about something much more personal. If this is his harrowing warning, then why do Silicon Valley C.E.O.s love him so? “One possibility is that my message is not threatening to them, and so they embrace it?” a puzzled Mr. Harari said one afternoon in October. “For me, that’s more worrying. Maybe I’m missing something?”

The futurist philosopher Yuval Noah Harari worries about a lot. He worries that Silicon Valley is undermining democracy and ushering in a dystopian hellscape in which voting is obsolete. He worries that by creating powerful influence machines to control billions of minds, the big tech companies are destroying the idea of a sovereign individual with free will. He worries that because the technological revolution’s work requires so few laborers, Silicon Valley is creating a tiny ruling class and a teeming, furious “useless class.” But lately, Mr. Harari is anxious about something much more personal. If this is his harrowing warning, then why do Silicon Valley C.E.O.s love him so? “One possibility is that my message is not threatening to them, and so they embrace it?” a puzzled Mr. Harari said one afternoon in October. “For me, that’s more worrying. Maybe I’m missing something?” Following the sensational success of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, with no less than 2.5 million copies of the book sold worldwide, inequality is now widely perceived, to quote Bernie Sanders, as “the great moral issue of our time.” Clearly the shift is part of a wider transformation of American and European politics in the wake the 2008 crash that has turned the “1%” into an object of increasing attention. Marx’s Capital is now a bestseller in the “

Following the sensational success of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, with no less than 2.5 million copies of the book sold worldwide, inequality is now widely perceived, to quote Bernie Sanders, as “the great moral issue of our time.” Clearly the shift is part of a wider transformation of American and European politics in the wake the 2008 crash that has turned the “1%” into an object of increasing attention. Marx’s Capital is now a bestseller in the “

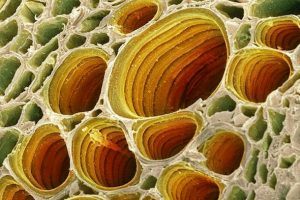

Because biology is the result of evolution and not human development, bringing engineering principles to it is guaranteed to fail. Or so goes the argument behind the “Grove fallacy,”

Because biology is the result of evolution and not human development, bringing engineering principles to it is guaranteed to fail. Or so goes the argument behind the “Grove fallacy,”  Growing up, I never considered myself to be particularly nice, perhaps because I’m from a rural part of New Brunswick, one of Canada’s Maritime Provinces—the conspicuously “nicest” region in a self-consciously nice country. My parents are nice in a way that almost beggars belief—my mother’s tact is such that the strongest condemnation in her arsenal is “Well, I wouldn’t say I don’t like it, per se…” As for me, teenage eye-rolls gave way to undergraduate seriousness, which gave way to graduate-student irony. I thought of Atlantic Canadian nice as a convenient way to avoid telling the truth about the way things are—a disingenuous evasion of the nasty truth about the world. Even the word nice seems the moral equivalent of “uninteresting”—anodyne, tedious, otiose.

Growing up, I never considered myself to be particularly nice, perhaps because I’m from a rural part of New Brunswick, one of Canada’s Maritime Provinces—the conspicuously “nicest” region in a self-consciously nice country. My parents are nice in a way that almost beggars belief—my mother’s tact is such that the strongest condemnation in her arsenal is “Well, I wouldn’t say I don’t like it, per se…” As for me, teenage eye-rolls gave way to undergraduate seriousness, which gave way to graduate-student irony. I thought of Atlantic Canadian nice as a convenient way to avoid telling the truth about the way things are—a disingenuous evasion of the nasty truth about the world. Even the word nice seems the moral equivalent of “uninteresting”—anodyne, tedious, otiose.