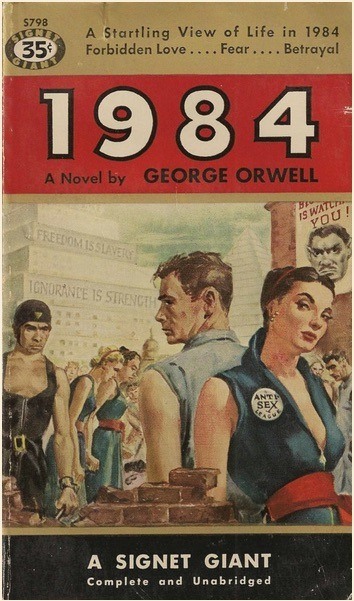

I first found Freud in the basement of the house on Luther Road. There was a small closet in the corner and my father had a box or two of paperback books in it. I don’t remember but a few titles; in fact, I’m only sure of two: Wodehouse on Golf, which I never read, and 1984, which I most certainly did read, as it had a pulpy cover that promised sex – a buxom brunette in a tight blue jumpsuit emblazoned with “Women’s Anti-Sex League” – in THAT costume! Of course, the book wasn’t quite what the cover advertised, but that was OK. I may also have found Brave New World there, I’m not sure. Come to think of it though, that probably IS where I found War of the Worlds. So that’s three titles I’m pretty sure of.

I probably found some Bertrand Russell, too, though just exactly what, I can’t recall. I went on to buy a bunch of Russell, including his history of Western philosophy. I also found something by Theodore Reik (Listening with the Third Ear?), and went on to buy more of THAT. And I found Freud, perhaps Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality; after all, it has that magic word in the title: S E X.

In the summer between my freshman and sophomore years at Johns Hopkins I read The Interpretation of Dreams. Somewhere in there I picked up a five-volume set of The Collected Papers from a book club. I’ve still got them, though they’re in storage along with some other Freud. But I’ve still got Totem and Taboo, Civilization and It’s Discontents, and The Future of an Illusion on the shelves in my apartment. They’re slender volumes and so don’t take up much space and Civilization plays to my interest in cultural evolution. Read more »

Of all the internet’s uses, attractions and conveniences, the foremost is that it involves us immediately with an indefinite number of others. Its decisive edge over television and the printed word is just this: its participatory, social character. To the extent that it is becoming our chief means of private and public discourse, it is therefore acquiring exceptional political significance. To someone who understood nothing of the internet, much of contemporary American political life would be inscrutable. It is now our primary way of dealing with each other, our most important organ of collective speech and self-knowledge. The internet is, in this way, inherently recasting our wider notions of what to say, who to be, what to count as authoritative, and how to govern and be governed. What follows are some lines of thought sketching each of these transformations in turn.

Of all the internet’s uses, attractions and conveniences, the foremost is that it involves us immediately with an indefinite number of others. Its decisive edge over television and the printed word is just this: its participatory, social character. To the extent that it is becoming our chief means of private and public discourse, it is therefore acquiring exceptional political significance. To someone who understood nothing of the internet, much of contemporary American political life would be inscrutable. It is now our primary way of dealing with each other, our most important organ of collective speech and self-knowledge. The internet is, in this way, inherently recasting our wider notions of what to say, who to be, what to count as authoritative, and how to govern and be governed. What follows are some lines of thought sketching each of these transformations in turn. Robots that are self-aware have been science fiction fodder for decades, and now we may finally be getting closer. Humans are unique in being able to imagine themselves—to picture themselves in future scenarios, such as walking along the beach on a warm sunny day. Humans can also learn by revisiting past experiences and reflecting on what went right or wrong. While humans and animals acquire and adapt their self-image over their lifetime, most robots still learn using human-provided simulators and models, or by laborious, time-consuming trial and error. Robots have not learned simulate themselves the way humans do.

Robots that are self-aware have been science fiction fodder for decades, and now we may finally be getting closer. Humans are unique in being able to imagine themselves—to picture themselves in future scenarios, such as walking along the beach on a warm sunny day. Humans can also learn by revisiting past experiences and reflecting on what went right or wrong. While humans and animals acquire and adapt their self-image over their lifetime, most robots still learn using human-provided simulators and models, or by laborious, time-consuming trial and error. Robots have not learned simulate themselves the way humans do. Richard Feloni: What does Davos stand for in your view? Do you have any particular thoughts on this year’s, specifically?

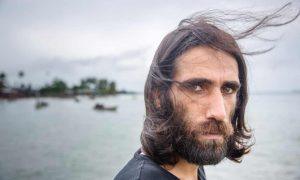

Richard Feloni: What does Davos stand for in your view? Do you have any particular thoughts on this year’s, specifically? The winner of Australia’s richest literary prize did not attend the ceremony.

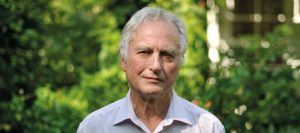

The winner of Australia’s richest literary prize did not attend the ceremony. In the digital age, reputations made over decades can be lost in minutes. Richard Dawkins first achieved renown as a pioneering evolutionary biologist (through his 1976 bestseller, The Selfish Gene) and, later, as a polemical foe of religion (through 2006’s The God Delusion). Yet he is now increasingly defined by his incendiary tweets, which have been plausibly denounced as Islamophobic.

In the digital age, reputations made over decades can be lost in minutes. Richard Dawkins first achieved renown as a pioneering evolutionary biologist (through his 1976 bestseller, The Selfish Gene) and, later, as a polemical foe of religion (through 2006’s The God Delusion). Yet he is now increasingly defined by his incendiary tweets, which have been plausibly denounced as Islamophobic. Michael Jordan,

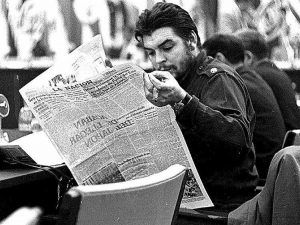

Michael Jordan,  Even Che Guevara, the poster boy for the Cuban Revolution, was forced to admit that endlessly trudging the Sierra Maestra mountains had its downsides. “There are periods of boredom in the life of the guerrilla fighter,” he warns future revolutionaries in his classic handbook, Guerrilla Warfare. The best way to combat the dangers of ennui, he helpfully suggests, is reading. Many of the rebels were college educated—Che was a doctor, Fidel a lawyer, others fine art majors—and visitors to the rebels’ jungle camps were often struck by their literary leanings. Even the most macho fighters, it seems, would be seen hunched over books.

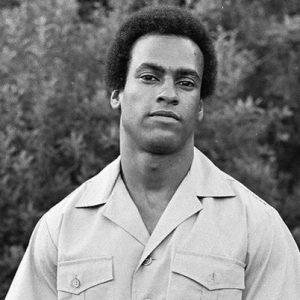

Even Che Guevara, the poster boy for the Cuban Revolution, was forced to admit that endlessly trudging the Sierra Maestra mountains had its downsides. “There are periods of boredom in the life of the guerrilla fighter,” he warns future revolutionaries in his classic handbook, Guerrilla Warfare. The best way to combat the dangers of ennui, he helpfully suggests, is reading. Many of the rebels were college educated—Che was a doctor, Fidel a lawyer, others fine art majors—and visitors to the rebels’ jungle camps were often struck by their literary leanings. Even the most macho fighters, it seems, would be seen hunched over books. On August 15, 1970, Huey P. Newton, the co-founder of the Black Panther Party, gave a speech in New York City where he outlined the Party’s position on two emerging movements at the time, the women’s liberation movement and the gay liberation movement. Newton’s remarks were strikingly unusual since most conservative, moderate, and radical black organizations remained silent on the issues addressed by these movements. The speech appears below.

On August 15, 1970, Huey P. Newton, the co-founder of the Black Panther Party, gave a speech in New York City where he outlined the Party’s position on two emerging movements at the time, the women’s liberation movement and the gay liberation movement. Newton’s remarks were strikingly unusual since most conservative, moderate, and radical black organizations remained silent on the issues addressed by these movements. The speech appears below. John McGahern and Annie Proulx are among my favourite authors, but to dispel gloom I choose this story from Jane Gardam’s 1980 collection The Sidmouth Letters. Reading this gleeful story in my expatriate days, I recognised the cast of “diplomatic wives”, trailing inebriate husbands through the ruins of empire. Mostly dialogue, it is a deft, witty tale in which a small kindness – though not by a diplomatic wife – pays off 40 years later. I must have read it a dozen times, to see how its note is sustained and the surprise is sprung; every time it makes me smile with delight. Hilary Mantel

John McGahern and Annie Proulx are among my favourite authors, but to dispel gloom I choose this story from Jane Gardam’s 1980 collection The Sidmouth Letters. Reading this gleeful story in my expatriate days, I recognised the cast of “diplomatic wives”, trailing inebriate husbands through the ruins of empire. Mostly dialogue, it is a deft, witty tale in which a small kindness – though not by a diplomatic wife – pays off 40 years later. I must have read it a dozen times, to see how its note is sustained and the surprise is sprung; every time it makes me smile with delight. Hilary Mantel On a Monday afternoon in December, Sarah Jones, a Tony award-winning playwright and impressionist, sits at a flimsy metal table in Los Angeles’s Grand Central Market, a cavernous food hall hawking a vast array of cuisine: grass-fed lamb, vegan ramen, tacos, acai bowls. Around her, scruffy workers in baseball caps take their lunches next to corporate types in suits. In a city where the car culture promotes a gas-guzzling form of isolation, the market offers an alternative atmosphere: it buzzes with the energy of happenstance meetings.

On a Monday afternoon in December, Sarah Jones, a Tony award-winning playwright and impressionist, sits at a flimsy metal table in Los Angeles’s Grand Central Market, a cavernous food hall hawking a vast array of cuisine: grass-fed lamb, vegan ramen, tacos, acai bowls. Around her, scruffy workers in baseball caps take their lunches next to corporate types in suits. In a city where the car culture promotes a gas-guzzling form of isolation, the market offers an alternative atmosphere: it buzzes with the energy of happenstance meetings. Argentinian artist Mirtha Dermisache produced “a voluminous body of illegible writings.” This phrase from the editors’ brief afterward is in itself so evocative I can hardly go further, that body light and aloft, setting sail on an invisible current of the thoughts beneath words, the feelings beneath skin.

Argentinian artist Mirtha Dermisache produced “a voluminous body of illegible writings.” This phrase from the editors’ brief afterward is in itself so evocative I can hardly go further, that body light and aloft, setting sail on an invisible current of the thoughts beneath words, the feelings beneath skin. Certainly, even as Cunard’s own work – long overlooked in favour of works about her, including a number of biographies – has recently begun to be recognized and republished, attention has still tended to focus on those of her writings with links to the more outré figures and avant-garde aesthetics of the 1920s. Of her poetry, it is the long Parallax (1925), a response to The Waste Land (and, like T. S. Eliot’s poem, published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press), that is best known – only partly because it is her best. Meanwhile, her prose, which includes extensive political journalism and several works of memoir, remains largely out of print, and her extensive career as an anti-fascist, anti-racist, and anti-imperial writer and activist is often characterized as a series of dilettantish enthusiasms.

Certainly, even as Cunard’s own work – long overlooked in favour of works about her, including a number of biographies – has recently begun to be recognized and republished, attention has still tended to focus on those of her writings with links to the more outré figures and avant-garde aesthetics of the 1920s. Of her poetry, it is the long Parallax (1925), a response to The Waste Land (and, like T. S. Eliot’s poem, published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press), that is best known – only partly because it is her best. Meanwhile, her prose, which includes extensive political journalism and several works of memoir, remains largely out of print, and her extensive career as an anti-fascist, anti-racist, and anti-imperial writer and activist is often characterized as a series of dilettantish enthusiasms.