Suketu Mehta in Scroll.in:

These days, a great many people in the rich countries complain loudly about migration from the poor ones. But the game was rigged: First, the rich countries colonised us and stole our treasure and prevented us from building our industries. After plundering us for centuries, they left, having drawn up maps in ways that ensured permanent strife between our communities. Then they brought us to their countries as “guest workers” – as if they knew what the word “guest” meant in our cultures – but discouraged us from bringing our families.

These days, a great many people in the rich countries complain loudly about migration from the poor ones. But the game was rigged: First, the rich countries colonised us and stole our treasure and prevented us from building our industries. After plundering us for centuries, they left, having drawn up maps in ways that ensured permanent strife between our communities. Then they brought us to their countries as “guest workers” – as if they knew what the word “guest” meant in our cultures – but discouraged us from bringing our families.

Having built up their economies with our raw materials and our labour, they asked us to go back and were surprised when we did not. They stole our minerals and corrupted our governments so that their corporations could continue stealing our resources; they fouled the air above us and the waters around us, making our farms barren, our oceans lifeless; and they were aghast when the poorest among us arrived at their borders, not to steal but to work, to clean their shit, and to sleep with their men.

Still, they needed us. They needed us to fix their computers and heal their sick and teach their kids, so they took our best and brightest, those who had been educated at the greatest expense of the struggling states they came from, and seduced us again to work for them. Now, again they ask us not to come, desperate and starving though they have rendered us, because the richest among them need a scapegoat. This is how the game is rigged today.

More here.

I cannot think of a contemporary piece that has attracted as much of a cult following as Haas’s mesmerizing, disorienting, and utterly moving in vain. It begins with a swirl of sound in which the cascading runs suggest a sense of falling, yet as these lines rise in pitch, there’s a feeling of upward motion, too—the musical equivalent, as many commentators have noted, of M. C. Escher’s staircase, descending and ascending all at once. Soon after a hair-raising crescendo, the listener is plunged into another realm, in which microtonality seems at war with conventional tuning. The sounds pulse like flashes of light through an abiding darkness, which is not only metaphorical but also literal, for in a live performance, the house lights gradually dim and are then cut. (Unable to see either their music stands or the conductor, the performers must play extended sequences of very complex music from memory.) Out of this darkness, a new world of sound emerges, something elemental—familiar but strange—with the textures and harmonies undergoing subtle transformations. Just when it seems as if some redemptive moment will arrive, the music becomes frustratingly dizzying once again. Indeed, listening to in vain can feel like being trapped in an anxiety dream from which you almost manage to escape, but ultimately cannot.

I cannot think of a contemporary piece that has attracted as much of a cult following as Haas’s mesmerizing, disorienting, and utterly moving in vain. It begins with a swirl of sound in which the cascading runs suggest a sense of falling, yet as these lines rise in pitch, there’s a feeling of upward motion, too—the musical equivalent, as many commentators have noted, of M. C. Escher’s staircase, descending and ascending all at once. Soon after a hair-raising crescendo, the listener is plunged into another realm, in which microtonality seems at war with conventional tuning. The sounds pulse like flashes of light through an abiding darkness, which is not only metaphorical but also literal, for in a live performance, the house lights gradually dim and are then cut. (Unable to see either their music stands or the conductor, the performers must play extended sequences of very complex music from memory.) Out of this darkness, a new world of sound emerges, something elemental—familiar but strange—with the textures and harmonies undergoing subtle transformations. Just when it seems as if some redemptive moment will arrive, the music becomes frustratingly dizzying once again. Indeed, listening to in vain can feel like being trapped in an anxiety dream from which you almost manage to escape, but ultimately cannot. Stubbs was, however, an interpreter as well as an observer. His pictures reveal his fascination with relationships; between owners and their horses and hounds, between servants and masters, between animals themselves. And they show his very modern conviction that animals have emotions similar to and every bit as potent as our own. The eyes of his creatures are full of feeling and frequently stare back at the viewer with disconcerting intensity. You need only to look at the eye of his horse being devoured by a lion, a motif he returned to again and again, to be made uncomfortable as a witness to its agony. In a remarkable late work of 1800 showing the Earl of Clarendon’s gamekeeper with his dog about to dispatch a doe, man and doomed animal look out of the painting, making the viewer complicit in the coup de grâce. Other near contemporaries such as James Ward and Théodore Géricault gave their animals emotions, but without the same fellow feeling.

Stubbs was, however, an interpreter as well as an observer. His pictures reveal his fascination with relationships; between owners and their horses and hounds, between servants and masters, between animals themselves. And they show his very modern conviction that animals have emotions similar to and every bit as potent as our own. The eyes of his creatures are full of feeling and frequently stare back at the viewer with disconcerting intensity. You need only to look at the eye of his horse being devoured by a lion, a motif he returned to again and again, to be made uncomfortable as a witness to its agony. In a remarkable late work of 1800 showing the Earl of Clarendon’s gamekeeper with his dog about to dispatch a doe, man and doomed animal look out of the painting, making the viewer complicit in the coup de grâce. Other near contemporaries such as James Ward and Théodore Géricault gave their animals emotions, but without the same fellow feeling. Krasznahorkai is a perplexing figure in today’s literary landscape: he is, in internet parlance, committed to his bit. The Hungarian author cultivates an air of mystery (he “lives in reclusiveness,” according to one

Krasznahorkai is a perplexing figure in today’s literary landscape: he is, in internet parlance, committed to his bit. The Hungarian author cultivates an air of mystery (he “lives in reclusiveness,” according to one  There were ideas long before there were light bulbs. But, of all the ideas that have ever turned into inventions, only the light bulb became a symbol of ideas. Earlier innovations had literalized the experience of “seeing the light,” but no one went around talking about torchlight moments or sketching candles into cartoon thought bubbles. What made the light bulb such an irresistible image for ideas was not just the invention but its inventor.

There were ideas long before there were light bulbs. But, of all the ideas that have ever turned into inventions, only the light bulb became a symbol of ideas. Earlier innovations had literalized the experience of “seeing the light,” but no one went around talking about torchlight moments or sketching candles into cartoon thought bubbles. What made the light bulb such an irresistible image for ideas was not just the invention but its inventor. In 2014, when Ian Miller and Tyler Lyson first visited Corral Bluffs, a fossil site 100 kilometers south of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science where they work, Lyson was not impressed by the few vertebrate fossils he saw. But on a return trip later that year, he split open small boulders called concretions—and found dozens of skulls. Now, he, Miller, and their colleagues have combined the site’s trove of plant and animal fossils with a detailed chronology of the rock layers to tell a momentous story: how life recovered from the asteroid impact that killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

In 2014, when Ian Miller and Tyler Lyson first visited Corral Bluffs, a fossil site 100 kilometers south of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science where they work, Lyson was not impressed by the few vertebrate fossils he saw. But on a return trip later that year, he split open small boulders called concretions—and found dozens of skulls. Now, he, Miller, and their colleagues have combined the site’s trove of plant and animal fossils with a detailed chronology of the rock layers to tell a momentous story: how life recovered from the asteroid impact that killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Last April, Princeton University economists and married partners

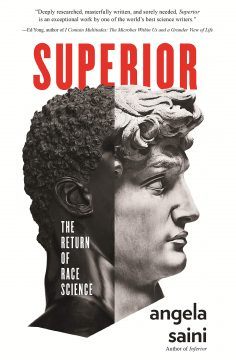

Last April, Princeton University economists and married partners  A dozen years ago I flew to Europe to speak at a conference on science’s limits. The meeting’s organizer greeted me with a tirade about James Watson, co-discoverer of the double helix, who had just stated publicly that blacks are less intelligent than whites. “All our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours,”

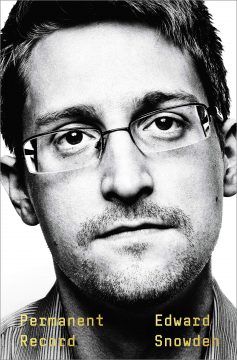

A dozen years ago I flew to Europe to speak at a conference on science’s limits. The meeting’s organizer greeted me with a tirade about James Watson, co-discoverer of the double helix, who had just stated publicly that blacks are less intelligent than whites. “All our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours,”  Edward Snowden, late in the pages of his memoir, Permanent Record, describes his sensation at being personally introduced to XKEYSCORE, the NSA’s ultimate tool of intimate, individual electronic surveillance. Among the NSA’s technological tools (some of which Snowden aided in perfecting), XKEYSCORE was, according to Snowden, “the most invasive…if only because [the NSA agents are] closest to the user—that is, the closest to the person being surveilled.” For nearly three hundred pages, the memoir has built to this scene, foreshadowed in the preface, in which the whistleblower-in-the-making sees behind the curtain:

Edward Snowden, late in the pages of his memoir, Permanent Record, describes his sensation at being personally introduced to XKEYSCORE, the NSA’s ultimate tool of intimate, individual electronic surveillance. Among the NSA’s technological tools (some of which Snowden aided in perfecting), XKEYSCORE was, according to Snowden, “the most invasive…if only because [the NSA agents are] closest to the user—that is, the closest to the person being surveilled.” For nearly three hundred pages, the memoir has built to this scene, foreshadowed in the preface, in which the whistleblower-in-the-making sees behind the curtain: What is smoking for? People who don’t smoke think it’s for feeding an addiction, and they’re right. Once you’ve started smoking, it’s hard to stop. But that’s a narrow definition. There’s a physical addiction and there’s also a spiritual addiction. Perhaps you could call it a metaphysical addiction.

What is smoking for? People who don’t smoke think it’s for feeding an addiction, and they’re right. Once you’ve started smoking, it’s hard to stop. But that’s a narrow definition. There’s a physical addiction and there’s also a spiritual addiction. Perhaps you could call it a metaphysical addiction. Apart from his short video outing himself in 2013, Snowden has tended to keep himself out of the public eye, preferring that the material speak for itself. He is, in many respects, the opposite of Julian Assange – a figure with whom he is often bracketed. The founder of WikiLeaks wanted to be a player: impresario, editor, publisher, activist, leaker, information anarchist and troublemaker. Snowden, by contrast, simply wanted to get his documents into the hands of journalists, and to leave them to make the choices about what to publish.

Apart from his short video outing himself in 2013, Snowden has tended to keep himself out of the public eye, preferring that the material speak for itself. He is, in many respects, the opposite of Julian Assange – a figure with whom he is often bracketed. The founder of WikiLeaks wanted to be a player: impresario, editor, publisher, activist, leaker, information anarchist and troublemaker. Snowden, by contrast, simply wanted to get his documents into the hands of journalists, and to leave them to make the choices about what to publish. Around

Around  Simon draws attention to “the extreme ambivalence we now feel towards beauty both within and outside art,” and continues: “We distrust it; we fear its power; we associate it with compulsion and uncontrollable desire of a sexual fetish. Embarrassed by our yearning for beauty, we demean it as something tawdry, self-indulgent, or sentimental.”

Simon draws attention to “the extreme ambivalence we now feel towards beauty both within and outside art,” and continues: “We distrust it; we fear its power; we associate it with compulsion and uncontrollable desire of a sexual fetish. Embarrassed by our yearning for beauty, we demean it as something tawdry, self-indulgent, or sentimental.” It all began with a book review. Last year, I read

It all began with a book review. Last year, I read  A

A  The

The