by Robert Fay

Near the end of Italy’s greatest 20th century novel, The Leopard by Giuseppe di Lampedusa, the elderly Prince Salinas is slumped in an armchair on a Sicilian hotel balcony looking at Mounte Pelligrino. The Prince knows he’s dying, but even more poignantly, he understands centuries of Salinas aristocratic mores and traditions will soon die with him. It is 1881 and a unified, republican Italy has recently displaced the monarchial customs and feudal relationships of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The Prince has witnessed the complete collapse of his world within two decades. And though he has an heir, his grandson Fabrizietto, the boy is “odious” and incapable of protecting the sacred Salinas patrimony. He is a product of this new, republican age, “with his good-time instincts, with his tendency to middle-class chic.”

Lampedusa’s narrator describes the Prince’s loss this way: “for the significance of a noble family lies entirely in its traditions, that is in its vital memories. And (the Prince) was the last to have any unusual memories, anything different from other families. Fabrizietto would have only banal ones like his schoolfellows, of snacks, of spiteful little jokes against teachers…”

Trying to elicit sympathy for elites is generally a fool’s errand, but Lampedusa is such a master, that any unprejudiced reader of The Leopard will surely be moved by the enormous humanity of the Prince. He is undoubtedly a snob, but his snobbery is like the egoism of a fighter pilot or the boastful pride of a mother, which is to say, it is in inseparable from their mission, their vocation. The power of this portrayal undoubtedly stems from the personal pain and loss in Lampedusa’s own life. He was born in 1896 to an aristocratic family and in 1943 his beloved family estate in Palermo—the seat of the Lampedusa family for centuries—was destroyed by U.S. Army Air Corps bombers during World War II. It was a loss that Lampedusa could never reconcile himself to. He had believed he’d die in that house, just as all ancestors had.

There is an echo of Lampadusa’s fate in the life of fellow aristocrat and novelist Vladimir Nabokov, who lost his ancestral estate(s) in Russia to war and politics. The Nabokovs had roots dating back to a 14th Century Tartar prince, but the cadres of the Bolshevik Revolution cut those ties in 1918, seizing the family’s properties and forcing them into exile. Nabokov never got over this loss. In a 1964 interview with Playboy he explained why he’d never bought a house in America, despite being a resident for 20 years, “…the background reason, is, I suppose, that nothing short of a replica of my childhood surroundings would have satisfied me. I would never manage to match my memories correctly—so why trouble with hopeless approximations?” Read more »

Our uniform was a shirt tucked into jeans. Sandi stretched the smallest size over well-proportioned breasts, her black bra peeking through a run of buttons. Mine hung long in the sleeves and fell over my waist.

Our uniform was a shirt tucked into jeans. Sandi stretched the smallest size over well-proportioned breasts, her black bra peeking through a run of buttons. Mine hung long in the sleeves and fell over my waist.

In the middle of the night of March 24, 1992, a pressure seal failed in the number three unit of the Leningradskaya Nuclear Power Plant at Sosnoviy Bor, Russia, releasing radioactive gases. With a friend, I had train tickets from Tallinn, in newly independent Estonia, to St. Petersburg the next day. That would take us within twenty kilometers of the plant. The legacy of Soviet management at Chernobyl a few years before set up a fraught decision whether or not to take the train.

In the middle of the night of March 24, 1992, a pressure seal failed in the number three unit of the Leningradskaya Nuclear Power Plant at Sosnoviy Bor, Russia, releasing radioactive gases. With a friend, I had train tickets from Tallinn, in newly independent Estonia, to St. Petersburg the next day. That would take us within twenty kilometers of the plant. The legacy of Soviet management at Chernobyl a few years before set up a fraught decision whether or not to take the train. Noam Chomsky was aptly described in a New York Times book review published almost four decades ago as “arguably the most important intellectual alive today.” He was 50 then. Now he is 90, and on the occasion of his December 7 birthday, the German international broadcasting service Deutsche Welle

Noam Chomsky was aptly described in a New York Times book review published almost four decades ago as “arguably the most important intellectual alive today.” He was 50 then. Now he is 90, and on the occasion of his December 7 birthday, the German international broadcasting service Deutsche Welle  In the spring of 2015, with my colleagues at the Breakthrough Institute, I helped to organize and publish

In the spring of 2015, with my colleagues at the Breakthrough Institute, I helped to organize and publish  Ivan Krastev’s last book landed like a warning shot on the desks of policymakers across the Continent. In his short 2017 volume, “After Europe,” the Bulgarian thinker warned that what had been until then widely regarded as a series of isolated shocks — the migration crisis, Brexit, the election of U.S. President Donald Trump, and the rise of

Ivan Krastev’s last book landed like a warning shot on the desks of policymakers across the Continent. In his short 2017 volume, “After Europe,” the Bulgarian thinker warned that what had been until then widely regarded as a series of isolated shocks — the migration crisis, Brexit, the election of U.S. President Donald Trump, and the rise of  You take a flight from New York to London. Thousands and perhaps millions of people — including ticket agents, baggage handlers, security personnel, air traffic controllers, pilots, and flight attendants, but behind the scenes also airline administrators, meteorologists, engineers, aircraft designers, and many others — cooperated to get you there safely. No one stole your luggage, no one ate your in-flight food, and no one tried to sit in your seat. In fact, the hundreds of people on the airplane, despite being mainly strangers, behaved in an entirely civilized and respectful manner throughout.

You take a flight from New York to London. Thousands and perhaps millions of people — including ticket agents, baggage handlers, security personnel, air traffic controllers, pilots, and flight attendants, but behind the scenes also airline administrators, meteorologists, engineers, aircraft designers, and many others — cooperated to get you there safely. No one stole your luggage, no one ate your in-flight food, and no one tried to sit in your seat. In fact, the hundreds of people on the airplane, despite being mainly strangers, behaved in an entirely civilized and respectful manner throughout. Here’s a little lesson about crying – historical crying – from another class I teach, “Literatures of American Indian Removal.” Once upon a time, the State of New Hampshire tried to claim Dartmouth College as its state university. In 1818, the case went to the Supreme Court, where John Marshall, as chief justice, presided. Dartmouth was represented by Daniel Webster. . . . It is, Sir, as I have said, a small college, and yet, there are those who love it . . . In an impassioned speech, Webster cited love as the private passion that draws a fairy circle of protection around the small college, keeping away publics that cannot possibly feel correctly. Webster’s oratory was so moving that the great judge wept openly on the bench. John Marshall, who shaped the Supreme Court into the powerful third arm of government that we now rely on it to be, was moved to tears. Dartmouth was founded to educate Native men, but immediately abandoned that project. That abandonment was partly why New Hampshire felt it could be claimed as public. But Marshall’s court decided it would remain private. The decision is a cornerstone of the American corporation. The corporation, he wrote, “is chiefly for the purpose of clothing bodies of men, in succession, with these qualities and capacities that corporations were invented, and are in use. By these means, a perpetual succession of individuals are capable of acting for the promotion of the particular object like one immortal being.” Corporations are immortal bodies, made up of successive generations of white men clothed in the invisibility cloak of power.

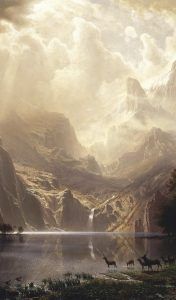

Here’s a little lesson about crying – historical crying – from another class I teach, “Literatures of American Indian Removal.” Once upon a time, the State of New Hampshire tried to claim Dartmouth College as its state university. In 1818, the case went to the Supreme Court, where John Marshall, as chief justice, presided. Dartmouth was represented by Daniel Webster. . . . It is, Sir, as I have said, a small college, and yet, there are those who love it . . . In an impassioned speech, Webster cited love as the private passion that draws a fairy circle of protection around the small college, keeping away publics that cannot possibly feel correctly. Webster’s oratory was so moving that the great judge wept openly on the bench. John Marshall, who shaped the Supreme Court into the powerful third arm of government that we now rely on it to be, was moved to tears. Dartmouth was founded to educate Native men, but immediately abandoned that project. That abandonment was partly why New Hampshire felt it could be claimed as public. But Marshall’s court decided it would remain private. The decision is a cornerstone of the American corporation. The corporation, he wrote, “is chiefly for the purpose of clothing bodies of men, in succession, with these qualities and capacities that corporations were invented, and are in use. By these means, a perpetual succession of individuals are capable of acting for the promotion of the particular object like one immortal being.” Corporations are immortal bodies, made up of successive generations of white men clothed in the invisibility cloak of power. Have you ever felt awe and exhilaration while contemplating a vista of jagged, snow-capped mountains? Or been fascinated but also a bit unsettled while beholding a thunderous waterfall such as Niagara? Or felt existentially insignificant but strangely exalted while gazing up at the clear, starry night sky? If so, then you’ve had an experience of what philosophers from the mid-18th century to the present call the sublime. It is an aesthetic experience that modern, Western philosophers often theorise about, as well as, more recently, experimental psychologists and neuroscientists in the field of

Have you ever felt awe and exhilaration while contemplating a vista of jagged, snow-capped mountains? Or been fascinated but also a bit unsettled while beholding a thunderous waterfall such as Niagara? Or felt existentially insignificant but strangely exalted while gazing up at the clear, starry night sky? If so, then you’ve had an experience of what philosophers from the mid-18th century to the present call the sublime. It is an aesthetic experience that modern, Western philosophers often theorise about, as well as, more recently, experimental psychologists and neuroscientists in the field of  In this series, economists debate whether catastrophic global warming can be stopped while maintaining current levels of economic growth. Enno Schröder, Servaas Storm, Gregor Semieniuk, Lance Taylor, and Armon Rezai find there is a tradeoff between growth and decarbonization, while Michael Grubb responds with more optimism.

In this series, economists debate whether catastrophic global warming can be stopped while maintaining current levels of economic growth. Enno Schröder, Servaas Storm, Gregor Semieniuk, Lance Taylor, and Armon Rezai find there is a tradeoff between growth and decarbonization, while Michael Grubb responds with more optimism.