Peter Aldhous in Buzzfeed:

Jeffrey Epstein gave more money to science after his conviction than previously acknowledged, including to famous researchers, leading universities, an independent artificial-intelligence pioneer, and even a far-right YouTuber who took Epstein’s money to make videos on neuroscience.

Jeffrey Epstein gave more money to science after his conviction than previously acknowledged, including to famous researchers, leading universities, an independent artificial-intelligence pioneer, and even a far-right YouTuber who took Epstein’s money to make videos on neuroscience.

An extensive BuzzFeed News review of Epstein’s donations, public acknowledgments of funding, and meetings that happened after his release from jail shows that his links to top scientists continued after he was convicted for sex crimes in 2008.

Epstein’s scientific friends, including Harvard mathematical biologist Martin Nowak and celebrity physicist Lawrence Krauss, introduced him to other leading scientists after his release from jail. The full extent of Epstein’s largesse may be millions of dollars higher than the sums recorded by his foundations in filings to the IRS because Epstein’s philanthropy is entangled with that of his billionaire associate Leon Black.

More here.

Laurie Sheck is a professor of creative writing at the New School in New York, a decades-long veteran of the classroom, a widely published novelist and essayist, and a Pulitzer nominee. She’s also spent the summer in trouble with her bosses for possibly being a racist.

Laurie Sheck is a professor of creative writing at the New School in New York, a decades-long veteran of the classroom, a widely published novelist and essayist, and a Pulitzer nominee. She’s also spent the summer in trouble with her bosses for possibly being a racist. Along with the idea of writing very modern poetry in Yiddish, Vogel also had a specific idea regarding the aesthetics of her work—she wanted the poems to be visual experiences, like paintings. To achieve this effect, instead of relying on the traditional building blocks of poetry which are form and meter, she chose methods derived from painting (mostly cubism), photography (primarily montage) and advertisements (evoking bold colors, catch phrases and kitsch). The most prominent characteristic of the poems in all three collections is repetition. The imagery employed repeats continuously and is used with intention in order to reduce, as Vogel asserted, “the chaos of events to its most basic ordinary properties.”

Along with the idea of writing very modern poetry in Yiddish, Vogel also had a specific idea regarding the aesthetics of her work—she wanted the poems to be visual experiences, like paintings. To achieve this effect, instead of relying on the traditional building blocks of poetry which are form and meter, she chose methods derived from painting (mostly cubism), photography (primarily montage) and advertisements (evoking bold colors, catch phrases and kitsch). The most prominent characteristic of the poems in all three collections is repetition. The imagery employed repeats continuously and is used with intention in order to reduce, as Vogel asserted, “the chaos of events to its most basic ordinary properties.” I wonder what the Rasta-loving Europeans make of Boothe when he appears on stage dressed, typically, to a point beyond distinction, in an evening jacket. ‘But I am a Rasta man,’ he objects, affronted by my ignorance. ‘Look here, what is Rasta? You don’t have to be dreadlocks to be a Rasta. It’s not a fashion; it’s a way of life.’

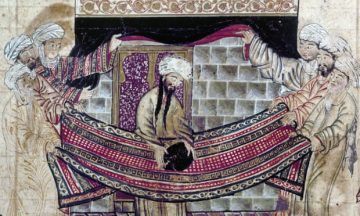

I wonder what the Rasta-loving Europeans make of Boothe when he appears on stage dressed, typically, to a point beyond distinction, in an evening jacket. ‘But I am a Rasta man,’ he objects, affronted by my ignorance. ‘Look here, what is Rasta? You don’t have to be dreadlocks to be a Rasta. It’s not a fashion; it’s a way of life.’ Like many recent years, 2013 saw Richard Dawkins tweet a summary judgment about Islam. “All the world’s Muslims have fewer Nobel prizes than Trinity College, Cambridge. They did great things in the Middle Ages, though.” The coarse implication in his first statement is hardly softened by the condescending allusion to the “great things” done by past Muslims. Still, it was only a tweet. Islamic Empires, Justin Marozzi’s new work, is a 464-page elaboration of the same argument, with additional bloodshed and sleaze.

Like many recent years, 2013 saw Richard Dawkins tweet a summary judgment about Islam. “All the world’s Muslims have fewer Nobel prizes than Trinity College, Cambridge. They did great things in the Middle Ages, though.” The coarse implication in his first statement is hardly softened by the condescending allusion to the “great things” done by past Muslims. Still, it was only a tweet. Islamic Empires, Justin Marozzi’s new work, is a 464-page elaboration of the same argument, with additional bloodshed and sleaze. An ancient face is shedding new light on our earliest ancestors. Archaeologists have discovered a 3.8-million-year-old hominin skull in Ethiopia — a rare and remarkably complete specimen that could change what we know about the origins of one of humanity’s most famous ancestors, Lucy. The researchers who discovered the skull say it belongs to a species called Australopithecus anamensis, and it gives researchers their first good look at the face of this hominin. This species was thought to precede Lucy’s species,Australopithecus afarensis. But features of the latest find now suggest that A. anamensis shared the prehistoric Ethiopian landscape with Lucy’s species, for at least 100,000 years, the researchers say. This hints that the early hominin evolutionary tree was more complicated than scientists had thought — but other researchers say the evidence isn’t yet conclusive.

An ancient face is shedding new light on our earliest ancestors. Archaeologists have discovered a 3.8-million-year-old hominin skull in Ethiopia — a rare and remarkably complete specimen that could change what we know about the origins of one of humanity’s most famous ancestors, Lucy. The researchers who discovered the skull say it belongs to a species called Australopithecus anamensis, and it gives researchers their first good look at the face of this hominin. This species was thought to precede Lucy’s species,Australopithecus afarensis. But features of the latest find now suggest that A. anamensis shared the prehistoric Ethiopian landscape with Lucy’s species, for at least 100,000 years, the researchers say. This hints that the early hominin evolutionary tree was more complicated than scientists had thought — but other researchers say the evidence isn’t yet conclusive. Teaching Augustine’s

Teaching Augustine’s  The emergency department

The emergency department Among the suggestions I would have made to the Yale philosophy professor Jason Stanley had I been an editor of his important book

Among the suggestions I would have made to the Yale philosophy professor Jason Stanley had I been an editor of his important book  The scrapping of Article 370 of the constitution and the dismemberment of the state of Jammu and Kashmir have been much commented upon in recent days. Some commentators have seen these frightening events as rehearsals of what is to come elsewhere in India while others regard them as extensions of state repression in Kashmir and elsewhere in India by all the ruling parties since 1947. The fate of ordinary Kashmiris looks dire and India’s claim to be a democracy is facing its most severe test.

The scrapping of Article 370 of the constitution and the dismemberment of the state of Jammu and Kashmir have been much commented upon in recent days. Some commentators have seen these frightening events as rehearsals of what is to come elsewhere in India while others regard them as extensions of state repression in Kashmir and elsewhere in India by all the ruling parties since 1947. The fate of ordinary Kashmiris looks dire and India’s claim to be a democracy is facing its most severe test. If the experience of my viewing of the film was gently yet insistently altered over the space of two hours, upon its end I experienced a kind of revelation. As I stared at the final image—a still shot of the exterior staircase that Cleo has climbed, itself a return to the opening scene—a thought occurred to me: It is as if I have just seen cinema for the first time.

If the experience of my viewing of the film was gently yet insistently altered over the space of two hours, upon its end I experienced a kind of revelation. As I stared at the final image—a still shot of the exterior staircase that Cleo has climbed, itself a return to the opening scene—a thought occurred to me: It is as if I have just seen cinema for the first time. In

In  For ages, the best ways to treat cancer were surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, but in the last decade doctors have been working to harness patients’ own immune systems to fight cancer. One result is called chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy—CAR T for short—in which doctors remove T cells, which are central to the body’s immune response to disease, and modify them so they’re better prepared to attack cancer cells. CAR T has now been used to treat previously intractable cancers, including certain lymphomas that are the focus of the new study. Yet the treatment only works 30 to 40 percent of the time, said Andrew Rezvani, an assistant professor of medicine who is collaborating on the project. The rest of the time, CAR T’s effectiveness fades away over time or fails altogether.

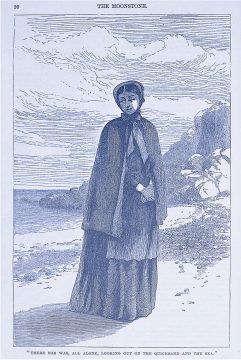

For ages, the best ways to treat cancer were surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, but in the last decade doctors have been working to harness patients’ own immune systems to fight cancer. One result is called chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy—CAR T for short—in which doctors remove T cells, which are central to the body’s immune response to disease, and modify them so they’re better prepared to attack cancer cells. CAR T has now been used to treat previously intractable cancers, including certain lymphomas that are the focus of the new study. Yet the treatment only works 30 to 40 percent of the time, said Andrew Rezvani, an assistant professor of medicine who is collaborating on the project. The rest of the time, CAR T’s effectiveness fades away over time or fails altogether. Like Collins’s earlier The Woman in White, The Moonstone employs a range of sensational plot twists and is narrated by an array of competing voices that variously draw on the reader’s sympathies and skepticism. But where The Woman in White relied on the investigative chops of an art teacher to unravel its mystery, The Moonstone introduces, for the first time in the British novel, the figure of the police investigator: Sergeant Cuff, the character who would set the standard for the new genre of the detective story. Archetypally whimsical and dandyish, Cuff sports a white cravat and a fondness for roses. “One of these days (please God) I shall retire from catching thieves,” he says early on, “and try my hand at growing roses.” Arriving on the scene of the crime, Cuff proceeds to meticulously reconstruct the diamond robbery. His search involves—what else—a close examination of everybody’s closets, “from her ladyship downwards.” No detail is too small to attract his attention, no aspect of domestic life too insignifi cant. Under the impersonal gaze of the detective, no one is beyond suspicion. At one point, Cuff even suspects Rachel of stealing the diamond—from herself. (She didn’t, but what a plot twist that would have been.)

Like Collins’s earlier The Woman in White, The Moonstone employs a range of sensational plot twists and is narrated by an array of competing voices that variously draw on the reader’s sympathies and skepticism. But where The Woman in White relied on the investigative chops of an art teacher to unravel its mystery, The Moonstone introduces, for the first time in the British novel, the figure of the police investigator: Sergeant Cuff, the character who would set the standard for the new genre of the detective story. Archetypally whimsical and dandyish, Cuff sports a white cravat and a fondness for roses. “One of these days (please God) I shall retire from catching thieves,” he says early on, “and try my hand at growing roses.” Arriving on the scene of the crime, Cuff proceeds to meticulously reconstruct the diamond robbery. His search involves—what else—a close examination of everybody’s closets, “from her ladyship downwards.” No detail is too small to attract his attention, no aspect of domestic life too insignifi cant. Under the impersonal gaze of the detective, no one is beyond suspicion. At one point, Cuff even suspects Rachel of stealing the diamond—from herself. (She didn’t, but what a plot twist that would have been.) Quichotte, the Booker Prize long-listed 14th novel from

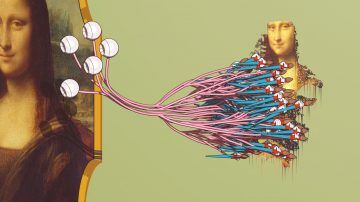

Quichotte, the Booker Prize long-listed 14th novel from  This is the great mystery of human vision: Vivid pictures of the world appear before our mind’s eye, yet the brain’s visual system receives very little information from the world itself. Much of what we “see” we conjure in our heads.

This is the great mystery of human vision: Vivid pictures of the world appear before our mind’s eye, yet the brain’s visual system receives very little information from the world itself. Much of what we “see” we conjure in our heads.