Kelly and Zach Weinersmith in Delancyplace:

Let’s talk about mirror humans: “Oh, you haven’t heard of mirror humans? Let’s back up a moment.

Let’s talk about mirror humans: “Oh, you haven’t heard of mirror humans? Let’s back up a moment.

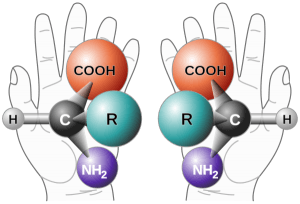

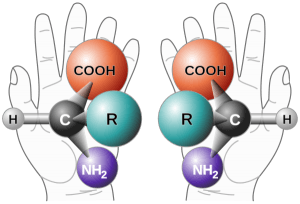

“Life is made of lots of little molecules, and these molecules make up important bigger molecules, like DNA, RNA, and proteins. Some molecules exhibit what is called chirality, from the Greek word for ‘hand.’ If a molecule has chirality that basically means there is a mirror version of it. “To wrap your head around ‘mirror versions’ of things, think about your hands. They look exactly the same, but no matter how you rotate your left hand, it won’t be exactly the same as the right. If you have your palms up, your left thumb will point left and your right thumb will point right. Each hand has all the same parts, but they are flipped, as if through a mirror. “When you have two molecules that are mirror images of one another, one of these molecules is designated as the left-handed version and the other as the right-handed version. Intriguingly, life seems to favor a certain handedness for particular tasks. For example, almost all amino acids (which you may remember from previous chapters are the building blocks of proteins) are in the left-handed form. Why nature abhors right-handed amino acids is a topic of debate, but even the amino acids we find in space tend to be left-handed.

“But screw nature. Whatever her reasoning is, there is no known physical reason we couldn’t create an organism out of completely opposite-handed molecules in the lab — a ‘mirror organism,’ if you like. Some scientists, including Dr. [George] Church [of Harvard], are working to create (simple) mirror organisms, with the hope creating larger and larger such creatures. Why exactly would we want this? Well, for one, it’s awesome. You create something that looks like a nice little kitty, but is totally incompatible with the rest of the life on the planet, perhaps even the universe. For example, mirror-opposite organisms would need to eat mirror food in order to be able to digest it. They would also be undigestible to all predators. Best of all, a mirror-opposite organism would be completely immune to all diseases, because all living parasites and pathogens evolved to infect organisms with normal chirality.

“And if it worked, hey, we could scale up to making mirror-opposite humans.

More here.

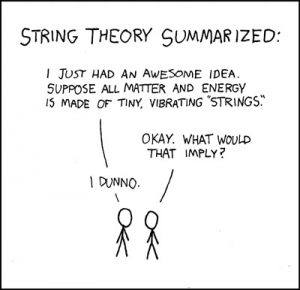

Way back in 1996 science writer John Horgan published The End of Science, in which he made the argument that various fields of science were running up against obstacles to any further progress of the magnitude they had previously experienced. One can argue about other fields (please don’t do it here…), but for the field of theoretical high energy physics, Horgan had a good case then, one that has become stronger and stronger as time goes on.

Way back in 1996 science writer John Horgan published The End of Science, in which he made the argument that various fields of science were running up against obstacles to any further progress of the magnitude they had previously experienced. One can argue about other fields (please don’t do it here…), but for the field of theoretical high energy physics, Horgan had a good case then, one that has become stronger and stronger as time goes on.

Among the string of resignations triggered by the draft Brexit agreement with the European Union (EU), one stood out. In a double whammy for an embattled Prime Minister, Rehman Chishti the MP for Gillingham and Rainham resigned as both Vice Chairman of the Conservative Party as well as the PM’s Trade Envoy to Pakistan. Aside from citing Theresa May’s shambolic handling of Brexit negotiations,

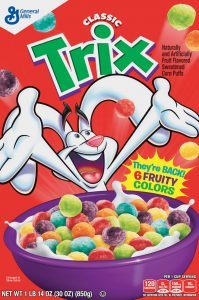

Among the string of resignations triggered by the draft Brexit agreement with the European Union (EU), one stood out. In a double whammy for an embattled Prime Minister, Rehman Chishti the MP for Gillingham and Rainham resigned as both Vice Chairman of the Conservative Party as well as the PM’s Trade Envoy to Pakistan. Aside from citing Theresa May’s shambolic handling of Brexit negotiations,  In 2015, General Mills reformulated Trix with “natural” colors. Customers complained that the bright hues of their childhood cereal were now dull yellows and purples. Two years later, the company released Classic Trix to stand on store shelves alongside so-called No, No, No Trix, the natural version. This nickname, promising “no tricks,” sounds abstemious; the virtuous customer says no to technicolor temptation. But Trix customers wanted their colors back. As one Tweet put it: “I mean, I get that artificial flavors are bad and all that shiz, but man I miss neon colored Trix.”

In 2015, General Mills reformulated Trix with “natural” colors. Customers complained that the bright hues of their childhood cereal were now dull yellows and purples. Two years later, the company released Classic Trix to stand on store shelves alongside so-called No, No, No Trix, the natural version. This nickname, promising “no tricks,” sounds abstemious; the virtuous customer says no to technicolor temptation. But Trix customers wanted their colors back. As one Tweet put it: “I mean, I get that artificial flavors are bad and all that shiz, but man I miss neon colored Trix.” The line of French painting that stretches from Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People to Pablo Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon (or from Camille Corot early in the 1820s to Henri Matisse on the eve of the First World War) is a unique episode in recent history. It has established itself as “world-historical,” to borrow a term from G. W. F. Hegel. That is, it continues to speak to aspects—distinctive features—of the modern condition which succeeding ages seem unable to bring into focus, or go on valuing and properly criticizing, without its aid. The tradition’s only rival, if this is the standard, may be German music from Johann Sebastian Bach to Richard Wagner.

The line of French painting that stretches from Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People to Pablo Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon (or from Camille Corot early in the 1820s to Henri Matisse on the eve of the First World War) is a unique episode in recent history. It has established itself as “world-historical,” to borrow a term from G. W. F. Hegel. That is, it continues to speak to aspects—distinctive features—of the modern condition which succeeding ages seem unable to bring into focus, or go on valuing and properly criticizing, without its aid. The tradition’s only rival, if this is the standard, may be German music from Johann Sebastian Bach to Richard Wagner. Timbaland and Elliott developed a grammar, collecting extra-musical noises—sighs, women giggling, coughs, babies gurgling—and stacking them so that they became instruments in and of themselves. They weren’t afraid to experiment with sounds that were nearer to the grotesque than the beautiful. One of the most well known is the

Timbaland and Elliott developed a grammar, collecting extra-musical noises—sighs, women giggling, coughs, babies gurgling—and stacking them so that they became instruments in and of themselves. They weren’t afraid to experiment with sounds that were nearer to the grotesque than the beautiful. One of the most well known is the  The stunning failure of a once-promising cancer drug has got some researchers arguing that the field has moved too fast in its embrace of therapies that unleash the immune system. The drug, epacadostat,

The stunning failure of a once-promising cancer drug has got some researchers arguing that the field has moved too fast in its embrace of therapies that unleash the immune system. The drug, epacadostat,  Let’s talk about mirror humans: “Oh, you haven’t heard of mirror humans? Let’s back up a moment.

Let’s talk about mirror humans: “Oh, you haven’t heard of mirror humans? Let’s back up a moment. One afternoon in

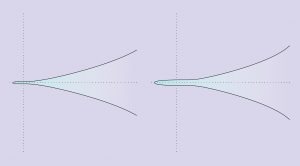

One afternoon in  Elliptic curves seem to admit infinite variety, but they really only come in two flavors. That is the upshot of a new proof from a graduate student at Harvard University.

Elliptic curves seem to admit infinite variety, but they really only come in two flavors. That is the upshot of a new proof from a graduate student at Harvard University. New York’s governor, Andrew Cuomo, just announced a bail-reform program. Details were not yet available at press time, but it’s clear that Cuomo intends to release thousands of arrested persons, even suspected felons, without bail.

New York’s governor, Andrew Cuomo, just announced a bail-reform program. Details were not yet available at press time, but it’s clear that Cuomo intends to release thousands of arrested persons, even suspected felons, without bail. Hannah Arendt reflected on the significance of humanity’s desire for the stars in her 1963 essay “

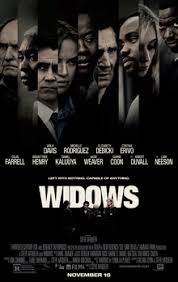

Hannah Arendt reflected on the significance of humanity’s desire for the stars in her 1963 essay “ It occurred to me, when thinking about Ronnie’s bathroom scene, that this is not McQueen’s first time depicting the repressed, deep-seated trauma of a wealthy but unhappy individual on film: that Shame, whose central character appeared to have developed sex-addiction in the wake of some unspecified, formative trauma—maybe psychic, maybe physical—addressed a similar, if not entirely symmetrical, ache. The sex addict, Brandon, as played in the key of Patrick Bateman by the Irish actor Michael Fassbender, also contained his introspection and his self-injurious anger within the confines of the bathroom. Often, his releases there were masturbatory. So, on some level, was the movie; lacking detailed and elucidating background information, Brandon’s tragedy became the tragedy of a successful, very handsome white man tortured by the need to regularly have sex with one or more women who resemble fashion models. (Brandon’s kookily sad sister, Sissy, is so white that she is played by Carey Mulligan, and is called Sissy. His apartment, in what might be seen as a reflection of his inner turmoil, is white and expensive, but lit so that above all else, it looks blue.)

It occurred to me, when thinking about Ronnie’s bathroom scene, that this is not McQueen’s first time depicting the repressed, deep-seated trauma of a wealthy but unhappy individual on film: that Shame, whose central character appeared to have developed sex-addiction in the wake of some unspecified, formative trauma—maybe psychic, maybe physical—addressed a similar, if not entirely symmetrical, ache. The sex addict, Brandon, as played in the key of Patrick Bateman by the Irish actor Michael Fassbender, also contained his introspection and his self-injurious anger within the confines of the bathroom. Often, his releases there were masturbatory. So, on some level, was the movie; lacking detailed and elucidating background information, Brandon’s tragedy became the tragedy of a successful, very handsome white man tortured by the need to regularly have sex with one or more women who resemble fashion models. (Brandon’s kookily sad sister, Sissy, is so white that she is played by Carey Mulligan, and is called Sissy. His apartment, in what might be seen as a reflection of his inner turmoil, is white and expensive, but lit so that above all else, it looks blue.)

If we were to stop and ask ourselves how our lives might be improved, one likely answer that might occur to us is that we should spend less time at work. At least that is what the statistics suggest.

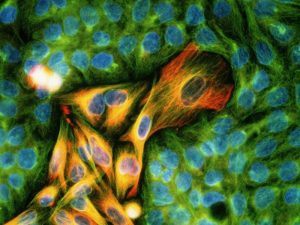

If we were to stop and ask ourselves how our lives might be improved, one likely answer that might occur to us is that we should spend less time at work. At least that is what the statistics suggest. Cancer has an insidious talent for evading the natural defenses that should destroy it. What if we could find ways to help the immune system fight back? It has begun to happen. The growing field of immunotherapy is profoundly changing cancer treatment and has rescued many people with advanced malignancies that not long ago would have been a death sentence. “Patients with advanced cancer are increasingly living for years not months,” a

Cancer has an insidious talent for evading the natural defenses that should destroy it. What if we could find ways to help the immune system fight back? It has begun to happen. The growing field of immunotherapy is profoundly changing cancer treatment and has rescued many people with advanced malignancies that not long ago would have been a death sentence. “Patients with advanced cancer are increasingly living for years not months,” a