Tony Perrottet in The Paris Review:

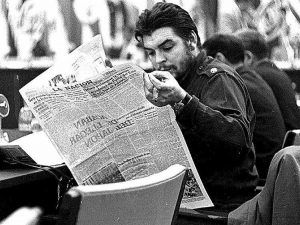

Even Che Guevara, the poster boy for the Cuban Revolution, was forced to admit that endlessly trudging the Sierra Maestra mountains had its downsides. “There are periods of boredom in the life of the guerrilla fighter,” he warns future revolutionaries in his classic handbook, Guerrilla Warfare. The best way to combat the dangers of ennui, he helpfully suggests, is reading. Many of the rebels were college educated—Che was a doctor, Fidel a lawyer, others fine art majors—and visitors to the rebels’ jungle camps were often struck by their literary leanings. Even the most macho fighters, it seems, would be seen hunched over books.

Even Che Guevara, the poster boy for the Cuban Revolution, was forced to admit that endlessly trudging the Sierra Maestra mountains had its downsides. “There are periods of boredom in the life of the guerrilla fighter,” he warns future revolutionaries in his classic handbook, Guerrilla Warfare. The best way to combat the dangers of ennui, he helpfully suggests, is reading. Many of the rebels were college educated—Che was a doctor, Fidel a lawyer, others fine art majors—and visitors to the rebels’ jungle camps were often struck by their literary leanings. Even the most macho fighters, it seems, would be seen hunched over books.

Che recommends that guerrillas carry edifying works of nonfiction despite their annoying weight—“good biographies of past heroes, histories, or economic geographies” will distract them from vices such as gambling and drinking. An early favorite in camp, improbably, was a Spanish-language Reader’s Digest book on great men in U.S. history, which the visiting CBS-TV journalist Robert Taber noticed in 1957 was passed around from man to man, possibly for his benefit. But literary fiction had its place, especially if it fit vaguely into the revolutionary framework. One big hit was Curzio Malaparte’s The Skin, a novel recounting the brutality of the occupation of Naples after World War II. (Ever convinced of victory, Fidel thought reading the book would help ensure that the men would behave well when they captured Havana.) More improbably, a dog-eared copy of Émile Zola’s psychological thriller The Beast Within was also pored over with an intensity that could only impress modern bibliophiles.

More here.