Quinn Slobodian in Boston Review:

In 2013 Charles Murray traveled to the Galápagos Islands to deliver an address to the Mont Pelerin Society—that font of neoliberalism, founded in 1947 by Friedrich Hayek. But Murray’s talk didn’t run through the usual neoliberal script: economic liberty, free trade, the genius of the entrepreneur. Instead, his subject was “the rediscovery of human nature and human diversity.” New discoveries in genetics, he argued, would induce “reversions to age-old understandings about the human animal” and undo “the intellectual eclipse of human nature and human diversity in the United States.” He welcomed these developments not only to fight the pernicious effects of what he called the “equality premise” but to better recognize and organize patterns of aptitude in a changing economy.

Though it’s not part of conventional wisdom about the ideological core of neoliberalism, this appeal to nature was a central part of neoliberal thought in the aftermath of the Cold War. Communism had died, but neoliberals feared Leviathan would live on. The poison of civil rights, feminism, affirmative action, and ecological consciousness—forged in the social movements of the 1960s and ’70s—had suffused the body politic, emboldening what they saw as an overbearing state and breeding an atmosphere of political correctness and “victimology,” which in turn stultified free discourse and nurtured a culture of government dependency and special pleading.

Neoliberals sought an antidote to all that, and they found one in hierarchies of gender, race, and cultural difference, which they imagined to be rooted in genetics as well as tradition. Meanwhile, changing demographics—an aging white population matched by an expanding nonwhite population—led some of them to rethink the conditions necessary for capitalism. Perhaps cultural homogeneity was a precondition for social stability, and thus the peaceful conduct of market exchange and enjoyment of private property?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Today’s AI technologies are based on deep learning, yet “AI” is commonly equated with large language models, and the fundamental nature of deep learning and LLMs is obscured by talk of using “statistical patterns” to “predict tokens”. This token-focused framing has been a remarkably effective way to misunderstand AI.

Today’s AI technologies are based on deep learning, yet “AI” is commonly equated with large language models, and the fundamental nature of deep learning and LLMs is obscured by talk of using “statistical patterns” to “predict tokens”. This token-focused framing has been a remarkably effective way to misunderstand AI.

In recent decades, a paradox has haunted American political life. Given that political progressives wielded considerable political, economic, and cultural influence, how is it possible that our actual social order was so resistant to real change? Why did the black-white wealth gap remain unchanged, and why did economic inequality steadily increase? Why did basic access to affordable housing plummet? And why has higher education become a nightmarish debt sentence for poor and underprivileged people seeking a better life?

In recent decades, a paradox has haunted American political life. Given that political progressives wielded considerable political, economic, and cultural influence, how is it possible that our actual social order was so resistant to real change? Why did the black-white wealth gap remain unchanged, and why did economic inequality steadily increase? Why did basic access to affordable housing plummet? And why has higher education become a nightmarish debt sentence for poor and underprivileged people seeking a better life? Mishra is a relative latecomer to the Palestinian cause. It was Israeli heroes, not Arabs, with whom he was infatuated as a boy growing up in India: he even had a picture on his wall of Moshe Dayan, Israel’s defence minister during the Six Day War. Conversion came during a 2008 visit to Israel-Palestine, where Mishra was shocked to witness the humiliations heaped on the inhabitants of the West Bank. “Nothing prepared me for the brutality and squalor of Israel’s occupation,” he writes, “the snaking wall and numerous roadblocks … meant to torment Palestinians in their own land … the racially exclusive network of shiny asphalt roads, electricity grids and water systems linking the illegal Jewish settlements to Israel.”

Mishra is a relative latecomer to the Palestinian cause. It was Israeli heroes, not Arabs, with whom he was infatuated as a boy growing up in India: he even had a picture on his wall of Moshe Dayan, Israel’s defence minister during the Six Day War. Conversion came during a 2008 visit to Israel-Palestine, where Mishra was shocked to witness the humiliations heaped on the inhabitants of the West Bank. “Nothing prepared me for the brutality and squalor of Israel’s occupation,” he writes, “the snaking wall and numerous roadblocks … meant to torment Palestinians in their own land … the racially exclusive network of shiny asphalt roads, electricity grids and water systems linking the illegal Jewish settlements to Israel.”

Once upon a time, during the last quarter of the 20th century, it was possible to argue that one person was America’s best novelist and best literary critic. I am talking about John Updike, whose long and elegant reviews in The New Yorker set reading agendas. Such was Updike’s influence that readers paid heed when, in the mid-1980s, he developed a sustained literary man-crush on the Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa, who died on Sunday at 89.

Once upon a time, during the last quarter of the 20th century, it was possible to argue that one person was America’s best novelist and best literary critic. I am talking about John Updike, whose long and elegant reviews in The New Yorker set reading agendas. Such was Updike’s influence that readers paid heed when, in the mid-1980s, he developed a sustained literary man-crush on the Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa, who died on Sunday at 89. T

T THE world is angry — and in most places, women bear the brunt of this anger. This International Women’s Day, the

THE world is angry — and in most places, women bear the brunt of this anger. This International Women’s Day, the  In our culture, music is most often written about in terms of sales, streams and chart positions. That is, of course, the least intelligent way to think about or talk about music.

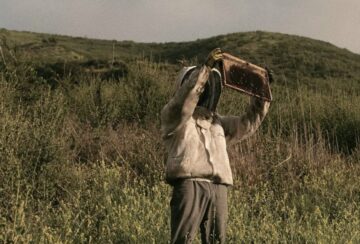

In our culture, music is most often written about in terms of sales, streams and chart positions. That is, of course, the least intelligent way to think about or talk about music. I have loved bees

I have loved bees