Category: Archives

18 Organizations, 246 Scientists and Scholars Send Letter to New Director of NIH, Urging Shift Away From Animal Use in Medical Research

From Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine:

WASHINGTON, D.C.—A group of scientists, physicians, ethicists, and advocates sent a letter this Wednesday to the newly confirmed director of the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Monica Bertagnolli, urging her to reduce the agency’s use of animals in medical research. Led by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine and co-signed by 246 individuals and 18 organizations, including biotechnology companies, think tanks, and animal protection groups, the letter requests that Dr. Bertagnolli prioritizes funding for developing, validating, and using nonanimal human disease models. It also requests divestment from animal use in research areas where poorly predicted human outcomes have been demonstrated, such as vaccine development and liver toxicity.

WASHINGTON, D.C.—A group of scientists, physicians, ethicists, and advocates sent a letter this Wednesday to the newly confirmed director of the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Monica Bertagnolli, urging her to reduce the agency’s use of animals in medical research. Led by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine and co-signed by 246 individuals and 18 organizations, including biotechnology companies, think tanks, and animal protection groups, the letter requests that Dr. Bertagnolli prioritizes funding for developing, validating, and using nonanimal human disease models. It also requests divestment from animal use in research areas where poorly predicted human outcomes have been demonstrated, such as vaccine development and liver toxicity.

The NIH is the largest funder of biomedical research in the world, overseeing a budget of nearly $50 billion this fiscal year. Despite evidence that animal experiments are unreliable predictors of human physiology and disease states, they remain the presumed “gold standard” in basic and preclinical research by the NIH and others within the research community. This reliance on animals contributes to failures and wasteful spending in the drug development pipeline and puts clinical trial participants at risk by failing to capture unsafe or ineffective products. It also requires that untold numbers of dogs, cats, monkeys, mice, rats, and other animals be bred and used in painful and deadly procedures—estimated to be greater than 100 million per year in the U.S.

More here.

How wild monkeys ‘laundered’ for science could undermine research

Gemma Conroy in Nature:

In 2019, immunologist Jonah Sacha received a shipment of monkeys for his research into infectious diseases. But while conducting preliminary chest X-rays, Sacha found one monkey that stood out for all the wrong reasons: it was carrying the bacterium that causes tuberculosis (TB). The infected animal rendered the entire shipment of 20 monkeys unusable for research because of the risk that the infection would spread. “We lost all of those animals,” says Sacha, who investigates stem-cell transplants as a treatment for HIV at the Oregon Health & Science University’s Oregon National Primate Research Center in Beaverton. “That cost hundreds of thousands of dollars of damage and delayed our research by many years.”

In 2019, immunologist Jonah Sacha received a shipment of monkeys for his research into infectious diseases. But while conducting preliminary chest X-rays, Sacha found one monkey that stood out for all the wrong reasons: it was carrying the bacterium that causes tuberculosis (TB). The infected animal rendered the entire shipment of 20 monkeys unusable for research because of the risk that the infection would spread. “We lost all of those animals,” says Sacha, who investigates stem-cell transplants as a treatment for HIV at the Oregon Health & Science University’s Oregon National Primate Research Center in Beaverton. “That cost hundreds of thousands of dollars of damage and delayed our research by many years.”

In a lot of ways, Sacha was lucky that he detected the diseased monkey: if it had made its way into a medical trial, it could have confounded the results, says Ricardo Carrion, a microbiologist at the Texas Biomedical Research Institute’s Southwest National Primate Research Center in San Antonio. Sacha doesn’t know how the monkeys got TB — research monkeys are typically captive-bred, which should guarantee that they are free of diseases. But the risk of disease is a growing concern among scientists who work with monkeys; news reports suggest that some laboratory monkeys are being illegally poached from the wild, falsely labelled as captive-bred and sold as research animals, a practice known as monkey laundering.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Above the River

I believe we’re all breakable

old bridges black paint &

rust building behind dirt

roads boarded up

unraveled with longing

looking down on some crazy

river world & driven so

when you brush

past me & honor my

shoulder with your small gift

of a hand because you just

can’t not all the sins of all

the people who never touched me

right seem forgiven

by Jim Bell

from Crossing the Bar

Slate Roof Publishing Collective

Northfield, Ma.

Wednesday, November 15, 2023

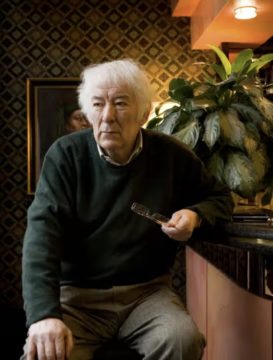

The Letters of Seamus Heaney

John Banville in The Guardian:

If letter writing is an art form, then Seamus Heaney was one of its master practitioners. Christopher Reid’s 800-page selection from what he assures us was an “enormous output” – “I have had to cut back severely to make a book of publishable proportions” – is a trove of delights as much as it is a literary testament.

If letter writing is an art form, then Seamus Heaney was one of its master practitioners. Christopher Reid’s 800-page selection from what he assures us was an “enormous output” – “I have had to cut back severely to make a book of publishable proportions” – is a trove of delights as much as it is a literary testament.

Heaney was as fluent in prose as he was sublime in verse, as readers will know from his essays and articles, and his extensive memoir, Stepping Stones, compiled in interview form with the poet Dennis O’Driscoll. Yet the style in the letters, many of them obviously composed at breakneck speed, is astonishing in its quality and unflagging grace. As one of his correspondents said of Heaney: “He makes the simplest words shine.”

Despite occasional asperities, his generosity and enthusiasm for the work of others are remarkable. Here he is writing in 2006 to Ted Hughes’s widow, Carol, about the poet’s posthumous Selected Translations – and note the beautifully sustained oceanic metaphor: “The delights are dolphin-like, the mighty talent rising again and showing his back above the elements … I got [the book] and swam in and out of the different coves and caves, safe havens (few) and strange strands. A strong sense of being lifted on the tide of it all.”

More here.

DeepMind AI can beat the best weather forecasts – but there is a catch

Matthew Sparkes in New Scientist:

AI can predict the weather 10 days ahead more accurately than current state-of-the-art simulations, says AI firm Google DeepMind – but meteorologists have warned against abandoning weather models based in real physical principles and just relying on patterns in data, while pointing out shortcomings in the AI approach.

AI can predict the weather 10 days ahead more accurately than current state-of-the-art simulations, says AI firm Google DeepMind – but meteorologists have warned against abandoning weather models based in real physical principles and just relying on patterns in data, while pointing out shortcomings in the AI approach.

Existing weather forecasts are based on mathematical models, which use physics and powerful supercomputers to deterministically predict what will happen in the future. These models have slowly become more accurate by adding finer detail, which in turn requires more computation and therefore ever more powerful computers and higher energy demands.

Rémi Lam at Google DeepMind and his colleagues have taken a different approach. Their GraphCast AI model is trained on four decades of historical weather data from satellites, radar and ground measurements, identifying patterns that not even Google DeepMind understands. “Like many machine-learning AI models, it’s not very easy to interpret how the model works,” says Lam.

More here.

Francis Bacon has been charged with robbing science of its innocence. But what if we’ve all been reading him wrong?

Louise Liebeskind in The New Atlantis:

Francis Bacon is known, above all, for conceiving of a great and terrible human project: the conquest of nature for “the relief of man’s estate.” This project, still ongoing, has its champions. “If the point of philosophy is to change the world,” Peter Thiel posits, “Sir Francis Bacon may be the most successful philosopher ever.” But critics abound. Bacon stands accused of alienating human beings from nature, abandoning the wisdom of the ancients, degrading a philosophy dedicated to the contemplation of truth, and replacing it with something cruder, a science of power.

Francis Bacon is known, above all, for conceiving of a great and terrible human project: the conquest of nature for “the relief of man’s estate.” This project, still ongoing, has its champions. “If the point of philosophy is to change the world,” Peter Thiel posits, “Sir Francis Bacon may be the most successful philosopher ever.” But critics abound. Bacon stands accused of alienating human beings from nature, abandoning the wisdom of the ancients, degrading a philosophy dedicated to the contemplation of truth, and replacing it with something cruder, a science of power.

In The Abolition of Man, C. S. Lewis goes so far as to compare Bacon to Christopher Marlowe’s Faustus:

You will read in some critics that Faustus has a thirst for knowledge. In reality, he hardly mentions it. It is not truth he wants … but gold and guns and girls. “All things that move between the quiet poles shall be at his command” and “a sound magician is a mighty god.” In the same spirit Bacon condemns those who value knowledge as an end in itself: this, for him, is to use as a mistress for pleasure what ought to be a spouse for fruit. The true object is to extend Man’s power to the performance of all things possible.

Lewis draws the final phrase of this critique from Bacon’s New Atlantis, the 1627 utopian novella from which this journal takes its name. But why would a publication like The New Atlantis, dedicated to the persistent questioning of science and technology, name itself after a philosopher’s utopian dreams about magicians on the verge of becoming mighty gods?

More here.

Martin Rees and Brian Greene Discuss the Past and Future of Life and the Cosmos

Wednesday Poem

The Such Thing As the Ridiculous Question –

Where are you from???

When I say ancestors, let’s be clear:

I mean slaves. I’m talkin’ Tennessee

cotton & Louisiana suga. I mean grave

dirt. I come from homes & marriages

named after the same type of weapon –

all it takes is a shotgun to know

I’m Black. I don’t got no secrets

a bullet ain’t told. Danger see me

& sit down somewhere.

I’m a direct descendant of last words

& first punches. I got stolen blood.

My complexion is America’s

darkest hour. You can trace my great

great great great great grandmother back

to a scream. I bet somewhere it’s a haint

with my eyes. My last name is a protest;

a brick through a window in a house

my bones built. One million

scabs from one scar.

Heavy is the hand that held

the whip. Black is the back that carried this

country & when this country’s palm gets

an itch, I become money. You give this country

an inch & it will take a freedom. You can’t talk slick

to this legacy of oiled scalps. You can’t spit

on my race & call it reign. I sound like my mama now,

who sound like her mama who sound like her mama who

sound like her mama, who sound like her

mama who sound like her mama who sound like her

mama who sound like her mama, who sound like a scream.

& that’s why I’m so loud, remember? You wanna know

where I’m from? Easy. Open a wound

& watch it heal.

by Siaara Freeman

from Split This Rock

The Whole World Is at Risk for ‘Compassion Fatigue’

Jamie Ducharme in Time Magazine:

After serving in the Vietnam War, Charles Figley became interested in the concept of trauma—not only the lasting psychological wounds that people experienced after living through traumatic events themselves, but also how their loved ones often came to share those burdens. “Simply being a member of a family and caring deeply about its members makes us emotionally vulnerable to the catastrophes which impact them,” he wrote in 1983.

After serving in the Vietnam War, Charles Figley became interested in the concept of trauma—not only the lasting psychological wounds that people experienced after living through traumatic events themselves, but also how their loved ones often came to share those burdens. “Simply being a member of a family and caring deeply about its members makes us emotionally vulnerable to the catastrophes which impact them,” he wrote in 1983.

At the time, Figley—who now runs the Tulane University Traumatology Institute—called these trickle-down effects “secondary traumatic stress reactions.” Today, however, he often uses the term “compassion fatigue” to refer to the emotional and physical exhaustion that sometimes afflicts people who are exposed to others’ trauma.

More here.

Psychology Lost a Great Mind

Steven Pinker in Nautilus:

On November 10, 2023, my dear friend John Tooby died—or as he would have put it, finally lost his struggle with entropy. John was a Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who together with his wife, Leda Cosmides, founded the field of evolutionary psychology. But that academic accomplishment doesn’t do him justice; it’s the institutional embodiment of the way his mind worked. John had insight into human nature worthy of our greatest novelists and playwrights, grounded in an understanding of the natural world worthy of our greatest scientists. Evolution for him was a link in an explanatory chain that connected human thought and feeling to the laws of the natural world.

On November 10, 2023, my dear friend John Tooby died—or as he would have put it, finally lost his struggle with entropy. John was a Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who together with his wife, Leda Cosmides, founded the field of evolutionary psychology. But that academic accomplishment doesn’t do him justice; it’s the institutional embodiment of the way his mind worked. John had insight into human nature worthy of our greatest novelists and playwrights, grounded in an understanding of the natural world worthy of our greatest scientists. Evolution for him was a link in an explanatory chain that connected human thought and feeling to the laws of the natural world.

It was this depth of thinking that made John’s company so precious. His conversations would mix sly observations of people’s foibles with profound allusions to science, history, and culture. Conference audiences forgave him for his famously discursive presentations, in which he might use up his time with a digression on the Big Bang before he ever got to the data.

Belying the canard that evolutionary psychology is a bunch of post hoc just-so stories, John, together with Leda and their students, published many experimental findings that confirmed nonobvious predictions about a wide range of psychological phenomena. These included statistical thinking, the perception of race, the development of sibling feelings, and the emotion of anger.

More here.

Louis Armstrong’s Last Word

Ethan Iverson at The Nation:

Ever since his seminal first recordings as a leader with his Hot Five and Seven ensembles in the 1920s, jazz musicians have called Louis Armstrong “Pops,” a literal invocation of his role as an ancestor. One of the greatest living practitioners of jazz, the trumpeter Tom Harrell, told me he’d heard a memorable pronouncement of Armstrong’s technical contribution from the saxophonist Phil Woods. Woods—a fluid master of the alto saxophone who is best known to the general public for his solo on Billy Joel’s “Just the Way You Are”—told Harrell, “Louis Armstrong was the first person to play behind the beat on record.”

Ever since his seminal first recordings as a leader with his Hot Five and Seven ensembles in the 1920s, jazz musicians have called Louis Armstrong “Pops,” a literal invocation of his role as an ancestor. One of the greatest living practitioners of jazz, the trumpeter Tom Harrell, told me he’d heard a memorable pronouncement of Armstrong’s technical contribution from the saxophonist Phil Woods. Woods—a fluid master of the alto saxophone who is best known to the general public for his solo on Billy Joel’s “Just the Way You Are”—told Harrell, “Louis Armstrong was the first person to play behind the beat on record.”

It’s a strong statement, but one that is borne out by a casual survey of the music recorded by others in the 1920s. Armstrong’s multimedia superstardom was the vessel for this subtle yet epochal reframing of the beat. Indeed, Armstrong’s rhythmic control could be his greatest legacy.

more here.

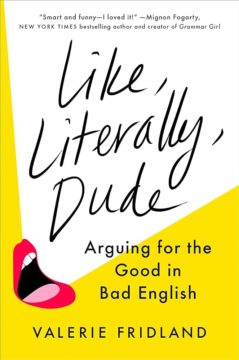

Arguing for the Good in Bad English

Florence Hazrat at Literary Review:

Take intensifiers like ‘totally’, ‘pretty’ and ‘completely’. We might consciously believe them to be exaggerations undermining the speaker’s point, yet people consistently report seeing linguistic booster-users as more authoritative and likeable than others.

Take intensifiers like ‘totally’, ‘pretty’ and ‘completely’. We might consciously believe them to be exaggerations undermining the speaker’s point, yet people consistently report seeing linguistic booster-users as more authoritative and likeable than others.

Then take ‘um’ and ‘uh’ (or ‘umm’ and ‘uhh’, and their consonant-multiplying siblings). Both receive an undue amount of flak for being fillers, supposedly deployed when the speaker is grasping for words, unsure what they want to say or lacking ideas. But this is not so. Fridland explains that they typically precede unfamiliar words or ideas, as well as complex sentence structures. Such non-semantic additions do what silent pauses and coughing can’t: they help the speaker speak and the listener listen. Similarly, the widely abhorred free-floating ‘like’ does not cut randomly into a ‘proper’ sentence but rather inserts itself, according to the logic of the language, either at the beginning of a sentence or before a verb, noun or adjective. It’s a form of ‘discourse marker’, used to ‘contribute to how we understand each other by providing clues to a speaker’s intentions’, writes Fridland. She points out that Shakespeare used discourse markers frequently, while the epic poem Beowulf begins with one (Hwæt!).

more here.

The Last Repair Shop

Tuesday, November 14, 2023

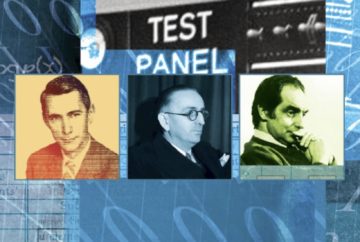

Language Machinery

Richard Hughes Gibson in The Hedgehog Review:

Consider a few of the bolder claims made by experts. Two years ago, Blaise Agüera y Arcas, vice president of Google Research, had already declared the end of the animal kingdom’s monopoly on language on the strength of Google’s experiments with large language models. LLMs, he argued, “illustrate for the first time the way that language understanding and intelligence can be dissociated from all the embodied and emotional characteristics we share with each other and with many other animals.” In a similar vein, the Stanford University computer scientist Christopher Manning has argued that if “meaning” constitutes “understanding of the network of connections between linguistic form and other things,” be they “objects in the world or other linguistic forms,” then “there can be no doubt” that LLMs can “learn meanings.” Again, the point is that humans have company. The philosopher Tobias Rees (among many others) has gone further, arguing that LLMs constitute a “far-reaching, epoch-making philosophical event” on par with the shift from the premodern conception of language as a divine gift to the modern notion of language as a distinctly human trait, even our defining one. On Rees’s telling, engineers at OpenAI, Google, and Facebook have become the new Descartes and Locke, “[rendering] untenable the idea that only humans have language” and thereby undermining the modern paradigm those philosophers inaugurated. LLMs, for Rees at least, signal modernity’s end.

Consider a few of the bolder claims made by experts. Two years ago, Blaise Agüera y Arcas, vice president of Google Research, had already declared the end of the animal kingdom’s monopoly on language on the strength of Google’s experiments with large language models. LLMs, he argued, “illustrate for the first time the way that language understanding and intelligence can be dissociated from all the embodied and emotional characteristics we share with each other and with many other animals.” In a similar vein, the Stanford University computer scientist Christopher Manning has argued that if “meaning” constitutes “understanding of the network of connections between linguistic form and other things,” be they “objects in the world or other linguistic forms,” then “there can be no doubt” that LLMs can “learn meanings.” Again, the point is that humans have company. The philosopher Tobias Rees (among many others) has gone further, arguing that LLMs constitute a “far-reaching, epoch-making philosophical event” on par with the shift from the premodern conception of language as a divine gift to the modern notion of language as a distinctly human trait, even our defining one. On Rees’s telling, engineers at OpenAI, Google, and Facebook have become the new Descartes and Locke, “[rendering] untenable the idea that only humans have language” and thereby undermining the modern paradigm those philosophers inaugurated. LLMs, for Rees at least, signal modernity’s end.

More here.

Bill Gates: AI is about to completely change how you use computers

Bill Gates in his blog, Gates Notes:

To do any task on a computer, you have to tell your device which app to use. You can use Microsoft Word and Google Docs to draft a business proposal, but they can’t help you send an email, share a selfie, analyze data, schedule a party, or buy movie tickets. And even the best sites have an incomplete understanding of your work, personal life, interests, and relationships and a limited ability to use this information to do things for you. That’s the kind of thing that is only possible today with another human being, like a close friend or personal assistant.

To do any task on a computer, you have to tell your device which app to use. You can use Microsoft Word and Google Docs to draft a business proposal, but they can’t help you send an email, share a selfie, analyze data, schedule a party, or buy movie tickets. And even the best sites have an incomplete understanding of your work, personal life, interests, and relationships and a limited ability to use this information to do things for you. That’s the kind of thing that is only possible today with another human being, like a close friend or personal assistant.

In the next five years, this will change completely. You won’t have to use different apps for different tasks. You’ll simply tell your device, in everyday language, what you want to do. And depending on how much information you choose to share with it, the software will be able to respond personally because it will have a rich understanding of your life. In the near future, anyone who’s online will be able to have a personal assistant powered by artificial intelligence that’s far beyond today’s technology.

This type of software—something that responds to natural language and can accomplish many different tasks based on its knowledge of the user—is called an agent.

More here.

‘Insanity’: petrostates planning huge expansion of fossil fuels, says UN report

Damian Carrington in The Guardian:

The world’s fossil fuel producers are planning expansions that would blow the planet’s carbon budget twice over, a UN report has found. Experts called the plans “insanity” which “throw humanity’s future into question”.

The world’s fossil fuel producers are planning expansions that would blow the planet’s carbon budget twice over, a UN report has found. Experts called the plans “insanity” which “throw humanity’s future into question”.

The energy plans of the petrostates contradicted their climate policies and pledges, the report said. The plans would lead to 460% more coal production, 83% more gas, and 29% more oil in 2030 than it was possible to burn if global temperature rise was to be kept to the internationally agreed 1.5C. The plans would also produce 69% more fossil fuels than is compatible with the riskier 2C target.

The countries responsible for the largest carbon emissions from planned fossil fuel production are India (coal), Saudi Arabia (oil) and Russia (coal, oil and gas). The US and Canada are also planning to be major oil producers, as is the United Arab Emirates. The UAE is hosting the crucial UN climate summit Cop28, which starts on 30 November.

More here.

Sabine Hossenfelder: The Net Zero Myth & Why Reaching our Climate Goals is Virtually Impossible

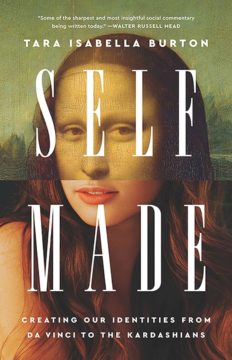

Have We Become Gods?

Brad East at Commonweal:

I am what I want, and I have the power within myself to make myself what I want to be, if only I find the will to activate this inner potential—or rather, to manifest this authentic identity. Such is the thesis under review in Tara Isabella Burton’s new book, Self-Made: Creating Our Identities from Da Vinci to the Kardashians. The thesis is not a new one. It has a long history, which, in Burton’s telling, begins around the fifteenth century. Though she finds its philosophical culmination in the eighteenth, with the Enlightenment, most of her story covers the past two hundred years: from bon ton and Beau Brummell to “the two most prominent self-creators of the past twenty years,” Kim Kardashian and Donald Trump. Across Western Europe and the Anglophone world, self-creation as both a transcendent possibility and a moral imperative trickles down to ordinary people’s lives and self-understanding, mutating in tandem with religious, economic, and technological changes. Since creation is traditionally the prerogative of deity, Burton’s story is ultimately about “how we became gods.”

I am what I want, and I have the power within myself to make myself what I want to be, if only I find the will to activate this inner potential—or rather, to manifest this authentic identity. Such is the thesis under review in Tara Isabella Burton’s new book, Self-Made: Creating Our Identities from Da Vinci to the Kardashians. The thesis is not a new one. It has a long history, which, in Burton’s telling, begins around the fifteenth century. Though she finds its philosophical culmination in the eighteenth, with the Enlightenment, most of her story covers the past two hundred years: from bon ton and Beau Brummell to “the two most prominent self-creators of the past twenty years,” Kim Kardashian and Donald Trump. Across Western Europe and the Anglophone world, self-creation as both a transcendent possibility and a moral imperative trickles down to ordinary people’s lives and self-understanding, mutating in tandem with religious, economic, and technological changes. Since creation is traditionally the prerogative of deity, Burton’s story is ultimately about “how we became gods.”

more here.