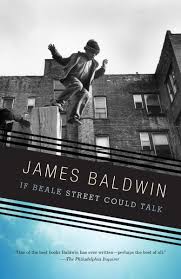

Gabrielle Bellot at The Paris Review:

“Every poet is an optimist,” Baldwin told Hugh Hebert at the Guardian when Beale Street was published. And yet, Baldwin continued, “you have to reach a certain level of despair to deal with your life at all … If you’re black, and short, and ugly, and pop-eyed, and you think maybe you’re homosexual though you don’t know the word, and you’ve got to support a family because your father is dying—that’s a stacked deal.”

“Every poet is an optimist,” Baldwin told Hugh Hebert at the Guardian when Beale Street was published. And yet, Baldwin continued, “you have to reach a certain level of despair to deal with your life at all … If you’re black, and short, and ugly, and pop-eyed, and you think maybe you’re homosexual though you don’t know the word, and you’ve got to support a family because your father is dying—that’s a stacked deal.”

Baldwin’s glimmer of faith in the world he volcanically condemned was even more extraordinary because, though the deck was stacked against him, he resisted succumbing to despair. This is perhaps best exemplified in the resonant ending to one of his best-known fictions, the 1957 short story “Sonny’s Blues,” in which Sonny—sent to jail when the story starts for dealing heroin and plagued by a toxic relationship with his brother (the narrator)—ends up having a gentle, loving moment with his sibling in a jazz bar. For a long time, Sonny had wanted to learn to play jazz rather than follow the more traditional route of going to school, as his brother had; the narrator, partly because he knew little about jazz, disapproved of Sonny’s musical inclinations and continued heroin use, which Sonny claimed helped him play.

more here.