by Elizabeth S. Bernstein

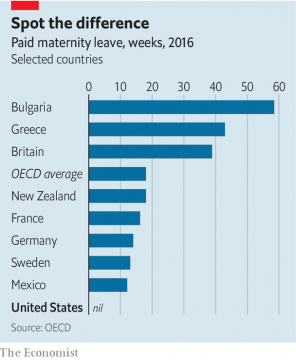

The United States continues to be virtually the only developed country which does not guarantee any paid time off work to new parents. A study recently released by the New America think tank explores the “complicated, confusing, and uneven leave landscape for workers,” and the behaviors that result. The federal Family and Medical Leave Act entitles workers only to unpaid time off, and many employers and workers do not fall even within that mandate. While some employers, and public insurance programs in some states, do offer paid family leave, such benefits were found less likely to be available to lower-income households and to workers without college degrees.

The United States continues to be virtually the only developed country which does not guarantee any paid time off work to new parents. A study recently released by the New America think tank explores the “complicated, confusing, and uneven leave landscape for workers,” and the behaviors that result. The federal Family and Medical Leave Act entitles workers only to unpaid time off, and many employers and workers do not fall even within that mandate. While some employers, and public insurance programs in some states, do offer paid family leave, such benefits were found less likely to be available to lower-income households and to workers without college degrees.

According to the New America researchers, nearly half of the parents they surveyed reported taking no leave after the birth or adoption of a child. The weight of this finding is underscored by the definition the researchers used for “leave” – namely, anything “more than a day or two off work,” paid or unpaid. The mothers and fathers who reported taking no leave had not, in other words, taken even three days off work.

As documented in a previous report from New America, job-protected paid family leaves are associated with improved physical and mental health for both children and parents. This new research could therefore serve as yet another reminder of the deleterious effects of the family leave policies we have had, and continue to have, in the United States.

What a shame then, to see the study treated as if its primary contribution was to have turned up a previously unappreciated form of gender discrimination. The headline in HuffPost was this: “Even When Men Take Parental Leave, They’re Paid More, New Study Finds.” Great click-bait, and also completely misleading. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Rorschach on the River Li. Yangshuo, China, January, 2020.

Sughra Raza. Rorschach on the River Li. Yangshuo, China, January, 2020. While you might not break into a neighbor’s house to log onto your Facebook account if your internet were down, a case can be made that many of us are victims of at least a moderate behavioral addiction when it comes to our smartphones. At the playground with our kids, we’re on our phones. At dinner with friends, we’re on our phones. In the middle of the night. At the movies. At a concert. At a funeral. (I was recently at a memorial service for my friend’s mother, and someone’s cell phone rang during my friend’s reminiscence.)

While you might not break into a neighbor’s house to log onto your Facebook account if your internet were down, a case can be made that many of us are victims of at least a moderate behavioral addiction when it comes to our smartphones. At the playground with our kids, we’re on our phones. At dinner with friends, we’re on our phones. In the middle of the night. At the movies. At a concert. At a funeral. (I was recently at a memorial service for my friend’s mother, and someone’s cell phone rang during my friend’s reminiscence.)

When Vienna‘s Albertina Museum exhibition of works by Albrecht Dürer ended in January 2020, it seemed quite possible that several of the masterpieces on display might never again be seen by the public, among them The Great Piece of Turf. This may sound like a dire prediction for a fragile work that is routinely exhibited every decade or so, but as the UN announced recently, we may already have passed the tipping point in the race to save our world and ourselves. A decade from now we may be too engaged in the struggle to survive to focus our attention on a small, exquisite watercolor created 500 years ago.

When Vienna‘s Albertina Museum exhibition of works by Albrecht Dürer ended in January 2020, it seemed quite possible that several of the masterpieces on display might never again be seen by the public, among them The Great Piece of Turf. This may sound like a dire prediction for a fragile work that is routinely exhibited every decade or so, but as the UN announced recently, we may already have passed the tipping point in the race to save our world and ourselves. A decade from now we may be too engaged in the struggle to survive to focus our attention on a small, exquisite watercolor created 500 years ago.

During my late 1970s New York City childhood, repeats of Star Trek aired every weeknight on channel 11, WPIX. The original 79 episodes ran about three times per year, which means that, allowing for the occasional miss, I’d seen each episode about 10 – 12 times before reaching high school.

During my late 1970s New York City childhood, repeats of Star Trek aired every weeknight on channel 11, WPIX. The original 79 episodes ran about three times per year, which means that, allowing for the occasional miss, I’d seen each episode about 10 – 12 times before reaching high school. For the last three years, I have struggled with a dilemma: As a reasonable, quite liberal person, what should I think of my 60 million fellow Americans who voted for Donald Trump in 2016, and the vast majority of whom continue to support him today? Normally, a personal dilemma is a private thing, not a topic for public airing, but I feel that this particular problem is one the vexes many others – perhaps even a majority of Americans, as more of us voted for Hillary Clinton and many did not vote at all. Since that bleak day in November 2016, an unspoken – and sometimes loudly spoken – question hangs in the air: What kind of “

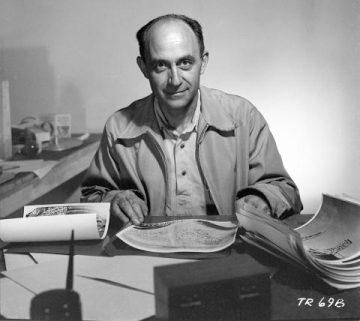

For the last three years, I have struggled with a dilemma: As a reasonable, quite liberal person, what should I think of my 60 million fellow Americans who voted for Donald Trump in 2016, and the vast majority of whom continue to support him today? Normally, a personal dilemma is a private thing, not a topic for public airing, but I feel that this particular problem is one the vexes many others – perhaps even a majority of Americans, as more of us voted for Hillary Clinton and many did not vote at all. Since that bleak day in November 2016, an unspoken – and sometimes loudly spoken – question hangs in the air: What kind of “ In November 1918, a 17-year-student from Rome sat for the entrance examination of the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, Italy’s most prestigious science institution. Students applying to the institute had to write an essay on a topic that the examiners picked. The topics were usually quite general, so the students had considerable leeway. Most students wrote about well-known subjects that they had already learnt about in high school. But this student was different. The title of the topic he had been given was “Characteristics of Sound”, and instead of stating basic facts about sound, he “set forth the partial differential equation of a vibrating rod and solved it using Fourier analysis, finding the eigenvalues and eigenfrequencies. The entire essay continued on this level which would have been creditable for a doctoral examination.” The man writing these words was the 17-year-old’s future student, friend and Nobel laureate, Emilio Segre. The student was Enrico Fermi. The examiner was so startled by the originality and sophistication of Fermi’s analysis that he broke precedent and invited the boy to meet him in his office, partly to make sure that the essay had not been plagiarized. After convincing himself that Enrico had done the work himself, the examiner congratulated him and predicted that he would become an important scientist.

In November 1918, a 17-year-student from Rome sat for the entrance examination of the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, Italy’s most prestigious science institution. Students applying to the institute had to write an essay on a topic that the examiners picked. The topics were usually quite general, so the students had considerable leeway. Most students wrote about well-known subjects that they had already learnt about in high school. But this student was different. The title of the topic he had been given was “Characteristics of Sound”, and instead of stating basic facts about sound, he “set forth the partial differential equation of a vibrating rod and solved it using Fourier analysis, finding the eigenvalues and eigenfrequencies. The entire essay continued on this level which would have been creditable for a doctoral examination.” The man writing these words was the 17-year-old’s future student, friend and Nobel laureate, Emilio Segre. The student was Enrico Fermi. The examiner was so startled by the originality and sophistication of Fermi’s analysis that he broke precedent and invited the boy to meet him in his office, partly to make sure that the essay had not been plagiarized. After convincing himself that Enrico had done the work himself, the examiner congratulated him and predicted that he would become an important scientist.

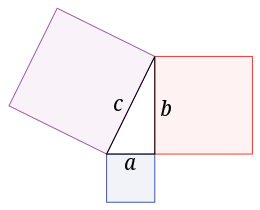

I have some very simple New Year’s resolutions, and some that require an entire column to spell out. One example of the latter is that I want to make a subtle but meaningful change in how I talk to my (middle and high school) math students about proofs.

I have some very simple New Year’s resolutions, and some that require an entire column to spell out. One example of the latter is that I want to make a subtle but meaningful change in how I talk to my (middle and high school) math students about proofs.