Category: Recommended Reading

Wah Wah Watson (1950 – 2018)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wneQYox0jWo

Sonny Fortune (1939 – 2018)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dB1PH9mLswA

Blue Wave: 29-year-old Mexican-Palestinian-American Ammar Campa-Najjar is shaking up California

Sophie McBain in New Statesman America:

When Ammar Campa-Najjar was nine years old, his Palestinian father moved his family to Gaza, the narrow strip of Palestinian territory that has been under an Israeli blockade for over a decade. His family was living there when the second intifada broke out in 2000, and Israeli security forces crushed a violent Palestinian uprising with deadly and often indiscriminate force. He remembers when the electricity and water supply were cut off and sheltering in his kitchen while his neighbourhood was bombed. He remembers how a military Hummer crashed into his family’s car, causing him to burn his back and fracture his thigh and putting his younger brother into a coma.

When Ammar Campa-Najjar was nine years old, his Palestinian father moved his family to Gaza, the narrow strip of Palestinian territory that has been under an Israeli blockade for over a decade. His family was living there when the second intifada broke out in 2000, and Israeli security forces crushed a violent Palestinian uprising with deadly and often indiscriminate force. He remembers when the electricity and water supply were cut off and sheltering in his kitchen while his neighbourhood was bombed. He remembers how a military Hummer crashed into his family’s car, causing him to burn his back and fracture his thigh and putting his younger brother into a coma.

“It was a pretty formative experience. I saw the deep economic injustice that was happening and certain conditions that are better left imagined than described. But then you see them happening here, in America too, the wealthiest and most powerful country,” Campa-Najjar tells me when we speak on the phone. “I thought to myself when I came back to America… why am I seeing similar conditions in the US?”

Campa-Najjar, a 29-year-old former Obama staffer whose boyband good looks have inspired Buzzfeed and Vogue articles, as well as much Twitter mirth, is running for Congress is California’s 50th district on a progressive agenda. Like many of the candidates New Statesman America is profiling ahead of the midterms, he has been endorsed by the Congressional Progressive Caucus, a group that is likely to emerge as a leading force should the Democrats flip Congress this year. Its members support policies such as Medicare-for-all, an increased minimum wage and an expansion of social security. The Californian 50th district has been held by Republican Duncan Hunter for over a decade, and before that it was held by his father. Donald Trump won the district by 15 points in 2016. But Campa-Najjar’s chances were boosted significantly in August when Hunter was indicted for using more than $250,000 of campaign funds for personal expenses. Campa-Najjar has also launched a powerful grassroots campaign and has the endorsement of his former boss, President Barack Obama. Recent polling has put Campa-Najjar within one or two points of Hunter in the midterms.

More here.

Saturday, November 3, 2018

Jeffrey D. Sachs on Killer Politicians

Jeffrey D. Sachs in Project Syndicate:

“Will no one rid me of this meddlesome priest?” asked Henry II as he instigated the murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, in 1170. Down through the ages, presidents and princes around the world have been murderers and accessories to murder, as the great Harvard sociologist Pitirim Sorokin and Walter Lunden documented in statistical detail in their masterwork Power and Morality. One of their main findings was that the behavior of ruling groups tends to be more criminal and amoral than that of the people over whom they rule.

“Will no one rid me of this meddlesome priest?” asked Henry II as he instigated the murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, in 1170. Down through the ages, presidents and princes around the world have been murderers and accessories to murder, as the great Harvard sociologist Pitirim Sorokin and Walter Lunden documented in statistical detail in their masterwork Power and Morality. One of their main findings was that the behavior of ruling groups tends to be more criminal and amoral than that of the people over whom they rule.

What rulers crave most is deniability. But with the murder of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi by his own government, the poisoning of former Russian spies living in the United Kingdom, and whispers that the head of Interpol, Meng Hongwei, may have been executed in China, the curtain has been slipping more than usual of late. In Riyadh, Moscow, and even Beijing, the political class is scrambling to cover up its lethal ways.

But no one should feel self-righteous here. American presidents have a long history of murder, something unlikely to trouble the current incumbent, Donald Trump, whose favorite predecessor, Andrew Jackson, was a cold-blooded murderer, slaveowner, and ethnic cleanser of native Americans. For Harry Truman, the atomic bombing of Hiroshima spared him the likely high cost of invading Japan. But the second atomic bombing, of Nagasaki, was utterly indefensible and took place through sheer bureaucratic momentum: the bombing apparently occurred without Truman’s explicit order.

More here.

What Is Real? The Unfinished Quest for the Meaning of Quantum Physics

Sheldon Lee Glashow in Inference Review:

IN THE ANNUS MIRABILIS of 1905, Albert Einstein made several seminal contributions to science. Among them were the special theory of relativity and the recognition of the wave-particle duality of light—the latter a characteristic of the quantum theory soon to emerge. Modern physics rests on quantum mechanics and relativity. Both revert to classical physics under everyday circumstances: quantum mechanics for things sufficiently large; special relativity for things sufficiently slow. Within their domains, both theories have consequences that seem crazy, counterintuitive, and contrary to experience. For decades I have striven to convey the delights of modern physics to science-averse undergraduates, but many of them persist in rejecting the concepts as either unacceptable or unbelievable.

IN THE ANNUS MIRABILIS of 1905, Albert Einstein made several seminal contributions to science. Among them were the special theory of relativity and the recognition of the wave-particle duality of light—the latter a characteristic of the quantum theory soon to emerge. Modern physics rests on quantum mechanics and relativity. Both revert to classical physics under everyday circumstances: quantum mechanics for things sufficiently large; special relativity for things sufficiently slow. Within their domains, both theories have consequences that seem crazy, counterintuitive, and contrary to experience. For decades I have striven to convey the delights of modern physics to science-averse undergraduates, but many of them persist in rejecting the concepts as either unacceptable or unbelievable.

Antoine Lavoisier and James Prescott Joule were wrong! Relativity revealed energy and mass to be interconvertible, satisfying a single, unified conservation law. Who could believe that simultaneity is relative, or that no missile nor missive can travel faster than light? A clock in motion, said Einstein, ticks more slowly than an identical clock at rest. Relativistic time dilation is ordinarily negligible, except to science fiction writers, philosophers, and physicists who study rapidly moving particles.

What Is Real? is a book focusing on the counterintuitive nature of quantum theory, the difficulties in its interpretation, and the various doomed attempts to introduce hidden variables into its structure. I found it distasteful to find a trained astrophysicist invoking a conspiracy by physicists and physics teachers to foist the Copenhagen interpretation upon naive students of quantum mechanics.

More here.

Mainstream Macroeconomics and Modern Monetary Theory: What Really Divides Them?

Arjun Jayadev and J. W. Mason in the Institute for New Economic Thinking:

An increasingly visible school of heterodox macroeconomics, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), makes the case for functional finance—the view that governments should set their fiscal position at whatever level is consistent with price stability and full employment, regardless of current debt or deficits. Functional finance is widely understood, by both supporters and opponents, as a departure from orthodox macroeconomics. We argue that this perception is mistaken: While MMT’s policy proposals are unorthodox, the analysis underlying them is entirely orthodox. A central bank able to control domestic interest rates is a sufficient condition to allow a government to freely pursue countercyclical fiscal policy with no danger of a runaway increase in the debt ratio. The difference between MMT and orthodox policy can be thought of as a different assignment of the two instruments of fiscal position and interest rate to the two targets of price stability and debt stability. As such, the debate between them hinges not on any fundamental difference of analysis, but rather on different practical judgements—in particular what kinds of errors are most likely from policymakers.

An increasingly visible school of heterodox macroeconomics, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), makes the case for functional finance—the view that governments should set their fiscal position at whatever level is consistent with price stability and full employment, regardless of current debt or deficits. Functional finance is widely understood, by both supporters and opponents, as a departure from orthodox macroeconomics. We argue that this perception is mistaken: While MMT’s policy proposals are unorthodox, the analysis underlying them is entirely orthodox. A central bank able to control domestic interest rates is a sufficient condition to allow a government to freely pursue countercyclical fiscal policy with no danger of a runaway increase in the debt ratio. The difference between MMT and orthodox policy can be thought of as a different assignment of the two instruments of fiscal position and interest rate to the two targets of price stability and debt stability. As such, the debate between them hinges not on any fundamental difference of analysis, but rather on different practical judgements—in particular what kinds of errors are most likely from policymakers.

Anyone who has followed debates on macroeconomic policy in recent years will be familiar with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

More here.

La Carpinese – L’Arpeggiata

American Perceptions of Class

Matt Wray at Public Books:

So, again, why is there no socialism in the United States? Perhaps when the millennial generation comes to power, the question will no longer make much sense. But if these enthusiastic young fans of socialist democracy are ever to win big in American electoral politics, it’s going to be because they will have figured out a new way to talk about class in America. And to do that, they will need to understand some of the different ways that Americans have thought—and felt—about class. And to do that, they might want to read a neglected classic of American sociology—The American Perception of Class, by Reeve Vanneman and Lynn Cannon, just reissued as an open access title by Temple University Press and available for free download here.1 The book is a classic example of how to use sociological reasoning and methods to debunk widely held myths. In this case, the myths were about the lack of class consciousness in America, myths that can be traced back to Sombart.

So, again, why is there no socialism in the United States? Perhaps when the millennial generation comes to power, the question will no longer make much sense. But if these enthusiastic young fans of socialist democracy are ever to win big in American electoral politics, it’s going to be because they will have figured out a new way to talk about class in America. And to do that, they will need to understand some of the different ways that Americans have thought—and felt—about class. And to do that, they might want to read a neglected classic of American sociology—The American Perception of Class, by Reeve Vanneman and Lynn Cannon, just reissued as an open access title by Temple University Press and available for free download here.1 The book is a classic example of how to use sociological reasoning and methods to debunk widely held myths. In this case, the myths were about the lack of class consciousness in America, myths that can be traced back to Sombart.

more here.

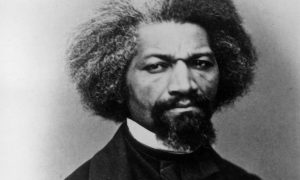

Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

John S. Gardner at The Guardian:

“Douglass engaged in a lifelong autobiographical quest for a coherent story of ascendance and familial identity,” Blight writes, and “for the healing of his own wounds”. Douglass himself thundered that slavery “converted the mother that bore me into a myth, it shrouded my father in mystery, and left me without an intelligible beginning in the world”. He yearned for “a bright gleam of a mother’s love”.

“Douglass engaged in a lifelong autobiographical quest for a coherent story of ascendance and familial identity,” Blight writes, and “for the healing of his own wounds”. Douglass himself thundered that slavery “converted the mother that bore me into a myth, it shrouded my father in mystery, and left me without an intelligible beginning in the world”. He yearned for “a bright gleam of a mother’s love”.

This is a monumental book, a definitive biography, rich with the biblical cadences that filled Douglass’ life and imagination. Slavery, redemption, vengeance, justice: these were Douglass’ themes, and like Jeremiah he would be a prophet to an often recalcitrant people. The lecture halls expected no less yet Douglass gave them more, probing new depths of social and political analysis, constantly imploring greater exertion for the causes of emancipation and full equality, unafraid to make his hearers deeply uncomfortable.

more here.

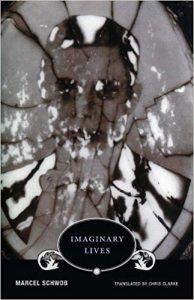

‘Imaginary Lives’ by Marcel Schwob

Alex Andriesse at The Quarterly Conversation:

Imaginary Lives (1896) was Schwob’s last book of fiction. He composed its twenty-two chapters—each one the story of a life, recounted in fewer than a dozen pages, with all of these lives arranged in chronological order—between 1893 and 1896. Early in its composition, at the age of twenty-six, Schwob suffered the first attack of a mysterious intestinal ailment whose painful effects and questionable treatments (ether, opium, morphine) would lead to his death at thirty-seven. Schwob’s physical condition to some extent shaped his fiction, and though all the chapters of Imaginary Lives culminate, naturally enough, in their subjects’ deaths, these deaths are often unnaturally violent. Lucretius the Poet is poisoned by his lover. Clodia the Licentious Matron is strangled, robbed, and dumped in the river Tiber. Gabriel Spenser the Actor is stabbed in the lung by Ben Jonson the playwright. And the three pirates of the book (Captain Kidd, Walter Kennedy, Stede Bonnet) are hanged and left to rot upon the rope. Imaginary Lives is, among other things, a study of human violence, proceeding from the sun-stroked era of ancient Greek gods and demigods to the soot-blackened nineteenth-century Edinburgh of the serial murderers Burke and Hare.

Imaginary Lives (1896) was Schwob’s last book of fiction. He composed its twenty-two chapters—each one the story of a life, recounted in fewer than a dozen pages, with all of these lives arranged in chronological order—between 1893 and 1896. Early in its composition, at the age of twenty-six, Schwob suffered the first attack of a mysterious intestinal ailment whose painful effects and questionable treatments (ether, opium, morphine) would lead to his death at thirty-seven. Schwob’s physical condition to some extent shaped his fiction, and though all the chapters of Imaginary Lives culminate, naturally enough, in their subjects’ deaths, these deaths are often unnaturally violent. Lucretius the Poet is poisoned by his lover. Clodia the Licentious Matron is strangled, robbed, and dumped in the river Tiber. Gabriel Spenser the Actor is stabbed in the lung by Ben Jonson the playwright. And the three pirates of the book (Captain Kidd, Walter Kennedy, Stede Bonnet) are hanged and left to rot upon the rope. Imaginary Lives is, among other things, a study of human violence, proceeding from the sun-stroked era of ancient Greek gods and demigods to the soot-blackened nineteenth-century Edinburgh of the serial murderers Burke and Hare.

more here.

‘Friday Black’ Paints a Dark Portrait of Race in America

Tommy Orange in The New York Times:

This year has been exhausting in so many ways, asking us to accept more than it seems we can, more than it seems should be possible. But really, in the end, today’s harsh realities are not all that surprising for some of us — for people of color, or for people from marginalized communities — who have long since given up on being shocked or dismayed by the news, by what this or that administration will allow, what this or that police department will excuse, who will be exonerated, what this or that fellow American is willing to let be, either by contribution or complicity. All this is done in the name of white supremacy under the guise of patriotism and conservatism, to keep things as they are, favoring white people over every other citizen, because where’s the incentive to give up privilege if you have it? Now more than ever I believe fiction can change minds, build empathy by asking readers to walk in others’ shoes, and thereby contribute to real change. In “Friday Black,” Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah has written a powerful and important and strange and beautiful collection of stories meant to be read right now, at the end of this year, as we inch ever closer to what feels like an inevitable phenomenal catastrophe or some other kind of radical change, for better or for worse. And when you can’t believe what’s happening in reality, there is no better time to suspend your disbelief and read and trust in a work of fiction — in what it can do.

This year has been exhausting in so many ways, asking us to accept more than it seems we can, more than it seems should be possible. But really, in the end, today’s harsh realities are not all that surprising for some of us — for people of color, or for people from marginalized communities — who have long since given up on being shocked or dismayed by the news, by what this or that administration will allow, what this or that police department will excuse, who will be exonerated, what this or that fellow American is willing to let be, either by contribution or complicity. All this is done in the name of white supremacy under the guise of patriotism and conservatism, to keep things as they are, favoring white people over every other citizen, because where’s the incentive to give up privilege if you have it? Now more than ever I believe fiction can change minds, build empathy by asking readers to walk in others’ shoes, and thereby contribute to real change. In “Friday Black,” Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah has written a powerful and important and strange and beautiful collection of stories meant to be read right now, at the end of this year, as we inch ever closer to what feels like an inevitable phenomenal catastrophe or some other kind of radical change, for better or for worse. And when you can’t believe what’s happening in reality, there is no better time to suspend your disbelief and read and trust in a work of fiction — in what it can do.

Adjei-Brenyah grew up in a suburb of New York and graduated with his M.F.A. from Syracuse University, where he was taught by the short story master George Saunders. “Friday Black” is an unbelievable debut, one that announces a new and necessary American voice. This is a dystopian story collection as full of violence as it is of heart. To achieve such an honest pairing of gore with tenderness is no small feat. The two stories that bookend the collection are the most gruesome, and maybe my favorites. Where they could be seen as gratuitous (at least to those readers who are not paying close attention to the news, or to those who intentionally avert their eyes), I find them perfectly paced narratives filled with crackling dialogue and a rewarding balance of tension and release. Violence is only gratuitous when it serves no purpose, and throughout “Friday Black” we are aware that the violence is crucially related to both what is happening in America now, and what happened in its bloody and brutal history.

More here.

Noam Chomsky Argues the ‘Revival of Hate’ Fueled by Trump’s Rhetoric Extends Back to Ronald Reagan

Cody Fenwick in AlterNet:

Linguist and long-time political gadfly Noam Chomsky argued in an interview Friday that President Donald Trump’s poisonous and violent rhetoric fueling hatred in the United States has a deep lineage in the country — and also accentuates the country’s role in an “alliance of reactionary and repressive states” worldwide. Asked by Democracy Now’s Amy Goodman to reflect on the recent anti-Semitic massacre in Pittsburgh at which 11 Jewish people were killed by a gunman, Chomsky, who was born in Philadelphia, noted that the hatred reflected what he saw in his youth — though it is less severe now. “When I was a child, the threat that fascism might take over much of the world was not remote,” he said. “That’s much worse than what we’re facing now. My own locality happened to be very anti-Semitic.” He continued: “What we’re now seeing is a revival of hate, anger, fear, much of it encouraged by the rhetorical excesses of the leadership, which are stirring up passions and terror, even the ludicrous claims about the Nicaraguan army ready to invade us—Ronald Reagan—the caravan of miserable people ‘planning to kill us all.’ All of these things, plus, you know, praising somebody who body-slammed a reporter, one thing after another — all of this raises the level of anger and fear, which has roots.”

Linguist and long-time political gadfly Noam Chomsky argued in an interview Friday that President Donald Trump’s poisonous and violent rhetoric fueling hatred in the United States has a deep lineage in the country — and also accentuates the country’s role in an “alliance of reactionary and repressive states” worldwide. Asked by Democracy Now’s Amy Goodman to reflect on the recent anti-Semitic massacre in Pittsburgh at which 11 Jewish people were killed by a gunman, Chomsky, who was born in Philadelphia, noted that the hatred reflected what he saw in his youth — though it is less severe now. “When I was a child, the threat that fascism might take over much of the world was not remote,” he said. “That’s much worse than what we’re facing now. My own locality happened to be very anti-Semitic.” He continued: “What we’re now seeing is a revival of hate, anger, fear, much of it encouraged by the rhetorical excesses of the leadership, which are stirring up passions and terror, even the ludicrous claims about the Nicaraguan army ready to invade us—Ronald Reagan—the caravan of miserable people ‘planning to kill us all.’ All of these things, plus, you know, praising somebody who body-slammed a reporter, one thing after another — all of this raises the level of anger and fear, which has roots.”

The roots of this distress, he argued, dates back 40 years in the United States as the American government has abandoned any role in supporting workers and families. In response to the fact that Israel has defended the president and argued that there’s anti-Semitism on both sides of the political spectrum, Chomsky was unsurprised. Israel, too, had been engaged in its own campaign of suppression and fearmongering of the Palestinians, and it finds an ideological partner in a far-right United States.

More here.

Friday, November 2, 2018

Is Sex Binary? The answer offered in a recent New York Times opinion piece is more confusing than enlightening

Alex Byrne in Arc Digital:

In her New York Times op-ed “Why Sex Is Not Binary,” the biologist and gender studies theorist Anne Fausto-Sterling tries to set the record straight: “Two sexes have never been enough to describe human variety.” According to Fausto-Sterling, it has “long been known” that some people are neither female nor male (or, perhaps, both female and male).

In her New York Times op-ed “Why Sex Is Not Binary,” the biologist and gender studies theorist Anne Fausto-Sterling tries to set the record straight: “Two sexes have never been enough to describe human variety.” According to Fausto-Sterling, it has “long been known” that some people are neither female nor male (or, perhaps, both female and male).

Fausto-Sterling is responding to a leaked draft memo from the Department of Health and Human Services that proposes a legal definition of sex under Title IX “based on immutable biological traits.” The memo appears to be part of a regrettable attempt to remove some legal protections from people who are transgender. Although a transgender person is no less likely to be female or male than someone who is not transgender, activists for transgender rights often cite the alleged fact that “sex is not binary” to support the idea that being transgender is not a mental health condition, but instead is merely “normal biological variation.” That “sex is a spectrum,” or — as Fausto-Sterling wrote in The New York Times 25 years ago — that “there are at least five sexes,” are claims that are pressed into similar service. Fausto-Sterling’s article endorses and reinforces these ideas. But not only are the claimed biological facts far from established, this particular use of biology to guide social and legal issues is completely misguided in the first place. Transgender people, just like anyone else, should be free to live and work without being stigmatized, harassed, or disrespected. Whether sex is binary, a spectrum, or whether there are 42 sexes, makes absolutely no difference.

More here.

Wait, Have We Really Wiped Out 60 Percent of Animals?

Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

Since Monday, news networks and social media have been abuzz with the claim that, as The Guardian among others tweeted, “humanity has wiped out 60 percent of animals since 1970”—a stark and staggering figure based on the latest iteration of the WWF’s Living Planet report.

But that isn’t really what the report showed.

The team behind the Living Planet Index relied on previous studies in which researchers estimated the size of different animal populations, whether through direct counts, camera traps, satellites, or proxies like the presence of nests or tracks. The team collated such estimates for 16,700 populations of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish, across 4,000 species. (Populations here refers to pockets of individuals from a given species that live in distinct geographical areas.)

That covers just 6.4 percent of the 63,000 or so species of vertebrates—that is, back-boned animals—that are thought to exist. To work out how the entire group has fared, the team adjusted its figures to account for any biases in its data. For example, vertebrates in Europe have been more heavily studied than those in South America, and prominently endangered creatures like elephants have been more closely studied (and have been easier to count) than very common ones like pigeons.

More here.

Pakistan’s Hybrid Government and the Aasia Bibi Fiasco

Omar Ali in Brown Pundits:

Aasia bibi is a poor Christian woman from a village in Punjab who was arrested for blasphemy in 2009. She got into an argument with some other women from the village while working in the fields (purportedly over her drinking from a cup of water and hence “polluting” it) and in the course of the argument she allegedly said something “blasphemous” about the holy prophet of Islam. The details of the case are murky and no one seems to know for sure what blasphemous statement she actually made that day (the most commonly reported one is that she said something along the lines of “Jesus died for the sins of the world, what has your prophet done for humanity”; other versions exist; the investigating police officer claims that she said much more, but even quoting it wud be blasphemy, so look it up on wikipedia) but whatever the details, a case was registered under Pakistan’s uniquely harsh blasphemy law (a death sentence is mandatory in case guilt is proven) and she has been in prison ever since.

Aasia bibi is a poor Christian woman from a village in Punjab who was arrested for blasphemy in 2009. She got into an argument with some other women from the village while working in the fields (purportedly over her drinking from a cup of water and hence “polluting” it) and in the course of the argument she allegedly said something “blasphemous” about the holy prophet of Islam. The details of the case are murky and no one seems to know for sure what blasphemous statement she actually made that day (the most commonly reported one is that she said something along the lines of “Jesus died for the sins of the world, what has your prophet done for humanity”; other versions exist; the investigating police officer claims that she said much more, but even quoting it wud be blasphemy, so look it up on wikipedia) but whatever the details, a case was registered under Pakistan’s uniquely harsh blasphemy law (a death sentence is mandatory in case guilt is proven) and she has been in prison ever since.

As usually happens in blasphemy cases, she was sentenced to death by the local court (local judges usually feel it safest to convict any and all accused blasphemers, expecting that the most egregiously wrong verdicts will be reversed by higher courts that have better security). Meanwhile her case had come to national attention and the governor of Punjab, Salman Taseer, visited her in prison and spoke of her getting a presidential pardon. He was attacked in the media as a supporter of blasphemers and one of his own body guards shot him dead. The body guard was arrested and eventually hanged, but his grave has become a religious shrine and several ministers (including some in the current Imran Khan government as well as the opposition PMLN) have visited the grave to pay respects to this “hero”.

More here.

What if He Falls?

Aase Berg’s Poetry of Horror and Kitsch

Logan Berry and Kathleen Rooney at Poetry Magazine:

In his 1927 essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” the influential horror writer H.P. Lovecraft declares that “the oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is the fear of the unknown.” The contemporary Swedish poet Aase Berg invites readers to not resist the unknown but to dwell, and even revel, in it. Johannes Göransson, who has translated four of Berg’s collections into English, writes that her work “has been deeply influenced by horror: horror movies, b-movies, and H.P. Lovecraft (whose work she’s been translating for years). All of these influences can be seen in the violent, grotesque, intense imagery and ecriture-feminine-like linguistic deformation zones of her first two books.” Indeed, reading Berg can feel like the literary equivalent of the fairy tale dare to spend the night in a haunted house: threatening but giddy at the same time.

In his 1927 essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” the influential horror writer H.P. Lovecraft declares that “the oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is the fear of the unknown.” The contemporary Swedish poet Aase Berg invites readers to not resist the unknown but to dwell, and even revel, in it. Johannes Göransson, who has translated four of Berg’s collections into English, writes that her work “has been deeply influenced by horror: horror movies, b-movies, and H.P. Lovecraft (whose work she’s been translating for years). All of these influences can be seen in the violent, grotesque, intense imagery and ecriture-feminine-like linguistic deformation zones of her first two books.” Indeed, reading Berg can feel like the literary equivalent of the fairy tale dare to spend the night in a haunted house: threatening but giddy at the same time.

Born in Stockholm in 1967 and raised in the suburb of Tensta, Berg was a founding member of the Stockholm Surrealist Group, established in 1986, in which loosely affiliated writers produced literary journals through the late 1990s.

more here.

Left-wing Climate Realism

Ajay Singh Chaudhary at n+1:

IN AN ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STUDY that made headlines last month, the Trump Administration argued that anthropogenic climate change is likely to lead to a 4°C increase in average temperatures by 2100. According to the memo, modest reforms, like the fuel-efficiency standards the study was aiming to overturn, will make no appreciable difference in global climate change.

That outrage greeted the release of this memo was unsurprising. Throughout his candidacy and his presidency, Trump has preferred to think of climate change as a “Chinese hoax,” and his administration, like all recent Republican regimes, has committed itself to an accelerated anti-environmentalism, overturning with ecstatic vigor its predecessor’s modest restraints and regulations. Still, in its own perverse way, the Trump study is one of the most forthright presentations on climate change to come from a Global North government in recent memory.

more here.

On Reading Knausgaard

Fredric Jameson at the LRB:

I will add, however, that whatever bother he has caused his family and his friends, he has also made trouble for his reviewers, who cannot deal with this the way they deal with an ordinary book (whether it is a famous masterpiece or a worthless paperback). Actually, the truly most frequently asked question is: do I have to read this, is it any good? A question to which there may or may not be a satisfactory answer, but which can at least be smothered by the information that people do seem to be reading it and that it has been translated into more than thirty languages around the world and has sold hundreds of thousands of copies and become a literary sensation, on the order of Roberto Bolaño or Elena Ferrante (both also somewhat autobiographical, it should be added). So the more satisfactory response would be to take a poll (preferably worldwide) and find out what its readers think. I believe the result would be that they cannot tell you whether they think it is good or not either, but also that they all agree it exercises a certain fascination that keeps you reading. This fascination is what a proper reviewer would have to analyse. Otherwise, you are reduced to the status of the art teacher, moving from pupil to pupil and saying, this part is really good, there is something wrong with the anatomy of this figure, there’s something missing in the lower left part of the picture, that part has an interesting colour combination, etc. I’m afraid I will have to do that too, since I agreed to review this book.

I will add, however, that whatever bother he has caused his family and his friends, he has also made trouble for his reviewers, who cannot deal with this the way they deal with an ordinary book (whether it is a famous masterpiece or a worthless paperback). Actually, the truly most frequently asked question is: do I have to read this, is it any good? A question to which there may or may not be a satisfactory answer, but which can at least be smothered by the information that people do seem to be reading it and that it has been translated into more than thirty languages around the world and has sold hundreds of thousands of copies and become a literary sensation, on the order of Roberto Bolaño or Elena Ferrante (both also somewhat autobiographical, it should be added). So the more satisfactory response would be to take a poll (preferably worldwide) and find out what its readers think. I believe the result would be that they cannot tell you whether they think it is good or not either, but also that they all agree it exercises a certain fascination that keeps you reading. This fascination is what a proper reviewer would have to analyse. Otherwise, you are reduced to the status of the art teacher, moving from pupil to pupil and saying, this part is really good, there is something wrong with the anatomy of this figure, there’s something missing in the lower left part of the picture, that part has an interesting colour combination, etc. I’m afraid I will have to do that too, since I agreed to review this book.

more here.