Binyamin Appelbaum in the New York Times:

In the early 1950s, a young economist named Paul Volcker worked as a human calculator in an office deep inside the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. He crunched numbers for the people who made decisions, and he told his wife that he saw little chance of ever moving up. The central bank’s leadership included bankers, lawyers and an Iowa hog farmer, but not a single economist. The Fed’s chairman, a former stockbroker named William McChesney Martin, once told a visitor that he kept a small staff of economists in the basement of the Fed’s Washington headquarters. They were in the building, he said, because they asked good questions. They were in the basement because “they don’t know their own limitations.”

In the early 1950s, a young economist named Paul Volcker worked as a human calculator in an office deep inside the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. He crunched numbers for the people who made decisions, and he told his wife that he saw little chance of ever moving up. The central bank’s leadership included bankers, lawyers and an Iowa hog farmer, but not a single economist. The Fed’s chairman, a former stockbroker named William McChesney Martin, once told a visitor that he kept a small staff of economists in the basement of the Fed’s Washington headquarters. They were in the building, he said, because they asked good questions. They were in the basement because “they don’t know their own limitations.”

Martin’s distaste for economists was widely shared among the midcentury American elite. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt dismissed John Maynard Keynes, the most important economist of his generation, as an impractical “mathematician.” President Eisenhower, in his farewell address, urged Americans to keep technocrats from power. Congress rarely consulted economists; regulatory agencies were led and staffed by lawyers; courts wrote off economic evidence as irrelevant.

But a revolution was coming.

More here.

To read Käsebier Takes Berlin today, more than 80 years after its original publication, is to experience occasional shocks of recognition. Many have noted the similarities between Weimar-era Germany and the Trump-era United States, and in Käsebier, these parallels sometimes come to the fore. As Duvernoy notes in her introduction, the rise of Käsebier is, in effect, the result of a story gone viral. In one passage, we come across the phrase “fake news.” In another, Miermann expresses something similar to the news fatigue so many Americans feel: “I’m always supposed to get worked up: against sales taxes, for sales taxes, against excise taxes, for excise taxes. I’m not going to get worked up again until five o’clock tomorrow unless a beautiful girl walks into the room!”

To read Käsebier Takes Berlin today, more than 80 years after its original publication, is to experience occasional shocks of recognition. Many have noted the similarities between Weimar-era Germany and the Trump-era United States, and in Käsebier, these parallels sometimes come to the fore. As Duvernoy notes in her introduction, the rise of Käsebier is, in effect, the result of a story gone viral. In one passage, we come across the phrase “fake news.” In another, Miermann expresses something similar to the news fatigue so many Americans feel: “I’m always supposed to get worked up: against sales taxes, for sales taxes, against excise taxes, for excise taxes. I’m not going to get worked up again until five o’clock tomorrow unless a beautiful girl walks into the room!” Baths are very comforting: gentler, calmer than showers. The slow clean. For a while, though, across a patch of nervous books in the mid-twentieth century, baths were troublesome. They were prone to intrusion and disorder. They were too hot, too small, too crowded with litanies of junk: newspapers, cigarettes, alcohol, razors.

Baths are very comforting: gentler, calmer than showers. The slow clean. For a while, though, across a patch of nervous books in the mid-twentieth century, baths were troublesome. They were prone to intrusion and disorder. They were too hot, too small, too crowded with litanies of junk: newspapers, cigarettes, alcohol, razors. The great service done by Mitchell Zuckoff in Fall and Rise is to document in minute but telling detail the innumerable human tragedies that unfolded in the space of a few hours on the morning of 11 September 2001.

The great service done by Mitchell Zuckoff in Fall and Rise is to document in minute but telling detail the innumerable human tragedies that unfolded in the space of a few hours on the morning of 11 September 2001. In November 1959 aged 26,

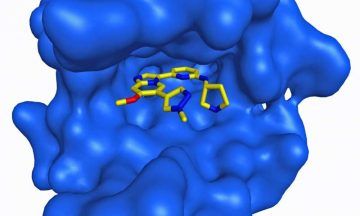

In November 1959 aged 26,  Scientists from the National Institutes of Health and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center have devised a potential treatment against a common type of leukemia that could have implications for many other types of cancer. The new approach takes aim at a way that cancer cells evade the effects of drugs, a process called adaptive resistance. The researchers, in a range of studies, identified a cellular pathway that allows a form of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a deadly blood and bone marrow

Scientists from the National Institutes of Health and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center have devised a potential treatment against a common type of leukemia that could have implications for many other types of cancer. The new approach takes aim at a way that cancer cells evade the effects of drugs, a process called adaptive resistance. The researchers, in a range of studies, identified a cellular pathway that allows a form of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a deadly blood and bone marrow  Mario Seccareccia and Marc Lavoie over at INET:

Mario Seccareccia and Marc Lavoie over at INET:

The people of Jammu and Kashmir on both sides of the border have been continuously betrayed by the governments of Pakistan and India.

The people of Jammu and Kashmir on both sides of the border have been continuously betrayed by the governments of Pakistan and India. Last night I was talking with our mutual friend S, and she said, “I always wanted to hear what Ann would say. She would listen to others present arguments, and then, when it was her turn to speak, she would find the beautiful bits in what she’d heard and put it all back together in a way that was brilliant and original and made people think she was extending their ideas.”

Last night I was talking with our mutual friend S, and she said, “I always wanted to hear what Ann would say. She would listen to others present arguments, and then, when it was her turn to speak, she would find the beautiful bits in what she’d heard and put it all back together in a way that was brilliant and original and made people think she was extending their ideas.”

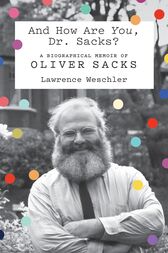

Written by one brilliant writer about another, this remarkable book is, in part, about the craft of writing. But in the main, it’s an account of author Lawrence Weschler’s friendship with Oliver Sacks, a man whom he describes as “impressively erudite and impossibly cuddly.” Sacks comes across as singular. For many years, he lived by himself on City Island, not far from Manhattan, in a house he acquired when he swam out there, saw a house he liked, learned that it was for sale, and bought it that afternoon, his wet trunks dripping in the real estate agent’s office. He regularly swam for miles in the ocean, sometimes late at night. He loved cuttlefish and motorcycles, which he rode, drug-fueled, up and down the California coast when he was a neurology resident at UCLA. A friend of his from that time recalled, “Oliver wouldn’t behave, he wouldn’t follow rules, he’d eat the leftover food off the patients’ trays during rounds, and he drove them nuts.”

Written by one brilliant writer about another, this remarkable book is, in part, about the craft of writing. But in the main, it’s an account of author Lawrence Weschler’s friendship with Oliver Sacks, a man whom he describes as “impressively erudite and impossibly cuddly.” Sacks comes across as singular. For many years, he lived by himself on City Island, not far from Manhattan, in a house he acquired when he swam out there, saw a house he liked, learned that it was for sale, and bought it that afternoon, his wet trunks dripping in the real estate agent’s office. He regularly swam for miles in the ocean, sometimes late at night. He loved cuttlefish and motorcycles, which he rode, drug-fueled, up and down the California coast when he was a neurology resident at UCLA. A friend of his from that time recalled, “Oliver wouldn’t behave, he wouldn’t follow rules, he’d eat the leftover food off the patients’ trays during rounds, and he drove them nuts.” Brexit

Brexit A

A In 1906, Dutch writer Maarten Maartens—acclaimed in his lifetime but now mostly forgotten—published a surreal, satirical novel called The Healers. The book centers on one Professor Lisse, who has conjured up a potential bioweapon: the Semicolon Bacillus, an “especial variety of the Comma.” The doctor has killed hundreds of rabbits demonstrating the Semicolon’s toxicity, but, at the beginning of the novel, he hasn’t yet succeeded in getting his punctuation past the human immune system, which destroys Semicolons instantly as soon as they enter the mouth.

In 1906, Dutch writer Maarten Maartens—acclaimed in his lifetime but now mostly forgotten—published a surreal, satirical novel called The Healers. The book centers on one Professor Lisse, who has conjured up a potential bioweapon: the Semicolon Bacillus, an “especial variety of the Comma.” The doctor has killed hundreds of rabbits demonstrating the Semicolon’s toxicity, but, at the beginning of the novel, he hasn’t yet succeeded in getting his punctuation past the human immune system, which destroys Semicolons instantly as soon as they enter the mouth.