David Cyranoski in Nature:

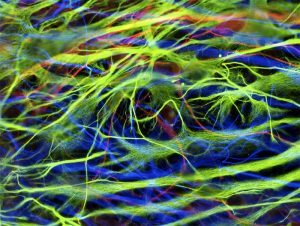

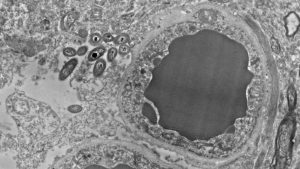

Japanese neurosurgeons have implanted ‘reprogrammed’ stem cells into the brain of a patient with Parkinson’s disease for the first time. The condition is only the second for which a therapy has been trialled using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which are developed by reprogramming the cells of body tissues such as skin so that they revert to an embryonic-like state, from which they can morph into other cell types. Scientists at Kyoto University use the technique to transform iPS cells into precursors to the neurons that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine. A shortage of neurons producing dopamine in people with Parkinson’s disease can lead to tremors and difficulty walking.

Japanese neurosurgeons have implanted ‘reprogrammed’ stem cells into the brain of a patient with Parkinson’s disease for the first time. The condition is only the second for which a therapy has been trialled using induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which are developed by reprogramming the cells of body tissues such as skin so that they revert to an embryonic-like state, from which they can morph into other cell types. Scientists at Kyoto University use the technique to transform iPS cells into precursors to the neurons that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine. A shortage of neurons producing dopamine in people with Parkinson’s disease can lead to tremors and difficulty walking.

In October, neurosurgeon Takayuki Kikuchi at Kyoto University Hospital implanted 2.4 million dopamine precursor cells into the brain of a patient in his 50s. In the three-hour procedure, Kikuchi’s team deposited the cells into 12 sites, known to be centres of dopamine activity. Dopamine precursor cells have been shown to improve symptoms of Parkinson’s disease in monkeys. Stem-cell scientist Jun Takahashi and colleagues at Kyoto University derived the dopamine precursor cells from a stock of IPS cells stored at the university. These were developed by reprogramming skin cells taken from an anonymous donor. “The patient is doing well and there have been no major adverse reactions so far,” says Takahashi. The team will observe him for six months and, if no complications arise, will implant another 2.4 million dopamine precursor cells into his brain. The team plans to treat six more patients with Parkinson’s disease to test the technique’s safety and efficacy by the end of 2020.

More here.

Seven years since the heady days of

Seven years since the heady days of  In

In  For millions of soldiers, the

For millions of soldiers, the  Scholars have built a tight historical and corresponding conceptual link between the advent of the rectangular, Renaissance frame and the advent of linear perspective. It’s true that the renovation of Fra Angelico’s San Domenico altarpiece entailed both, but this was usually not the case. In 1480, about a century and a half after it was made, Giotto’s altarpiece for the Baroncelli Chapel in Santa Croce was renovated. Its original frame was removed and discarded, along with God the Father, who had occupied the gable above the heads of the Virgin and Christ. Spandrels decorated with vermilion cherubim were added, along with a new, rectangular frame that slices right through the curves of the cusped arches.

Scholars have built a tight historical and corresponding conceptual link between the advent of the rectangular, Renaissance frame and the advent of linear perspective. It’s true that the renovation of Fra Angelico’s San Domenico altarpiece entailed both, but this was usually not the case. In 1480, about a century and a half after it was made, Giotto’s altarpiece for the Baroncelli Chapel in Santa Croce was renovated. Its original frame was removed and discarded, along with God the Father, who had occupied the gable above the heads of the Virgin and Christ. Spandrels decorated with vermilion cherubim were added, along with a new, rectangular frame that slices right through the curves of the cusped arches. ‘A dragon is no idle fancy,’ wrote Tolkien in 1936, but ‘a potent creation of men’s imagination, richer in significance than his barrow is in gold’. The potency has only increased over the last eighty years. Dragons crowd the pages of modern fantasy; no one needs telling that Daenerys, the Mother of Dragons, holds a crucial place in George R R Martin’s Game of Thrones universe.

‘A dragon is no idle fancy,’ wrote Tolkien in 1936, but ‘a potent creation of men’s imagination, richer in significance than his barrow is in gold’. The potency has only increased over the last eighty years. Dragons crowd the pages of modern fantasy; no one needs telling that Daenerys, the Mother of Dragons, holds a crucial place in George R R Martin’s Game of Thrones universe. Although it was Klimt’s paintings that first impressed Schiele, especially a solo show in 1908, the two men didn’t meet until the following year when they established a strong rapport and exchanged drawings. The role of drawings occupied a different place in the art of each man. The majority of Klimt’s were composed with paintings in mind but he also made private works, often quickly executed, that deviated from the ideal of heady beauty that permeated his paintings. Sketches of his elderly mother or a nude pregnant woman past the first flush of youth shed stylisation for an unflinching intimacy. Sometimes he didn’t bother with limbs, while figures fill the sheet like columns, cropped at the head and feet. Schiele, though, took it all in.

Although it was Klimt’s paintings that first impressed Schiele, especially a solo show in 1908, the two men didn’t meet until the following year when they established a strong rapport and exchanged drawings. The role of drawings occupied a different place in the art of each man. The majority of Klimt’s were composed with paintings in mind but he also made private works, often quickly executed, that deviated from the ideal of heady beauty that permeated his paintings. Sketches of his elderly mother or a nude pregnant woman past the first flush of youth shed stylisation for an unflinching intimacy. Sometimes he didn’t bother with limbs, while figures fill the sheet like columns, cropped at the head and feet. Schiele, though, took it all in. On 24 July 1967, the poet Paul Celan gave a reading in Freiburg im Brisgau. At the time he was on a leave of absence from Saint-Anne psychiatric hospital, where he had been interned after suffering a nervous breakdown, in the midst of which he attempted suicide. At the reading was the philosopher Martin Heidegger. The day after the reading Celan was invited to a meeting with Heidegger at the philosopher’s hut. On arrival Celan signed the guestbook, then the two men went for a walk, which was curtailed by rain, and were driven back to the hut. After their brief meeting Celan returned to Saint-Anne’s. One week later, on 1 August, Celan wrote a poem about the encounter in the form of a single, oblique sentence named after the place where Heidegger’s hut stood, “Todtnauberg”. The title contained two words crucial to both the the poetry of Celan and the philosophy of Heidegger – berg meaning mountain, and todt, death.

On 24 July 1967, the poet Paul Celan gave a reading in Freiburg im Brisgau. At the time he was on a leave of absence from Saint-Anne psychiatric hospital, where he had been interned after suffering a nervous breakdown, in the midst of which he attempted suicide. At the reading was the philosopher Martin Heidegger. The day after the reading Celan was invited to a meeting with Heidegger at the philosopher’s hut. On arrival Celan signed the guestbook, then the two men went for a walk, which was curtailed by rain, and were driven back to the hut. After their brief meeting Celan returned to Saint-Anne’s. One week later, on 1 August, Celan wrote a poem about the encounter in the form of a single, oblique sentence named after the place where Heidegger’s hut stood, “Todtnauberg”. The title contained two words crucial to both the the poetry of Celan and the philosophy of Heidegger – berg meaning mountain, and todt, death.

This past Sunday, November 11, marked the Centennial of Armistice Day, the European commemoration of the agreement to end World War I. Representatives from more than 60 countries attended carefully choreographed ceremonies to honor the sacrifice of those who fought.

This past Sunday, November 11, marked the Centennial of Armistice Day, the European commemoration of the agreement to end World War I. Representatives from more than 60 countries attended carefully choreographed ceremonies to honor the sacrifice of those who fought.

In a recent study, data scientists based in Japan found that classical music over the past several centuries has followed laws of evolution. How can non-living cultural expression adhere to these rules?

In a recent study, data scientists based in Japan found that classical music over the past several centuries has followed laws of evolution. How can non-living cultural expression adhere to these rules?

The crocodiles know. They form pincers on either side of the crossing point. Richard says they feel the vibration of all those hooves along the riverbank above them.

The crocodiles know. They form pincers on either side of the crossing point. Richard says they feel the vibration of all those hooves along the riverbank above them.