There is No Word

There isn’t a word for walking out of the grocery store

with a gallon jug of milk in a plastic sack

that should have been bagged in double layers

—so that before you are even out the door

you feel the weight of the jug dragging

the bag down, stretching the thin

plastic handles longer and longer

and you know it’s only a matter of time until

the bottom suddenly splits.

There is no single, unimpeachable word

for that vague sensation of something

moving away from you

as it exceeds its elastic capacity

—which is too bad, because that is the word

I would like to use to describe standing on the street

chatting with an old friend

as the awareness grows in me that he is

no longer a friend, but only an acquaintance,

a person with whom I never made the effort—

until this moment, when as we say goodbye

I think we share a feeling of relief,

a recognition that we have reached

the end of a pretense,

though to tell the truth

what I already am thinking about

is my gratitude for language—

how it will stretch just so much and no farther;

how there are some holes it will not cover up;

how it will move, if not inside, then

around the circumference of almost anything—

how, over the years, it has given me

back all the hours and days, all the

plodding love and faith, all the

misunderstandings and secrets

I have willingly poured into it.

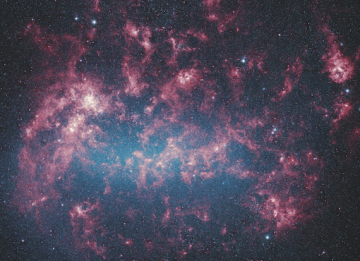

Most of the Universe is missing and decades of searching have so far elicited no sign of it. For some scientists this is an embarrassment. For others it is a clue that might eventually push physics towards the next frontier of understanding. Either way, it is an odd situation.

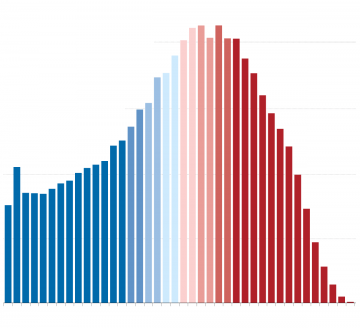

Most of the Universe is missing and decades of searching have so far elicited no sign of it. For some scientists this is an embarrassment. For others it is a clue that might eventually push physics towards the next frontier of understanding. Either way, it is an odd situation. It’s true across many industrialized democracies that rural areas lean conservative while cities tend to be more liberal, a pattern partly rooted in the history of workers’ parties that grew up where urban factories did.

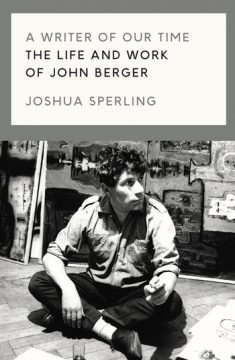

It’s true across many industrialized democracies that rural areas lean conservative while cities tend to be more liberal, a pattern partly rooted in the history of workers’ parties that grew up where urban factories did. John Berger became a writer you might find on television because of Ways of Seeing, the 1972 BBC series that became a short and very famous book. The show presented observations now common to pop-culture reviews—publicity “proposes to each of us that we transform ourselves, or our lives, by buying something more”—in a place (a box!) that rarely admitted critique beyond yea or nay. The book version of Ways of Seeing, which combined photos and text in a montage format, is now a staple of critical-writing syllabi. Writers like Laura Mulvey and Rosalind Krauss wrote the definitive versions of theories Berger proposed, and dozens of critics have put in decades peeling back the semiotic layers of images. Berger simply made it seem plausible that there would be an audience—possibly a big one—for this kind of thinking. In May of 2017, four months after Berger’s death, feminist media scholar Jane Gaines wrote about Ways of Seeing: “We learned from him to see that basic assumptions about everything—work, play, art, commerce—are hidden in the surrounding culture of images.”

John Berger became a writer you might find on television because of Ways of Seeing, the 1972 BBC series that became a short and very famous book. The show presented observations now common to pop-culture reviews—publicity “proposes to each of us that we transform ourselves, or our lives, by buying something more”—in a place (a box!) that rarely admitted critique beyond yea or nay. The book version of Ways of Seeing, which combined photos and text in a montage format, is now a staple of critical-writing syllabi. Writers like Laura Mulvey and Rosalind Krauss wrote the definitive versions of theories Berger proposed, and dozens of critics have put in decades peeling back the semiotic layers of images. Berger simply made it seem plausible that there would be an audience—possibly a big one—for this kind of thinking. In May of 2017, four months after Berger’s death, feminist media scholar Jane Gaines wrote about Ways of Seeing: “We learned from him to see that basic assumptions about everything—work, play, art, commerce—are hidden in the surrounding culture of images.” And we abolish the idea of hell at the very moment when it could be the most pertinent to us. An ironic reality in an era where the world becomes seemingly more hellish, when humanity has developed the ability to enact a type of burning punishment upon the earth itself. Journalist David Wallace-Wells in his terrifying new book about climate change The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming writes that “it is much, much worse, than you think.” Wallace-Wells goes onto describe how anthropogenic warming will result in a twenty-first century that sees coastal cities destroyed and refugees forced to migrate for survival, that will see famines across formerly verdant farm lands and the development of new epidemics that will kill millions, which will see wars fought over fresh water and wildfires scorching the wilderness. Climate change implies not just ecological collapse, but societal, political, and moral collapse as well. The science has been clear for over a generation, our reliance on fossil fuels has been hastening an industrial apocalypse of our own invention. Wallace-Wells is critical of what he describes as the “eerily banal language of climatology,” where the purposefully sober, logical, and rational arguments of empirical science have unintentionally helped to obscure the full extent of what some studying climate change now refer to as our coming “century of hell.” Better perhaps to have this discussion using the language of Revelation, where the horseman of pestilence, war, famine, and death are powered by carbon dioxide.

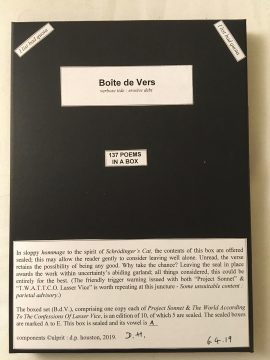

And we abolish the idea of hell at the very moment when it could be the most pertinent to us. An ironic reality in an era where the world becomes seemingly more hellish, when humanity has developed the ability to enact a type of burning punishment upon the earth itself. Journalist David Wallace-Wells in his terrifying new book about climate change The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming writes that “it is much, much worse, than you think.” Wallace-Wells goes onto describe how anthropogenic warming will result in a twenty-first century that sees coastal cities destroyed and refugees forced to migrate for survival, that will see famines across formerly verdant farm lands and the development of new epidemics that will kill millions, which will see wars fought over fresh water and wildfires scorching the wilderness. Climate change implies not just ecological collapse, but societal, political, and moral collapse as well. The science has been clear for over a generation, our reliance on fossil fuels has been hastening an industrial apocalypse of our own invention. Wallace-Wells is critical of what he describes as the “eerily banal language of climatology,” where the purposefully sober, logical, and rational arguments of empirical science have unintentionally helped to obscure the full extent of what some studying climate change now refer to as our coming “century of hell.” Better perhaps to have this discussion using the language of Revelation, where the horseman of pestilence, war, famine, and death are powered by carbon dioxide. I received d.p. houston’s poetry collection Boîte de Vers in the post last week. It’s completely unreadable, but not in the sense that it’s bad. It could well be, but I have no idea because it comes in a sealed box, ‘in sloppy hommage to the spirit of Schrödinger’s Cat’. There are apparently five of these boxes in circulation; mine is lettered A. The precise nature of its contents is indeterminate. I could break the seal of strong black tape and open the box, but doing so would alter it. Not least because I would then be required to fill in the attached label with a cross or tick ‘to indicate whether or not the intrusion comes to be regretted’. It feels like a puzzle, or a personality test: what kind of person would open the box?

I received d.p. houston’s poetry collection Boîte de Vers in the post last week. It’s completely unreadable, but not in the sense that it’s bad. It could well be, but I have no idea because it comes in a sealed box, ‘in sloppy hommage to the spirit of Schrödinger’s Cat’. There are apparently five of these boxes in circulation; mine is lettered A. The precise nature of its contents is indeterminate. I could break the seal of strong black tape and open the box, but doing so would alter it. Not least because I would then be required to fill in the attached label with a cross or tick ‘to indicate whether or not the intrusion comes to be regretted’. It feels like a puzzle, or a personality test: what kind of person would open the box? Minute fossils pulled from remote Arctic Canada could push back the first known appearance of fungi to about one billion years ago — more than 500 million years earlier than scientists had expected. These ur-fungi, described on 22 May in Nature

Minute fossils pulled from remote Arctic Canada could push back the first known appearance of fungi to about one billion years ago — more than 500 million years earlier than scientists had expected. These ur-fungi, described on 22 May in Nature Dear Massimo,

Dear Massimo, For me personally, the vision that became Wolfram|Alpha has a very long history. I first imagined creating something like it more than 47 years ago,

For me personally, the vision that became Wolfram|Alpha has a very long history. I first imagined creating something like it more than 47 years ago,  Sometimes, it is the very ordinariness of a scene that makes it terrifying. So it was with a clip from last week’s BBC

Sometimes, it is the very ordinariness of a scene that makes it terrifying. So it was with a clip from last week’s BBC  LATE IN THE

LATE IN THE  Plastic makes up nearly 70% of all ocean litter

Plastic makes up nearly 70% of all ocean litter It’s amazing that this landmark symphony could have been so easily forgotten. As with the other seminal New Englanders—George Whitefield Chadwick, Horatio Parker, and Edward MacDowell, among them—modernism killed off Paine’s music. And with the ascendancy of American vernacular forms, reflected in the music of Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and others, any music arising from the German Romantic tradition could be ridiculed and ignored. Paine may have been the acknowledged dean of a New England school, but he could not be comfortably located with any American school. Even Paine’s student Richard Aldrich, writing in the early 20th century, argued that Paine’s music, despite its “fertility,” “genuine warmth,” “spontaneity of invention,” and “fine harmonic feeling,” did not “disclose ‘American’ characteristics.” But what in Paine’s time and cultural milieu would have constituted an American characteristic?

It’s amazing that this landmark symphony could have been so easily forgotten. As with the other seminal New Englanders—George Whitefield Chadwick, Horatio Parker, and Edward MacDowell, among them—modernism killed off Paine’s music. And with the ascendancy of American vernacular forms, reflected in the music of Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and others, any music arising from the German Romantic tradition could be ridiculed and ignored. Paine may have been the acknowledged dean of a New England school, but he could not be comfortably located with any American school. Even Paine’s student Richard Aldrich, writing in the early 20th century, argued that Paine’s music, despite its “fertility,” “genuine warmth,” “spontaneity of invention,” and “fine harmonic feeling,” did not “disclose ‘American’ characteristics.” But what in Paine’s time and cultural milieu would have constituted an American characteristic? Somehow I became respectable. I don’t know how—the last film I directed got some terrible reviews and was rated NC-17. Six people in my personal phone book have been sentenced to life in prison. I did an art piece called Twelve Assholes and a Dirty Foot, which is composed of close-ups from porn films, yet a museum now has it in their permanent collection and nobody got mad. What the hell has happened?

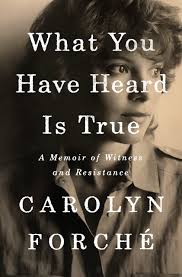

Somehow I became respectable. I don’t know how—the last film I directed got some terrible reviews and was rated NC-17. Six people in my personal phone book have been sentenced to life in prison. I did an art piece called Twelve Assholes and a Dirty Foot, which is composed of close-ups from porn films, yet a museum now has it in their permanent collection and nobody got mad. What the hell has happened? There is a lot of horror in this book. People are thrown from helicopters into the sea, their arms tied behind their backs. A colonel grinds up his victims’ bodies and feeds them to his dogs. Forché finds mutilated corpses by the side of the road. She visits a prison where men are kept in cages the size of washing machines. She and a friend are pursued by an escuadrón de la muerte (death squad). Later, she meets a man who was a member of one such squad, who recalls the sound of bubbles as he cut his victims’ throats.

There is a lot of horror in this book. People are thrown from helicopters into the sea, their arms tied behind their backs. A colonel grinds up his victims’ bodies and feeds them to his dogs. Forché finds mutilated corpses by the side of the road. She visits a prison where men are kept in cages the size of washing machines. She and a friend are pursued by an escuadrón de la muerte (death squad). Later, she meets a man who was a member of one such squad, who recalls the sound of bubbles as he cut his victims’ throats.