Aaron Kheriaty in The Scientist:

On June 9, 2016, a law permitting physician-assisted suicide went into effect in California. The same day, Dr. Lonny Shavelson, an emergency medicine physician, opened the Bay Area End of Life Options clinic to provide the newly legal service. A longtime activist for the cause, Shavelson’s interest began in adolescence. In an interview last year, he describes how, when he was fourteen, his severely depressed mother “enrolled me in pacts for her death.” Despite acknowledging that her request was “pathological,” he eventually chose to become a doctor “not only to help her in her illness but also to help her die.” In his 1995 book A Chosen Death, Shavelson recounted underground assisted suicides he witnessed. In one case, “Sarah,” the leader of a local advocacy group, took an especially active role when “Gene,” an elderly, partially paralyzed alcoholic man, asked for help with ending his life. But things did not go as planned, when Gene jolted awake in the middle of the process:

On June 9, 2016, a law permitting physician-assisted suicide went into effect in California. The same day, Dr. Lonny Shavelson, an emergency medicine physician, opened the Bay Area End of Life Options clinic to provide the newly legal service. A longtime activist for the cause, Shavelson’s interest began in adolescence. In an interview last year, he describes how, when he was fourteen, his severely depressed mother “enrolled me in pacts for her death.” Despite acknowledging that her request was “pathological,” he eventually chose to become a doctor “not only to help her in her illness but also to help her die.” In his 1995 book A Chosen Death, Shavelson recounted underground assisted suicides he witnessed. In one case, “Sarah,” the leader of a local advocacy group, took an especially active role when “Gene,” an elderly, partially paralyzed alcoholic man, asked for help with ending his life. But things did not go as planned, when Gene jolted awake in the middle of the process:

“It’s cold,” he screamed, and his good hand flew up to tear off the plastic bag. Sarah’s hand caught Gene’s at the wrist and held it. His body thrust upwards. She pulled his arm away and lay across Gene’s shoulders. Sarah rocked back and forth, pinning him down, her fingers twisting the bag to seal it tight at his neck as she repeated, “The light, Gene, go toward the light.” Gene’s body pushed against Sarah’s. Then he stopped moving.

Shavelson watched, frozen with ambivalence at whether to intervene. He did not.

Shavelson seems to have taken away from this event a sense of the dire need for reliable methods for ending life. Ignorance of these methods, he argued in last year’s interview, was much of what motivated doctors to oppose assisted suicide:

Everybody I talked to said we don’t know how to do this. So we don’t agree with it. And over time, what’s wonderful to watch is how patients have been the leading force…. As [hospices] started getting patient requests, they couldn’t just keep saying no. Hospices are fundamentally a loving and caring and responsive organization.

He and his colleagues have thus made themselves “ambassadors,” training physicians around the state on proper suicide methods to meet patient demand. As of last November, Dr. Shavelson and his staff had been at the bedside of 114 people whose suicides they assisted.

More here.

I have recently been informed that I am “outside of the sociology” of academic philosophy. (The person who said this of me is someone I like and admire, and whose presence on the scene I value, very much.) I think this means, for one thing, that I do not display a number of the shibboleths that are commonly used by members of the clan to identify other members, like Vikings with their brooches. Sometimes this is because I refuse to display them, and sometimes this is because I am unaware that they exist.

I have recently been informed that I am “outside of the sociology” of academic philosophy. (The person who said this of me is someone I like and admire, and whose presence on the scene I value, very much.) I think this means, for one thing, that I do not display a number of the shibboleths that are commonly used by members of the clan to identify other members, like Vikings with their brooches. Sometimes this is because I refuse to display them, and sometimes this is because I am unaware that they exist. The technique, officially called emergency preservation and resuscitation (EPR), is being carried out on people who arrive at the University of Maryland Medical Centre in Baltimore with an acute trauma – such as a gunshot or stab wound – and have had a cardiac arrest. Their heart will have stopped beating and they will have lost more than half their blood. There are only minutes to operate, with a less than 5 per cent chance that they would normally survive.

The technique, officially called emergency preservation and resuscitation (EPR), is being carried out on people who arrive at the University of Maryland Medical Centre in Baltimore with an acute trauma – such as a gunshot or stab wound – and have had a cardiac arrest. Their heart will have stopped beating and they will have lost more than half their blood. There are only minutes to operate, with a less than 5 per cent chance that they would normally survive. In India today, a shadow world is creeping up on us in broad daylight. It is becoming more and more difficult to communicate the scale of the crisis even to ourselves. An accurate description runs the risk of sounding like hyperbole. And so, for the sake of credibility and good manners, we groom the creature that has sunk its teeth into us—we comb out its hair and wipe its dripping jaw to make it more personable in polite company. India isn’t by any means the worst, or most dangerous, place in the world—at least not yet—but perhaps the divergence between what it could have been and what it has become makes it the most tragic.

In India today, a shadow world is creeping up on us in broad daylight. It is becoming more and more difficult to communicate the scale of the crisis even to ourselves. An accurate description runs the risk of sounding like hyperbole. And so, for the sake of credibility and good manners, we groom the creature that has sunk its teeth into us—we comb out its hair and wipe its dripping jaw to make it more personable in polite company. India isn’t by any means the worst, or most dangerous, place in the world—at least not yet—but perhaps the divergence between what it could have been and what it has become makes it the most tragic. Hiroshima ran to 31,000 words. The original article filled the entire edition of the New Yorker on 31 August 1946, the first time in the magazine’s history that this had ever happened. It was serialised in full in eighty other publications around the world and eventually even in Japan. Subsequently republished in book form, it has been in print ever since and has sold more than three million copies. And yet, unusually for a work of journalism, it appeared more than a year after the events it described. There were reasons for the delay. One was the difficulty of accessing Hiroshima and the severity of postwar censorship. Another was the effect of the demonisation of the Japanese people in the American media after the attack on Pearl Harbor. It took an original mind and an eloquent pen to portray them as victims as well as aggressors. Hersey possessed both. Among his peers, in my view, he was rivalled only by the late and great James Cameron of the equally late and great News Chronicle.

Hiroshima ran to 31,000 words. The original article filled the entire edition of the New Yorker on 31 August 1946, the first time in the magazine’s history that this had ever happened. It was serialised in full in eighty other publications around the world and eventually even in Japan. Subsequently republished in book form, it has been in print ever since and has sold more than three million copies. And yet, unusually for a work of journalism, it appeared more than a year after the events it described. There were reasons for the delay. One was the difficulty of accessing Hiroshima and the severity of postwar censorship. Another was the effect of the demonisation of the Japanese people in the American media after the attack on Pearl Harbor. It took an original mind and an eloquent pen to portray them as victims as well as aggressors. Hersey possessed both. Among his peers, in my view, he was rivalled only by the late and great James Cameron of the equally late and great News Chronicle. Few composers—in his time and in the centuries since—have been as deft as Purcell at marrying text and sound. His opera Dido and Aeneas is a seminal work, the most important of his compositions for the stage, and his songs, of which he wrote more than 100, are exemplary (such 20th-century English composers as Benjamin Britten and Michael Tippett would pay brilliant homage to them in their own ways). Between 1692 and 1695, Purcell composed three settings of Colonel Heveningham’s poem, all of them beautiful. The first two are more or less similar, but the third is a different work altogether, more florid, more darkly evocative.

Few composers—in his time and in the centuries since—have been as deft as Purcell at marrying text and sound. His opera Dido and Aeneas is a seminal work, the most important of his compositions for the stage, and his songs, of which he wrote more than 100, are exemplary (such 20th-century English composers as Benjamin Britten and Michael Tippett would pay brilliant homage to them in their own ways). Between 1692 and 1695, Purcell composed three settings of Colonel Heveningham’s poem, all of them beautiful. The first two are more or less similar, but the third is a different work altogether, more florid, more darkly evocative. Revising One Sentence” is the title of one of the essays in Lydia Davis’s masterful, lucid collection. No single piece could capture the essence of this extraordinary writer, but a new reader might wish to start here. This is the sentence in question, in its final version: “She walks around the house balancing on the balls of her feet, sometimes whistling and singing, sometimes talking to herself, sometimes stopping dead in a fencing position.” Nothing to see here, you might think. But think again.

Revising One Sentence” is the title of one of the essays in Lydia Davis’s masterful, lucid collection. No single piece could capture the essence of this extraordinary writer, but a new reader might wish to start here. This is the sentence in question, in its final version: “She walks around the house balancing on the balls of her feet, sometimes whistling and singing, sometimes talking to herself, sometimes stopping dead in a fencing position.” Nothing to see here, you might think. But think again. In 1940, Ernest Hemingway wrote of the Spanish Civil War and the Guadarrama Mountains of Spain: “The Guadarrama Mountains of Spain run from northeast to southwest across the central plains of Castille. They are ancient mountains, formed of pale granite and gneiss, their slopes densely wooded with pines of several species: black pines, maritime pines, sentry pines, Scots pines. To visit them is to be able to recall the scents of those days and nights, even years on: ‘the piney smell of … crushed needles’, as Ernest Hemingway puts it in for Whom the Bell Tolls, ‘and the sharper odour of … resinous sap’.

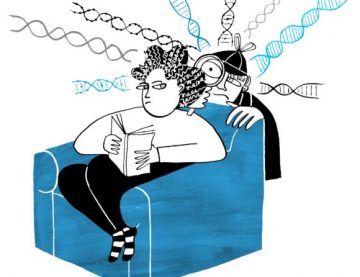

In 1940, Ernest Hemingway wrote of the Spanish Civil War and the Guadarrama Mountains of Spain: “The Guadarrama Mountains of Spain run from northeast to southwest across the central plains of Castille. They are ancient mountains, formed of pale granite and gneiss, their slopes densely wooded with pines of several species: black pines, maritime pines, sentry pines, Scots pines. To visit them is to be able to recall the scents of those days and nights, even years on: ‘the piney smell of … crushed needles’, as Ernest Hemingway puts it in for Whom the Bell Tolls, ‘and the sharper odour of … resinous sap’. Scientists have come up with a drug, injected once a day, that appears to make children’s bones grow. To many, it’s a wondrous invention that could improve the lives of thousands of people with dwarfism. To others, it’s a profit-driven solution in search of a problem, one that could unravel decades of hard-won respect for an entire community. In the middle are families, doctors, and a pharmaceutical company, all dealing with a philosophically fraught question: Is it ethical to make a little person taller? The most common cause of dwarfism is known as achondroplasia. People with the condition, caused by a rare genetic mutation, have shorter limbs and shorter stature than those without it, and they deal with a lifetime of skeletal issues that often require a battery of corrective surgeries.

Scientists have come up with a drug, injected once a day, that appears to make children’s bones grow. To many, it’s a wondrous invention that could improve the lives of thousands of people with dwarfism. To others, it’s a profit-driven solution in search of a problem, one that could unravel decades of hard-won respect for an entire community. In the middle are families, doctors, and a pharmaceutical company, all dealing with a philosophically fraught question: Is it ethical to make a little person taller? The most common cause of dwarfism is known as achondroplasia. People with the condition, caused by a rare genetic mutation, have shorter limbs and shorter stature than those without it, and they deal with a lifetime of skeletal issues that often require a battery of corrective surgeries. The opposite of the jerk is the sweetheart. The sweetheart sees others around him, even strangers, as individually distinctive people with valuable perspectives, whose desires and opinions, interests and goals, are worthy of attention and respect. The sweetheart yields his place in line to the hurried shopper, stops to help the person who has dropped her papers, calls an acquaintance with an embarrassed apology after having been unintentionally rude. In a debate, the sweetheart sees how he might be wrong and the other person right.

The opposite of the jerk is the sweetheart. The sweetheart sees others around him, even strangers, as individually distinctive people with valuable perspectives, whose desires and opinions, interests and goals, are worthy of attention and respect. The sweetheart yields his place in line to the hurried shopper, stops to help the person who has dropped her papers, calls an acquaintance with an embarrassed apology after having been unintentionally rude. In a debate, the sweetheart sees how he might be wrong and the other person right. Like cosmic hard drives, black holes pack troves of data into compact spaces. But ever since Stephen Hawking

Like cosmic hard drives, black holes pack troves of data into compact spaces. But ever since Stephen Hawking  At his first official press conference in 2017, Press Secretary Sean Spicer made a telling choice. After giving the first question to the New York Post, he then called on Jennifer Wishon, who was sitting at the back, in the seventh row. He didn’t mention the news organization she represented, but it was no secret: since 2011 she had served as the White House correspondent for the Christian Broadcasting Network.

At his first official press conference in 2017, Press Secretary Sean Spicer made a telling choice. After giving the first question to the New York Post, he then called on Jennifer Wishon, who was sitting at the back, in the seventh row. He didn’t mention the news organization she represented, but it was no secret: since 2011 she had served as the White House correspondent for the Christian Broadcasting Network. Vladimir Nabokov and D. H. Lawrence each wrote a major novel (“Lolita,” “Lady Chatterley’s Lover”) that was banned and unbanned and banned again before being cut free.

Vladimir Nabokov and D. H. Lawrence each wrote a major novel (“Lolita,” “Lady Chatterley’s Lover”) that was banned and unbanned and banned again before being cut free. As a story-loving child more likely to be found playing detectives than the now-suspect doctors and nurses, I yearned for a family secret. My parents had both been raised with them: in my mother’s case, her dad’s Jewishness was kept hidden from her; in my father’s, paternity remained an unsolved mystery (Pétainist French Catholic priest or local milkman?).

As a story-loving child more likely to be found playing detectives than the now-suspect doctors and nurses, I yearned for a family secret. My parents had both been raised with them: in my mother’s case, her dad’s Jewishness was kept hidden from her; in my father’s, paternity remained an unsolved mystery (Pétainist French Catholic priest or local milkman?). To riff on the opening lines of Steven Shapin’s

To riff on the opening lines of Steven Shapin’s