Mitch Anderson in Reasons to be Cheerful:

Like many other nations, Canada is blessed with enormous resource wealth. We are the 7th largest oil-producing nation in the world (Norway is the 15th), with vast forests, mineral deposits and prime farming land. The Canadian province of Alberta legally controls almost 80 percent of the country’s fossil fuel production, has a similar population to Norway yet somehow managed to end up with a $62 billion debt and another $260 billion in unsecured environmental liabilities. Other nations like Nigeria, Venezuela, and Saudi Arabia have become even more wretched examples of resource mismanagement, with deplorable human rights records, dysfunctional economies and rampant graft.

Like many other nations, Canada is blessed with enormous resource wealth. We are the 7th largest oil-producing nation in the world (Norway is the 15th), with vast forests, mineral deposits and prime farming land. The Canadian province of Alberta legally controls almost 80 percent of the country’s fossil fuel production, has a similar population to Norway yet somehow managed to end up with a $62 billion debt and another $260 billion in unsecured environmental liabilities. Other nations like Nigeria, Venezuela, and Saudi Arabia have become even more wretched examples of resource mismanagement, with deplorable human rights records, dysfunctional economies and rampant graft.

Norway is different. Unlike many countries endowed with natural abundance, Norway has somehow avoided the so-called resource curse—where outside interests make off with most of the money and leave behind corrupt and enfeebled institutions.

I had journeyed to Norway to learn how this small country had managed to capture and save over $1 trillion of resource revenue in the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world. Norway regularly tops global rankings on happiness, human rights and the best country to be a mother. They also outright own over half of their oil production, they tax oil profits at close to 80 percent and are still rated as one of the most desirable jurisdictions for international investment.

More here.

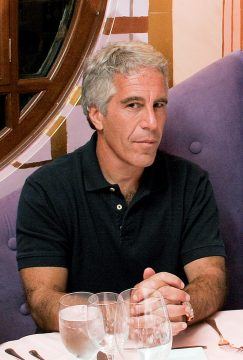

The M.I.T. Media Lab, which has been embroiled in a scandal over accepting donations from the financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, had a deeper fund-raising relationship with Epstein than it has previously acknowledged, and it attempted to conceal the extent of its contacts with him. Dozens of pages of e-mails and other documents obtained by The New Yorker reveal that, although Epstein was listed as “disqualified” in M.I.T.’s official donor database, the Media Lab continued to accept gifts from him, consulted him about the use of the funds, and, by marking his contributions as anonymous, avoided disclosing their full extent, both publicly and within the university. Perhaps most notably, Epstein appeared to serve as an intermediary between the lab and other wealthy donors, soliciting millions of dollars in donations from individuals and organizations, including the technologist and philanthropist Bill Gates and the investor Leon Black. According to the records obtained by The New Yorker and accounts from current and former faculty and staff of the media lab, Epstein was credited with securing at least $7.5 million in donations for the lab, including two million dollars from Gates and $5.5 million from Black, gifts the e-mails describe as “directed” by Epstein or made at his behest. The effort to conceal the lab’s contact with Epstein was so widely known that some staff in the office of the lab’s director, Joi Ito, referred to Epstein as Voldemort or “he who must not be named.”

The M.I.T. Media Lab, which has been embroiled in a scandal over accepting donations from the financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, had a deeper fund-raising relationship with Epstein than it has previously acknowledged, and it attempted to conceal the extent of its contacts with him. Dozens of pages of e-mails and other documents obtained by The New Yorker reveal that, although Epstein was listed as “disqualified” in M.I.T.’s official donor database, the Media Lab continued to accept gifts from him, consulted him about the use of the funds, and, by marking his contributions as anonymous, avoided disclosing their full extent, both publicly and within the university. Perhaps most notably, Epstein appeared to serve as an intermediary between the lab and other wealthy donors, soliciting millions of dollars in donations from individuals and organizations, including the technologist and philanthropist Bill Gates and the investor Leon Black. According to the records obtained by The New Yorker and accounts from current and former faculty and staff of the media lab, Epstein was credited with securing at least $7.5 million in donations for the lab, including two million dollars from Gates and $5.5 million from Black, gifts the e-mails describe as “directed” by Epstein or made at his behest. The effort to conceal the lab’s contact with Epstein was so widely known that some staff in the office of the lab’s director, Joi Ito, referred to Epstein as Voldemort or “he who must not be named.” AS A MEDICAL STUDENT

AS A MEDICAL STUDENT

Ted Mann in Tablet:

Ted Mann in Tablet: Elizabeth Chatterjee in the LRB:

Elizabeth Chatterjee in the LRB: Clive Cookson in the FT:

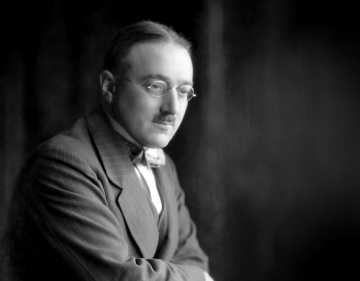

Clive Cookson in the FT: In the 20th century an unfortunate gulf opened up in philosophy between the “continental” and “analytic” schools. Even if you’ve never studied the subject, you might well have heard of this one split. But as the British moral philosopher Bernard Williams once pointed out, the very characterisation of this gulf is odd—one school being characterised by its qualities, the other geographically, like dividing cars between four-wheel drive models and those made in Japan.

In the 20th century an unfortunate gulf opened up in philosophy between the “continental” and “analytic” schools. Even if you’ve never studied the subject, you might well have heard of this one split. But as the British moral philosopher Bernard Williams once pointed out, the very characterisation of this gulf is odd—one school being characterised by its qualities, the other geographically, like dividing cars between four-wheel drive models and those made in Japan.

Charles Wright refused to audition as a hatchet man contestant in the Manhattan token wars in which only one Black writer is left standing during a given era. When I asked George Schuyler, author of the classic novel Black No More, why he, at the time, hadn’t received more recognition, he said he wasn’t a member of The Clique. Tokenism deprives readers of access to a variety of Black writers and smothers the efforts of individual geniuses like Elizabeth Nunez, J. J. Phillips, Charles Wright, and William Demby, whose final novel, King Comus, I published.

Charles Wright refused to audition as a hatchet man contestant in the Manhattan token wars in which only one Black writer is left standing during a given era. When I asked George Schuyler, author of the classic novel Black No More, why he, at the time, hadn’t received more recognition, he said he wasn’t a member of The Clique. Tokenism deprives readers of access to a variety of Black writers and smothers the efforts of individual geniuses like Elizabeth Nunez, J. J. Phillips, Charles Wright, and William Demby, whose final novel, King Comus, I published. One of the most wonderful things about Varda and her camera was the way she circled back, again and again, to previous sites and subjects of her films. Among others, she maintained bonds with the fishermen of La pointe courte, in 2008 performing an anniversary tribute to honor their part in the film. She captured the scene in The Beaches of Agnès, and mutual gratitude hangs in the salt air. Around Demy’s 1990 death from AIDS, Varda not only filmed his childhood memories; she also returned to Rochefort with the cast of a film Demy shot there, making The Young Girls Turn 25 to honor The Young Girls of Rochefort. Through her returns, Varda gave these stories rich new layers. The reciprocal vulnerability between the artist and her subjects extends to viewers when, at the end of Faces Places, we see our bowl cut-rocking cat lady auteur weep in disappointment when Godard isn’t home to receive the pastries she brought him. When has a visionary drawn us in this close?

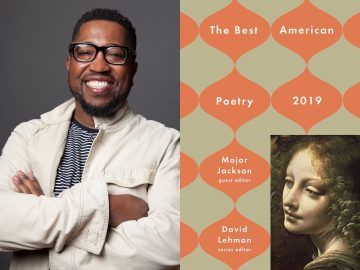

One of the most wonderful things about Varda and her camera was the way she circled back, again and again, to previous sites and subjects of her films. Among others, she maintained bonds with the fishermen of La pointe courte, in 2008 performing an anniversary tribute to honor their part in the film. She captured the scene in The Beaches of Agnès, and mutual gratitude hangs in the salt air. Around Demy’s 1990 death from AIDS, Varda not only filmed his childhood memories; she also returned to Rochefort with the cast of a film Demy shot there, making The Young Girls Turn 25 to honor The Young Girls of Rochefort. Through her returns, Varda gave these stories rich new layers. The reciprocal vulnerability between the artist and her subjects extends to viewers when, at the end of Faces Places, we see our bowl cut-rocking cat lady auteur weep in disappointment when Godard isn’t home to receive the pastries she brought him. When has a visionary drawn us in this close? Poems have reacquainted me with the spectacular spirit of the human, that which is fundamentally elusive to algorithms, artificial intelligence, behavioral science, and genetic research: “Sometimes I get up early and even my soul is wet” (Pablo Neruda, “Here I Love You”); “Earth’s the right place for love: / I don’t know where it’s likely to go better” (Robert Frost, “Birches”); “I wonder what death tastes like. / Sometimes I toss the butterflies / Back into the air” (Yusef Komunyakaa, “Venus’s Flytrap”); “The world / is flux, and light becomes what it touches” (Lisel Mueller, “Monet Refuses the Operation”); “We do not want them to have less. / But it is only natural that we should think we have not enough” (Gwendolyn Brooks, “Beverly Hills, Chicago”). Once, while in graduate school, reading Wordsworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” in the corner of a café, I was surprised to find myself with brimming eyes, filled with unspeakable wonder and sadness at the veracity of his words: “Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting: / The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star, / Hath had elsewhere its setting, / And cometh from afar.” Poetry, as the poet Edward Hirsch has written, “speaks out of a solitude to a solitude.”

Poems have reacquainted me with the spectacular spirit of the human, that which is fundamentally elusive to algorithms, artificial intelligence, behavioral science, and genetic research: “Sometimes I get up early and even my soul is wet” (Pablo Neruda, “Here I Love You”); “Earth’s the right place for love: / I don’t know where it’s likely to go better” (Robert Frost, “Birches”); “I wonder what death tastes like. / Sometimes I toss the butterflies / Back into the air” (Yusef Komunyakaa, “Venus’s Flytrap”); “The world / is flux, and light becomes what it touches” (Lisel Mueller, “Monet Refuses the Operation”); “We do not want them to have less. / But it is only natural that we should think we have not enough” (Gwendolyn Brooks, “Beverly Hills, Chicago”). Once, while in graduate school, reading Wordsworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” in the corner of a café, I was surprised to find myself with brimming eyes, filled with unspeakable wonder and sadness at the veracity of his words: “Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting: / The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star, / Hath had elsewhere its setting, / And cometh from afar.” Poetry, as the poet Edward Hirsch has written, “speaks out of a solitude to a solitude.” The climate of South Asia is not kind to ancient DNA. It is hot and it rains. In monsoon season, water seeps into ancient bones in the ground, degrading the old genetic material. So by the time archeologists and geneticists finally got DNA out of a tiny ear bone from a 4,000-plus-year-old skeleton, they had already tried dozens of samples—all from cemeteries of the mysterious Indus Valley civilization, all without any success. The Indus Valley civilization, also known as the Harappan civilization, flourished 4,000 years ago in what is now India and Pakistan. It surpassed its contemporaries, Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, in size. Its trade routes stretched thousands of miles. It had agriculture and planned cities and sewage systems. And then, it disappeared. “The Indus Valley civilization has been an enigma for South Asians. We read about it in our textbooks,” says

The climate of South Asia is not kind to ancient DNA. It is hot and it rains. In monsoon season, water seeps into ancient bones in the ground, degrading the old genetic material. So by the time archeologists and geneticists finally got DNA out of a tiny ear bone from a 4,000-plus-year-old skeleton, they had already tried dozens of samples—all from cemeteries of the mysterious Indus Valley civilization, all without any success. The Indus Valley civilization, also known as the Harappan civilization, flourished 4,000 years ago in what is now India and Pakistan. It surpassed its contemporaries, Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, in size. Its trade routes stretched thousands of miles. It had agriculture and planned cities and sewage systems. And then, it disappeared. “The Indus Valley civilization has been an enigma for South Asians. We read about it in our textbooks,” says  Over the past two centuries, millions of dedicated people – revolutionaries, activists, politicians, and theorists – have yet to curb the disastrous and increasingly globalised trajectory of economic polarisation and ecological degradation. Perhaps because we are utterly trapped in flawed ways of thinking about technology and economy – as the current discourse on climate change shows. Rising greenhouse gas emissions are not just generating climate change. They are giving more and more of us climate anxiety –

Over the past two centuries, millions of dedicated people – revolutionaries, activists, politicians, and theorists – have yet to curb the disastrous and increasingly globalised trajectory of economic polarisation and ecological degradation. Perhaps because we are utterly trapped in flawed ways of thinking about technology and economy – as the current discourse on climate change shows. Rising greenhouse gas emissions are not just generating climate change. They are giving more and more of us climate anxiety –

“Correlation is not causation.”

“Correlation is not causation.”