Rajagoalan and Long in Nature:

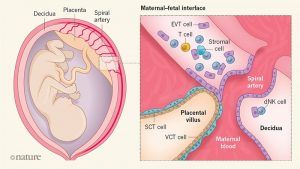

Scientists have long puzzled over the ‘immunological paradox’ of pregnancy1: how does the mother tolerate the fetus — a foreign entity that carries some of the father’s DNA? In a paper in Nature, Vento-Tormo et al.2 investigate this enigma. The authors performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) of cells isolated from the placenta and the decidua (the lining of the pregnant uterus), and from matching maternal blood for comparison. They identified an array of cell types unique to this maternal–fetal interface, and inferred the existence of a large network of potential interactions between them that would favour immunological tolerance and nurture the growth of the fetus. The authors’ molecular atlas provides an impressive resource for future studies of pregnancy and its complications.

Scientists have long puzzled over the ‘immunological paradox’ of pregnancy1: how does the mother tolerate the fetus — a foreign entity that carries some of the father’s DNA? In a paper in Nature, Vento-Tormo et al.2 investigate this enigma. The authors performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) of cells isolated from the placenta and the decidua (the lining of the pregnant uterus), and from matching maternal blood for comparison. They identified an array of cell types unique to this maternal–fetal interface, and inferred the existence of a large network of potential interactions between them that would favour immunological tolerance and nurture the growth of the fetus. The authors’ molecular atlas provides an impressive resource for future studies of pregnancy and its complications.

The early embryo develops into a structure called the blastocyst, which implants in the lining of the uterus. Implantation triggers the development of the placenta from fetal membranes. The placenta nourishes the fetus through the umbilical cord3. Abnormal placental development can lead to several complications of pregnancy, including pre-eclampsia, fetal growth restriction and stillbirth. A better understanding of human placental development is sorely needed, but there is no good animal model for this process — it has to be studied in women. Vento-Tormo et al. collected placental, decidual and blood samples from pregnancies that had been electively terminated at between 6 and 14 weeks of gestation. The authors’ scRNAseq analysis enabled them to distinguish between cells of maternal and fetal origin, because the latter include RNA sequences that are absent in the mother. This clearly revealed that cells from the fetus had migrated into the maternal decidua (Fig. 1), and that a small subset of maternal immune cells called macrophages were located in the placenta.

More here.

For educated liberals, Jill Lepore is perhaps the most prominent historian in America today. Since 2005, two years after she moved across the Charles River from Boston University to Harvard, Lepore has written dozens of reviews and essays for the New Yorker on everything from Thomas Paine and Kit Carson to Wonder Woman and Rachel Carson. In some ways, this was a surprising development. When Lepore started her career in the Nineties, she specialized in colonial history, a period that many people view as equal parts boring and confusing. Lepore is, however, a gifted researcher and a lively writer, and her early books rightfully garnered acclaim: the first won the Bancroft Prize, and another was a finalist for the Pulitzer.

For educated liberals, Jill Lepore is perhaps the most prominent historian in America today. Since 2005, two years after she moved across the Charles River from Boston University to Harvard, Lepore has written dozens of reviews and essays for the New Yorker on everything from Thomas Paine and Kit Carson to Wonder Woman and Rachel Carson. In some ways, this was a surprising development. When Lepore started her career in the Nineties, she specialized in colonial history, a period that many people view as equal parts boring and confusing. Lepore is, however, a gifted researcher and a lively writer, and her early books rightfully garnered acclaim: the first won the Bancroft Prize, and another was a finalist for the Pulitzer. In just a few weeks, humanity may take its first paid ride into the age of driverless cars.

In just a few weeks, humanity may take its first paid ride into the age of driverless cars. Entrepreneur Andrew Yang has a big goal for a relatively unknown business person: to reach the White House. And he’s aiming to get there by selling America on the idea that all citizens, ages 18-64, should get a check for

Entrepreneur Andrew Yang has a big goal for a relatively unknown business person: to reach the White House. And he’s aiming to get there by selling America on the idea that all citizens, ages 18-64, should get a check for  Mitchell settled in the imaginations of pop listeners in the early 70s. In the UK, “Big Yellow Taxi” was a biggish hit in the summer of 1970, its glassily sardonic reflections upon humanity’s relationship with the environment marking out the flaxen-haired Scando-Canadian hippie-chick who sang it as a poster girl for a certain kind of wholesome big-R Romanticism. She was fey, frowning, Nordically bony, the perfect package for the deal: a one-take archetype. What the songs didn’t articulate and the voice didn’t swoop upon like a slender bird, the hair flowed over in a river of molten gold. Like nature busily abhorring a vacuum, Mitchell flooded space that ought perhaps to have been filled by an array of other women before her: the role of thoughtful, poetically articulate, unsentimental, insubordinate, self-expressive female countercultural pop icon. It was a tough job and maybe Mitchell didn’t ask for it, but she certainly got it and then did it with never less than questioning commitment.

Mitchell settled in the imaginations of pop listeners in the early 70s. In the UK, “Big Yellow Taxi” was a biggish hit in the summer of 1970, its glassily sardonic reflections upon humanity’s relationship with the environment marking out the flaxen-haired Scando-Canadian hippie-chick who sang it as a poster girl for a certain kind of wholesome big-R Romanticism. She was fey, frowning, Nordically bony, the perfect package for the deal: a one-take archetype. What the songs didn’t articulate and the voice didn’t swoop upon like a slender bird, the hair flowed over in a river of molten gold. Like nature busily abhorring a vacuum, Mitchell flooded space that ought perhaps to have been filled by an array of other women before her: the role of thoughtful, poetically articulate, unsentimental, insubordinate, self-expressive female countercultural pop icon. It was a tough job and maybe Mitchell didn’t ask for it, but she certainly got it and then did it with never less than questioning commitment. In 1962 Derrida published a book-length introduction to his translation of Husserl’s short work The Origin of Geometry in which the seeds of his later thinking were already evident, but it was in 1967 that he truly made his mark on the French philosophical scene. In that year he published no fewer than three books, and in so doing displayed the startling originality and productiveness that was to characterize his career until his death from pancreatic cancer in 2004: L’écriture et la difference, La voix et le phénomène and De la grammatologie. Five years later, another trio of books appeared, cementing Derrida’s position at the forefront of what became known in the English-speaking world as “post-structuralism”: La Dissemination, Marges de la philosophie and Positions. There followed a steady stream of publications; a recent posthumous volume produced by his favourite French publisher, Galilée, lists fifty-seven books from their own house and another thirty-one from other publishers – and this list includes only the first two volumes in the planned series of hitherto unpublished seminars delivered over more than forty years.

In 1962 Derrida published a book-length introduction to his translation of Husserl’s short work The Origin of Geometry in which the seeds of his later thinking were already evident, but it was in 1967 that he truly made his mark on the French philosophical scene. In that year he published no fewer than three books, and in so doing displayed the startling originality and productiveness that was to characterize his career until his death from pancreatic cancer in 2004: L’écriture et la difference, La voix et le phénomène and De la grammatologie. Five years later, another trio of books appeared, cementing Derrida’s position at the forefront of what became known in the English-speaking world as “post-structuralism”: La Dissemination, Marges de la philosophie and Positions. There followed a steady stream of publications; a recent posthumous volume produced by his favourite French publisher, Galilée, lists fifty-seven books from their own house and another thirty-one from other publishers – and this list includes only the first two volumes in the planned series of hitherto unpublished seminars delivered over more than forty years.

Many people are familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, in which he argued that basic needs such as safety, belonging, and self-esteem must be satisfied (to a reasonable healthy degree) before being able to fully realize one’s unique creative and humanitarian potential. What many people may not realize is that a strict hierarchy was not really the focus of his work (and in fact,

Many people are familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, in which he argued that basic needs such as safety, belonging, and self-esteem must be satisfied (to a reasonable healthy degree) before being able to fully realize one’s unique creative and humanitarian potential. What many people may not realize is that a strict hierarchy was not really the focus of his work (and in fact,

In cosmological or Darwinian terms, a millennium is but an instant. So let us fast forward not for a few centuries or millennia, but for an astronomical timescale millions of times longer than that. The stellar births and deaths in our galaxy will gradually proceed more slowly, until jolted by the environmental shock of an impact with the Andromeda Galaxy, maybe four billion years hence. The debris of our galaxy, Andromeda and their smaller companions—which now make up what is called the Local Group—will thereafter aggregate into one amorphous swarm of stars. Many billions of years after that, gravitational attraction will be overwhelmed by a mysterious force latent in empty space that pushes galaxies apart from each other. Galaxies accelerate away and disappear over a horizon. All that will be left in view, after 100bn years, will be the dead and dying stars of our Local Group, which could continue for trillions of years. Against the darkening background, sub-atomic particles such as protons may decay, dark matter particles annihilate and black holes evaporate—and then silence.

In cosmological or Darwinian terms, a millennium is but an instant. So let us fast forward not for a few centuries or millennia, but for an astronomical timescale millions of times longer than that. The stellar births and deaths in our galaxy will gradually proceed more slowly, until jolted by the environmental shock of an impact with the Andromeda Galaxy, maybe four billion years hence. The debris of our galaxy, Andromeda and their smaller companions—which now make up what is called the Local Group—will thereafter aggregate into one amorphous swarm of stars. Many billions of years after that, gravitational attraction will be overwhelmed by a mysterious force latent in empty space that pushes galaxies apart from each other. Galaxies accelerate away and disappear over a horizon. All that will be left in view, after 100bn years, will be the dead and dying stars of our Local Group, which could continue for trillions of years. Against the darkening background, sub-atomic particles such as protons may decay, dark matter particles annihilate and black holes evaporate—and then silence. Plastic is everywhere, and suddenly we have decided that is a very bad thing. Until recently, plastic enjoyed a sort of anonymity in ubiquity: we were so thoroughly surrounded that we hardly noticed it. You might be surprised to learn, for instance, that today’s cars and planes are, by volume, about 50% plastic. More clothing is made out of polyester and nylon, both plastics, than cotton or wool. Plastic is also used in minute quantities as an adhesive to seal the vast majority of the 60bn teabags used in Britain each year.

Plastic is everywhere, and suddenly we have decided that is a very bad thing. Until recently, plastic enjoyed a sort of anonymity in ubiquity: we were so thoroughly surrounded that we hardly noticed it. You might be surprised to learn, for instance, that today’s cars and planes are, by volume, about 50% plastic. More clothing is made out of polyester and nylon, both plastics, than cotton or wool. Plastic is also used in minute quantities as an adhesive to seal the vast majority of the 60bn teabags used in Britain each year. One evening this fall at a house in West Hollywood,

One evening this fall at a house in West Hollywood, Derek Mahon’s new volume of poems, Against the Clock, again proves him one of the greatest contemporary masters of poetic form. Preoccupied as he is with his advancing age and the “final deadline” looming in the future, the suppleness and subtleness of his flexible rhythms and rhymes keep the subject from becoming ponderous. Mahon knows all about the dark side of life, but has an extraordinary ability to set his style against it, as it were, so that his formal ingenuity provides a counterweight. It would be false to say that the darkness is vanquished ‑ it is not. A Mahon poem does not engage in illusionary antics or light-headed optimism. It knows the type of world in which it must reside. But its own energy carries it through with panache: “life is short and time, the great reminder, / closes the file of new poems in line / for the printer and binder” ‑ and these lines in parenthesis no less. Rhymes as unusual as “reminder” and “binder” abound in this volume, and display one of Mahon’s greatest talents: his ability to take so-called traditional forms and subject them to change and play. At this point in his career it seems effortless. His play with the units of poetic form is creative to the point of ingenuity ‑ but not quite, since Mahon sets himself against ingenuity for its own sake, or wordplay that is not anchored by deep feeling. And yet “play” is the right word for what this serious poet allows himself to do, and perhaps must do.

Derek Mahon’s new volume of poems, Against the Clock, again proves him one of the greatest contemporary masters of poetic form. Preoccupied as he is with his advancing age and the “final deadline” looming in the future, the suppleness and subtleness of his flexible rhythms and rhymes keep the subject from becoming ponderous. Mahon knows all about the dark side of life, but has an extraordinary ability to set his style against it, as it were, so that his formal ingenuity provides a counterweight. It would be false to say that the darkness is vanquished ‑ it is not. A Mahon poem does not engage in illusionary antics or light-headed optimism. It knows the type of world in which it must reside. But its own energy carries it through with panache: “life is short and time, the great reminder, / closes the file of new poems in line / for the printer and binder” ‑ and these lines in parenthesis no less. Rhymes as unusual as “reminder” and “binder” abound in this volume, and display one of Mahon’s greatest talents: his ability to take so-called traditional forms and subject them to change and play. At this point in his career it seems effortless. His play with the units of poetic form is creative to the point of ingenuity ‑ but not quite, since Mahon sets himself against ingenuity for its own sake, or wordplay that is not anchored by deep feeling. And yet “play” is the right word for what this serious poet allows himself to do, and perhaps must do. “Every poet is an optimist,” Baldwin

“Every poet is an optimist,” Baldwin  ‘Like

‘Like  At Wayne State University, a commuter campus in Detroit where faculty members and students struggle to turn people out for events, the

At Wayne State University, a commuter campus in Detroit where faculty members and students struggle to turn people out for events, the