John Ortved in Document:

Why do we like what we like? The books, movies, photos, and artworks that form our perspective—who puts them in front of us? One answer is the critic, that cipher of taste who places art in its various corridors, then augments, defines, degrades, and ultimately shapes the works that shape us. In times when the public’s eye travels with ever more scope but not necessarily more depth, criticism, the act of choosing—and so much more—becomes more important than ever. It’s for this reason that so many eyes are turning to Parul Sehgal and Teju Cole, two critics—as well as editors, essayists, and artists—challenging not only us but art forms themselves.

Why do we like what we like? The books, movies, photos, and artworks that form our perspective—who puts them in front of us? One answer is the critic, that cipher of taste who places art in its various corridors, then augments, defines, degrades, and ultimately shapes the works that shape us. In times when the public’s eye travels with ever more scope but not necessarily more depth, criticism, the act of choosing—and so much more—becomes more important than ever. It’s for this reason that so many eyes are turning to Parul Sehgal and Teju Cole, two critics—as well as editors, essayists, and artists—challenging not only us but art forms themselves.

At only 37, Sehgal is re-centering literature from her position as literary critic and columnist at The New York Times. (She was hired after the Times’s chief literary critic, Michiko Kakutani, stepped down in 2017). Her choice of subjects and focused, artful prose is giving space to works by marginalized authors, including women and people of color, as well as international identities and cultures historically left out of the canon. As we continue to look to the written word for clarity, hope, and maybe even answers, work by Sehgal—who teaches at Columbia University and won the 2010 Nona Balakian Award from the National Book Critics Circle—has become nothing short of essential reading.

Meanwhile, Cole is directing our gaze from various esteemed perches, be it his role as the first Gore Vidal Professor of the Practice of Creative Writing at Harvard, his job as the photography critic for The New York Times Magazine, as the PEN/Hemingway Award-winning author of Open City, or as an internationally exhibited photographer. Our eyes follow his, even if we’re not aware of it.

More here.

Most people in the modern world — and the vast majority of Mindscape listeners, I would imagine — agree that humans are part of the animal kingdom, and that all living animals evolved from a common ancestor. Nevertheless, there are ways in which we are unique; humans are the only animals that stress out over Game of Thrones (as far as I know). I talk with geneticist and science writer Adam Rutherford about what makes us human, and how we got that way, both biologically and culturally. One big takeaway lesson is that it’s harder to find firm distinctions than you might think; animals use language and tools and fire, and have way more inventive sex lives than we do.

Most people in the modern world — and the vast majority of Mindscape listeners, I would imagine — agree that humans are part of the animal kingdom, and that all living animals evolved from a common ancestor. Nevertheless, there are ways in which we are unique; humans are the only animals that stress out over Game of Thrones (as far as I know). I talk with geneticist and science writer Adam Rutherford about what makes us human, and how we got that way, both biologically and culturally. One big takeaway lesson is that it’s harder to find firm distinctions than you might think; animals use language and tools and fire, and have way more inventive sex lives than we do. Earlier this year, the presidents of Sudan and Algeria both announced they would step aside

Earlier this year, the presidents of Sudan and Algeria both announced they would step aside  A

A  Scientists have created a living organism whose DNA is entirely human-made — perhaps a new form of life, experts said, and a milestone in the field of synthetic biology. Researchers at the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Britain reported on Wednesday that they had rewritten the DNA of the bacteria Escherichia coli, fashioning a synthetic genome four times larger and far more complex than any previously created. The bacteria are alive, though unusually shaped and reproducing slowly. But their cells operate according to a new set of biological rules, producing familiar proteins with a reconstructed genetic code. The achievement one day may lead to organisms that produce novel medicines or other valuable molecules, as living factories. These synthetic bacteria also may offer clues as to how the genetic code arose in the early history of life.

Scientists have created a living organism whose DNA is entirely human-made — perhaps a new form of life, experts said, and a milestone in the field of synthetic biology. Researchers at the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Britain reported on Wednesday that they had rewritten the DNA of the bacteria Escherichia coli, fashioning a synthetic genome four times larger and far more complex than any previously created. The bacteria are alive, though unusually shaped and reproducing slowly. But their cells operate according to a new set of biological rules, producing familiar proteins with a reconstructed genetic code. The achievement one day may lead to organisms that produce novel medicines or other valuable molecules, as living factories. These synthetic bacteria also may offer clues as to how the genetic code arose in the early history of life. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have gone on so long that the Middle East war novel has itself become a crusty genre — a familiar set of echoes coming back to us from ravaged lands. Many of these books are stirring on the level of detail but an equal number thoughtlessly valorize the American soldier or wallow in the morally vacuous conclusion that war is hell and that’s that. Where is the ferocious “Catch-22” of these benighted conflicts? Who will have the temerity to make these wars the subject of bracing comedy?

The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have gone on so long that the Middle East war novel has itself become a crusty genre — a familiar set of echoes coming back to us from ravaged lands. Many of these books are stirring on the level of detail but an equal number thoughtlessly valorize the American soldier or wallow in the morally vacuous conclusion that war is hell and that’s that. Where is the ferocious “Catch-22” of these benighted conflicts? Who will have the temerity to make these wars the subject of bracing comedy? Jared Diamond’s new book,

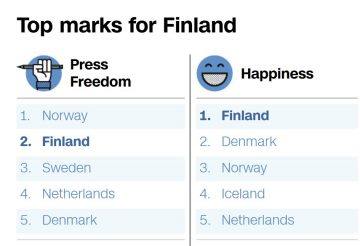

Jared Diamond’s new book,  On a recent afternoon in Helsinki, a group of students gathered to hear a lecture on a subject that is far from a staple in most community college curriculums.

On a recent afternoon in Helsinki, a group of students gathered to hear a lecture on a subject that is far from a staple in most community college curriculums. This January, Hussein Fancy, an American academic of Pakistani origin, received the Herbert Baxter Adams Prize, awarded annually by the American Historical Association “to honor a distinguished book published in English in the field of European history,” for his groundbreaking work The Mercenary Mediterranean: Sovereignty, Religion, and Violence in the Medieval Crown of Aragon. This isn’t the first prize awarded to this book: it had earlier been the recipient of the Jans F. Verbruggen Prize from De Re Militari for the best book in medieval military history and the L. Carl Brown AIMS Book Prize in North African Studies. These three very different prizes, each with different parameters, indicate the range and importance of Fancy’s research.

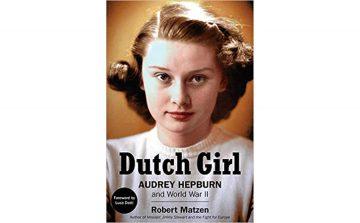

This January, Hussein Fancy, an American academic of Pakistani origin, received the Herbert Baxter Adams Prize, awarded annually by the American Historical Association “to honor a distinguished book published in English in the field of European history,” for his groundbreaking work The Mercenary Mediterranean: Sovereignty, Religion, and Violence in the Medieval Crown of Aragon. This isn’t the first prize awarded to this book: it had earlier been the recipient of the Jans F. Verbruggen Prize from De Re Militari for the best book in medieval military history and the L. Carl Brown AIMS Book Prize in North African Studies. These three very different prizes, each with different parameters, indicate the range and importance of Fancy’s research. Audrey Hepburn was one of the most celebrated actresses of the 20th century and a winner of Academy, Tony, Grammy, and Emmy awards. She was a style icon and, in later life, a tireless humanitarian who worked to improve conditions for children in some of the poorest communities in Africa and Asia as an ambassador for UNICEF. But this extraordinary individual was the product of an extremely difficult childhood. Her father was a British subject and something of a rake and her mother was a minor Dutch noblewoman. Both of her parents flirted with the Nazis in the 1930s. Her mother met Adolf Hitler and wrote favorable articles about him for the British Union of Fascists. After abandoning the family in 1935, her father moved to England and became so active with Oswald Mosley’s fascists that he was interned during World War II. As a child, Hepburn rarely saw him.

Audrey Hepburn was one of the most celebrated actresses of the 20th century and a winner of Academy, Tony, Grammy, and Emmy awards. She was a style icon and, in later life, a tireless humanitarian who worked to improve conditions for children in some of the poorest communities in Africa and Asia as an ambassador for UNICEF. But this extraordinary individual was the product of an extremely difficult childhood. Her father was a British subject and something of a rake and her mother was a minor Dutch noblewoman. Both of her parents flirted with the Nazis in the 1930s. Her mother met Adolf Hitler and wrote favorable articles about him for the British Union of Fascists. After abandoning the family in 1935, her father moved to England and became so active with Oswald Mosley’s fascists that he was interned during World War II. As a child, Hepburn rarely saw him. It’s a well-known saying that women lost us the empire,” the film director David Lean said in 1985. “It’s true.” He’d just released his acclaimed adaptation of A Passage to India, EM Forster’s novel in which a British woman’s accusation of sexual assault compromises a friendship between British and Indian men. Misogyny may not be the first prejudice associated with British imperialists, but it has proved as enduring as it was powerful. As Katie Hickman discovered when she started writing about British women in India, Lean’s view (if not Forster’s) “remains stubbornly embedded in our consciousness”. “Everyone” she talked to “knew that if it were not for the snobbery and racial prejudice of the memsahibs there would, somehow, have been far greater harmony and accord between the races”. Her book, vivaciously written and richly descriptive, offers a rebuke to such stereotypes. She animates a cast of British women who travelled to India before the 1857 rebellion. They included “bakers, dressmakers, actresses, portrait painters, maids, shopkeepers, governesses, teachers, boarding house proprietors … missionaries, doctors, geologists, plant-collectors, writers … even traders” – and some of them might not have been out of place in a Lean epic of their own.

It’s a well-known saying that women lost us the empire,” the film director David Lean said in 1985. “It’s true.” He’d just released his acclaimed adaptation of A Passage to India, EM Forster’s novel in which a British woman’s accusation of sexual assault compromises a friendship between British and Indian men. Misogyny may not be the first prejudice associated with British imperialists, but it has proved as enduring as it was powerful. As Katie Hickman discovered when she started writing about British women in India, Lean’s view (if not Forster’s) “remains stubbornly embedded in our consciousness”. “Everyone” she talked to “knew that if it were not for the snobbery and racial prejudice of the memsahibs there would, somehow, have been far greater harmony and accord between the races”. Her book, vivaciously written and richly descriptive, offers a rebuke to such stereotypes. She animates a cast of British women who travelled to India before the 1857 rebellion. They included “bakers, dressmakers, actresses, portrait painters, maids, shopkeepers, governesses, teachers, boarding house proprietors … missionaries, doctors, geologists, plant-collectors, writers … even traders” – and some of them might not have been out of place in a Lean epic of their own. Emily Wilson in The New Statesman:

Emily Wilson in The New Statesman: Jan-Werner Müller in The Nation:

Jan-Werner Müller in The Nation: Over at The Hedgehog & the Fox, an interview with Rachel Sherman:

Over at The Hedgehog & the Fox, an interview with Rachel Sherman: