Katy Guest in The Guardian:

It can be reassuring to reassess life by taking a long view. In this book about “how the Earth made us”, Lewis Dartnell considers the last billion or so years, in his mission to understand how our planet has been “a leading protagonist in the story of humanity”. Our human bodies are, inevitably, made from the elements of Earth: our blood, sweat and tears come from the rocky fabric of its crust; our hair is made from volcanic debris. But Dartnell also explains how humanity became early civilisation and then the societies we live in now: how the formation of the Channel, through megaflooding events hundreds of thousands of years ago, “has had profound ramifications through history for Britain”; how Labour votes have followed coal seams laid down in the Carboniferous period. Never has geological history seemed so current.

It can be reassuring to reassess life by taking a long view. In this book about “how the Earth made us”, Lewis Dartnell considers the last billion or so years, in his mission to understand how our planet has been “a leading protagonist in the story of humanity”. Our human bodies are, inevitably, made from the elements of Earth: our blood, sweat and tears come from the rocky fabric of its crust; our hair is made from volcanic debris. But Dartnell also explains how humanity became early civilisation and then the societies we live in now: how the formation of the Channel, through megaflooding events hundreds of thousands of years ago, “has had profound ramifications through history for Britain”; how Labour votes have followed coal seams laid down in the Carboniferous period. Never has geological history seemed so current.

To cut a (very) long story short, we are the result of plate tectonics and ice ages. The crashing together of continents caused the cooling and drying of Earth, which enabled the growth of the grasses that form the basis of our diet, and humans to walk across the land out of Africa. The rocky hills of Greece demanded foot soldiers to fight battles there, each of whom had a say in events, helping to create democracy. A fascinating chapter explains trade winds, the age of exploration, colonisation and the “subsequent history of our world”. Dartnell is an eloquent, conversational guide to these daunting aeons of time. He writes of land masses swelling and bursting “like a huge zit”, and global warming “triggered by a great methane flatulence of the oceans”. And it is always useful to think about chronology. “Cleopatra lived closer in time to the modern world of iPhones,” he writes, “than she did to the ancient construction of the Great Pyramid at Giza.”

More here.

Does the language you speak influence how you think? This is the question behind the famous

Does the language you speak influence how you think? This is the question behind the famous  By 2014, many Americans had forgotten about New Atheism. For liberal Americans in the depths of the Bush years, anti-religious best sellers by Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens came as—for lack of a better word—a godsend. With the Christian right in the White House, and jihadist terrorism perceived to be a constant danger in the wake of 9/11, a vocal rationalist atheism appeared to many a natural and necessary counterweight. But after nearly six years of Barack Obama’s presidency, Bush and his born-again gang were far from the high seats of power, the War on Terror was no longer a feature of most people’s daily lives, and there was a widespread impression of leftward progress on social issues. The services of the anti-religious crusaders were no longer needed.

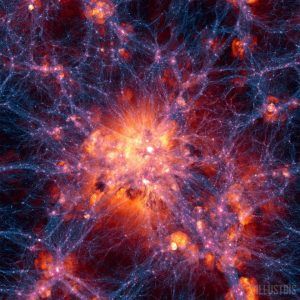

By 2014, many Americans had forgotten about New Atheism. For liberal Americans in the depths of the Bush years, anti-religious best sellers by Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens came as—for lack of a better word—a godsend. With the Christian right in the White House, and jihadist terrorism perceived to be a constant danger in the wake of 9/11, a vocal rationalist atheism appeared to many a natural and necessary counterweight. But after nearly six years of Barack Obama’s presidency, Bush and his born-again gang were far from the high seats of power, the War on Terror was no longer a feature of most people’s daily lives, and there was a widespread impression of leftward progress on social issues. The services of the anti-religious crusaders were no longer needed. One of the greatest puzzles in the entire Universe is the dark matter mystery. In theory, for every bit of normal matter (like us) in the Universe, there should be approximately five times as much dark matter. Both normal and dark matter should experience gravitation equally, meaning that the largest structures in the Universe — galaxies, clusters of galaxies, and cosmic filaments — should contain and be dominated by dark matter. When we measure the motions of individual galaxies, both isolated and in clusters, the normal matter alone is not enough to explain what we see. Dark matter is also required.

One of the greatest puzzles in the entire Universe is the dark matter mystery. In theory, for every bit of normal matter (like us) in the Universe, there should be approximately five times as much dark matter. Both normal and dark matter should experience gravitation equally, meaning that the largest structures in the Universe — galaxies, clusters of galaxies, and cosmic filaments — should contain and be dominated by dark matter. When we measure the motions of individual galaxies, both isolated and in clusters, the normal matter alone is not enough to explain what we see. Dark matter is also required. So, there you are, having worked your way through a crowd denser than a Brexit negotiation, standing in front of your prize. The Mona Lisa in the Louvre. What do you do? Look more closely at that enigmatic smile? Wonder at the subtle gradations of light and shadow in Leonardo’s rendering of the face? Admire the illusion of depth?

So, there you are, having worked your way through a crowd denser than a Brexit negotiation, standing in front of your prize. The Mona Lisa in the Louvre. What do you do? Look more closely at that enigmatic smile? Wonder at the subtle gradations of light and shadow in Leonardo’s rendering of the face? Admire the illusion of depth? Sometimes my experiences with the Postal Service are almost enough to turn me into a right-wing libertarian. For instance: They offer a special discounted rate for sending magazines through the post. Which is good—I run a magazine that is sent through the post! In order to get the rate, however, you have to meticulously obey every single instruction in the 56 pages of

Sometimes my experiences with the Postal Service are almost enough to turn me into a right-wing libertarian. For instance: They offer a special discounted rate for sending magazines through the post. Which is good—I run a magazine that is sent through the post! In order to get the rate, however, you have to meticulously obey every single instruction in the 56 pages of  In his columns, Indiana skewered the art world’s bloated egos and grotesque superficiality, but he was interested, above all, in scrutinizing who held power and how it was deployed. In a particularly trenchant essay on Richard Serra’s lawsuit against the General Services Administration—the government agency that had commissioned his 1981 public sculpture Tilted Arc for the plaza outside the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in Manhattan and, at the urging of the people who worked there, now planned to remove it against the artist’s wishes—Indiana chides Serra and his defenders for their naivete: “Who on earth did these people think they were dealing with in the first place?” he asks. “If you are so enamored of [power] that you regularly ornament its dinner tables, ride cackling through the night in its limousines, and sign worthless contracts with it, it is no problem of mine or anyone else’s if power decides, one bored afternoon, to add you to the menu instead of inviting you to eat.”

In his columns, Indiana skewered the art world’s bloated egos and grotesque superficiality, but he was interested, above all, in scrutinizing who held power and how it was deployed. In a particularly trenchant essay on Richard Serra’s lawsuit against the General Services Administration—the government agency that had commissioned his 1981 public sculpture Tilted Arc for the plaza outside the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in Manhattan and, at the urging of the people who worked there, now planned to remove it against the artist’s wishes—Indiana chides Serra and his defenders for their naivete: “Who on earth did these people think they were dealing with in the first place?” he asks. “If you are so enamored of [power] that you regularly ornament its dinner tables, ride cackling through the night in its limousines, and sign worthless contracts with it, it is no problem of mine or anyone else’s if power decides, one bored afternoon, to add you to the menu instead of inviting you to eat.” Omnipresent social media places a claim on our elapsed time, our fractured lives. We’re all sad in our very own way. As there are no lulls or quiet moments anymore, the result is fatigue, depletion and loss of energy. We’re becoming obsessed with waiting. How long have you been forgotten by your love ones? Time, meticulously measured on every app, tells us right to our face. Chronos hurts. Should I post something to attract attention and show I’m still here? Nobody likes me anymore. As the random messages keep relentlessly piling in, there’s no way to halt them, to take a moment and think it all through.

Omnipresent social media places a claim on our elapsed time, our fractured lives. We’re all sad in our very own way. As there are no lulls or quiet moments anymore, the result is fatigue, depletion and loss of energy. We’re becoming obsessed with waiting. How long have you been forgotten by your love ones? Time, meticulously measured on every app, tells us right to our face. Chronos hurts. Should I post something to attract attention and show I’m still here? Nobody likes me anymore. As the random messages keep relentlessly piling in, there’s no way to halt them, to take a moment and think it all through. The title of Ferruccio Busoni’s 1907 manifesto Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music might suggest that the Italian pianist-composer would be looking to the future, yet many of its philosophical passages find him lingering in the past. Writing out “of convictions long held and slowly matured” (he was 41 at the time), Busoni extolled the virtues of the Baroque and classical ages, Bach and Beethoven being the exemplars—in “spirit and emotion they will probably remain unexcelled.” Busoni’s embrace of the past, however, was no rejection of modernity. “Among both ‘modern’ and ‘old’ works,” he wrote, “we find good and bad, genuine and spurious. There is nothing properly modern—only things which have come into being earlier or later; longer in bloom, or sooner withered. The Modern and the Old have always been.” Past and present, tradition and experiment—all could happily coexist in art. Thus, in more or less the same breath, Busoni could praise the elegance of Mozartian classicism while pondering some avant-garde technique, such as microtonal harmony. What mattered most of all were spirit and emotion; “he who mounts to their uttermost heights,” the musician wrote, “will always tower above the crowd.”

The title of Ferruccio Busoni’s 1907 manifesto Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music might suggest that the Italian pianist-composer would be looking to the future, yet many of its philosophical passages find him lingering in the past. Writing out “of convictions long held and slowly matured” (he was 41 at the time), Busoni extolled the virtues of the Baroque and classical ages, Bach and Beethoven being the exemplars—in “spirit and emotion they will probably remain unexcelled.” Busoni’s embrace of the past, however, was no rejection of modernity. “Among both ‘modern’ and ‘old’ works,” he wrote, “we find good and bad, genuine and spurious. There is nothing properly modern—only things which have come into being earlier or later; longer in bloom, or sooner withered. The Modern and the Old have always been.” Past and present, tradition and experiment—all could happily coexist in art. Thus, in more or less the same breath, Busoni could praise the elegance of Mozartian classicism while pondering some avant-garde technique, such as microtonal harmony. What mattered most of all were spirit and emotion; “he who mounts to their uttermost heights,” the musician wrote, “will always tower above the crowd.” Neuroscientists have for the first time discovered differences between the ‘software’ of humans and monkey brains, using a technique that tracks single neurons. They found that human brains trade off ‘robustness’ — a measure of how synchronized neuron signals are — for greater efficiency in information processing. The researchers hypothesize that the results might help to explain humans’ unique intelligence, as well as their susceptibility to psychiatric disorders. The findings were published in Cell

Neuroscientists have for the first time discovered differences between the ‘software’ of humans and monkey brains, using a technique that tracks single neurons. They found that human brains trade off ‘robustness’ — a measure of how synchronized neuron signals are — for greater efficiency in information processing. The researchers hypothesize that the results might help to explain humans’ unique intelligence, as well as their susceptibility to psychiatric disorders. The findings were published in Cell

I wrote the first draft of this post on my typewriter. Like much of my other writing, this piece began as handwritten notes and drafts typed on a nice little portable typewriter, which is a little younger than I am and which I expect to use for the rest of my life.

I wrote the first draft of this post on my typewriter. Like much of my other writing, this piece began as handwritten notes and drafts typed on a nice little portable typewriter, which is a little younger than I am and which I expect to use for the rest of my life. Although we know bias and racism exists in most societies, when put into coherent terms in the form of research the impact is stark and exposes just how much a part of life racism is for so many people. Booth and Mohdin’s (The Guardian 2018) article ‘Revealed: the stark evidence of everyday bias in Britain’ setting out the findings of a poll on the levels of negative experience, more often associated with racism, by Black, Asian and minority and ethnic groups in the United Kingdom(UK) does just that. Thus, for example, from amongst its many findings the survey revealed that 43% of those from a minority background had been overlooked for work promotion in the last five years in comparison with only 18% of white people who reported the same experience. Likewise, 38% of people from ethnic minorities said they had been wrongly suspected of shop lifting in the last five years, in comparison with 14% of white people. Significantly, 53% of people from a minority background believed they had been treated differently because of their hair, clothes and appearance, in comparison with 29% of white people. In the work-place also 57% of minorities said they felt they had to work harder to succeed in Britain because of their ethnicity, and 40% said they earned less.

Although we know bias and racism exists in most societies, when put into coherent terms in the form of research the impact is stark and exposes just how much a part of life racism is for so many people. Booth and Mohdin’s (The Guardian 2018) article ‘Revealed: the stark evidence of everyday bias in Britain’ setting out the findings of a poll on the levels of negative experience, more often associated with racism, by Black, Asian and minority and ethnic groups in the United Kingdom(UK) does just that. Thus, for example, from amongst its many findings the survey revealed that 43% of those from a minority background had been overlooked for work promotion in the last five years in comparison with only 18% of white people who reported the same experience. Likewise, 38% of people from ethnic minorities said they had been wrongly suspected of shop lifting in the last five years, in comparison with 14% of white people. Significantly, 53% of people from a minority background believed they had been treated differently because of their hair, clothes and appearance, in comparison with 29% of white people. In the work-place also 57% of minorities said they felt they had to work harder to succeed in Britain because of their ethnicity, and 40% said they earned less. In the immortal words of Prince Rogers Nelson’s party gem from 1982:

In the immortal words of Prince Rogers Nelson’s party gem from 1982:

Simple questions often yield complex answers. For instance: what is the difference between a language and a dialect? If you ask this of a linguist, get comfortable. Despite the simplicity of the query, there are a lot of possible answers.

Simple questions often yield complex answers. For instance: what is the difference between a language and a dialect? If you ask this of a linguist, get comfortable. Despite the simplicity of the query, there are a lot of possible answers. If you can believe it, Japanese novelist, talking cat enthusiast, and weird ear chronicler Haruki Murakami turned 70 years old this weekend. 70! But I suppose we should believe it, despite the youthful gaiety and creative magic of his prose: the internationally bestselling writer has 14 novels and a handful of short stories under his belt, and it’s safe to say he’s one of the most famous contemporary writers in the world. To celebrate his birthday, and as a gift to those of you who hope to be the kind of writer Murakami is when you turn 70, I’ve collected some of his best writing advice below.

If you can believe it, Japanese novelist, talking cat enthusiast, and weird ear chronicler Haruki Murakami turned 70 years old this weekend. 70! But I suppose we should believe it, despite the youthful gaiety and creative magic of his prose: the internationally bestselling writer has 14 novels and a handful of short stories under his belt, and it’s safe to say he’s one of the most famous contemporary writers in the world. To celebrate his birthday, and as a gift to those of you who hope to be the kind of writer Murakami is when you turn 70, I’ve collected some of his best writing advice below.