Paul Broks at Literary Review:

Madness is deep-rooted in the human imagination. The mad are unreachable, unfathomable, alarmingly other. They unsettle us. Yet we also romanticise madness. Great poetry and art spring from transcendent states at the edge of sanity, don’t they? And falling in love is a kind of madness, a stumbling into a dream world of irrationality and delusion. The lunatic, the lover and the poet are of imagination all compact. One line of thought is that madness is the price Homo sapiens has paid for the jewel of human consciousness. Perhaps it is.

Madness is deep-rooted in the human imagination. The mad are unreachable, unfathomable, alarmingly other. They unsettle us. Yet we also romanticise madness. Great poetry and art spring from transcendent states at the edge of sanity, don’t they? And falling in love is a kind of madness, a stumbling into a dream world of irrationality and delusion. The lunatic, the lover and the poet are of imagination all compact. One line of thought is that madness is the price Homo sapiens has paid for the jewel of human consciousness. Perhaps it is.

There have always been alienated individuals marked out as ‘mad’ by the rest of society on account of their bizarre beliefs and eccentric behaviour, but it was not until the late 19th century that Emil Kraepelin established a formal taxonomy of signs and symptoms.

more here.

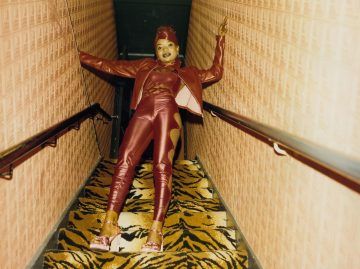

There is so much sound, movement, and energy in Liz Johnson Artur’s first solo museum show, “Dusha,” at the Brooklyn Museum, that walking through the galleries feels like attending a party at a local Pan-African community center. The exhibit showcases Artur’s “Black Balloon Archive,” which consists of images of the global African diaspora captured in the course of decades. Here are two boys spinning each other on the sidewalk, surrounded by a crowd of onlookers. Nearby is Brother Michael, in a black suit and white tie, selling Nation of Islam newspapers. A group of women show off their matching head wraps, and precocious schoolgirls relax outside a classroom. A man wearing Ankara prints and sunglasses mugs for the camera. All that is missing is the line for jollof and the music of Fela Kuti.

There is so much sound, movement, and energy in Liz Johnson Artur’s first solo museum show, “Dusha,” at the Brooklyn Museum, that walking through the galleries feels like attending a party at a local Pan-African community center. The exhibit showcases Artur’s “Black Balloon Archive,” which consists of images of the global African diaspora captured in the course of decades. Here are two boys spinning each other on the sidewalk, surrounded by a crowd of onlookers. Nearby is Brother Michael, in a black suit and white tie, selling Nation of Islam newspapers. A group of women show off their matching head wraps, and precocious schoolgirls relax outside a classroom. A man wearing Ankara prints and sunglasses mugs for the camera. All that is missing is the line for jollof and the music of Fela Kuti. With its gold-striped spine, crimson endpapers and silky leaves, My Seditious Heart is a handsome edition of previously published essays by Booker-winning writer

With its gold-striped spine, crimson endpapers and silky leaves, My Seditious Heart is a handsome edition of previously published essays by Booker-winning writer  Precision medicine flips the script on conventional medicine, which typically offers blanket recommendations and prescribes treatments designed to help more people than they harm but that might not work for you. The approach recognizes that we each possess distinct molecular characteristics, and they have an outsize impact on our health. Around the world, researchers are creating precision tools unimaginable just a decade ago: superfast DNA sequencing, tissue engineering, cellular reprogramming, gene editing, and more. The science and technology soon will make it feasible to predict your risk of cancer, heart disease, and countless other ailments years before you get sick. The work also offers prospects—tantalizing or unnerving, depending on your point of view—for altering genes in embryos and eliminating inherited diseases.

Precision medicine flips the script on conventional medicine, which typically offers blanket recommendations and prescribes treatments designed to help more people than they harm but that might not work for you. The approach recognizes that we each possess distinct molecular characteristics, and they have an outsize impact on our health. Around the world, researchers are creating precision tools unimaginable just a decade ago: superfast DNA sequencing, tissue engineering, cellular reprogramming, gene editing, and more. The science and technology soon will make it feasible to predict your risk of cancer, heart disease, and countless other ailments years before you get sick. The work also offers prospects—tantalizing or unnerving, depending on your point of view—for altering genes in embryos and eliminating inherited diseases. President Trump is now calling for expanding the death penalty so it would apply to drug dealers and those who kill police officers, with an expedited trial and quick execution. A majority of Americans (56 percent,

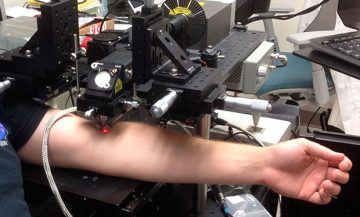

President Trump is now calling for expanding the death penalty so it would apply to drug dealers and those who kill police officers, with an expedited trial and quick execution. A majority of Americans (56 percent, Tumor cells that spread cancer via the bloodstream face a new foe: a laser beam, shined from outside the skin, that finds and kills these metastatic little demons on the spot.

Tumor cells that spread cancer via the bloodstream face a new foe: a laser beam, shined from outside the skin, that finds and kills these metastatic little demons on the spot. On July

On July Across the continent, many had anticipated further gains for far-right parties that masquerade in populism but spit raw racism. Thankfully, the so-called populist surge has been halted for the moment.

Across the continent, many had anticipated further gains for far-right parties that masquerade in populism but spit raw racism. Thankfully, the so-called populist surge has been halted for the moment.

I’m a comedy critic, so being a dad can seem like an occupational hazard. It may be professional suicide to admit, but since having children, I often find myself making lame puns as well as poop jokes. In subway stations, I have been known to silently mouth words to my daughters when a loud train goes by until the noise quiets and I add: “ … and that’s the secret to life.” Look, I’m not proud. The demise of a dad’s sense of humor begins in early parenthood while workshopping jokes in front of babies, tiny philistines who think peekaboo is a hilarious bit of misdirection. It isn’t long before these drooling rubes turn into trash-talking toddlers and fall in love with the scatological. Like so many lazy comics, we parents pander. If jokes work, they stay in the set. Gradually, we become hooked on cheap laughs. Some of us even delude ourselves into thinking we are actually funny.

I’m a comedy critic, so being a dad can seem like an occupational hazard. It may be professional suicide to admit, but since having children, I often find myself making lame puns as well as poop jokes. In subway stations, I have been known to silently mouth words to my daughters when a loud train goes by until the noise quiets and I add: “ … and that’s the secret to life.” Look, I’m not proud. The demise of a dad’s sense of humor begins in early parenthood while workshopping jokes in front of babies, tiny philistines who think peekaboo is a hilarious bit of misdirection. It isn’t long before these drooling rubes turn into trash-talking toddlers and fall in love with the scatological. Like so many lazy comics, we parents pander. If jokes work, they stay in the set. Gradually, we become hooked on cheap laughs. Some of us even delude ourselves into thinking we are actually funny. Alice Whittenburg in 3:AM Magazine:

Alice Whittenburg in 3:AM Magazine: Evgeny Morozov in The Guardian:

Evgeny Morozov in The Guardian: Rana Foroohar in the FT:

Rana Foroohar in the FT: Nick Hanauer in The Atlantic:

Nick Hanauer in The Atlantic: Suketu Mehta traveled the same route five times. As a child, he settled with his family, originally from Gujarat in India, in the United States. As an adult, he returned to India, where he lived in Mumbai (Bombay) for two and a half years and wrote a book about the city. Titled Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found and published in 2004, it was a highly acclaimed work that I can’t recommend enough. Mehta later returned to the United States, only to retrace his footsteps years later – but this time in his reminisces and feelings – in a new book, where he returns to the memories of his family voyage, to the story of how they, like so many others, moved to America, the promised land of generations of migrants. The second part of the title of Mehta’s new work says it all — This Land is Our Land: An Immigrant’s Manifesto. It is a powerful defense of people’s right to migrate, a song of praise for multiculturalism, and a strong critique of Washington’s policies toward immigrants and refugees under President Donald Trump. The author took pains to travel and collect various stories of migration – he took these pains quite literally, as a large part of the book is a cataloging of sorrows that people shared with him. Focusing mainly on the United States as a destination country, he provides statistics and cases to show where and how migration policies are failing. Mehta wrestles with the exorbitant fears of the “Other,” with the myth that the influx of migrants will sweep the country away.

Suketu Mehta traveled the same route five times. As a child, he settled with his family, originally from Gujarat in India, in the United States. As an adult, he returned to India, where he lived in Mumbai (Bombay) for two and a half years and wrote a book about the city. Titled Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found and published in 2004, it was a highly acclaimed work that I can’t recommend enough. Mehta later returned to the United States, only to retrace his footsteps years later – but this time in his reminisces and feelings – in a new book, where he returns to the memories of his family voyage, to the story of how they, like so many others, moved to America, the promised land of generations of migrants. The second part of the title of Mehta’s new work says it all — This Land is Our Land: An Immigrant’s Manifesto. It is a powerful defense of people’s right to migrate, a song of praise for multiculturalism, and a strong critique of Washington’s policies toward immigrants and refugees under President Donald Trump. The author took pains to travel and collect various stories of migration – he took these pains quite literally, as a large part of the book is a cataloging of sorrows that people shared with him. Focusing mainly on the United States as a destination country, he provides statistics and cases to show where and how migration policies are failing. Mehta wrestles with the exorbitant fears of the “Other,” with the myth that the influx of migrants will sweep the country away. To Kill a Mockingbird is a drama of white nobility in a white context, in which educated white people struggle decorously for black rights against the dangerous unreasonableness of uneducated white people. In one of the many passages in which Lee uses Atticus’ conversations with his children, Jem and Scout (the narrator of the novel) as Socratic expositions of the problems with the 1930s justice system, Jem asks this question: “why don’t people like us and Miss Maudie ever sit on juries? You never see anybody from Maycomb on a jury—they all come from out in the woods.” Jem is philosophically ready to abolish juries altogether. Atticus doesn’t put up much of an argument for why juries are necessary, saying only, “You’re rather hard on us, son” — meaning, presumably, that democracy has its good points too. Instead, Atticus offers a different solution: “I think there might be a better way. Change the law. Change it so that only judges have the power of fixing the penalty in capital cases.”

To Kill a Mockingbird is a drama of white nobility in a white context, in which educated white people struggle decorously for black rights against the dangerous unreasonableness of uneducated white people. In one of the many passages in which Lee uses Atticus’ conversations with his children, Jem and Scout (the narrator of the novel) as Socratic expositions of the problems with the 1930s justice system, Jem asks this question: “why don’t people like us and Miss Maudie ever sit on juries? You never see anybody from Maycomb on a jury—they all come from out in the woods.” Jem is philosophically ready to abolish juries altogether. Atticus doesn’t put up much of an argument for why juries are necessary, saying only, “You’re rather hard on us, son” — meaning, presumably, that democracy has its good points too. Instead, Atticus offers a different solution: “I think there might be a better way. Change the law. Change it so that only judges have the power of fixing the penalty in capital cases.” I first read “

I first read “