Colin Dickey in The New Republic:

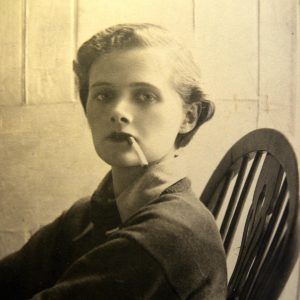

Every so often a book comes along and changes the way you see a classic of literature. The Diary of Virginia Woolf, published between 1977 and 1984, came out decades after Woolf’s death in 1941, and added a stunning lens through which to view her long and dynamic career. Her husband Leonard had carefully edited a volume initially in 1953, one that focused entirely on Woolf’s writing process and avoided personal details, but it was only when Woolf’s diaries were released in their totality that readers gained a precious glimpse inside a complicated mind at work.

Every so often a book comes along and changes the way you see a classic of literature. The Diary of Virginia Woolf, published between 1977 and 1984, came out decades after Woolf’s death in 1941, and added a stunning lens through which to view her long and dynamic career. Her husband Leonard had carefully edited a volume initially in 1953, one that focused entirely on Woolf’s writing process and avoided personal details, but it was only when Woolf’s diaries were released in their totality that readers gained a precious glimpse inside a complicated mind at work.

They revealed a Woolf unexpectedly playful and at times mundane: “So now I have assembled my facts,” she wrote on August 22, 1922, “to which I now add my spending 10/6 on photographs, which we developed in my dress cupboard last night; & they are all failures. Compliments, clothes, building, photography—it is for these reasons that I cannot write Mrs Dalloway.” They also reveal a Woolf at times both vicious and shitty: her cattiness, her casual racism. Ruth Gruber, who wrote the first PhD dissertation on Woolf, had a short, pleasant correspondence with her in the 1930s, only to discover, when the diaries were later published, Woolf referring to her dismissively as a “German Jewess” (Gruber was born in Brooklyn). As Gruber would write of the experience, “Diaries can rip the masks from their creators.”

Unlike many writers’ diaries, The Diary of Virginia Woolf has become more than just a gloss on her novels; it is a work of literature in and of itself, a powerful and startling look into the inner life of a woman writer during a dramatic time. “I will not be ‘famous,’ ‘great,’” she wrote in 1933. “I will go on adventuring, changing, opening my mind and my eyes, refusing to be stamped and stereotyped. The thing is to free one’s self: to let it find its dimensions, not be impeded.” Woolf began writing in a diary in 1897, when she was just 14 years old; she would continue on and off again, for the rest of her life; she would write the final entry four days before her death in March 1941. In total, she wrote over 770,000 words in her diaries alone.

More here.

When Lake Xochimilco near Mexico City was Lake Texcoco, and the Aztecs founded their island capital city of Tenochtitlan in 1325, a large aquatic salamander thrived in the surrounding lake. The

When Lake Xochimilco near Mexico City was Lake Texcoco, and the Aztecs founded their island capital city of Tenochtitlan in 1325, a large aquatic salamander thrived in the surrounding lake. The  Every so often a book comes along and changes the way you see a classic of literature. The Diary of Virginia Woolf, published between 1977 and 1984, came out decades after Woolf’s death in 1941, and added a stunning lens through which to view her long and dynamic career. Her husband Leonard had carefully edited a volume initially in 1953, one that focused entirely on Woolf’s writing process and avoided personal details, but it was only when Woolf’s diaries were released in their totality that readers gained a precious glimpse inside a complicated mind at work.

Every so often a book comes along and changes the way you see a classic of literature. The Diary of Virginia Woolf, published between 1977 and 1984, came out decades after Woolf’s death in 1941, and added a stunning lens through which to view her long and dynamic career. Her husband Leonard had carefully edited a volume initially in 1953, one that focused entirely on Woolf’s writing process and avoided personal details, but it was only when Woolf’s diaries were released in their totality that readers gained a precious glimpse inside a complicated mind at work.

Rationality has long been an important concept in the study of judgement and decision making. The highly

Rationality has long been an important concept in the study of judgement and decision making. The highly  Discussions about the state of democracy are suddenly all the rage. And it’s not hard to see why: Bolsonaro in Brazil, Trump in the US, Erdoğan in Turkey, Orbán in Hungary — all point to a resurgent authoritarianism and a diminution of democratic forms. But we can’t understand the current retrenchment without understanding how mass democracy came about in the first place.

Discussions about the state of democracy are suddenly all the rage. And it’s not hard to see why: Bolsonaro in Brazil, Trump in the US, Erdoğan in Turkey, Orbán in Hungary — all point to a resurgent authoritarianism and a diminution of democratic forms. But we can’t understand the current retrenchment without understanding how mass democracy came about in the first place. Sally Wen Mao’s new book of poems, “

Sally Wen Mao’s new book of poems, “ I

I The beating heart of it all, Du Maurier’s estate Menabilly, remains a secret few have been allowed to penetrate. Nestled behind locked gates, a visitor would find it impossible to catch even a glimpse of its infamous facade from the roadside. Nearby is the town of Fowey. Another great love. Once referred to as Du Maurier’s ‘salvation’, it is the picture of gentle tranquillity. By a twinkling blue estuary lined with quaint white cottages, you can glance at her other famous home —Ferryside. The coves are full of families, the beaches always busy. Journey on for forty minutes more, and you might stumble across the infamous Jamaica Inn. Far from an isolated hub of menacing activity and excitement, it now stands on a busy motorway leading out of Cornwall — an impersonal, family stop on the way back from a typical summer road trip.

The beating heart of it all, Du Maurier’s estate Menabilly, remains a secret few have been allowed to penetrate. Nestled behind locked gates, a visitor would find it impossible to catch even a glimpse of its infamous facade from the roadside. Nearby is the town of Fowey. Another great love. Once referred to as Du Maurier’s ‘salvation’, it is the picture of gentle tranquillity. By a twinkling blue estuary lined with quaint white cottages, you can glance at her other famous home —Ferryside. The coves are full of families, the beaches always busy. Journey on for forty minutes more, and you might stumble across the infamous Jamaica Inn. Far from an isolated hub of menacing activity and excitement, it now stands on a busy motorway leading out of Cornwall — an impersonal, family stop on the way back from a typical summer road trip. 2018 was a year overstuffed with culture. That’s just the way it is now, movies and TV and songs and memes and thoughtful features and endless, endless politics scrolling past our weary eyes at the speed of silicon and too-blue light. But in all the chaos there’s a moment where my hazy memories of frenetic consumption pause, for a piece of filmmaking that called on me to think hard and to remember. That movie was Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman.” It’s currently raking in a modest haul of awards, but for me, it’s going to linger long past the last bottle of popped January 1st champagne, a remarkable slice of light to which I’ll return for years to come.

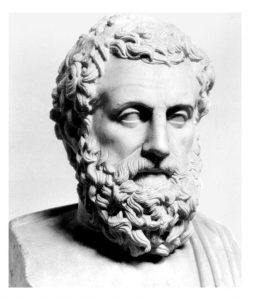

2018 was a year overstuffed with culture. That’s just the way it is now, movies and TV and songs and memes and thoughtful features and endless, endless politics scrolling past our weary eyes at the speed of silicon and too-blue light. But in all the chaos there’s a moment where my hazy memories of frenetic consumption pause, for a piece of filmmaking that called on me to think hard and to remember. That movie was Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman.” It’s currently raking in a modest haul of awards, but for me, it’s going to linger long past the last bottle of popped January 1st champagne, a remarkable slice of light to which I’ll return for years to come. Three years ago, New Year’s came and I promised to eat only organic. I lasted two weeks. A year ago, I resolved to run before dawn and take a cold shower every morning. That lasted two days. This year, I don’t have a resolution. Instead I read Edith Hall’s “Aristotle’s Way: How Ancient Wisdom Can Change Your Life,” and concluded I probably didn’t have to undergo some painful — and therefore temporary — transformation to remake my life. I just had to put some sustained effort into being properly happy.

Three years ago, New Year’s came and I promised to eat only organic. I lasted two weeks. A year ago, I resolved to run before dawn and take a cold shower every morning. That lasted two days. This year, I don’t have a resolution. Instead I read Edith Hall’s “Aristotle’s Way: How Ancient Wisdom Can Change Your Life,” and concluded I probably didn’t have to undergo some painful — and therefore temporary — transformation to remake my life. I just had to put some sustained effort into being properly happy. 1. My mother once saw the chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs; in Irish: “Rí Rua”) take a shit on Grafton Street and she scolded him. He just kept repeating his distinctive call “pink, pink, pink, trup,” over and over again, but you could kinda tell that he was mortified. Good bird, really; had trouble later with the auld drugs, and got very stout. Died way too young. In the eighties, those birds had a string of great hits.

1. My mother once saw the chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs; in Irish: “Rí Rua”) take a shit on Grafton Street and she scolded him. He just kept repeating his distinctive call “pink, pink, pink, trup,” over and over again, but you could kinda tell that he was mortified. Good bird, really; had trouble later with the auld drugs, and got very stout. Died way too young. In the eighties, those birds had a string of great hits. The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest particle accelerator. It’s a 16-mile-long underground ring, located at CERN in Geneva, in which protons collide at almost the speed of light.

The Large Hadron Collider is the world’s largest particle accelerator. It’s a 16-mile-long underground ring, located at CERN in Geneva, in which protons collide at almost the speed of light.  Michael Peppiatt’s memoir is subtitled Paris Among the Artists, but it could be called A Portrait of the Art Critic As an Older Man. Peppiatt, who is best known for his biography and memoirs of his friend

Michael Peppiatt’s memoir is subtitled Paris Among the Artists, but it could be called A Portrait of the Art Critic As an Older Man. Peppiatt, who is best known for his biography and memoirs of his friend  The word strike seems to be on everyone’s lips these days. Workers across the world have been striking to protest poor working conditions, to

The word strike seems to be on everyone’s lips these days. Workers across the world have been striking to protest poor working conditions, to  HOW LONG did an hour feel in 1971? Was it like three 2018 hours? Ten minutes? The music of the eighty-six-year-old French composer Éliane Radigue forces these questions because as much as it’s about synthesizers and magnetic tape and silence and held notes and resonance, it is also about time. Her work cannot be excerpted or sliced into representative swatches or versified. The movement from a piece’s beginning to its end is the motif itself; to lose even a little of that adventure is to lose the music. Œuvres électroniques (Electronic Works), a new fourteen-CD box set recently released by Ina GRM, collects pieces recorded between 1971 and 2007. The shortest of them is a little over seventeen minutes long; most of them run closer to an hour. These days, Radigue composes largely for acoustic stringed instruments, but she remains as focused an artist as electronic music has ever had, possibly because she never needed the equipment to hear her sound, only a series of tools with which to render it.

HOW LONG did an hour feel in 1971? Was it like three 2018 hours? Ten minutes? The music of the eighty-six-year-old French composer Éliane Radigue forces these questions because as much as it’s about synthesizers and magnetic tape and silence and held notes and resonance, it is also about time. Her work cannot be excerpted or sliced into representative swatches or versified. The movement from a piece’s beginning to its end is the motif itself; to lose even a little of that adventure is to lose the music. Œuvres électroniques (Electronic Works), a new fourteen-CD box set recently released by Ina GRM, collects pieces recorded between 1971 and 2007. The shortest of them is a little over seventeen minutes long; most of them run closer to an hour. These days, Radigue composes largely for acoustic stringed instruments, but she remains as focused an artist as electronic music has ever had, possibly because she never needed the equipment to hear her sound, only a series of tools with which to render it.