Addressing The Flaxen Spirit & Linen Women

—Addressing the flaxen spirit, not yet linen

Threshing

We come from deep loam,

from fields of green, blue heads bobbing.

To harvest true selves and loosen seeds within,

permit wind to winnow away the clutter.

Retting

To release fiber from stem,

baptize in slow-moving waters,

or even dew.

Do not over-ret, for, as with anything,

there is danger of growing weak,

and breaking.

After the retting

the scutching begins.

Baptism is never enough.

To transform woody selves

to strands of silky smooth,

press against the sharp edge

of life. Prepare to spin

with the moaning

earth.

Heckling

is the hardest part,

but it must be done—

we must separate

from our selves

to be spun into one.

Be still and comb

the heart, untangle

worry, part from grudges,

brush away the last stray

residues of this hardened

life we cling to.

Nothing to weigh us down,

readied now,

to be woven. Read more »

‘I am glad,’ wrote the acclaimed American philosopher Susan Wolf, ‘that neither I nor those about whom I care most’ are ‘moral saints’. This declaration is one of the opening remarks of a landmark essay in which Wolf imagines what it would be like to be morally perfect. If you engage with Wolf’s thought experiment, and the conclusions she draws from it, then you will find that it offers liberation from the trap of moral perfection.

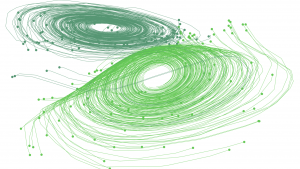

‘I am glad,’ wrote the acclaimed American philosopher Susan Wolf, ‘that neither I nor those about whom I care most’ are ‘moral saints’. This declaration is one of the opening remarks of a landmark essay in which Wolf imagines what it would be like to be morally perfect. If you engage with Wolf’s thought experiment, and the conclusions she draws from it, then you will find that it offers liberation from the trap of moral perfection. David Duvenaud was collaborating on a project involving medical data when he ran up against a major shortcoming in AI.

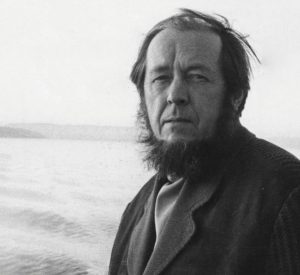

David Duvenaud was collaborating on a project involving medical data when he ran up against a major shortcoming in AI. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, pundits offered a variety of reasons for its failure: economic, political, military. Few thought to add a fourth, more elusive cause: the regime’s total loss of credibility.

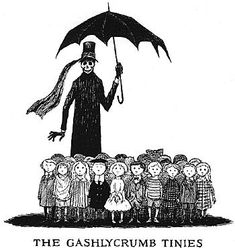

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, pundits offered a variety of reasons for its failure: economic, political, military. Few thought to add a fourth, more elusive cause: the regime’s total loss of credibility. Gorey has here and there been described as ‘Dr Seuss for Tim Burton fans’ and ‘the Charles Schulz of the macabre’, but he was in every way more wayward and interesting than that. He wrote almost impossible to classify little books — crunched-down Victorian novels — that seemed to belong in the children’s sections of bookshops but were quite unsuited to children, in whom he took little or no interest. He found a public only very slowly, and over many years — thanks, in large part, to till-point placement and Hello-Kitty-scale merchandising efforts by the Gotham Book Mart in New York.

Gorey has here and there been described as ‘Dr Seuss for Tim Burton fans’ and ‘the Charles Schulz of the macabre’, but he was in every way more wayward and interesting than that. He wrote almost impossible to classify little books — crunched-down Victorian novels — that seemed to belong in the children’s sections of bookshops but were quite unsuited to children, in whom he took little or no interest. He found a public only very slowly, and over many years — thanks, in large part, to till-point placement and Hello-Kitty-scale merchandising efforts by the Gotham Book Mart in New York. E

E

Minutes before stepping out into the spotlight on a stage – totally naked – I am wondering whether to wear socks. “It’s cold,” shivers another performer. A friend counsels, “If you’re going out naked, do it in full.” The matter of the sock is a distraction from the fact that we’re about to show our willies to the masses. This might not be Wembley Arena, but the trendy basement bar in east London I’m performing in is packed with people – mainly men. Anticipation crackles among them. They giggle about picking seats with a good view of the stage. There are twice as many eyeballs as people. And each one of them is about to see all I have.

Minutes before stepping out into the spotlight on a stage – totally naked – I am wondering whether to wear socks. “It’s cold,” shivers another performer. A friend counsels, “If you’re going out naked, do it in full.” The matter of the sock is a distraction from the fact that we’re about to show our willies to the masses. This might not be Wembley Arena, but the trendy basement bar in east London I’m performing in is packed with people – mainly men. Anticipation crackles among them. They giggle about picking seats with a good view of the stage. There are twice as many eyeballs as people. And each one of them is about to see all I have. Brain conditions such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder have long been known to have an inherited component, but pinpointing

Brain conditions such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder have long been known to have an inherited component, but pinpointing

As the bus nears downtown Katowice, the site of the 24th annual UN Climate Conference, or COP24, two huge funnels loom into view: a coal mine. There are fourteen in Katowice, although only two remain active. The rest lie strewn across the city like dormant volcanoes. The UN insists that Katowice is in transition—“from black to green,” says a welcome video at the opening ceremony—and claims that 40 percent of the city’s surface area is devoted to green spaces. Judging by the looks on their faces as they ogle the coal mine, the delegates on this bus do not see it that way. When they disembark, one of them scrunches up his nose at the unmistakable smell—rich and smoky—that wafts from an alleyway. Many Katowicians still burn coal for heat.

As the bus nears downtown Katowice, the site of the 24th annual UN Climate Conference, or COP24, two huge funnels loom into view: a coal mine. There are fourteen in Katowice, although only two remain active. The rest lie strewn across the city like dormant volcanoes. The UN insists that Katowice is in transition—“from black to green,” says a welcome video at the opening ceremony—and claims that 40 percent of the city’s surface area is devoted to green spaces. Judging by the looks on their faces as they ogle the coal mine, the delegates on this bus do not see it that way. When they disembark, one of them scrunches up his nose at the unmistakable smell—rich and smoky—that wafts from an alleyway. Many Katowicians still burn coal for heat. We made each other’s acquaintance among things and by way of them. Once again, I don’t remember anything about the subject of conversation: what I do remember is the perfect harmony the bread and wine afforded us. For instance, I could immediately see that you, Stravinsky, like me, love bread when it’s good and wine when it’s good, bread and wine together, each for the other, each through the other. This is where your personality and, by the same token, your art—in other words, all of you—begin; I took the outermost path to this inner knowledge, the most terrestrial road. There was no “artistic” or “aesthetic” discussion, if memory serves; but I can still see you smiling at your full glass, the bread you were brought, the carafe. I can see you picking up your knife and the quick, decisive gesture with which you separated the rind from the lovely semi-firm cheese. I came to know you amid and through the kind of pleasure I saw you derive from things, the so-called “humblest” ones; a certain brand and quality of delectation that gets the whole being interested. I love the body, as you know, because I can scarcely separate it from the soul; mostly I love the great unity of their total participation in such a maneuver, where the abstract and concrete find themselves reconciled, where they explain and elucidate one another. For many young ladies, a musician is a big forehead with “ideas” inside (God only knows which ones!): you showed me right away that the musician who invents a sound might be the furthest thing from a specialist, and that he distills it from a living substance, a substance common to all of us but with which one must first make direct and human contact.

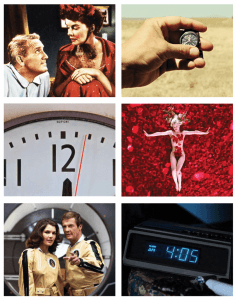

We made each other’s acquaintance among things and by way of them. Once again, I don’t remember anything about the subject of conversation: what I do remember is the perfect harmony the bread and wine afforded us. For instance, I could immediately see that you, Stravinsky, like me, love bread when it’s good and wine when it’s good, bread and wine together, each for the other, each through the other. This is where your personality and, by the same token, your art—in other words, all of you—begin; I took the outermost path to this inner knowledge, the most terrestrial road. There was no “artistic” or “aesthetic” discussion, if memory serves; but I can still see you smiling at your full glass, the bread you were brought, the carafe. I can see you picking up your knife and the quick, decisive gesture with which you separated the rind from the lovely semi-firm cheese. I came to know you amid and through the kind of pleasure I saw you derive from things, the so-called “humblest” ones; a certain brand and quality of delectation that gets the whole being interested. I love the body, as you know, because I can scarcely separate it from the soul; mostly I love the great unity of their total participation in such a maneuver, where the abstract and concrete find themselves reconciled, where they explain and elucidate one another. For many young ladies, a musician is a big forehead with “ideas” inside (God only knows which ones!): you showed me right away that the musician who invents a sound might be the furthest thing from a specialist, and that he distills it from a living substance, a substance common to all of us but with which one must first make direct and human contact. Between 2007 and 2010, the artist Christian Marclay and a team of researchers scoured tens of thousands of films for scenes and shots in which time was in some way incorporated. It could be a close-up of a watch or a sand timer, the $10m four-faced opal clock at New York Grand Central Station or a novelty timepiece showing two pigs humping merrily (from Mighty Aphrodite). Better yet, it might be an instance in which time plays a pivotal role: the clock tower struck by lightning in Back to the Future, or Harold Lloyd clinging to the minute hand high above Los Angeles in Safety Last!

Between 2007 and 2010, the artist Christian Marclay and a team of researchers scoured tens of thousands of films for scenes and shots in which time was in some way incorporated. It could be a close-up of a watch or a sand timer, the $10m four-faced opal clock at New York Grand Central Station or a novelty timepiece showing two pigs humping merrily (from Mighty Aphrodite). Better yet, it might be an instance in which time plays a pivotal role: the clock tower struck by lightning in Back to the Future, or Harold Lloyd clinging to the minute hand high above Los Angeles in Safety Last!

Author Hannah Lillith Assadi revels in the contradictions of her identity: She was born in the United States to a Jewish mother and a Palestinian father. Her debut novel, “Sonora,” is a paean to the vexing process of how a second-generation immigrant struggles to come to terms with herself and history. Israeli-American novelist and poet Moriel Rothman-Zecher explores similar themes in “Sadness Is a White Bird,” revealing the agonizing internal struggle of an American-Israeli man who cannot balance his friendship with two Palestinians and his enrollment in the Israeli army. Both are examples of Millennial writers with Israeli and Palestinian heritage living in the US who are forging novel perspectives on the conflict.

Author Hannah Lillith Assadi revels in the contradictions of her identity: She was born in the United States to a Jewish mother and a Palestinian father. Her debut novel, “Sonora,” is a paean to the vexing process of how a second-generation immigrant struggles to come to terms with herself and history. Israeli-American novelist and poet Moriel Rothman-Zecher explores similar themes in “Sadness Is a White Bird,” revealing the agonizing internal struggle of an American-Israeli man who cannot balance his friendship with two Palestinians and his enrollment in the Israeli army. Both are examples of Millennial writers with Israeli and Palestinian heritage living in the US who are forging novel perspectives on the conflict. Implanted electronics can steady hearts, calm tremors, and heal wounds—but at a cost. These machines are often large, obtrusive contraptions with batteries and wires, which require surgery to implant and sometimes need replacement. That’s changing.

Implanted electronics can steady hearts, calm tremors, and heal wounds—but at a cost. These machines are often large, obtrusive contraptions with batteries and wires, which require surgery to implant and sometimes need replacement. That’s changing.