Jonathan Malesic in The Hedgehog Review:

Two years ago, I gave an academic talk via Zoom on the need to limit work in order to combat the culture of burnout in the United States. Following my presentation, a senior scholar had more of a comment than a question for me. He said that “we” needed to acknowledge our privileged status among workers. When academics criticize the American work ethic, he added, we ought to recognize that most workers “can’t afford to burn out.” Burnout, I took him to be saying, was a luxury, and to complain about it was like flaunting your wealth before someone desperately poor.

Two years ago, I gave an academic talk via Zoom on the need to limit work in order to combat the culture of burnout in the United States. Following my presentation, a senior scholar had more of a comment than a question for me. He said that “we” needed to acknowledge our privileged status among workers. When academics criticize the American work ethic, he added, we ought to recognize that most workers “can’t afford to burn out.” Burnout, I took him to be saying, was a luxury, and to complain about it was like flaunting your wealth before someone desperately poor.

Standing in my living room in a sport coat and sandals, I argued in response that in my call for shorter hours and living wages, there was no competition between what was good for “us” and what was good for the custodians who cleaned university classrooms. Everyone is harmed by burnout culture, I maintained, and if everyone has equal dignity and therefore an equal right to a decent living, then everyone deserves better working conditions, regardless of the work they do.

More here.

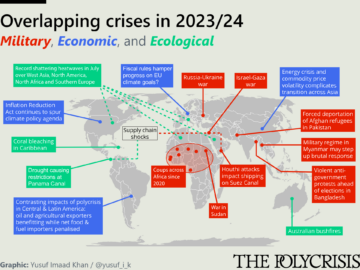

Tim Sahay in Polycrisis:

Tim Sahay in Polycrisis: I HAVE FREQUENTLY BEEN SEATED in the dark near those who have variously been called “the pilly-sweater crowd,” “cinemaniacs,” or “Titus-heads” (referring to the two main movie theaters at MoMA). They are pejorative terms for a certain type of New York City cinephile, one whose zeal for the seventh art seems to have been leached of all pleasure and has instead transmogrified into grim compulsion. Demographically, they are often (but not always) white, male, and middle-aged or older.

I HAVE FREQUENTLY BEEN SEATED in the dark near those who have variously been called “the pilly-sweater crowd,” “cinemaniacs,” or “Titus-heads” (referring to the two main movie theaters at MoMA). They are pejorative terms for a certain type of New York City cinephile, one whose zeal for the seventh art seems to have been leached of all pleasure and has instead transmogrified into grim compulsion. Demographically, they are often (but not always) white, male, and middle-aged or older. A

A I

I Ernest Becker was already dying when “The Denial of Death” was published 50 years ago this past fall. “This is a test of everything I’ve written about death,” he told a visitor to his Vancouver hospital room. Throughout his career as a cultural anthropologist, Becker had charted the undiscovered country that awaits us all. Now only 49 but losing a battle to colon cancer, he was being dispatched there himself. By the time his book was

Ernest Becker was already dying when “The Denial of Death” was published 50 years ago this past fall. “This is a test of everything I’ve written about death,” he told a visitor to his Vancouver hospital room. Throughout his career as a cultural anthropologist, Becker had charted the undiscovered country that awaits us all. Now only 49 but losing a battle to colon cancer, he was being dispatched there himself. By the time his book was  The emergence of English as the predominant (though not exclusive) international language is seen by many as a positive phenomenon with several practical advantages and no downside. However, it also raises problems that are slowly beginning to be understood and studied.

The emergence of English as the predominant (though not exclusive) international language is seen by many as a positive phenomenon with several practical advantages and no downside. However, it also raises problems that are slowly beginning to be understood and studied. Some say that history begins with writing; we say that history begins with clothing. In the beginning, there was clothing made from skins that early humans removed from animals, processed, and then tailored to fit the human body; this technique is still used in the Arctic. Next came textiles. The first weavers would weave textiles in the shape of animal hides or raise the nap of the fabric’s surface to mimic the appearance of fur, making the fabric warmer and more comfortable.

Some say that history begins with writing; we say that history begins with clothing. In the beginning, there was clothing made from skins that early humans removed from animals, processed, and then tailored to fit the human body; this technique is still used in the Arctic. Next came textiles. The first weavers would weave textiles in the shape of animal hides or raise the nap of the fabric’s surface to mimic the appearance of fur, making the fabric warmer and more comfortable. This was during the Long 2010s (2009-2022), a decade during which there occurred more mass protests than any decade in history. The protests were against the usual suspects: capitalism, racism, imperialism, greed, corruption. Two new books, Vincent Bevins’s If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution and The Populist Moment: The Left After the Great Recession by Arthur Borriello and Anton Jäger, are about these protests and why they seemed to summon more of what they protested against—more greed, more racism, more corruption. They take different approaches. The Populist Moment is an academic investigation into the electoral failures of left-wing candidates in Europe and the United States (Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn, Jean-Luc Melenchon, Greece’s Syriza party), while If We Burn is a journalistic account of street protests in the Third World (Brazil, Indonesia, Chile) as well as Turkey and Ukraine.

This was during the Long 2010s (2009-2022), a decade during which there occurred more mass protests than any decade in history. The protests were against the usual suspects: capitalism, racism, imperialism, greed, corruption. Two new books, Vincent Bevins’s If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution and The Populist Moment: The Left After the Great Recession by Arthur Borriello and Anton Jäger, are about these protests and why they seemed to summon more of what they protested against—more greed, more racism, more corruption. They take different approaches. The Populist Moment is an academic investigation into the electoral failures of left-wing candidates in Europe and the United States (Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn, Jean-Luc Melenchon, Greece’s Syriza party), while If We Burn is a journalistic account of street protests in the Third World (Brazil, Indonesia, Chile) as well as Turkey and Ukraine.