Category: Recommended Reading

Why Do We Love Joni Mitchell the Way We Do?

Nick Coleman at Literary Hub:

Mitchell settled in the imaginations of pop listeners in the early 70s. In the UK, “Big Yellow Taxi” was a biggish hit in the summer of 1970, its glassily sardonic reflections upon humanity’s relationship with the environment marking out the flaxen-haired Scando-Canadian hippie-chick who sang it as a poster girl for a certain kind of wholesome big-R Romanticism. She was fey, frowning, Nordically bony, the perfect package for the deal: a one-take archetype. What the songs didn’t articulate and the voice didn’t swoop upon like a slender bird, the hair flowed over in a river of molten gold. Like nature busily abhorring a vacuum, Mitchell flooded space that ought perhaps to have been filled by an array of other women before her: the role of thoughtful, poetically articulate, unsentimental, insubordinate, self-expressive female countercultural pop icon. It was a tough job and maybe Mitchell didn’t ask for it, but she certainly got it and then did it with never less than questioning commitment.

Mitchell settled in the imaginations of pop listeners in the early 70s. In the UK, “Big Yellow Taxi” was a biggish hit in the summer of 1970, its glassily sardonic reflections upon humanity’s relationship with the environment marking out the flaxen-haired Scando-Canadian hippie-chick who sang it as a poster girl for a certain kind of wholesome big-R Romanticism. She was fey, frowning, Nordically bony, the perfect package for the deal: a one-take archetype. What the songs didn’t articulate and the voice didn’t swoop upon like a slender bird, the hair flowed over in a river of molten gold. Like nature busily abhorring a vacuum, Mitchell flooded space that ought perhaps to have been filled by an array of other women before her: the role of thoughtful, poetically articulate, unsentimental, insubordinate, self-expressive female countercultural pop icon. It was a tough job and maybe Mitchell didn’t ask for it, but she certainly got it and then did it with never less than questioning commitment.

more here.

Jacques Derrida: The Problems of Presence

Derek Attridge at the TLS:

In 1962 Derrida published a book-length introduction to his translation of Husserl’s short work The Origin of Geometry in which the seeds of his later thinking were already evident, but it was in 1967 that he truly made his mark on the French philosophical scene. In that year he published no fewer than three books, and in so doing displayed the startling originality and productiveness that was to characterize his career until his death from pancreatic cancer in 2004: L’écriture et la difference, La voix et le phénomène and De la grammatologie. Five years later, another trio of books appeared, cementing Derrida’s position at the forefront of what became known in the English-speaking world as “post-structuralism”: La Dissemination, Marges de la philosophie and Positions. There followed a steady stream of publications; a recent posthumous volume produced by his favourite French publisher, Galilée, lists fifty-seven books from their own house and another thirty-one from other publishers – and this list includes only the first two volumes in the planned series of hitherto unpublished seminars delivered over more than forty years.

In 1962 Derrida published a book-length introduction to his translation of Husserl’s short work The Origin of Geometry in which the seeds of his later thinking were already evident, but it was in 1967 that he truly made his mark on the French philosophical scene. In that year he published no fewer than three books, and in so doing displayed the startling originality and productiveness that was to characterize his career until his death from pancreatic cancer in 2004: L’écriture et la difference, La voix et le phénomène and De la grammatologie. Five years later, another trio of books appeared, cementing Derrida’s position at the forefront of what became known in the English-speaking world as “post-structuralism”: La Dissemination, Marges de la philosophie and Positions. There followed a steady stream of publications; a recent posthumous volume produced by his favourite French publisher, Galilée, lists fifty-seven books from their own house and another thirty-one from other publishers – and this list includes only the first two volumes in the planned series of hitherto unpublished seminars delivered over more than forty years.

more here.

Delacroix: Romanticism’s Unruly Hero

Jed Perl at the NYRB:

Color is Eugène Delacroix’s hero. He fights for color. He lives for color. His oil paintings are luxurious orchestrations of feverish reds, velvety blues, dusky purples, astringent oranges, and shimmering greens. In his works on paper, some of the same colors, presented as isolated elements, become refreshingly austere. There is nothing that this giant of nineteenth-century French painting cannot do with color. If his art is uneasy, it’s because his color is never easy. He flirts with chromatic chaos. He yearns for chromatic catharsis. “The very sight of my palette,” he once wrote, “freshly set out with the colors in their contrasts is enough to fire my enthusiasm.” However alien we may find some of his gaudy fantasies and megalomaniacal ambitions, there is no question that he is an artist who knows how to fill our eyes.

What’s demoralizing about the retrospective that is currently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is that Delacroix’s coloristic genius is so hard to find. The sepulchral installation muffles and sometimes even strangles his work. Is this the museum’s idea of what it takes to set a mood worthy of Delacroix’s reputation as the leader of the Romantic movement in France?

more here.

What Does It Mean to Be Self-Actualized in the 21st Century?

Scott Barry Kaufman in Scientific American:

Many people are familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, in which he argued that basic needs such as safety, belonging, and self-esteem must be satisfied (to a reasonable healthy degree) before being able to fully realize one’s unique creative and humanitarian potential. What many people may not realize is that a strict hierarchy was not really the focus of his work (and in fact, he never represented his theory as a pyramid).

Many people are familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, in which he argued that basic needs such as safety, belonging, and self-esteem must be satisfied (to a reasonable healthy degree) before being able to fully realize one’s unique creative and humanitarian potential. What many people may not realize is that a strict hierarchy was not really the focus of his work (and in fact, he never represented his theory as a pyramid).

…Overall, self-actualization was related to higher levels of stability and the ability to protect your highest level goals from disruption by distracting impulses and thoughts. Self-actualization was related to lower levels of disruptive impulsivity (“Get out of control”, “Am self-destructive”), nonconstructive thinking (“Have a dark outlook on the future”, “Often express doubts”), and a lack of authenticity and meaning (“Feel that my list lacks direction”, “Act or feel in a way that does not fit me”). Just as Maslow predicted, those with higher self-actualization scores were much more motivated by growth, exploration, and love of humanity than the fulfillment of deficiencies in basic needs. What’s more, self-actualization scores were associated with multiple indicators of well-being, including greater life satisfaction, curiosity, self-acceptance, positive relationships, environmental mastery, personal growth, autonomy, and purpose in life.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Tiny Bird

The urge to be a tiny bird

upon a tiny limb, maybe

a bridled titmouse

standing on its spidery feet,

not a big guy who falls

with a resounding thump

and bruises sidewalks and pastures,

sinks in river mud to the waist.

If my feet were spears I would have descended

to a tumultuous underground river that are

everywhere, earth-borne by the black current.

When young I thought I’d die in my thirties

like so many of my favorite poets.

At seventy-five I see this hasn’t happened.

Still, I am faithful to my poems and birds.

Birds are poems I haven’t caught yet.

Jim Harrison

from Dead Man’s Float

Copper Canyon Press, 2015

Faith and the Fear of Death

Jonathan Jong in The New Atlantis:

The line primus in orbe deos fecit timor — “fear first made gods in the world” — appears in at least two Latin poems in the first century. Earlier it was expressed with great aplomb in Lucretius’s poem On the Nature of Things. For Lucretius, as for many thinkers since, what terrifies us is nature — the fickleness of seed and season, the wrath of storm and sea. At least since Freud, however, the fear of death, or cessation of the self, has been a more common theoretical fascination — “Man’s tomb is the sole birthplace of the gods,” according to Ludwig Feuerbach. I picked up the idea from a group of psychologists working on what they called “terror management theory,” an attempt to explain human behavior in terms of responses to the fear of death. They in turn had picked the idea up from Ernest Becker, an American cultural anthropologist working in the Sixties and early Seventies.

Becker’s book The Denial of Death won the 1974 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction just two months after he died of cancer, aged forty-nine. The book advanced the theory that the knowledge and fear of death is humanity’s central driving force, underlying civilization and all human achievement. According to Becker, we are unique among animals in our awareness of our mortality. This knowledge leads us to construct systems of values — theological, moral, political, cultural, scientific — through which we can deny our finitude. All endeavors within these systems are attempts to obtain immortality, whether literal or symbolic. The terror management theorists turned Becker’s sweeping analysis into a scientific theory amenable to empirical testing. One experiment in a 1989 study involved twenty-two municipal court judges who were asked to set bail in the case of a hypothetical woman charged with prostitution. The judges were given identical prosecutor’s notes describing the case, but half of the judges, randomly selected, also received instructions to imagine and write about what dying would be like and how these thoughts about death made them feel. The other half were spared any prompted thoughts about mortality. While the judges in the neutral condition set bail at an average of $50, the judges who were asked to contemplate death set bail at $455, over nine times higher. The researchers concluded that this showed that thinking about death made the judges more punitive against someone accused of violating a moral norm, confirming the idea that strengthening moral norms is part of what we do when we are anxious about our finitude.

More here.

Wednesday, November 14, 2018

Martin Rees: what are the limits of human understanding?

Martin Rees in Prospect:

In cosmological or Darwinian terms, a millennium is but an instant. So let us fast forward not for a few centuries or millennia, but for an astronomical timescale millions of times longer than that. The stellar births and deaths in our galaxy will gradually proceed more slowly, until jolted by the environmental shock of an impact with the Andromeda Galaxy, maybe four billion years hence. The debris of our galaxy, Andromeda and their smaller companions—which now make up what is called the Local Group—will thereafter aggregate into one amorphous swarm of stars. Many billions of years after that, gravitational attraction will be overwhelmed by a mysterious force latent in empty space that pushes galaxies apart from each other. Galaxies accelerate away and disappear over a horizon. All that will be left in view, after 100bn years, will be the dead and dying stars of our Local Group, which could continue for trillions of years. Against the darkening background, sub-atomic particles such as protons may decay, dark matter particles annihilate and black holes evaporate—and then silence.

In cosmological or Darwinian terms, a millennium is but an instant. So let us fast forward not for a few centuries or millennia, but for an astronomical timescale millions of times longer than that. The stellar births and deaths in our galaxy will gradually proceed more slowly, until jolted by the environmental shock of an impact with the Andromeda Galaxy, maybe four billion years hence. The debris of our galaxy, Andromeda and their smaller companions—which now make up what is called the Local Group—will thereafter aggregate into one amorphous swarm of stars. Many billions of years after that, gravitational attraction will be overwhelmed by a mysterious force latent in empty space that pushes galaxies apart from each other. Galaxies accelerate away and disappear over a horizon. All that will be left in view, after 100bn years, will be the dead and dying stars of our Local Group, which could continue for trillions of years. Against the darkening background, sub-atomic particles such as protons may decay, dark matter particles annihilate and black holes evaporate—and then silence.

As we attempt to grapple with this bleak post-human future, we must also confront the question of what humans can hope to understand. Parts of the physical world are understood. They can be observed and described by theories—but much of it cannot. Human observation bumps up against stark limits. Human reasoning is not limitless either, but it does allow us to think through what might in principle be “over the horizon.”

More here.

The plastic backlash: what’s behind our sudden rage – and will it make a difference?

Stephen Buranyi in The Guardian:

Plastic is everywhere, and suddenly we have decided that is a very bad thing. Until recently, plastic enjoyed a sort of anonymity in ubiquity: we were so thoroughly surrounded that we hardly noticed it. You might be surprised to learn, for instance, that today’s cars and planes are, by volume, about 50% plastic. More clothing is made out of polyester and nylon, both plastics, than cotton or wool. Plastic is also used in minute quantities as an adhesive to seal the vast majority of the 60bn teabags used in Britain each year.

Plastic is everywhere, and suddenly we have decided that is a very bad thing. Until recently, plastic enjoyed a sort of anonymity in ubiquity: we were so thoroughly surrounded that we hardly noticed it. You might be surprised to learn, for instance, that today’s cars and planes are, by volume, about 50% plastic. More clothing is made out of polyester and nylon, both plastics, than cotton or wool. Plastic is also used in minute quantities as an adhesive to seal the vast majority of the 60bn teabags used in Britain each year.

Add this to the more obvious expanse of toys, household bric-a-brac and consumer packaging, and the extent of plastic’s empire becomes clear. It is the colourful yet banal background material of modern life. Each year, the world produces around 340m tonnes of the stuff, enough to fill every skyscraper in New York City. Humankind has produced unfathomable quantities of plastic for decades, first passing the 100m tonne mark in the early 1990s. But for some reason it is only very recently that people have really begun to care.

The result is a worldwide revolt against plastic, one that crosses both borders and traditional political divides.

More here.

The Voice of the ‘Intellectual Dark Web’

Amelia Lester in Politico:

One evening this fall at a house in West Hollywood, the Australian editor and writer Claire Lehmann had dinner with the neuroscientist Sam Harris and Eric Weinstein, the managing director of tech entrepreneur Peter Thiel’s investment firm. Joe Rogan, the podcast host, joined later on, when the group decamped to a comedy club.

One evening this fall at a house in West Hollywood, the Australian editor and writer Claire Lehmann had dinner with the neuroscientist Sam Harris and Eric Weinstein, the managing director of tech entrepreneur Peter Thiel’s investment firm. Joe Rogan, the podcast host, joined later on, when the group decamped to a comedy club.

You could think of the gathering as a board meeting of sorts for the “intellectual dark web,” or IDW, a loose cadre of academics, journalists and tech entrepreneurs who view themselves as standing up to the knee-jerk left-leaning politics of academia and the media. Over the past year, the IDW has arisen as a puzzling political force, made up of thinkers who support “Enlightenment values” and accuse the left of setting dangerously illiberal limits on acceptable thought. The IDW has defined itself mainly by diving into third-rail topics like the genetics of gender and racial difference—territory that seems even more fraught in the era of #MeToo and the Trump resistance. But part of the attraction of the IDW is the sense that many more people agree with its principles than can come forward publicly: The dinner host on this night, Lehmann says, was a famous person she would prefer not to name.

More here.

Marcin Patrzalek: Beethoven’s 5th Symphony on One Guitar

‘Against the Clock’ by Derek Mahon

Magdalena Kay at the Dublin Review of Books:

Derek Mahon’s new volume of poems, Against the Clock, again proves him one of the greatest contemporary masters of poetic form. Preoccupied as he is with his advancing age and the “final deadline” looming in the future, the suppleness and subtleness of his flexible rhythms and rhymes keep the subject from becoming ponderous. Mahon knows all about the dark side of life, but has an extraordinary ability to set his style against it, as it were, so that his formal ingenuity provides a counterweight. It would be false to say that the darkness is vanquished ‑ it is not. A Mahon poem does not engage in illusionary antics or light-headed optimism. It knows the type of world in which it must reside. But its own energy carries it through with panache: “life is short and time, the great reminder, / closes the file of new poems in line / for the printer and binder” ‑ and these lines in parenthesis no less. Rhymes as unusual as “reminder” and “binder” abound in this volume, and display one of Mahon’s greatest talents: his ability to take so-called traditional forms and subject them to change and play. At this point in his career it seems effortless. His play with the units of poetic form is creative to the point of ingenuity ‑ but not quite, since Mahon sets himself against ingenuity for its own sake, or wordplay that is not anchored by deep feeling. And yet “play” is the right word for what this serious poet allows himself to do, and perhaps must do.

Derek Mahon’s new volume of poems, Against the Clock, again proves him one of the greatest contemporary masters of poetic form. Preoccupied as he is with his advancing age and the “final deadline” looming in the future, the suppleness and subtleness of his flexible rhythms and rhymes keep the subject from becoming ponderous. Mahon knows all about the dark side of life, but has an extraordinary ability to set his style against it, as it were, so that his formal ingenuity provides a counterweight. It would be false to say that the darkness is vanquished ‑ it is not. A Mahon poem does not engage in illusionary antics or light-headed optimism. It knows the type of world in which it must reside. But its own energy carries it through with panache: “life is short and time, the great reminder, / closes the file of new poems in line / for the printer and binder” ‑ and these lines in parenthesis no less. Rhymes as unusual as “reminder” and “binder” abound in this volume, and display one of Mahon’s greatest talents: his ability to take so-called traditional forms and subject them to change and play. At this point in his career it seems effortless. His play with the units of poetic form is creative to the point of ingenuity ‑ but not quite, since Mahon sets himself against ingenuity for its own sake, or wordplay that is not anchored by deep feeling. And yet “play” is the right word for what this serious poet allows himself to do, and perhaps must do.

more here.

James Baldwin’s Optimism

Gabrielle Bellot at The Paris Review:

“Every poet is an optimist,” Baldwin told Hugh Hebert at the Guardian when Beale Street was published. And yet, Baldwin continued, “you have to reach a certain level of despair to deal with your life at all … If you’re black, and short, and ugly, and pop-eyed, and you think maybe you’re homosexual though you don’t know the word, and you’ve got to support a family because your father is dying—that’s a stacked deal.”

“Every poet is an optimist,” Baldwin told Hugh Hebert at the Guardian when Beale Street was published. And yet, Baldwin continued, “you have to reach a certain level of despair to deal with your life at all … If you’re black, and short, and ugly, and pop-eyed, and you think maybe you’re homosexual though you don’t know the word, and you’ve got to support a family because your father is dying—that’s a stacked deal.”

Baldwin’s glimmer of faith in the world he volcanically condemned was even more extraordinary because, though the deck was stacked against him, he resisted succumbing to despair. This is perhaps best exemplified in the resonant ending to one of his best-known fictions, the 1957 short story “Sonny’s Blues,” in which Sonny—sent to jail when the story starts for dealing heroin and plagued by a toxic relationship with his brother (the narrator)—ends up having a gentle, loving moment with his sibling in a jazz bar. For a long time, Sonny had wanted to learn to play jazz rather than follow the more traditional route of going to school, as his brother had; the narrator, partly because he knew little about jazz, disapproved of Sonny’s musical inclinations and continued heroin use, which Sonny claimed helped him play.

more here.

The Great Nadar

Emilie Bickerton at the LRB:

‘Like the knives of Chinese jugglers’, Charles Bataille said of his friend Félix Nadar, ‘turbulent, unexpected, terrifying’. Adam Begley’s biography describes a life lived so frenetically, it’s surprising it lasted so long – Nadar died at the age of ninety, in 1910. Yet he is remembered today primarily for the stillness and serenity of his photographic portraits of 19th-century Parisian luminaries. ‘You’ve done better than I’ve ever done,’ the physician Philippe Ricord wrote in the livre d’or, an autograph book Nadar kept for clients to sign in his studio at 35 boulevard des Capucines, ‘for I’ve always found it impossible to resemble myself from one day to the next.’ This is what Nadar was interested in, the search for what he called ‘an intimate resemblance’ – an instant not merely captured, but in a way that caught something essential in his subjects.

‘Like the knives of Chinese jugglers’, Charles Bataille said of his friend Félix Nadar, ‘turbulent, unexpected, terrifying’. Adam Begley’s biography describes a life lived so frenetically, it’s surprising it lasted so long – Nadar died at the age of ninety, in 1910. Yet he is remembered today primarily for the stillness and serenity of his photographic portraits of 19th-century Parisian luminaries. ‘You’ve done better than I’ve ever done,’ the physician Philippe Ricord wrote in the livre d’or, an autograph book Nadar kept for clients to sign in his studio at 35 boulevard des Capucines, ‘for I’ve always found it impossible to resemble myself from one day to the next.’ This is what Nadar was interested in, the search for what he called ‘an intimate resemblance’ – an instant not merely captured, but in a way that caught something essential in his subjects.

A few pictures have come to represent Nadar’s work: Charles Baudelaire, undated, but probably between 1855 and 1862, standing in his elegant dark coat, half-unbuttoned waistcoat and bow tie, hands in pockets, staring back at the camera – defiant perhaps, but with the mouth and the eyes, which Nadar called ‘two drops of coffee’, betraying some vulnerability.

more here.

Wednesday Poem

Afternoon Tea

I look forward to offering,

Glimpses of my land,

To our foreign neighbors –

Our white-wide-eyed friends,

Laughing at jokes private to myself,

Knowing a couple of things,

Or more than they, do.

But when I am your wife,

Second half of your life,

I falter, I don’t know why,

But I cease to find a self of mine.

There stops being an ‘I’,

When I am your wife.

(I don’t, just don’t know, why)

Somehow I feel the need to snatch,

That expert opinion of the secret of my long beautiful hair,

From your superior mouth.

That anecdote,

The knowledge nugget,

That no one cares about, really.

And my India, is not your India,

And our India is different too.

You can narrate the dusty traffic,

And I can relate to lazy noons.

Why should we struggle, I wonder,

On the exact degree of which spice,

And at the end why do we just resign,

To a word of marriage as our excuse,

Of all our bruised social contracts?

As your wife,

Is not that the same

For you,

As my husband?

There is no fault of you,

(or at least not completely)

My wife-ness needs a you,

But not the ‘I-ness’, true.

I witness a war of pronouns –

Where is the I, the we, the me, the you,

In the folk stories of that land,

In the blue eyes of friends,

In the polite smiles of guests?

Who does even India belong to,

To me, or all of you?

It seeps into an unthought,

Hovering in my non-senses,

Its sting is felt acutely,

In days as normal,

As happy, as exciting,

As today.

.

by Anam Akhter

Enough With All the Innovation

John Patrick Leary in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

At Wayne State University, a commuter campus in Detroit where faculty members and students struggle to turn people out for events, the opening of the Innovation Hub last fall was a big deal. I have rarely seen so many people in one room on campus. Speakers gushed about the university’s “innovation ecosystem” and the “disruptive” start-ups sure to blossom in its “incubators.” Speakers paced the stage giving TED-style speeches rich in the soothing platitudes of business books. To nurture innovation, explained one, “you’ve got to have serendipity and creativity, and that’s when two plus two equals seven — apologies to the math department,” he added, chuckling at his own baffling joke. “You’ve heard the word ‘innovation’ a lot so far this evening,” said another, apologetically, briefly giving me hope that the term would finally be defined, or better yet, discarded. He continued: “You’re about to hear it a lot more.”

At Wayne State University, a commuter campus in Detroit where faculty members and students struggle to turn people out for events, the opening of the Innovation Hub last fall was a big deal. I have rarely seen so many people in one room on campus. Speakers gushed about the university’s “innovation ecosystem” and the “disruptive” start-ups sure to blossom in its “incubators.” Speakers paced the stage giving TED-style speeches rich in the soothing platitudes of business books. To nurture innovation, explained one, “you’ve got to have serendipity and creativity, and that’s when two plus two equals seven — apologies to the math department,” he added, chuckling at his own baffling joke. “You’ve heard the word ‘innovation’ a lot so far this evening,” said another, apologetically, briefly giving me hope that the term would finally be defined, or better yet, discarded. He continued: “You’re about to hear it a lot more.”

It was a success: Students were excited, the free food was unusually good, and the whole production could have probably paid for a couple of adjunct history professors. I left disheartened by it all: the unskeptical embrace of buzzwords, the unexamined enthusiasm for the marketplace as a wise referee of ideas. I also wondered whether the reason students were so enthusiastic about running a potentially lucrative start-up at school was that their Wayne State education wasn’t as affordable as it was two decades ago, when the state of Michigan accounted for two-thirds of the university’s operating budget, as opposed to one-third today. Private universities like Princeton, Yale, the University of Pennsylvania, New York University, and Rice are locked in what some have called an “innovation arms race,”competing to open new entrepreneurial “labs,” “hubs,” and “makerspaces” to facilitate student and faculty start-ups. Public universities like mine are racing to keep up. The Innovation Hub is part of a major new initiative, explained university officials in a statement, to “prepare our students with innovation and entrepreneurship skills” while also leading “the revitalization of the Detroit region.”

More here.

‘Reprogrammed’ stem cells implanted into patient with Parkinson’s disease

David Cyranoski in Nature:

Japanese neurosurgeons have implanted ‘reprogrammed’ stem cells into the brain of a patient with Parkinson’s disease for the first time. The condition is only the second for which a therapy has been trialled using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which are developed by reprogramming the cells of body tissues such as skin so that they revert to an embryonic-like state, from which they can morph into other cell types. Scientists at Kyoto University use the technique to transform iPS cells into precursors to the neurons that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine. A shortage of neurons producing dopamine in people with Parkinson’s disease can lead to tremors and difficulty walking.

Japanese neurosurgeons have implanted ‘reprogrammed’ stem cells into the brain of a patient with Parkinson’s disease for the first time. The condition is only the second for which a therapy has been trialled using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which are developed by reprogramming the cells of body tissues such as skin so that they revert to an embryonic-like state, from which they can morph into other cell types. Scientists at Kyoto University use the technique to transform iPS cells into precursors to the neurons that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine. A shortage of neurons producing dopamine in people with Parkinson’s disease can lead to tremors and difficulty walking.

In October, neurosurgeon Takayuki Kikuchi at Kyoto University Hospital implanted 2.4 million dopamine precursor cells into the brain of a patient in his 50s. In the three-hour procedure, Kikuchi’s team deposited the cells into 12 sites, known to be centres of dopamine activity. Dopamine precursor cells have been shown to improve symptoms of Parkinson’s disease in monkeys. Stem-cell scientist Jun Takahashi and colleagues at Kyoto University derived the dopamine precursor cells from a stock of IPS cells stored at the university. These were developed by reprogramming skin cells taken from an anonymous donor. “The patient is doing well and there have been no major adverse reactions so far,” says Takahashi. The team will observe him for six months and, if no complications arise, will implant another 2.4 million dopamine precursor cells into his brain. The team plans to treat six more patients with Parkinson’s disease to test the technique’s safety and efficacy by the end of 2020.

More here.

Tuesday, November 13, 2018

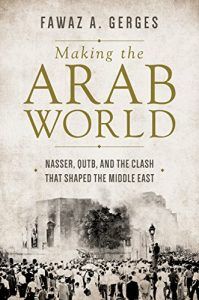

The Rivalry That Shaped Modern Egypt

Shadi Hamid in Foreign Affairs:

Seven years since the heady days of early 2011, when massive, electrifying protests brought down the Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak, the political atmosphere in Egypt has turned somber. In 2013, General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi overthrew President Mohamed Morsi, a leader of the Muslim Brotherhood who had narrowly won Egypt’s first free presidential election the prior year. Since seizing power, Sisi has emptied the country of any real politics. His crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood has been particularly brutal: he has jailed tens of thousands of Brothers, and designated the group a terrorist organization. On the regional stage, Egypt has found itself relegated to second-tier status. What was once the center of the Arab world today feels like a ghost of its former self.

Seven years since the heady days of early 2011, when massive, electrifying protests brought down the Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak, the political atmosphere in Egypt has turned somber. In 2013, General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi overthrew President Mohamed Morsi, a leader of the Muslim Brotherhood who had narrowly won Egypt’s first free presidential election the prior year. Since seizing power, Sisi has emptied the country of any real politics. His crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood has been particularly brutal: he has jailed tens of thousands of Brothers, and designated the group a terrorist organization. On the regional stage, Egypt has found itself relegated to second-tier status. What was once the center of the Arab world today feels like a ghost of its former self.

In this environment, it is easy to forget that for much of the twentieth century, Egypt was the most consequential battleground in the struggle for the soul of the new Arab state. Following the formal dissolution of the Ottoman caliphate, in 1924, new ideologies and approaches to governing competed to fill the vacuum. In the 1930s and 1940s, during Egypt’s so-called liberal era, secularists, socialists, and Islamists vied for legitimacy in a chaotic but relatively free political atmosphere. The freedom did not last. In 1952, a clandestine cohort of young military officers led by a man named Gamal Abdel Nasser overthrew the Egyptian monarchy and eventually ended what little was left of Egypt’s liberal age.

More here.

The origins of Earth’s water are a big mystery—but we may have one more piece of the puzzle

Neel V. Patel in Popular Science:

In a new paper published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, Arizona State University researchers suggest that water on Earth originated from material brought by asteroids, assisted by some leftover gas strewn about after the sun’s formation.

In a new paper published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, Arizona State University researchers suggest that water on Earth originated from material brought by asteroids, assisted by some leftover gas strewn about after the sun’s formation.

This is certainly far from the first time people have suggested water as we know it (and drink) it has an extraterrestrial origin. Historically, the easiest explanation has been that all of Earth’s water came from asteroids that impacted the Earth during the early days of its 4.6 billion year life. Why? Water from Earth shares the same chemical signatures as water found in asteroids—specifically, the ratio of deuterium (a heavy hydrogen isotope) to normal hydrogen. And previous experiments have shown that, in spite of all the heat and energy created by these massively powerful collisions, that water could have been preserved as it found itself on the yet-to-be-blue planet.

Still, those theories have never been quite enough to fill in some of the other blind spots we have about water’s origin. The hydrogen found in Earth’s oceans isn’t necessarily the same sort of hydrogen present throughout the rest of the planet—samples collected closer to the Earth’s core possess exceedingly low amounts of deuterium, which seems to suggest this hydrogen didn’t come from asteroid impacts.

More here.

A Hundred Years After the Armistice

Adam Hochschild in The New Yorker:

For millions of soldiers, the First World War meant unimaginable horror: artillery shells that could pulverize a human body into a thousand fragments; immense underground mine explosions that could do the same to hundreds of bodies; attacks by poison gas, tanks, flamethrowers. Shortly after 8 p.m. on November 7, 1918, however, French troops near the town of La Capelle saw something different. From the north, three large automobiles, with the black eagle of Imperial Germany on their sides, approached the front lines with their headlights on. Two German soldiers were perched on the running boards of the lead car, one waving a white flag, the other, with an unusually long silver bugle, blowing the call for ceasefire—a single high tone repeated in rapid succession four times, then four times again, with the last note lingering.

For millions of soldiers, the First World War meant unimaginable horror: artillery shells that could pulverize a human body into a thousand fragments; immense underground mine explosions that could do the same to hundreds of bodies; attacks by poison gas, tanks, flamethrowers. Shortly after 8 p.m. on November 7, 1918, however, French troops near the town of La Capelle saw something different. From the north, three large automobiles, with the black eagle of Imperial Germany on their sides, approached the front lines with their headlights on. Two German soldiers were perched on the running boards of the lead car, one waving a white flag, the other, with an unusually long silver bugle, blowing the call for ceasefire—a single high tone repeated in rapid succession four times, then four times again, with the last note lingering.

By prior agreement, the three German cars slowly made their way across the scarred and cratered no man’s land between the opposing armies. When they reached the French lines, they halted, the German bugler was replaced by a French one (his bugle is in a Paris museum today), and the German peace envoys continued their journey. At La Capelle, flashes lit up the night as the envoys were photographed by waiting press and newsreel cameramen, then transferred to French cars. Their route took them past houses, factories, barns, and churches reduced to charred rubble, fruit trees cut down and wells poisoned by retreating German troops.

More here.